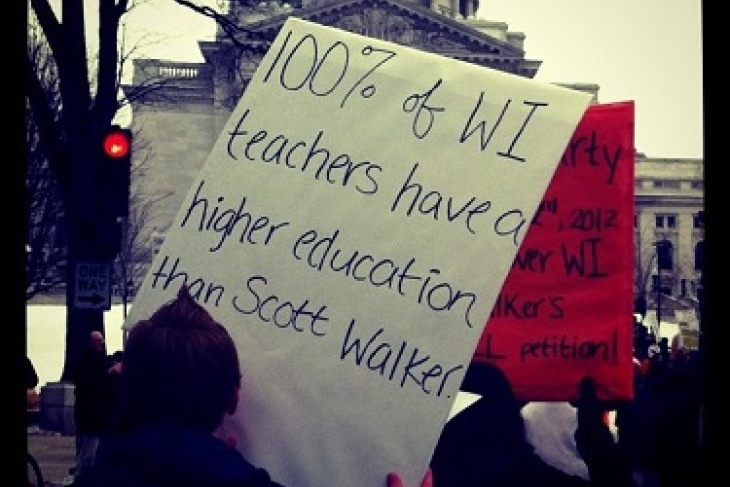

The pundit class is raising questions about whether Scott Walker’s lack of a college degree disqualifies him from being America’s forty-fifth president. This is what educators call a “teachable moment” because the issue goes much deeper than Governor Walker’s biography. Of course a college credential shouldn’t be a prerequisite for the presidency, but that’s also true for many jobs that today require a degree even when it’s not really necessary. That’s a big problem.

Many American leaders are obsessed with college as the path to economic opportunity. President Obama, for instance, wants America to lead the world in college graduates by 2020. But he’s hardly alone. Philanthropists, scholars, business leaders, and other members of the meritocratic elite have been banging the “college for all”—or at least “college for almost all”—drum for the better part of a decade.

Yet despite their own blue-ribbon educations, these leaders are making a classic rookie blunder: They mistake correlation for causation. They point to study after study showing that Americans with college degrees do significantly better on a wide range of indicators: income, marriage, health, happiness, you name it. But they assume that it’s something about college itself that makes all the difference, some alchemy at their alma mater that turns gangly eighteen-year-olds into twentysomething masters of the universe.

Sure, college can be a great experience, and many individuals gain important knowledge, skills, insights, and contacts there. It’s also a prerequisite for most graduate and professional schools. All of that can help to build the “human capital” that enables people to get good-paying jobs and then excel at them.

But much of the college advantage can be explained by “selection bias”—the differences between those who tend to complete college and those who don’t. The dirty little secret of college is that it tends to bestow a credential on those who are already most likely to succeed. To use another term from Statistics 101, “confounding variables” explain why college grads do better: Their reading and math abilities; their social skills; their wealth. If people with these underlying advantages did something with their time other than go to college, like start a business or serve in the military, they would still outperform their peers over the long term.

Furthermore, research tells us how college students do “on average” against their peers without degrees. But those averages can mask a lot of variation. As Andrew Kelly succinctly put it in a recent paper for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, “on average ? always.” He cites a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that found that the lowest-paid quartile of college graduates earns little more than average high-school graduates do; that’s been so since the 1970s. Which helps to explain all of those college-educated Starbucks baristas.

Back to Governor Walker. Our challenge as his prospective employer isn’t to determine whether presidents “on average” do better with a college degree than without one. It’s to consider Walker’s particular case. Does he have the knowledge and skills to do the job? What’s his track record in similar positions? We might conclude that his executive experience and legislative skills are quite solid but that his foreign-policy knowledge is a bit of a question mark. That’s the case with various successful GOP governors who are running for president. What matters isn’t whether they finished college thirty or forty years ago, but how they’ve been performing in recent years, what kinds of advisers they are associating with, and what that implies for their potential success as president.

Unfortunately, millions of Americans don’t have this same opportunity to make their case to prospective employers, because their lack of a degree locks them out of the recruitment process altogether. While there are indeed some jobs that require the knowledge and skills gained in college, surely receptionists and photographers are not among them. Employers use college degrees as a proxy for smarts, perseverance, and other valuable skills. But this shortcut unwittingly excludes many talented people from their prospective hiring pool. This is especially unfair since people who come from modest means (such as Walker) are most likely to be disadvantaged by this type of credentialism. As Charles Murray has argued persuasively, a much better system would be one in which employers “rely more on direct evidence about what the job candidate knows, less on where it was learned or how long it took.”

Scott Walker may or may not be the best candidate for president. But there’s little doubt that he should be in the candidate pool. The same goes for millions of his non-college-educated peers who want a shot at a good job. We should give them a chance.

Editor's note: This post appeared last week in a slightly different form at National Review Online.