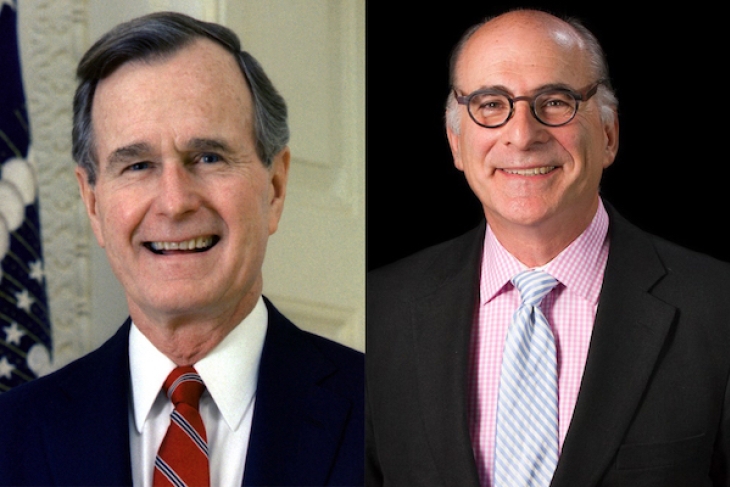

American education lost two great leaders last week with the passing of George H.W. Bush and Harold O. Levy.

It’s likely they never even met, as they came from different worlds and moved through the education solar system on different orbits. They belonged to different political parties and hailed from different generations. Yet their contributions to the betterment of K-12 education in the United States were both large and in interesting ways parallel.

Bush was a New England aristocrat turned Texas oilman turned politician and government official. Save for his time as ambassador to the United Nations, he never lived in New York. Levy, on the other hand, was a quintessential New Yorker, the son of Jewish refugees, a Wall Street lawyer who ultimately became the city’s schools chancellor and then head of an important private foundation.

Yet each was, in his way, an education leader, a visionary even, a champion of both excellence and equity, the head of large enterprises, and the source of a durable and influential legacy.

In 1988, campaigning in New Hampshire, Bush declared before a high-school audience that “I want to be the education president.” No U.S. president nor (to my knowledge) serious candidate had ever before said anything of the sort. Education wasn’t the business of the federal government—isn’t even mentioned in the Constitution. But Bush had served as Reagan’s vice president when A Nation at Risk emerged. Within months of its publication, he was hosting the governors for lobsters and education talk at Kennebunkport, along with education secretary Ted Bell. Though a number of governors, especially in the south, were already at work on boosting the educational performance of their states, there was much grumping at the Maine confab about the dearth of comparable state-level data on education performance and the absence of any sort of overall strategy for addressing the country’s level of education risk. Bush took it in—and asked Bell to do what he could. Among other things, this led to the infamous “wall chart” that paved the way for state-level NAEP testing a few years later.

In Bush’s second term as VP, Bill Bennett was education secretary and ideas began to fly for ways to tackle the education problem. The National Governors Association, led by Tennessee’s Lamar Alexander, launched a five-year initiative to examine the problem and possible solutions to it. Bush himself began to visit schools and immerse himself more deeply. (While working with Bennett, I once had the thrill of accompanying the VP and Barbara Bush on Air Force 2 on a school-visit trip.) Yet there was still no coherent national strategy, certainly nothing that linked state and federal actions.

When Bush reached the Oval Office on January 20, 1989, one of his first moves was to summon the governors to an education “summit.” This was only the third time any president had convened such an extraordinary session—both Roosevelts had done so on other issues—and the first time that education was the topic.

What emerged from that September’s gathering, which prominently included Arkansas’s Bill Clinton and was orchestrated by talented White House staffers, was a joint declaration of “national education goals” for the year 2000. It was overly ambitious to be sure, almost naively so, yet in the wake of the Charlottesville summit came the sequence of events that dominated American K-12 education policy and practice for a quarter century. It led to Bush’s own “America 2000” plan (crafted largely by education secretary Lamar Alexander), followed by Bill Clinton and Dick Riley and “Goals 2000,” as well as 1994’s Improving America’s Schools Act, followed by No Child Left Behind and all that was linked to it under Bush 43 and Barack Obama. One could make a pretty good case that 2015’s ESSA legislation (also crafted by Alexander) marked a sort of return to “America 2000,” albeit with many residual elements of NCLB.

Obviously, George H.W. Bush wasn’t solely responsible for all of this. If you wanted to minimize his contribution, you’d say he caught a wave that was already headed ashore. But that’s not right. I see him as a guy who jumped onto a slow-moving vehicle that had no particular destination and both pressed the accelerator and grabbed the wheel. (Recall how much he liked to take the tiller of a speedboat.) He also had, if not a precise end point in mind, at least a clear rationale for the direction in which he was steering. Consider this from his 1990 State of the Union address:

[T]he most important competitiveness program of all is one which improves education in America. When some of our students actually have trouble locating America on a map of the world, it is time for us to map a new approach to education. We must reward excellence and cut through bureaucracy. We must help schools that need help the most. We must give choice to parents, students, teachers, and principals; and we must hold all concerned accountable. In education, we cannot tolerate mediocrity. I want to cut that dropout rate and make America a more literate nation, because what it really comes down to is this: The longer our graduation lines are today, the shorter our unemployment lines will be tomorrow.

So, tonight I’m proposing the following initiatives: the beginning of a $500 million program to reward America’s best schools, merit schools; the creation of special Presidential awards for the best teachers in every State, because excellence should be rewarded; the establishment of a new program of National Science Scholars, one each year for every Member of the House and Senate, to give this generation of students a special incentive to excel in science and mathematics; the expanded use of magnet schools, which give families and students greater choice; and a new program to encourage alternative certification, which will let talented people from all fields teach in our classrooms. I’ve said I’d like to be the “Education President.” And tonight, I’d ask you to join me by becoming the “Education Congress.”

Thank you, President Bush. May you rest in peace and may your contributions to the renewal of American education receive the recognition and accolades they deserve.

***

Harold Levy died far too young and from an especially cruel disease. You would do well to view an exceptional tribute to him in October 2017—at a gala celebration of his life that he was present to appreciate—by Bard College president Leon Botstein, whose words also evoke some of what it was like to work with the brilliant, impatient and forward-looking chancellor. I had the sad pleasure of visiting with Harold a few months ago; he wasn’t able to speak but proudly led me to his desk so I could view on his computer screen a video-recording of that entire marvelous event.

While in the role of New York City schools chancellor—for less than two years between 2000 and 2002—he launched the terrific Teaching Fellows program to bring able but unconventional people into the city’s classrooms. A graduate of the Bronx High School of Science, he established three more selective-admission high schools. To forestall social promotion, he organized summer school for hundreds of thousands of students who had failed their regular classes. He pioneered “early college high schools” (one of them with Botstein’s Bard) to give able kids a faster track into higher education. He strengthened the student information system, hacked at regulations, and outsourced the management of failing schools, all the while working with the city’s powerful teacher union on a new contract that significantly boosted pay and thereby drew many more qualified applicants to seek instructional posts in the district.

In 2002, with the arrival in City Hall of Michael Bloomberg and Joel Klein, Levy returned to the private sector but didn’t depart the education scene. First with the Kaplan Educational Foundation and then with a venture capital firm that invested in schools and education technology, he stayed interested and involved. This led in 2014 to his final position, as head of the D.C.-based Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, where in just a few years he turned what had been a quiet, almost invisible philanthropy into the country’s most consequential player in the realm of education for smart poor kids. The Foundation’s signature program is a suite of scholarships that enable thousands of such youngsters to get a topnotch high school and college education.

The scholarships weren’t new. But under Levy’s leadership and propelled by his considerable energy and personal charisma, the Foundation also became a major source of support for policy initiatives in the gifted-education space, research projects, and innumerable related ventures, such as the marvelous Sunday evening “From the Top” program, showcasing (on radio) outstanding young classical musicians. At least as important, it helped to boost the issue of educating gifted young people—and, especially, closing the “excellence gap” by creating opportunities for smart kids from poor and minority backgrounds—to the visibility that it deserves but historically had not received. Harold, one might say, was pretty good at getting attention and didn’t mind it one bit. But he was no show horse. He was a brilliant, tireless visionary and first-rate executive.

May you, too, rest in peace, Harold Levy, and may your heirs, successors, and followers continue to champion the missions that you expertly led us into.

***

Levy was a liberal, through and through, and a lifelong Democrat. Bush was an old-school conservative and for decades the embodiment of the GOP (which for a time he actually chaired). Each pursued many other issues and held multiple roles outside education. Both were wealthy men who didn’t need the headaches of public-education reform but turned to it because others needed better schools and opportunities. When they made that fateful turn, both shared key commitments and values. They sought to give kids more and better choices. They pursued high standards. They focused on achievement, on equalizing opportunity, and on excellence, all together and all at once. In time, they both painted with nationwide brushes and did so with persistence, imagination, the capacity to enlist others, and the ability to get lots and lots of others to understand key problems and the importance of solving them.

At a time of anger, division, self-absorption and small-mindedness in so many places, it’s both refreshing and inspiring to remind ourselves that it doesn’t have to be that way and to recall two great Americans who embodied that abiding truth.