Editor's note: This is the fifth entry in our forum on charter school discipline practices. Earlier posts can be found here, here, here, and here.

At the National Charter Schools Conference in June, Secretary of Education John King challenged charter schools to rethink their approach to discipline. His remarks were measured and appropriate in their intent, but they were based on two sets of evidence—one compelling and one problematic.

King spoke about his personal experience as a co-founder of Roxbury Prep, a very successful Boston charter school. The school’s approach includes the use of strict discipline practices that resulted in a 40 percent suspension rate in 2014. Roxbury Prep has started to rethink its methods, but King acknowledged it has not done so fast enough, and he urged charter leaders to “commit to accelerate exactly this kind of work.”

King’s experience grounds his comments in the specifics of a school setting, as well as the particular procedures common in many “no-excuses” charter schools. He also said in his remarks that there should not be any “hard and fast rules or directives” to govern charter discipline, ostensibly because context is key to managing discipline. So far, so good.

However, King used a second set of evidence, one that was almost entirely context-free, to reify the popular narrative that charters have a discipline problem. “Not all of the criticism has been fair or accurate,” he said. “But as a whole, it is true that charter schools suspend a higher percentage of their students than do district schools.”

The truth about charter suspension rates is more complicated than that. King’s statement was based on the department’s Civil Rights Data Collection. When those data are used to compare all traditional public schools (TPSs) to all charters, the suspension rates are indeed higher for charters. But the comparisons at the heart of such stories, and of King’s statement, are bogus because so many TPSs are not comparable to charters. TPSs are ubiquitous, whereas charters are more concentrated in urban areas and serve very different student populations. Given these glaring differences, researchers have to make some effort to identify comparable TPSs.

In a forthcoming study, I compare the suspension rates of brick-and-mortar charter schools across the nation to those of their five nearest traditional public school peers. This approach allows me to compare discipline data in charter schools to the TPSs that their students might otherwise attend.

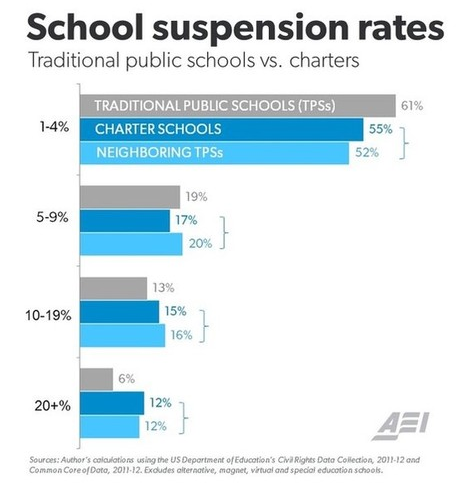

The figure below compares charter suspension rates (in dark blue) to the rates for all TPSs (in gray) and shows that charter rates are indeed higher. However, when compared to their neighboring TPSs (in light blue), the gap essentially disappears. In fact, compared to neighboring TPSs, discipline at charter schools appears slightly lower.

(It is important to note that this figure excludes schools that reported no suspensions because of the possibility that these are data reporting errors. The contrast showing that charters suspend less would be more pronounced if these schools were included, since a higher proportion of charters than TPSs reported zero suspensions.)

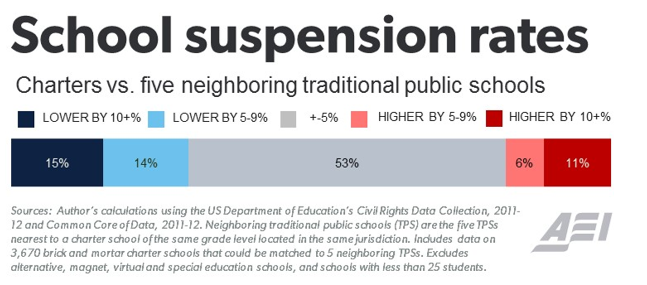

But looking at averages only tells part of the story. It also matters how one compares charters to their neighbors. Charters are not a uniform group; some have low suspension rates and more lenient disciplinary approaches, while others have higher rates and are stricter. Averages can therefore hide as well as reveal patterns. The second chart looks at the distribution of differences between each charter’s suspension rate and the average of their five neighboring TPSs. This figure goes beyond averages to show how often and by how much charters’ suspension rates differ from their neighbors’.

A little more than half of charters (in gray) feature out-of-school suspension rates within five points of their neighboring TPSs. The sections in red show the proportion of charters with higher rates than their neighboring TPSs. About 11 percent (in dark red) feature suspension rates ten or more percentage points higher, and 6 percent (in light red) demonstrate higher rates by 5–9 percentage points.

The blue sections indicate that a much larger percentage of charters have lower suspension rates than their neighboring TPSs. Fifteen percent of charters feature lower suspension rates than their neighbors by ten or more points (dark blue), and 14 percent have rates 5–9 points lower (light blue).

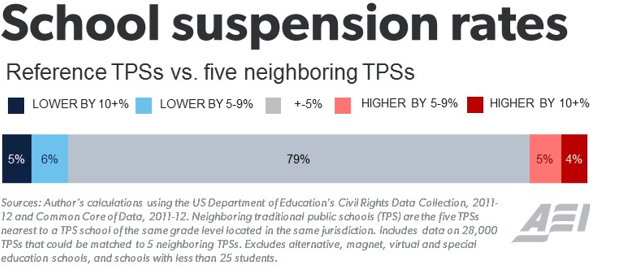

To provide a frame of reference for these differences, I also used the identical matching method for over twenty-eight thousand TPSs (“reference TPSs”) and compared them to their five neighbors. The third figure shows that suspension rates for reference TPSs are much more similar to their neighboring schools, with roughly 5 percent of TPSs having higher and lower suspension rates. The contrast shows that charters demonstrate both disproportionately higher and lower relative suspension rates compared to reference TPSs.

These findings certainly indicate that some charters have markedly higher suspension rates than TPSs. Such schools may well deserve attention from authorizers or other authorities, and they may need to rethink their approach to discipline. However, about 29 percent of charters have lower suspension rates, a much larger percentage than have higher rates (17 percent). These results strongly suggest that the common perception—that charter schools suspend students more frequently than TPSs—is backwards.

King challenged charter leaders not to “get caught up in battles about whether charters are a little better or a little worse than average on discipline” and instead “focus on innovating to lead the way for the sake of our students." I agree that it’s worth rethinking student discipline and that some charter schools deserve close attention on that score.

King’s statements—on top of the fact that he chose to focus on discipline in his remarks to a charter school conference—unfortunately support the mistaken notion that charter schools have a particular problem with suspensions. In a vacuum, those implications might be innocuous. But in today’s highly politicized debates about charters, they add fuel to an already-hot fire. As the secretary of education, King has to get the basics right or risk doing a disservice to the much greater proportion of charters that are already leading the way on school suspensions.

Nat Malkus is a research fellow in education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.