Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2022 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can states remove policies barriers that are keeping educators from reinventing high schools?” Learn more.

Imagine if, by fourteen or fifteen years old, you’d sat down with a counselor who could not only teach you about high-paying, high-demand careers in your area, but connect you with real opportunities to try them out. If you were supported in setting a graduation plan based on your career interests and then guided toward classes, credentials, and hands-on training accordingly. Imagine heading off to college or the workforce having not only studied math, English, and social studies, but also apprenticed under a local electrician, earned a pharmacy tech credential, or taken engineering classes while interning at Google.

Of course, that’s not the experience for the vast majority of high school students in the United States. Despite nearly half a century dedicated to “reinventing” high school, we’re still far from delivering engaging, relevant experiences that enable young people to explore, plan, and prepare for their life after school. In fact, according to a recent Burning Glass analysis of thirty states, only 18 percent of the credentials earned by K–12 students are demanded by U.S. employers. And no state has successfully matched its supply of credentials K–12 students with demand in the job market.

Our inability to transform the high school experience has been billed as a generational failure of education policy. But what if that failure isn’t wholly or even mostly about education policy at all?

Instead, if we want to remake high schools, we have to start with the tangled web of policies and programs that comprise America’s “workforce development” field.

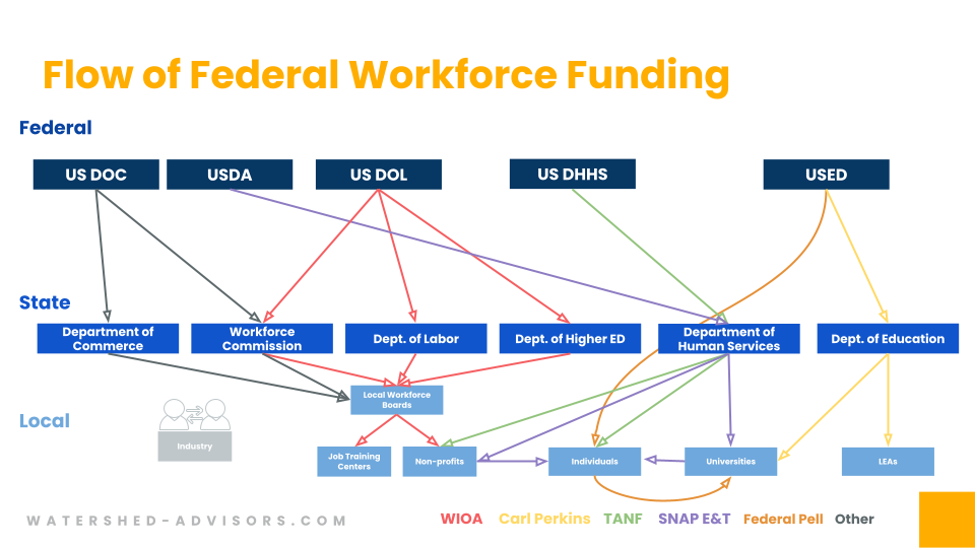

Today, workforce improvement efforts are funded by a variety of federal agencies and spread across a potpourri of state bureaucracies (departments of economic development, education, higher education, and social services), public institutions (community colleges and K–12 school systems), nonprofit organizations, and industry groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor, for example, allocates $3.6 billion through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act to local job training programs. But because the money passes through regional, state, and local workforce boards, much is lost to administrative costs. The same agency runs an entirely separate, $120 million Registered Apprenticeship program to connect apprenticeship seekers with employers. And the Department of Commerce’s Good Jobs Challenge recently gave states $500M to reduce barriers to training in fifteen growing industries. The Department of Education’s Pell grants are a significant source of funding for low-income undergraduates, yet they fund just a fraction of yearly tuition, and policy restrictions prevent them from being used for shorter-term training programs that could lead to valuable industry credentials.

These are just a few examples, but they point to a system so fragmented that it’s hard to navigate for state and local agencies, let alone a high school guidance counselor or rising sophomore. In fact, our team recently mapped out these funding streams and requirements. The resulting graphic was so convoluted that we’ve started calling it the “spaghetti chart.”

The upshot is that while great apprenticeship and certificate programs do crop up, they reach far too few students.

To be sure, there are promising pockets of innovation at the state and local levels. States have reworked high school graduation requirements to include completion of an industry-based certification, partnered with community colleges to expand career and technical coursework, and attempted to use the Perkins funds to align their offerings to regional economies. But these examples remain the exception rather than the rule because there are limits to what the K–12 field can accomplish without addressing the convoluted workforce system surrounding it.

And so the status quo largely persists. The vast majority of college-bound students fill their days with coursework to meet admission requirements, leaving few opportunities for hands-on career learning opportunities. Those who are not planning on college tend to complete their required coursework by junior or senior year, leaving significant flexibility in their schedules. The free time could be spent earning industry-valued credentials in well-paying, fast-growing fields that do not require a college degree. Yet far more high schools offer extra study halls or early release than a chance to earn the skills and certification for in-demand jobs.

We can and must do better. For years, we’ve looked to superintendents and principals to single handedly reimagine high school. That’s not realistic. We can’t expect local educators alone to reorganize a system that stretches outside of education and beyond city and state lines.

It’s not a perfect analogy, but our work at the Louisiana Department of Education to streamline the state’s once-fragmented early childhood system points to some potential solutions. There, we created regional planning structures, allowing families to more easily access the seats available to them. The state established regional intermediaries that governed the various state and federal funding streams, administered a single application to ease families access to that money, and supported classroom-level improvement. The goal is simple: to ensure that the end users—whether it’s young families or high school students—can easily make programs meet their unique needs.

In the high school context, that could mean creating regional planners that are accountable to mapping future careers, aligning training resources with those careers, and creating multiple pathways that help high school students understand and access their options.

But as specialists in the education policy space, we also know our knowledge on this issue is limited. In fact, that’s kind of the point here. Perhaps setting students up for postsecondary success will require changing the structure of Pell, so that it unlocks a broader range of learning and career opportunities. Maybe WIOA can be streamlined to more directly put money to work for trainees. Or the Good Jobs Challenge could be used as a template for governors to incentivize regional partnerships. Whatever the specifics, we firmly believe that our best shot at reimagining high school requires deep partnership between policymakers in both education and workforce policy. It’s time to get moving. We don't have another fifty years to waste.