(Photo credit: Getty Images/XiXinXing)

(Trigger warning: This essay contains a bleeped, profanity-laced rant that may cause you to question your most deeply held beliefs.)

It's not often I cite vulgar, inappropriate humor to draw attention to the absurdity that occurs when someone sets achingly low standards and then expects accolades for surpassing them. But I cannot resist after re-discovering a raunchy (NSFW) skit from Chris Rock’s 1996 classic, savagely funny performance in “Bring the Pain”:

You know the worst thing about [bleeps]? [Bleeps] always want credit for some [bloop] they supposed to do. A [bleep] will brag about some [bloop] a normal man just does. A [bleep] will say some [bloop] like, "I take care of my kids." You're supposed to, you dumb [bleeper][bleeper]! What kind of ignorant [bloop] is that? "I ain't never been to jail!" What do you want, a cookie?! You're not supposed to go to jail, you low-expectation-having [bleeper][bleeper]!

I have been wondering how Chris Rock would re-write this skit as we enter the annual season in which a parade of education reform leaders triumphantly announce academic results marginally superior to the poor outcomes of the public education system we have committed our lives to transform.

You know the worst thing about ed reformers? Ed reformers always want credit for some [bloop] they supposed to do!

Take for example Richard Whitmire’s groundbreaking new series in The 74 entitled “The Alumni.” It highlights nine premier charter management organizations. Each network has been operating for nearly two decades or more, and each now can proudly and rightfully claim large numbers of high school graduates who have successfully completed college.

Indeed, rather than the standard dipstick measure of annual state test scores, Whitmire describes a remarkable paradigm shift in the way charter schools define success: “About a decade ago, 15 years into the public charter school movement, a few of the nation’s top charter networks quietly upped the ante on their own strategic goals. No longer was it sufficient to keep students ‘on track’ to college...nor enough to enroll 100 percent of your graduates in colleges. What mattered was getting your students through college.”

Fair enough! Once again, the charter sector would prove its dominance over the status quo and be an exemplar for how public school systems should be held accountable. Understandably, jubilant headlines like this one captured the impact: “Public Charter School Students Graduate From College at Three to Five Times National Average.” Who wouldn’t declare success when the results of these nine networks were compared to the reality that a mere 9 percent of children from low-income families go on to complete college by age twenty-four?

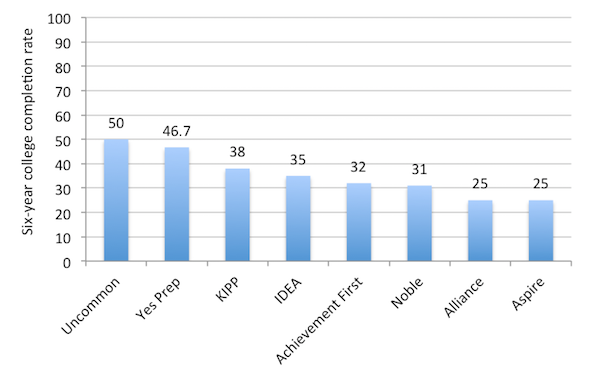

But, as Whitmire acknowledges, we must look closer. Figure 1 depicts the actual college completion rates for eight of the networks he profiles.

Figure 1. Six-year college completion rates at eight top charter networks

SOURCE: Richard Whitmire, “Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average,” The 74 (July 26, 2017).

Across the nine networks, the six-year aggregate completion percentage is 35 percent, not accounting for the size of each network’s student body. Yes, that only 9 percent of low-income students graduate in six years is a crime and a tragedy. But 9 percent is neither an expectation nor a standard. Each of the outstanding leaders of these networks would agree. And they all no doubt aim to have 100 percent of their scholars ultimately earn a degree. So a 35 percent four-year college completion rate in six years is actually an incredibly disappointing absolute outcome, especially for well-established charter networks that produce proficiency rates on state tests far higher than 35 percent.

9 percent? You beat nine percent! What do you want, a cookie?!?

What's more, these completion percentages are likely lower when measured against a more rigorous, accurate standard. For example, in KIPP’s report, The Promise of College Completion, the network emphasizes that measuring college completion accurately begins by tracking “students’ progress starting at the end of eighth grade or the beginning of ninth grade to get a clear picture of KIPP’s impact on our students’ educational attainment. Some educational organizations and reports only measure the college success of high school graduates—an approach that fails to count the students who drop out before earning a high school diploma.” And indeed Whitmire notes that all of the charter networks included in figure 1, except KIPP, do just this.

“Starting counting in 12th grade.” What kind of ignorant [bloop] is that?

Moreover, a four-year degree should take four years to complete, right? Wrong.

The 1990 Student Right-to-Know Act established the nationwide requirement that postsecondary institutions report the percentage of students who complete their program within 150 percent of the normal time for completion (e.g., within six years for students pursuing a four-year bachelor's degree). So the federal government set the six-year time-to-complete measure for consumer information for colleges and universities. But that additional two years represents a significant additional burden of time and money, which could be especially devastating for low-income students. Charters, as the laboratories of innovation within K–12, are neither morally nor legally obligated to use this federally imposed low-bar metric to measure their college completion outcomes.

At Public Prep, for example, the pre-K–8 charter management organization I lead, forty-five scholars started first grade in 2005 when Girls Prep opened as the first and, at the time, only all-girls public charter school in New York City. Because we accepted transfer students—or “backfilled” to replace attrition—throughout the ensuing years in the upper grades, forty-seven Girls Prep scholars actually graduated from eighth grade in 2013. In 2017, an amazing 90 percent of that inaugural cohort of forty-seven graduating Girls Prep scholars were accepted into and will be attending some of the finest colleges and universities in the country, some of which are highlighted below:

Four years from now—not six—we will measure college completion rates for all forty-seven scholars. If we learn that it takes longer for them to earn their degree, then we will work to understand the factors driving the delay and adjust our strategies to help them get closer to on-time completion. But we won't change the measure.

A [bleep] will brag about some [bloop] a normal college student just does. A [bleep] will say some [bloop] like, "My kids graduate in six years." You're supposed to graduate in four years, you dumb [bleeper][bleeper]!

***

College completion rates are not the only area in which standards for comparison are regularly lowballed in the ed reform world. Take for example the obsession among education policymakers to close the racial achievement gap. In July, the National Center for Education Statistics released some “good news” in its report Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups. On the 2015 fourth grade NAEP reading assessment, the white-black gap narrowed from thirty-two points in 1992 to twenty-six points in 2015. And the white-Hispanic gap of twenty-four points did not get worse from 1992 to 2015.

Yay? Hardly.

The same NAEP 2015 data revealed that more than half of all white fourth graders—1.25 million white children—are not reading at proficiency, far surpassing any other racial group in raw numbers. Indeed, only 34 percent of all American fourth grade students of all races performed at or above the “proficient” achievement level in reading. Who cares if the black-or-hispanic-to-white achievement gap has barely closed over twenty-three years, if at all, when the majority of white kids can’t read proficiently either and closing the racial achievement gap would simply mean virtually everyone is mediocre?

You're not supposed to just equal low-performing white kids, you low-expectation-having [bleeper][bleeper]!

What’s worse is that myriad states have defined “proficient” to mean something less than college ready. Far too many “proficient” students require remedial courses when they matriculate—and their college completion rates are woefully low compared to their more advanced peers.

This fact is often glossed over, however. Take, for example, the common practice of lumping “proficient” and “advanced” scores on state tests into one consolidated measure. When district and charter schools report proficiency, the percentages are overwhelmingly made up of scholars who fall short of advanced scores. But these higher marks are much more reliably indicative of being on a college ready path.

***

We in the charter sector have to resist the temptation to go along to get along, even if the apparatus of mediocrity surrounding us incentivizes a race to the bottom (or at least just above the lowly status quo). Imagine if we were to take all five of these steps:

- Track college completion rates beginning after eighth grade instead of twelfth.

- Measure on-time, four-year college completion rates instead counting those who take six years.

- Focus on an achievement gap defined as how far we are from 100 percent proficiency instead of obsessing over gaps between races that are all performing poorly.

- Use unchanging, national benchmarks like NAEP to assess student progress instead of annually determined, politically motivated, state-set standards.

- Distinguish between “proficient” and “advanced” scores on state assessments instead of lumping them together.

If we took this handful of steps, the charter sector would be forced to confront the reality that the vast majority of kids who have been in our schools are not on a path to college completion. Perhaps then we would act with the appropriate urgency to both explicitly name and then address causal factors that truly impede our ability to achieve the academic and life outcomes we know are possible for our kids, such as the decline in family stability and the explosion in multiple births to unmarried women and men age twenty-four and under.

No one who has committed their lives to education reform signed up to measure ourselves against a despicably low standard that represents nothing more than the failed system that we are trying to improve. Achieving student results only marginally better than that low standard also offers no solace whatsoever.

In the must-read bible on college completion, Crossing the Finish Line, the authors describe the students most likely to earn a degree as possessing character traits that “often reflect the ability to accept criticism and benefit from it, and the capacity to take a reasonably good piece of one’s work and reject it as not good enough.” As the charter sector embarks upon its next twenty-five years, leaders should be proud to celebrate the progress we have made and the positive impact we have had on children.

Simultaneously, while we recognize charter school accomplishments as reasonably good, we should reject our work as still not good enough.

Let’s start by ensuring the metrics against which we measure ourselves and our students’ outcomes truly place them on a path to college completion. Let’s shift our focus to absolute results that are aligned with the highest of expectations instead of being continuously shielded by relative comparisons to the pitiful outcomes of a dysfunctional system.

Yeah, that’s what we’re supposed to do!

_________________

Editor’s note: Click here to read part 2 of this article.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.