Over the past decade, I’ve deepened my belief in the power of letting educators form non-profits to run public schools. Both experience (walking into amazing public schools) and research (a track record of reading and math gains) have shown me that non-profits are an incredibly valuable tool in making public education better.

I’ve also deepened my belief in unified enrollment systems. They can give families a lot of information about public schools and make enrolling in public schools much easier.

I do not have deep confidence in my views on accountability. I often find myself moving up and down the spectrum of: no accountability (just let parents choose), to accountability-lite (require testing, share this information, but don’t intervene), to accountability heavy (require testing, give schools letter grades, intervene in lowest performing schools).

I think reasonable arguments can be made for all three approaches.

Recent NWEA Research

NWEA just published a new report using a national data set from the tests they license to schools. Many schools we work with use these tests. I’m not expert enough in statistics to evaluate the reliability of their findings, but the report raised some important issues.

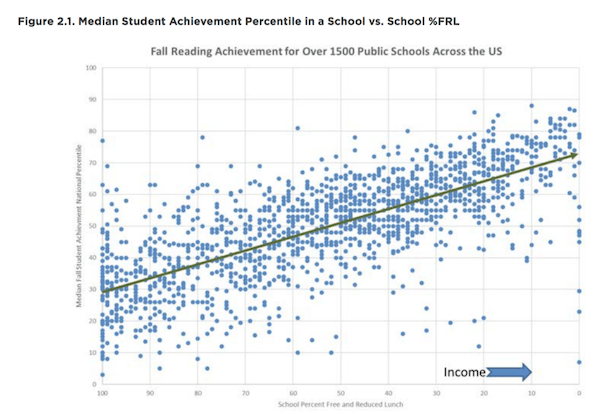

Absolute test scores are highly correlated with poverty. The chart below shows that test scores rise as income increases. This is not new information.

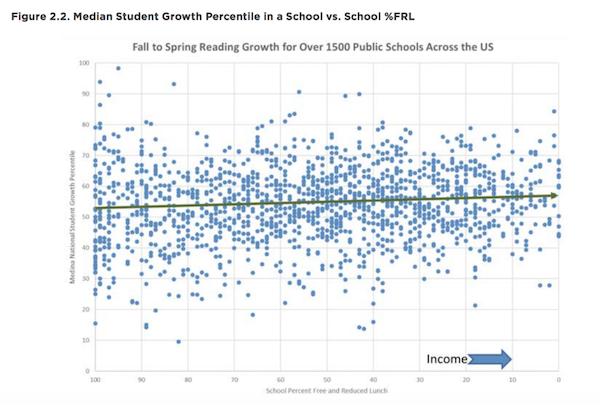

Student growth is not tightly correlated with poverty. Unlike absolute achievement, individual student growth does not rise significantly with income. Many high poverty achieve growth that mirrors those of their wealthier peers.

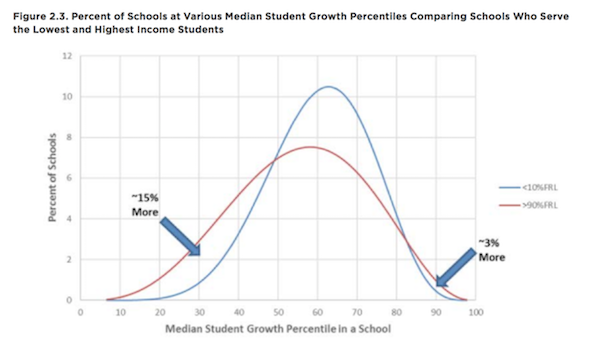

Schools with similar levels of poverty perform very differently on growth. The red line in the chart below represents how schools with high poverty perform on academic growth. It is a fairly wide curve. Many schools achieve low growth, while others achieve very high growth. To the extent you believe that growth is a pretty good measure of school performance (the researchers do), this performance spread might increase a policymaker’s willingness to intervene in low-performing schools and expand high-performing schools.

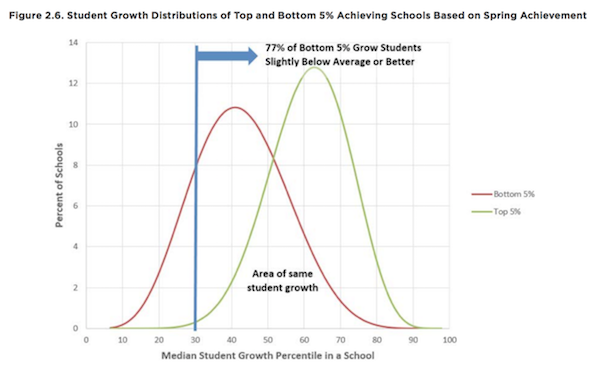

Focusing on absolute test scores will cause you to misidentify many, many schools. The graph below is tricky to read, but it’s very important. The red line represents all schools that are in the bottom 5 percent for absolute test scores. And it shows that 77 percent of these schools (the bottom 5 percent on absolute) are close to the average or better on growth. In other words, if you just closed the bottom 5 percent of schools based on absolute achievement, nearly 80 percent of the schools you’d close probably would be mistakenly closed (given their growth scores). This is pretty damning evidence against those who want to focus mostly on absolute achievement in accountability measures.

When does a good policy idea become indefensible because of bad practice?

Over the past few years, most states reworked their accountability systems during the reauthorization of No Child Left Behind.

Unfortunately, this report found that only eighteen states weighted growth for at least 50 percent of the total accountability score, with another twenty-three states weighting growth at least at 33 percent.

On one hand, this is an improvement over old accountability systems. On the other hand, this means a lot of states are unfairly rating high poverty schools that have decent growth but low absolute scores.

I think a fair critique of test-based accountability is that it’s a reasonable idea that has very little hope of being reasonably implemented.

My own thoughts

Again, I do believe deeply in letting non-profit organizations operate public schools. And I do believe deeply in enrollment systems that make it easier for families to find a great school for their children.

I’m uncertain about accountability, but here’s what I think I’d do if I were superintendent of a school district:

- Calculate a letter grade score for growth and a letter grade score for absolute achievement score.

- Publish the higher of these grades as the letter grade that appears most prominently on the online enrollment system. I would also include the lower letter grade, as well as a bunch of information about school programs and curriculum, on the school’s online profile.

- Allow for government intervention in schools that are in the bottom 5–10 percent for both growth and absolute (you need to perform bad on both).

This type of accountability system gives parent’s good information, avoids the political war of giving low letter grades to schools with high absolute scores, and avoids the error of intervening in schools that have low absolute scores and higher growth scores.

It does give an accountability pass to schools with high absolute scores and low growth, but I view this as OK in that it’s both politically useful and it does reflect the notion that parents really want to get into these schools.

It also still uses test scores as the primary way to evaluate schools. This sits uneasy with me, as I think schooling is about much more than tests, but I haven’t seen any other way to measure schools that feels more reliable. I hope this changes.

I’m not very confident that this is the best system, but I think it’s the best of a bunch of options that all have reasonable drawbacks.

Another hard question would be what to do if local politics did not allow for the creation of a system like this. At some point, if the drumbeat for absolute scores was too much, I’d probably walk away from accountability as a superintendent.

But I’m not sure. If you scan my blog’s history, I’m sure you can find me saying conflicting things about accountability. I’m conflicted about it. But the above reflects my current thinking of what makes for a good accountability system. And as I wrote at the outset, reasonable arguments can be made for everything from no accountability to heavy-handed systems that require testing, give schools letter grades, and intervene in lowest performing schools. Nevertheless, research like NWEA’s recent study is worthwhile and helps shed further light on whether good policies are being implemented well.

Neerav Kingsland is the Managing Director of The City Fund. He first published this essay on his blog, “relinquishment.”

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the authors and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.