Every now and then, the cracks that form at the intersection of housing and education policy become visible to a casual observer. An overcrowded school building. A desperate family that commits “residency fraud” so its kids can learn. A homeless parent who struggles to enroll her children in a local school.

Yet too often such fissures are undetectable to all, save the case workers and educators who do their best to patch them (with mixed results). One day Johnny is scraping out a D-minus in English. The next day he’s gone, carried away by circumstances beyond his control—social, economic, familial—to unfamiliar streets and classrooms unseen.

Alas, Johnny’s experience is far from unique. Roughly one in five poor families in the United States changes residences each year, often involuntarily. Worse, because the housing and education markets are linked, involuntary changes in residence often force already-vulnerable students to change schools, at least when their new address is sufficiently distant that they wind up in another attendance zone.

It follows that, insofar as school choice weakens the link between housing and education, it may hold particular benefits for students who experience “residential instability.” Families would surely benefit from being able to change homes while keeping their children at the same school. Yet, to our knowledge, this potential benefit has never been studied, perhaps because doing so requires a dataset with detailed information on students’ home addresses.

That’s why we were excited to learn of the dataset that the University of North Carolina’s Douglas Lee Lauen and his research assistants have painstakingly assembled. Professor Lauen is well-known for his prior work on charter schools and educational accountability and, like us, was eager to shine a bright light on this neglected dimension of school choice. In addition to information on student demographics, achievement, attendance, and discipline, his database includes the home addresses of every student who enrolled in a North Carolina public school between 2016–17 and 2018–19. This unusually rich dataset, which includes information on more than four million students, enables analysis of the relationships among residential mobility, school mobility, and charter school enrollment.

Fordham’s resulting report—titled New Home, Same School: Charters and residentially mobile students and authored by Lauen—is worth reading in full. But here are its four key findings.

First, about one in seven students experiences a change in residence or school in a given school year. Moreover, there is a strong link between residential and school mobility. It’s hard to say how many of these moves are “involuntary,” but they’re more frequent among low-income families.

Second, Black and Hispanic students are more mobile than White students. For example, Black students are about twice as likely to change schools as White students (and about two-thirds of those moves are accompanied by changes in residence). In other words, racial disparities in school mobility are effectively baked into a system in which housing and schooling stay linked.

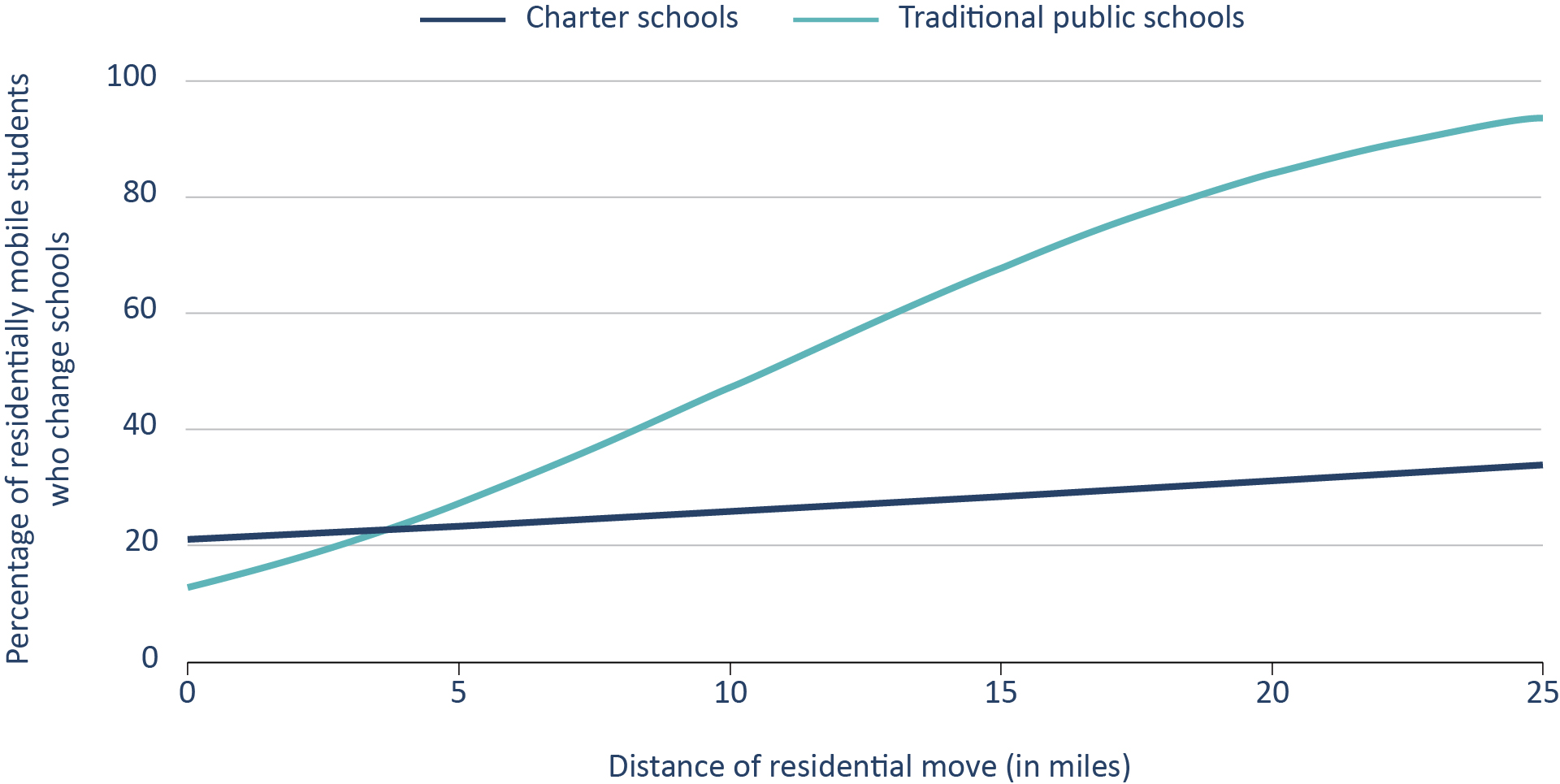

Third, residentially mobile students in charter schools are less likely to change schools than their counterparts in traditional public schools. More specifically, the former become less likely to change schools relative to students in traditional public schools as the distance of the residential move increases (Figure 1).

If you think about it, this makes sense: The further a family moves, the more likely its kids are to wind up in the catchment zone of a different traditional public school or an entirely different district. But most charter schools don’t have catchment zones so as long as any transportation barriers are surmountable, nothing prevents their students from remaining enrolled in the same school should where they live change.

Figure 1: As the distance of the residential move increases, students in charter schools become less likely to change schools than those in traditional public schools.

Notes: This figure shows how the probability of school mobility increases for residentially mobile students as the distance of the residential move increases. The sample includes only students who made a residential move of twenty-five miles or less. Traditional public school and charter school status are defined before the residential move. Estimates were generated using a probit model with distance of a residential move as the predictor and school move as the outcome.

Finally, residential mobility, school mobility, and “compound” mobility are all associated with a small decline in academic progress in math and a slight increase in suspensions. In other words, the results suggest that needlessly high mobility rates have real costs for students (and of course there could be other costs that we do not observe).

Isolating these adverse effects is challenging, as is generalizing about the various scenarios that can result in a student changing schools. (Consider the difference between a student who is expelled and a student whose parent takes a higher-paying job in a better-resourced community.) Still, if there’s no reason to believe that a student’s new school will be better than their old one, it’s hard to endorse a regime that forces families to change schools when they change homes.

—

“Freeing” students in low-income neighborhoods from low-performing schools remains a key benefit of school choice. But another, albeit less obvious, benefit is reducing the educational disruption and personal stress that often come with a change in residence, especially for students in those same neighborhoods.

Every year, about 3 million children in the United States are evicted. As of 2022, about 1.2 million students were considered homeless by the U.S. Department of Education (though the true number is almost certainly higher). And in the past year, a combination of rising rents and the expiration of pandemic-era protections has created a housing crisis that has disproportionately affected students of color. Right now, in New York City alone, at least 100,000 kids are in temporary housing.

Obviously, school choice can’t address all of the factors underlying such tragic statistics or completely quell their consequences. But more robust and equitable open enrollment policies would be one step. More charter schools (which are legally prohibited from giving preference to students from “good” neighborhoods) would be another. And, regardless of how we attack the problem, the burden of proof should fall on those who insist that students who are already perilously close to falling through the cracks must change classes, teachers, curricula, and peer groups if and when they find a new home.

In short, the right to school choice is also about the right to stay put.