One of the big themes in the Star Wars series is the battle between technology and tradition: the Empire with its Death Star, Imperial Starfleet, and other modern marvels versus the Jedi with their ascetic lifestyles and primitive Force.

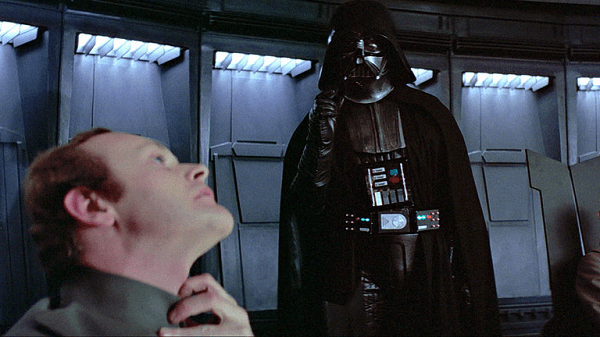

A famous scene in Episode IV captures it perfectly:

Admiral Motti: This station is now the ultimate power in the universe! I suggest we use it!

Darth Vader: Don't be too proud of this technological terror you've constructed. The ability to destroy a planet is insignificant next to the power of the Force.

Admiral Motti: Don't try to frighten us with your sorcerer's ways, Lord Vader. Your sad devotion to that ancient religion has not helped you conjure up the stolen data tapes, or given you clairvoyance enough to find the rebels' hidden fort...

(Vader makes a pinching motion; Motti starts choking.)

Darth Vader: I find your lack of faith disturbing.

Han Solo, condescending to the lightsaber-wielding Luke, later scoffs, “Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid.”

The gist is that the advocates of modernity can be snootily proud of their creations and dismissive of the backward tools of older generations.

You can see this play out in education, with the Young Turks of reform offering up dazzling new solutions and looking down on the old guard and all of their mistakes.

Think of all the times reformers have mocked “the factory model” of schooling, voiced exasperation that classrooms look the same today as they did one hundred years ago, and lamented that the school calendar still reflects an agrarian economy. Why, wonders the confident reformer, can’t these old-timers just stand down so we can make progress?

A little more than a year ago, I wrote about education reform’s fondness for the new and different:

We have NewSchools Venture Fund, New Schools for New Orleans, and New Schools for Baton Rouge. We have New Classrooms, New Profit, and New Visions for Public Schools. We have New Leaders, Knewton, and the New Teacher Center. Before rebranding as “TNTP,” it was The New Teacher Project.

We have variations on this theme—“new” by other names.

Constructing a new future with EdBuild; exploring, settling, and cultivating new lands with Education Pioneers and “greenfield schooling”; beginning anew with Startup: Education, Starting Fresh, Innovate Public Schools, Innovative Schools, and Policy Innovators in Education.

And, as if we hadn’t sufficiently signaled our Bastille-storming, we have Parent Revolution, Revolution Foods, Revolution Learning, and Revolution Prep.

Like the Empire and many, many, many other reform movements, today’s education reform also seems to place an outsized faith in technology. We like to see ourselves as enlightened and armed with advanced implements—so much the better to distinguish ourselves from an unscientific past.

We have blended and online learning, all sorts of devices, all-encompassing longitudinal data systems, and spellbinding algorithms. The implication, of course, is that the challenges we face are primarily technical in nature. If only our hidebound schools could appreciate modern sophistication, we could slough off our ancient ways.

I was reminded of this recently when, during a meeting, a very accomplished professional compared the development of cutting-edge teacher evaluation systems to the development of the iPhone—a feat of scientific progress that could only be achieved through technical know-how.

In my view, understanding human institutions and practices as primarily technical matters can be treacherous. It suggests that disagreements aren’t about clashing values or different priorities, but about forward versus backward—or, still worse, right versus wrong. It replaces deliberative democracy and all of its messy but vitalizing debates with the sterility and paternalism of technocracy. It sees old practices not as evolved but as primitive. It tells old-way practitioners that they’ve been eclipsed.

I believe that reformers should think and talk a whole lot more about the many indispensable parts of old-fashioned schooling that should be preserved. That might include traditional but out-of-vogue approaches to instruction and curriculum; a reliance on adult-to-child interactions instead of digital ones; local, democratic governance; the explicit transmission of a community’s history and values; and community and parent-based assessments of schools instead of solely empirical metrics.

Now, I’m neither a reactionary nor a Luddite. Like Jefferson, I believe that “our laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.” Our kids are obviously the beneficiaries of lots of reforms that were once considered avant-garde—our use of nonprofit school operators, our understanding of brain development, our expectation of universal college and career readiness, etc.

Neither would I argue that all that’s old glitters like gold. Like us, our predecessors were far from perfect. We can’t forget that the ancient Force, for all of its good, also had a dark side.

My point is only that there are often very good reasons why defenders of the current order find reformers’ lack of faith, well, disturbing.