Last month, editors of The Youngstown Vindicator, one of Ohio’s most respected newspapers, made an unusual appeal on their op-ed page. They asked the state superintendent of public instruction, Richard Ross, to take over their local school system.

The Youngstown Board of Education had, in their opinion, “failed to provide the needed leadership to prevent the academic meltdown” occurring in their district. They added that Mr. Ross was “overly optimistic” in believing that the community could come together to develop a plan to save the district. Therefore, they pleaded, “[W]e urge state Superintendent Ross to assign the task of restructuring the Youngstown school system to his staff and not wait for community consensus.”

It’s not every day that local citizens ask the state to take charge of educating the children in their community. Such a move illustrates the despair that many Americans feel about their own schools—and their inability to do much to improve them.

That’s why, over three years ago, we at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, along with our friends at the Center for American Progress, began a multi-year initiative designed to draw attention to the elephant in the ed-reform living room: governance. Given its ability to trample any promising education improvement—or clear the way for its implementation—it was high time to put governance at center stage of the policy conversation.

Our “anchor book” for that initiative, Education Governance for the Twenty-First Century: Overcoming the Structural Barriers to School Reform (January 2013), demonstrated how our highly fragmented, politicized, and bureaucratic system of education governance impeded school reform. One promising innovation it identified was the “recovery school district” (RSD)—an alternative to district-based governance that became a household name after Hurricane Katrina pummeled New Orleans. As new state-created entities charged with running and turning around the state’s worst schools, these districts are awarded certain authority and flexibility—such as the ability to turn schools into charters and to bypass collective bargaining agreements—that allow them to cut the red tape that has made so many schools dysfunctional in the first place.

Tennessee policymakers took note of the RSD’s success and in 2011 created the Achievement School District. Yet, outside of the Volunteer State, these alternative models have been met by policymakers and educators with way more resistance than welcome. By our count, recovery districts have been pushed in at least seven states since 2011; few have seen the light of day.

Last winter in Mississippi, house and senate bills establishing an “achievement school district” both died. The same thing happened last spring with a house bill in Texas (though gubernatorial hopeful Greg Abbott is now attempting to resuscitate it in his education platform). This summer, a Virginia circuit court judge ruled that statewide turnaround districts were unconstitutional in that state. More recently, in Georgia, Governor Nathan Deal urged lawmakers to “consider” the Louisiana model as one way to improve failing schools (it has yet to gain momentum). Likewise, officials in New Jersey and Wisconsin have toyed with the idea of statewide districts, but nothing more.

Why is it so hard for these new arrangements to gain traction? Opponents tend to complain that the districts divert funding from public schools (forgetting that they are still public) and that they remove control of schools from local oversight, handing them to state authorities and even (gasp) charter school operators.

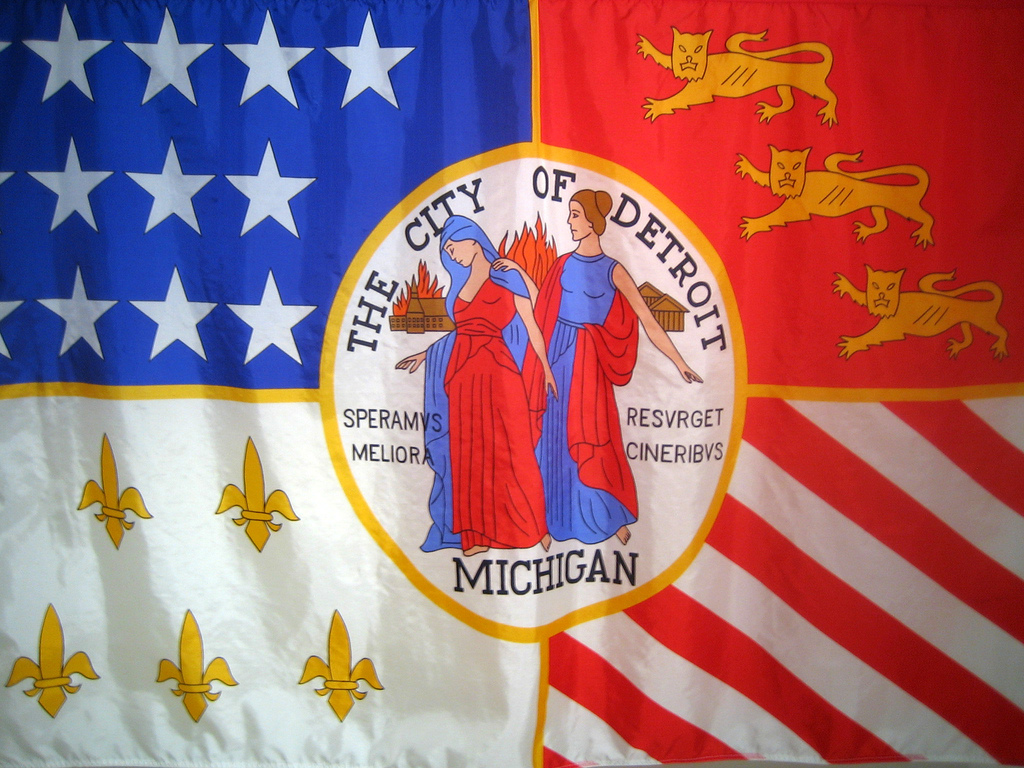

Enter the Education Achievement Authority (EAA) in Michigan. It shares basic similarities with its brethren in Louisiana and Tennessee in that all three are charged with resuscitating the state’s worst schools within the confines of a separate, autonomous district.

But unlike the RSD in the Bayou State—which has over eighty schools statewide—the EAA is so far a more modest effort, responsible for just fifteen schools, all in Detroit, with further expansion stymied. Like the Achievement School District (ASD) in the Volunteer State, the EAA was created in response to the Race to the Top competition. Yet it is an interesting hybrid of both existing models: it combines the governance reforms of the RSD and ASD with a big push for competency-based, blended learning. And that’s what has made news: tech-oriented bloggers are singing the praises of the daring new learning platform the Authority developed, while those opposed to the whole idea of the EAA are lamenting that its students are being used as guinea pigs for market-greedy entrepreneurs.

This makes for good melodrama, but really, what are the takeaways of the EAA for other districts? To find out, we enlisted Nelson Smith, former head of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, who is now senior advisor to the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA). Nelson has also held senior positions at the U. S. Department of Education, the D.C. Public Charter School Board, and New American Schools. He’s keenly aware of the challenges in forging alternative educational options for kids—and in implementing recovery districts, particularly after having authored insightful reports for us on such efforts in Tennessee and Louisiana.

The EAA model—direct-run schools with limited reliance on chartering and a high-tech approach—is far from the catastrophe that some critics claim. Yet the critics aren’t all wrong. There have been many hurdles, and there is some validity to both the EAA’s claims of progress and the criticism that early results are disappointing. Some students don’t respond well to the online component or can’t handle the autonomy they’re given over their own learning. An instructional cocktail for low-achieving students that mixes competency-based, blended, and student-centered learning is tricky—and doesn’t work for all students.

In the end, the EAA was rolled out on a tight timeline. On a shoestring budget. Amid urban decline in Detroit. It would have taken a miracle for this to work out well. (Which is something policymakers might have considered before pursuing this path.) Further, its governance arrangement is a Rube Goldberg invention of epic proportions.

What’s more, officials needed adequate charter funding to woo high-quality operators to the Motor City. They didn’t have it—and they didn’t get them. And the inaugural superintendent of the EAA, John Covington, has since stepped down amid news of enrollment declines, budget woes, and other challenges.

Still, the EAA is not the complete disaster you may have heard it to be. But it’s also not a success like the RSD or ASD—both of which are improving outcomes, albeit slowly, for kids.

Which might make its cautionary lessons that much more important for other states thinking of going down this route.

The key takeaway is that neither statewide school districts nor blended, competency-based learning are silver bullets. Combining the two is a particularly precarious proposition. Furthermore, states that want to embrace this approach to school turnarounds need to create conditions that are essential to success. Michigan’s effort—though laudable, and in many ways heroic—was hobbled from the start from too many compromises and too little political support.

As with most reforms—think charter schools, or teacher evaluations—this strategy is only worth doing if done well. When it comes to educational improvement, half measures and work-arounds are rarely enough.

photo credit: erikadotnet via photopin cc