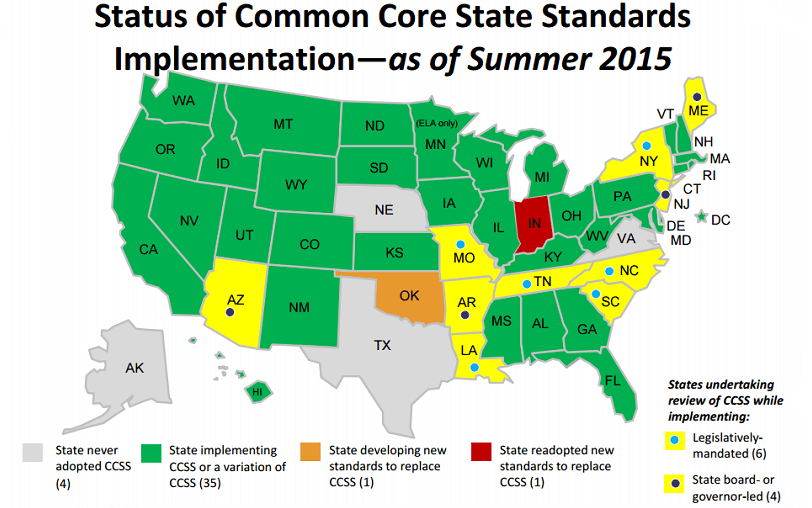

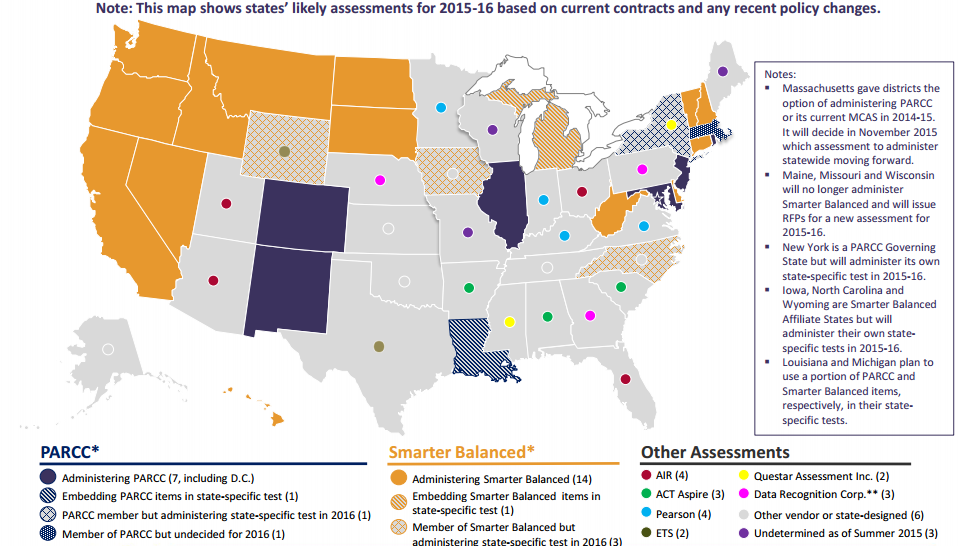

As we move into the 2015–16 school year, the standards and assessments landscape is continuing to shift. State legislative and executive actions over the past year have resulted in changes to how, when, and—in some cases—if districts and schools will implement Common Core standards and aligned assessments. Education First’s Common Core and Assessments Status Maps detail these changes, looking back over the last year and forward to the next.

The good news: An overwhelming majority of states (forty-four, plus the District of Columbia) will continue to implement Common Core next year—this despite dozens of bills in nearly thirty states to delay or repeal it. Policymakers are sticking with higher expectations for all kids because educators, parents, and students tell them that the standards are improving instruction in classrooms across the nation. Yes, ten states are reviewing their standards (a best practice that was in place well before Common Core); but as we know from Indiana’s experience, most of them will continue with either the Core or standards that closely resemble it. States from Louisiana to New Jersey are finding that their reviews help them build on the standards rather than tearing them apart. Only Oklahoma is determined to go it alone. With so much of the country sticking with the standards, “follow-through” is the new watchword.

A number of states' assessment plans are likely to change in the new school year. Both assessment consortia have lost members, yet almost half of the states (twenty-two, as well as D.C.) are still using either PARCC or Smarter Balanced materials in 2015–2016. The consortia tests, as well as those developed by individual states to measure Common Core, aren’t just more difficult for the sake of it. They are superior tests designed to measure how prepared all students are for expectations of the next grade level or education beyond high school. Early test results in Idaho, Oregon, Washington, West Virginia and other states show that while there is considerable room for improvement to get all students college- and career-ready, students performed better than expected this first year.

But it’s a lot easier to sacrifice tests to political pressures than standards. We predict that more states will seek out their own assessments. The challenge as states follow through on high-quality assessments is to seek both quality and comparability. Will we sacrifice the original promise of the consortia—that states can both use better assessments and compare results across state (and college) lines? Let’s not forget that the old tests we’re replacing didn’t measure up (as Fordham’s research shows). Families and communities in every state deserve to know what it takes to succeed after high school and whether students are on track for college and career readiness. High-quality, comparable assessments are essential.

Joe Anderson and Kelly James are an analyst and principal at Education First.