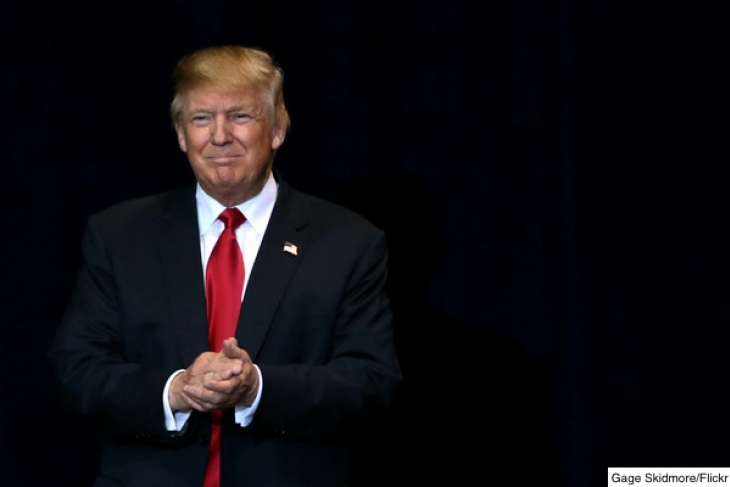

As of Thanksgiving 2016, nobody can forecast what the Trump administration will do—or even try to do—in K–12 education. Practically all he proposed during the campaign was a whopping new federal program to promote school choice. There was also loose talk about “cutting” the Department of Education and about the Common Core State Standards being “a total disaster.” It’s also no secret that, as governor of Indiana, Mike Pence was strongly pro-school choice and allergic to the Common Core (though the Hoosier State wound up with a close facsimile).

There’s not much more to go on today, save to note that Betsy DeVos, a highly accomplished, take-no-prisoners, school-choice advocate, is Trump’s pick for education secretary, and able individuals such as Gerard Robinson and Bill Evers are working on the education department’s “transition team.”

So let’s focus instead on some unsolicited advice to the President-elect as to what his administration’s policy priorities in this domain should (and shouldn’t) be.

Start, please, with the huge fact of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and its implications. When Congress passed and President Obama signed it in December 2015, almost fifteen years after George W. Bush proposed No Child Left Behind, the great bulk of the federal role in K–12 education was all but locked in—locked up, you might even say—for a foreseeable future that is all but certain to outlast the Trump presidency. I can’t imagine the next two Congresses (or probably the two after that) reopening this vast statute, which contains just about everything Uncle Sam does in primary-secondary education save for special education, vocational education, and the research-and-statistics functions housed in the Institute for Education Sciences (IES).

ESSA’s existence—and legislative history—makes it extremely unlikely that Congress will agree to launch any large new school-choice program or to make portable the funds that flow through existing programs to states and districts. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions, tried but failed to muster the votes for a lesser such initiative—and that was with a larger Republican majority in both houses than Trump will face. Secretary DeVos will almost surely come forward with a proposal and choice could likely clear the House of Representatives in some form, but its prospects in the Senate are bleak—and the appetite for even trying to amend ESSA will be faint-to-nonexistent.

ESSA also means that, from Washington’s standpoint, Common Core is now a non-issue. Sure, senior federal officials might try to jawbone states that have stuck with those new academic standards into abandoning them, but the executive branch has no formal leverage. In Chairman Alexander’s words, ESSA “specifically prohibited the U.S. Department of Education from requiring or even incentivizing any state to have Common Core or any other academic standard. That is now entirely a state decision. So the Secretary of Education couldn’t abolish it and he couldn’t require it of states.”

There are, to be sure, innumerable regulatory, budgetary, and implementation issues posed by ESSA, and these are bound to engage the new Education Secretary, although they won’t likely rise to the level of White House attention. Because John King’s team is striving during Obama’s final weeks to promulgate regulations that violate the spirit of ESSA, such as mandating that states issue single summative grades for all schools, revising or withdrawing these will be a matter of some urgency. Important budget decisions must also be made. But that’s about it.

Three other important federal education laws await final Congressional action, and if they don’t get it during the waning weeks of 2016’s “lame duck” session, the new administration will have a shot at influencing them during the 115th Congress. The “Perkins Act”—a source of federal aid to career, technical, and vocational education—needs a major modernization and recently got one in the House but seems to have stalled in the Senate. The reauthorization of IES has neared final passage a couple of times but hasn’t cleared both chambers in quite the same form. And the parts of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that are not permanently authorized (i.e., the lesser parts) are sorely overdue for Congressional attention. In my view, the big parts also need a total makeover—and would be a terrific vehicle for school choice akin to Florida’s McKay Scholarship Program—but everyone in Washington seems allergic to touching special ed, an issue that would challenge even the most politically sure-footed of Presidents.

If Congress doesn’t finalize Perkins and IES, the new team should swiftly weigh in. Trump has hinted at a real interest in “vocational and technical” education—and his business history would seem to incline him that way. He also seems less enamored of the “college for all” mantra. Particularly if the administration simultaneously addressed Perkins and the also-needs-reauthorizing Higher Education Act, the Trumpsters might persuade Congress to do something significant to give the U.S. a robust, rigorous, and respectable alternative to college.

As for IES, wonky as it is, the government’s research, statistics, and assessment work could be far more informative than it now is. Consider, for example, the fact that the National Assessment of Educational Progress reports state-by-state achievement in reading, math, and science for grades four and eight but not grade twelve. What’s with that? And it produces no state-level data on student learning in history, civics, and other key subjects. If states are truly to be re-empowered to shape and run their K–12 education systems, transparency and comparability seem (at least to me) to argue for more reliable external data by which state leaders can see how their schools are faring.

Legislation and bully pulpit aside, the Trump team faces plenty of opportunities on the regulatory and de-regulatory front, not just in sanely implementing programs like ESSA and IDEA without constraining state flexibility but also—especially—in the civil rights realm. There the Education Department Office for Civil Rights (OCR), often teamed up with the Justice Department, has gone wild in pushing schools and districts around, via both formal regulations and menacing “dear colleague” letters, in far-flung realms from student discipline to bathroom access. OCR has long been in the hands of zealots committed both to “progressive” social policies and to such appalling doctrines as “disparate impact” (whereby an even-handed policy or practice is suspect if the results of its application vary by race, gender, whatever). This won’t be an easy omelet to unscramble, especially in today’s hyper-racialized climate of mistrust and even violence, but there’s no part of federal education policy in greater need of redirection—and none that is more subject to unilateral action by the executive branch.

In short, plenty needs doing in the K–12 realm, although it doesn’t much resemble Donald Trump’s campaign talk.

Editor's notes: This article was updated on November 23 after President-elect Donald Trump named Betsy DeVos as his pick for U.S. Secretary of Education.