In a recent Fordham article, Daniel Buck makes several thoughtful critiques of the practice of schools that have replaced the mark of zero on a 100-point scale with a minimum grade of fifty. In my article, “The Case Against the Zero,” I argued that the zero, when combined with the use of the average to calculate the final grade, leads to mathematically inaccurate distortions in determining the student grade. I appreciate Buck’s expectation for high levels of performance and his rejection that 60 percent should be deemed passing, whether in high school algebra or brain surgery. I also appreciate Buck’s consideration of the finite nature of teacher time and the futility of students bringing in a truckload of missing assignments on the last day of the semester and expecting teachers to absolve them for months of late work. Thanks to the Fordham Institute for this opportunity to clarify my views now, almost eighteen years after the original article was published.

First, students do need consequences for failing to submit work. The only question is what the most effective consequences should be. If F’s, zeroes, and point deductions were effective consequences, then after a few centuries of these experiments in student motivation, all student work in 2022 should be on time and perfect. I know of no teachers on the planet who make such a claim. The penalty for not turning in work should be doing the work, and schools around the nation have been very clever in creating consequences that are effective. These include constraints on student time and space, with the requirement to get work done when it is due. Some brilliant athletic coaches do not allow students to suit up until homework is done. In other schools, there is a “quiet table” in the lunch room (expanded in other cases to a “quiet room”) to finish work. Students crave freedom and independence. These are consequences that work when threats of F’s, zeroes, and point deductions are futile.

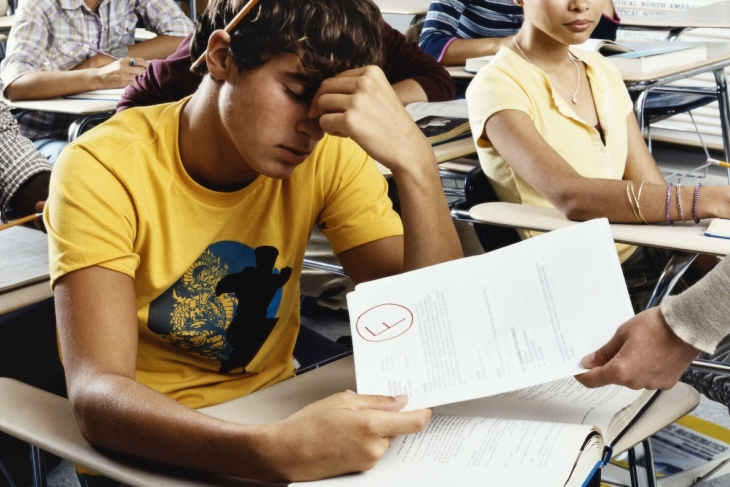

Second, the problem is not just the zero, but the default of electronic grading systems to the average. This is why the zero becomes the academic death penalty. Far from incentivizing students to be diligent, the zero, when combined with the average, tells the student that all the blather about resilience and perseverance that they hear from their teachers is just so much hot air. After a few zeroes early in the semester, it becomes impossible to pass the class. This is why the last few weeks of every semester are plagued by chronic absenteeism and disruptive behavior. When academic success is impossible due to the use of the average, why bother?

Buck’s reference to surgeons is quite appropriate. We don’t evaluate surgeons based on the average of their early mistakes on cadavers but rather on their proficiency with real patients. Indeed, we expect surgeons, pilots, and a host of other professionals to make mistakes, learn from those mistakes, and improve their skills as a result of that learning. The same emphasis on learning from mistakes, getting feedback, respecting and applying feedback, and ultimately improving performance should be the focus of classroom work in schools. When I have interviewed employers and college professors, they disdain the idea that everyone gets it right the first time. In fact, they seek employees and students who can make mistakes and accept feedback without calling their mother, therapist, and lawyer. Our grading systems should reward response to feedback and quit with the fantasy that every student gets things right the first time. Besides, we learned during the pandemic that “perfect” homework may be more likely credited to Google and Kahn Academy than to the individual work of students.

Third, I have no problem with the zero, as long as it is mathematically accurate. Let us return to the good old days in which report cards were not on the 100-point scale, but on a much smaller scale, sometimes with letters, and sometimes with Latin descriptions. Most people are familiar with simple A–F grading, in which A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1, and F=0. This is the way that most schools calculate grade-point averages, and it has much to commend it. I trust teachers to tell their students the difference between an A and a B, a B and a C, and so on. But no teacher can persuasively explain the difference between a 32 and 33, a 75 and 76, and—here is where the blood is spilled when grades are reported—an 89 and 90, or 59 and 60. These one-point variations are classic distinctions without a difference.

Buck and I want the same thing—students who respect teachers, organize their work, meet deadlines, and learn the habits of responsibility and diligence. My respectful suggestion is that we pursue these goals with techniques that actually work rather than persist in a system of zeroes and averages that undermines the very character traits we seek to instill.