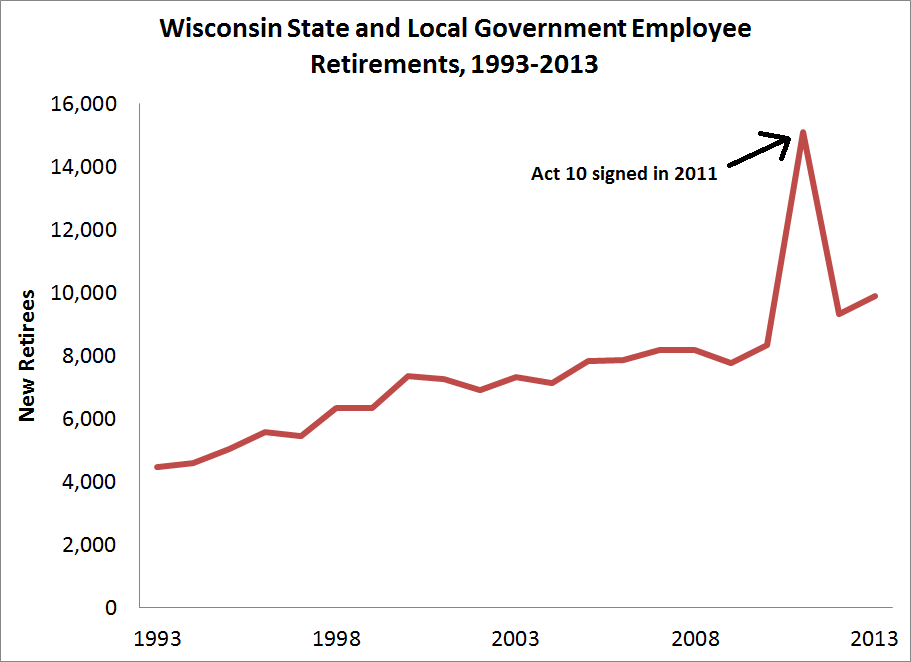

In the midst of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s controversial 2011 budget bill, many warned that the state’s public employees, including teachers, would retire in droves. The bill, commonly known as Act 10, limited public workers’ ability to collectively bargain on any topics other than base wages, increased their contributions to public pensions, and raised their insurance premiums.* The pension and health care increases immediately cut the take-home pay of public workers, combining with hostility toward Governor Walker to contribute to a wave of public worker retirements.

But the story didn’t end in 2011. After an initial 80 percent surge, the number of workers retiring fell back in line with long-term trends. Wages and staffing levels also appear roughly in line with historical trends. The initial retirement figures were large, but when put in context relative to the state’s total public sector workforce, the numbers weren’t as remarkable.

Let’s start with the historical data on retirements. Tracking retirement numbers back twenty years, the number of Wisconsin state employees retiring each year has climbed steadily, in line with growing numbers of state employees across the state. The graph below shows what this looks like. The data come from annual reports issued by the Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds. Note that these numbers include all public sector workers (the state doesn’t disaggregate results for teachers, but we’ll get to some numbers on teachers in a bit). As the graph suggests, there was a consistent climb in the number of retirements until 2011, the year Walker signed Act 10. That year, retirement numbers leapt from 8,330 to 15,096—an 81.2 percent increase in a single year. But since then, they’ve followed a more recognizable pattern.

While Act 10 did have an effect on retirements when it passed, looking at these numbers relative to the entire workforce paints a different picture. After rising steadily throughout most of the 1980s and 1990s, Wisconsin state and local government employment hit a plateau in 2002, hovering close to 260,000 until slightly dipping to 257,254 in 2011. Out of approximately 250,000 state employees, the 6,776 jump in retirements accounted for less than 3 percent of the total workforce. The 2011 bump seems far less dramatic within the larger state and local government workforce.

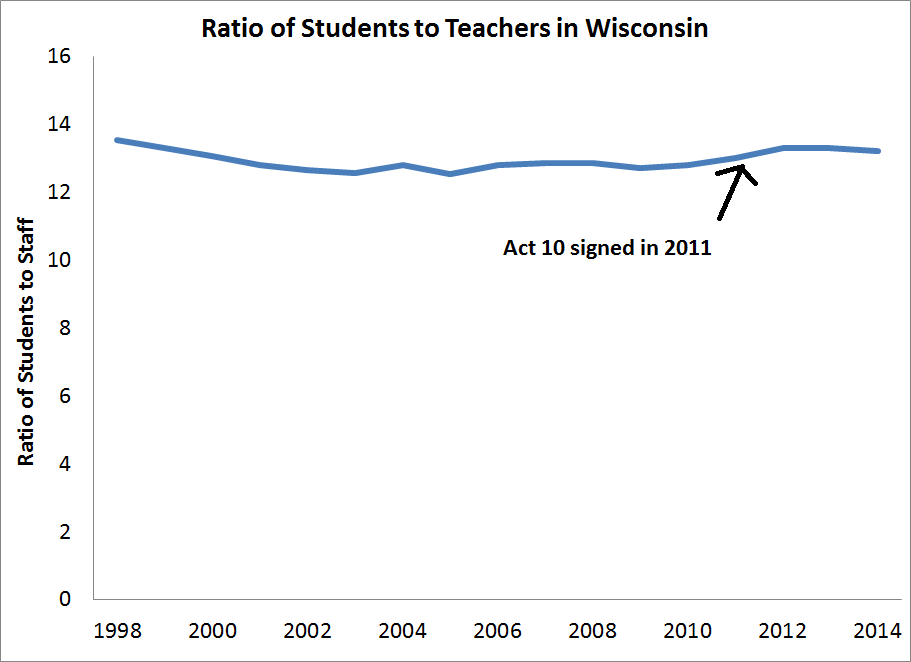

Although the state does not disaggregate the data on retirements for teachers, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does keep detailed information on the teacher workforce that allows us to examine the effects of Act 10. The total number of teachers statewide did fall slightly, and student-teacher ratios rose a bit. But those changes started in 2009—during the depths of the recession—and did not dramatically accelerate after Governor Walker signed Act 10 in 2011. The long-term trend in the student-teacher ratio looks relatively flat, with just a few minor dips and bumps along the way.

It’s still too early to tell if Act 10 will have any long-term effects on education in Wisconsin. But so far, at least, it doesn’t seem to have changed much beyond perception. Teacher experience levels are barely below where they were five years ago and about the same as they were ten years ago. The average teacher salary in Wisconsin remains just slightly above the middle of the pack, and Wisconsin is not losing ground when looking at changes over the last decade. (Take-home pay doesn’t show up in the data, but other states have also increased their employee contribution rates for pensions and health care.) There’s early evidence that some Wisconsin districts are changing their compensation plans to offer retention bonuses, supplemental pay, or higher pay for teachers who take on additional responsibilities.

Taken together, these data suggest that Wisconsin’s Act 10 may have pushed some government workers to retire immediately, but once the public outcry died down, the public sector labor market more or less returned to normal. We certainly haven’t seen the enormous drain of teacher talent that some predicted. Our hunch is that politics and state policy changes influenced retirement decisions in the short run, but outside factors like family, work environment, and personal preferences will continue to be the dominant factors influencing retirement trends going forward.

*A separate bill raised the vesting period (the experience level to qualify for at least a minimum pension) from zero years to five. Vesting periods change benefits for early-career workers, but they should not materially affect later-career retirement decisions.

Chad Aldeman is an associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of Teacherpensions.org. Kirsten Schmitz is former LEE Policy Fellow with Bellwether and is now a program coordinator at the Aspen Institute.