Nothing better evokes education reform’s predicament today than what occurred in late July when the National Basketball Association restarted its 2020 season. Players were given the option of featuring on the back of their jerseys one of about thirty messages. At least eleven players chose “Education Reform.”

Education reform has moved to the multimillion-dollar athlete from intrepid but impoverished policy wonks and reform advocates. We’ll see if that’s a welcome move. But the anecdote reflects a serious dilemma for the education reform movement: It’s become the equivalent of an athlete’s tagline with uncertain meaning.

Symbolism aside and truth to tell, much of the political dysfunction and gridlock that besets our lives today characterizes the education reform movement, too. Pundits from the left and right have recently declared the end of the more or less three-decades-long center-left/center-right coalition that advanced issues like standards, testing, accountability, teacher evaluation, and charter schools. That coalition has decoupled.

I’m not ready to give up. I believe a renewed coalition can be created that unites former members with fresh allies to revitalize education reform. The need for reform is still great. While some progress has been made, learning gaps between White and minority students remain, achievement trends have flattened in some domains, and the pandemic has brought on its own learning losses.

This project should be based on an opportunity framework with a social capital perspective. Its goal is for every American, regardless of age, color, gender, etc., to develop and deepen habits of mind and of association that build their capacity to pursue opportunity and a prosperous life.

This approach asserts three broad value propositions that I take to be centrist and potentially bipartisan, even nonpartisan, when applied to educating young people. First, knowledge and networks are essential to preparing people to access opportunity. Second, local initiatives and mediating institutions, including the familiar (if tattered) organizations of civil society, are crucial to creating coalitions and lasting programs. Third, preparing young people for adult life, work, and citizenship includes cultivating an occupational identify and vocational self.

I base my proposal on Joseph Fishkin’s notion of opportunity pluralism and offer two examples, chosen to illustrate the framework’s applicability to a current education policy issue: career pathways programs that link students and schools with employers and work. I conclude with reflections on how this approach contributes to a young person’s development of an occupational identify and vocational self.

Opportunity pluralism

University of Texas law professor Joseph Fishkin has written on how opportunities are structured and accessed by individuals, including how education’s credentialing process for work and career contains bottlenecks that deter opportunity. He argues for opportunity pluralism, a structure that offers individuals multiple education, training, and credentialing pathways to work and career. They include but are not limited to the four-year college degree. Instead of struggling to equalize opportunity on a single pathway, Fishkin contends, the range of opportunities for individuals at all life stages must be broadened and deepened.

The institutional opportunity structure includes at least four education and training sectors—K–12, postsecondary, workforce training, and employers. Each plays a significant role in developing diverse pathways that connect individuals and schools with employers and work.

An opportunity framework

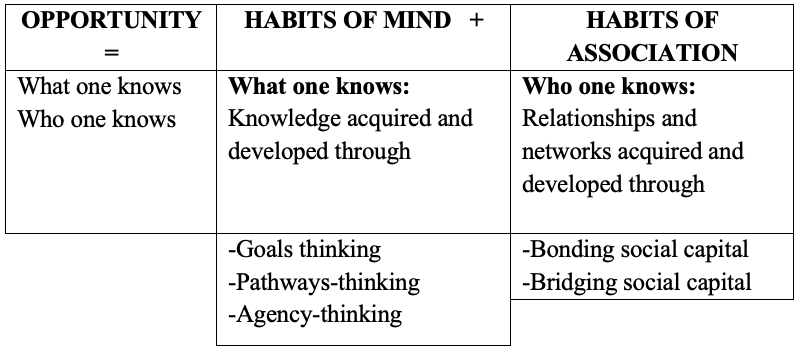

The framework combines what students know—knowledge—with whom they know—relationships. It recognizes the cultivation of habits of mind and of association as building blocks of individual opportunity.

Habits of mind are the basis for an individual’s hope that he or she can shape future circumstances and comprise three modes of thinking. They include goals thinking (defining and setting achievable outcomes), “pathways-thinking" (creating a route to these outcomes), and agency-thinking (pursuing goals and pathways through personal agency and self-efficacy). Pathways- and agency-thinking together foster the pursuit of goals, helping individuals overcome the obstacles that life will place before them.

Habits of association involve the accumulation of two kinds of social capital: the “bonding” kind and the “bridging” (or “leveraged) kind. Bonding social capital occurs within a group, reflecting the need to be with others and thereby obtain emotional support and companionship. Bridging social capital occurs between social groups, reflecting the need to connect with individuals different than ourselves, expanding our social circles across features like race, class, and religion. Bonding and bridging social capital are complimentary. As Xavier DeSousa Briggs says, binding social capital is for “getting by,” and bridging social capital is for “getting ahead.”

Analysts from the left—e.g., Robert Putnam—and right—e.g., J.D. Vance—affirm the importance of social capital in the lives of individuals, local communities, and the nation. This notion has a long history of support from a variety of ideologically diverse analysts, going back in recent times to James Coleman and his work on adolescents and schools. For this reason, the network approach to social capital and opportunity has the potential to unite divergent political orientations and beliefs.

This figure illustrates the main elements of an opportunity framework, as showing in Table 1.

Table 1. An opportunity framework

In shorthand: Opportunity = Knowledge + Networks.

Opportunity requires a judicious combination of what and who one knows. What one knows entails habits of mind focused on learning content knowledge using several modes of thinking. Who one knows involves habits of association focused on relationships and networks developed through the two modes of social capital.

They are habits insofar as they encompass patterns of conscious behavior and responsible conduct learned and internalized through practice. They are also moral strengths whose responsible exercise leads to virtuous behavior—i.e., developing an individual’s talents to full potential and increasing that person’s life opportunity and worthy citizenship.

Examples

Such a framework can help K–12 schools foster knowledge and networks via activities such as student-employer apprenticeships and internships; career and technical education; dual enrollment in high school and postsecondary institutions; job placement and training; career academies; boot camps for acquiring discreet knowledge and skills; and student staffing and placement services.

Here are two illustrations initiated by state governors of different political parties.

Delaware Pathways was initiated in 2014 by Democrat Jack Markell to provide college and career preparation for youth in grades seven to fourteen. Its goal was to create pathways from school to careers aligned with state and regional economic needs, especially for middle skills jobs.

Middle school students learn about career options and then, as high school sophomores or juniors, take career related courses. High school students can take college classes at no cost to families, serve as interns, and earn work credentials. Beginning in the summer before senior year, students participate in a 240-hour paid internship that lasts through the year.

The program engages K–12 educators, businesses, post-secondary education, philanthropy, and community organizations. For example, Delaware Tech is the lead agency that arranges work-based experiences. United Way coordinates support service for low-income students. Boys and Girls Clubs and libraries provide after school services.

Currently, Delaware offers pathways in fields like advanced manufacturing, engineering, finance, energy, CISCO networking, environmental science, and health care. Over 9,000 students are enrolled, around 45 percent of the state’s high school students. Many also take career related courses at institutions of higher education and earn credit that can be applied to associates degree or certificates.

On the Republican side, Tennessee’s Bill Haslam created the Drive to 55 Alliance in 2015, a partnership between the private sector and nonprofits intended to equip 55 percent of Tennesseans with a college degree or training certificate by 2025. Its five programs, three pertaining to K–12, create partnerships among school districts, postsecondary institutions, employers, and community organizations.

First, Tennessee Promise Scholarship provides last-dollar support for high school graduates attending community or technical colleges, including linking Promise students with private sector volunteer mentors and nonprofit partners.

The second program is Tennessee Reconnect, a counterpart to TN Promise, offering a last-dollar grants for adults to earn an associate degree or technical certificate, tuition-free.

Third, Tennessee Pathways promotes a college and career approach to K–12 schools and grants a Department of Education pathways certification to programs with strong alignment among high school programs, postsecondary partners, and regional employment opportunities.

Next, the SAILS program is for high school students who did not reach the ACT college readiness benchmarks in mathematics. It provides in-person and online learning so students can complete math modules for postsecondary credit so they don’t need remedial math in college.

Finally, Tennessee Labor Education Alignment Program or LEAP is directed to four-year post-secondary institutions. It links them with employers so colleges can offer programs aligned with actual employer workforce needs.

Linking all these programs together is an online portal called CollegeForTennessee, providing planning tools for career and college for students, counselors, and educators.

Opportunity pluralism and a vocational self

All this is about providing young people with new ways to acquire habits of mind and association that develop an occupational identify and vocational self. This includes placing student knowledge acquisition, engagement, and networking at the center of program design. Developing knowledge and awareness of oneself as a worker within the broader sense of one’s abilities, personality, and values is an important foundation for adult success and a lifetime of opportunity.

Such programs also use developing habits of mind and association that lead to a vocational self—e.g., apprenticeships, internships, boot camps, income share programs, staffing and placement services, etc. They create new ways that K–12 education and partner organizations develop an individual’s talents to his or her full potential, increasing that person’s ability to pursue opportunity over a lifetime.

They exemplify what Ryan Craig calls “faster and cheaper” pathways to jobs and careers than is generally possible in traditional education settings. And they take a pluralistic approach to accessing opportunity—i.e., they create a range of pathways to opportunity and lifelong well-being.

Such a framework could rekindle an expanded reform coalition of diverse policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders who believe expanding opportunity for young people includes developing their knowledge and networks. If we can’t come together in pursuit of that mission, it will not only show lack of will. It will also reveal a lack of imagination on how to unite different factions of the education reform movement under a core set of values.