By Chester E. Finn, Jr.

No, I’m not suggesting that social studies kill people, but the recent emission by the National Council for the Social Studies of “guidance for enhancing the rigor of K–12 civics, economics, geography, and history” does have this in common with the agreement that the U.S. and Russia reached in Geneva on Saturday regarding Syria’s chemical weapons: both are termed “frameworks” and neither will do any good unless many other people do many other things that they are highly unlikely to do.

The Syrians must itemize, declare, and dismantle their chemical weapons. All of them. Fast. Who really thinks that’s going to happen?

And for the College, Career and Civic Life Framework for Social Studies State Standards to have any positive influence on this woebegone realm of the American curriculum, states and districts (and textbook publishers, teachers, etc.) must supply all the content. For this framework is avowedly, even proudly, devoid of all content.

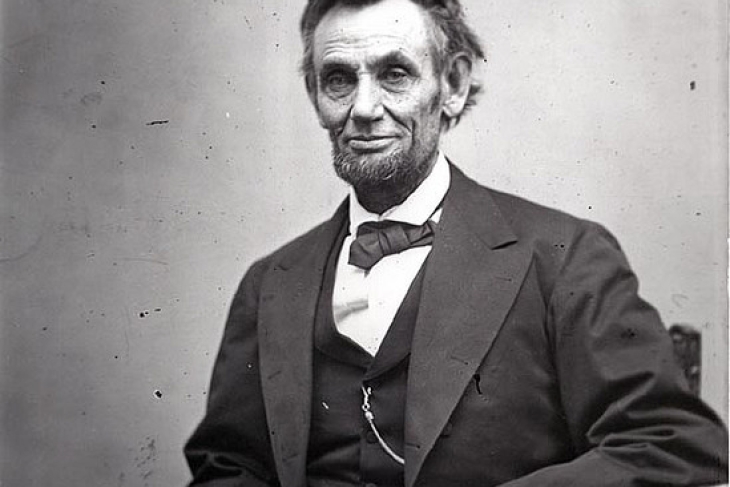

Nowhere in its 108 pages will you find Abraham Lincoln, the Declaration of Independence, Martin Luther King (or Martin Luther), a map of the United States, or the concept of supply and demand. You won’t find anything that you might think children should actually learn about history, geography, civics or economics.

Instead, you will something called an “Inquiry Arc,” defined as “as set of interlocking and mutually supportive ideas that frame the ways students learn social studies content.”

Got that? Here’s an example of how it works. Turn to table 23 on page 49. This has to do with “causation and argumentation” and purports to be part of the inquiry arc as applied to history, in particular to “dimension 2,” dubbed “causation and argumentation.”

By the end of grade 2, “individually and with others,” students will “generate possible reasons for an event or developments in the past.” (That event might be World War I, or it might be the day grandma dropped the turkey on the floor.)

By the end of grade 5, they will “explain probable causes and effects of events and developments.” (Let me tell you what happened after Susie smacked Jamie.)

By the end of grade 8, they will “explain multiple causes and effects of events and developments in the past.” (Actually, she said she hit him for two reasons.)

And by the end of high school, they will “analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.” Now we’ve moved from “explain” to “analyze,” and we’ve added “complex.” But, as throughout the entire document, there is no content whatsoever. No actual history.

Sure, one could build good stuff on this framework. But one could also build trash. Or nothing.

The publication of the “C3” framework (that stands for “college, career, and civic life”) is not, however, a neutral act. It is, in fact, a damaging act for American education. In struggling (on multiple pages) to insist that it is “aligned” with the Common Core state standards for English language arts, it demeans the Common Core and complicates the work of those trying earnestly to implement it. And by enshrining “twenty-first-century skills” within social studies, it puts a further squeeze on actual content and reduces the odds that kids, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, will emerge from school with anything like the knowledge they need to be effective, productive citizens and participants in the nation’s shared culture, civic life, and public discourse.

As Rick Hess wrote,

Most college graduates can’t identify famous phrases from the Gettysburg Address or cite the protections of the Bill of Rights. If our ‘national experts’ can’t bring themselves to come out and just say ‘Kids should know when the Civil War was,’ it’s not clear that an ‘inquiry arc of interlocking and mutually reinforcing elements’ will help kids find out.

But console yourself with this thought: If and when C3 takes over social studies, the chemical-weapons problem will recede in everyone’s mind, for tomorrow’s citizens won’t have a clue where Syria is or what they’re fighting about.