In a new NEPC policy memo, Duke public policy professor Helen Ladd argues that charter schools “undermine” good education policymaking by making it needlessly complex.

More specifically, according to Ladd, charters “disrupt” four core goals of American education policy: “establishing coherent systems of schools,” “appropriate accountability for the use of public funds,” “limiting racial segregation and isolation,” and “attending to child poverty and disadvantage.”

That’s a lot to tackle, so what follows isn’t meant to be comprehensive—but for simplicity’s sake, I am using Ladd’s “goals” to structure my response.

Goal 1: “Establishing coherent systems of schools”

It might surprise readers in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, and any number of other places to learn that their nation’s school systems are incoherent. Yet that is the logical implication of Ladd’s first line of attack, the upshot of which is that a system in which public dollars can follow students to schools not run by the government creates unworkable complexity. Either that, or she’s claiming there’s something unique about the United States that argues against the creation of a such a system here—though she never says as much, and it’s difficult to see why that would be the case.

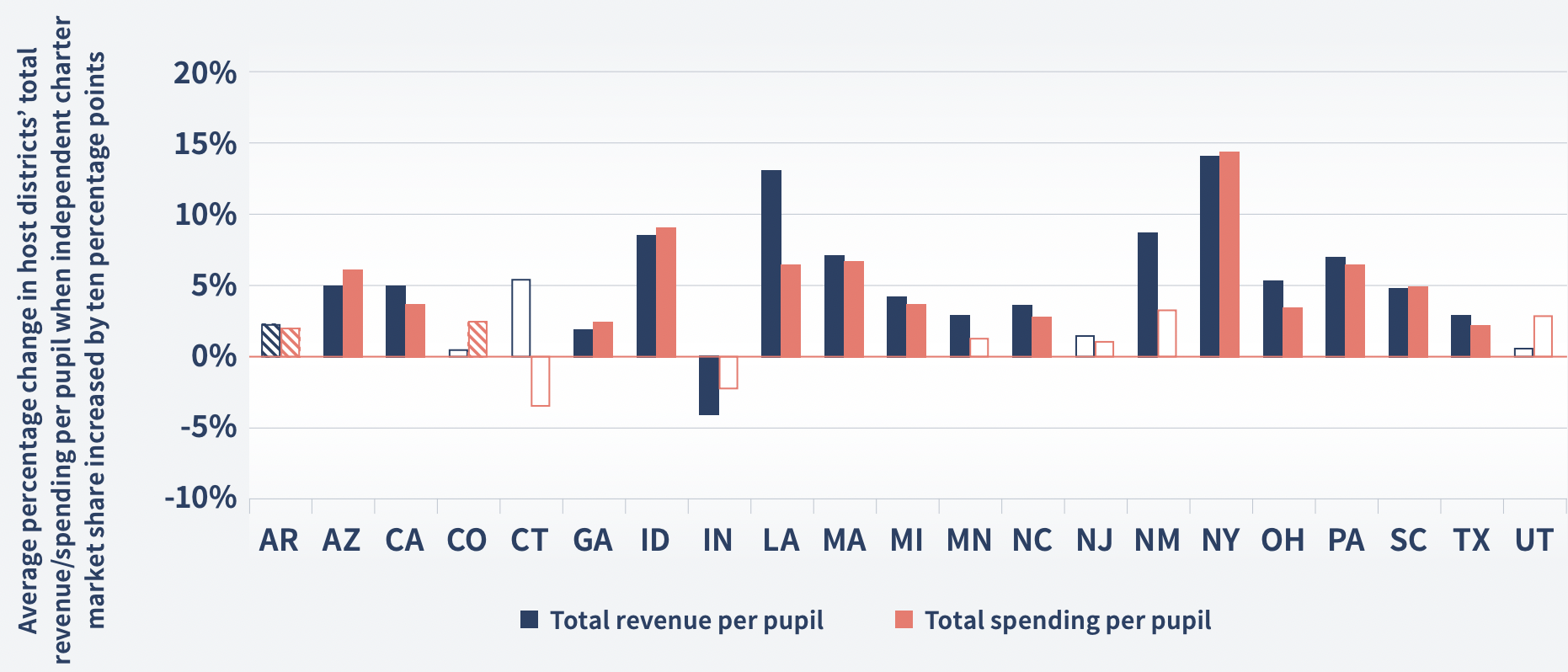

Veterans of the charter school movement will recognize many of Ladd’s arguments. For example, she asserts that “given public funding follows students to charter schools on a per-pupil basis, the outflow of students to charters means that the local districts will be financially worse off.” The first clause of that sentence deserves at least three Pinocchios, given the well-documented exclusion of many charters from many local funding sources. But even if it were accurate, the conclusion that districts are “financially worse off” wouldn’t follow. After all, most states provide at least temporary relief when a district’s enrollment declines, and some even explicitly compensate them for charter-driven enrollment losses. In other words, simple arithmetic implies that many “host” districts get more funding per pupil when some of “their” pupils enroll in charters, as a recent Fordham study confirmed.

Figure 1. In most states, higher independent charter market share was associated with a significant increase in host districts’ total revenue and spending per pupil

Note: Hollow bars indicate nonsignificance, filled bars statistical significance at the p<0.05 level, and striped bars at the <0.1 level.

Source: Mark Weber, “Robbers or Victims? Charter Schools and District Finances,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (February 2021).

Later, Ladd claims that “in practice, many charter schools are operated by charter management organizations or by management chains operating many schools which often have no ties to the local community” [emphasis added]. But if she’s talking about the leaders of these networks, then the same could also be said of many state and local administrators (not to mention union leaders). And if she’s talking about principals and teachers, then the quoted sentence is a wild exaggeration.

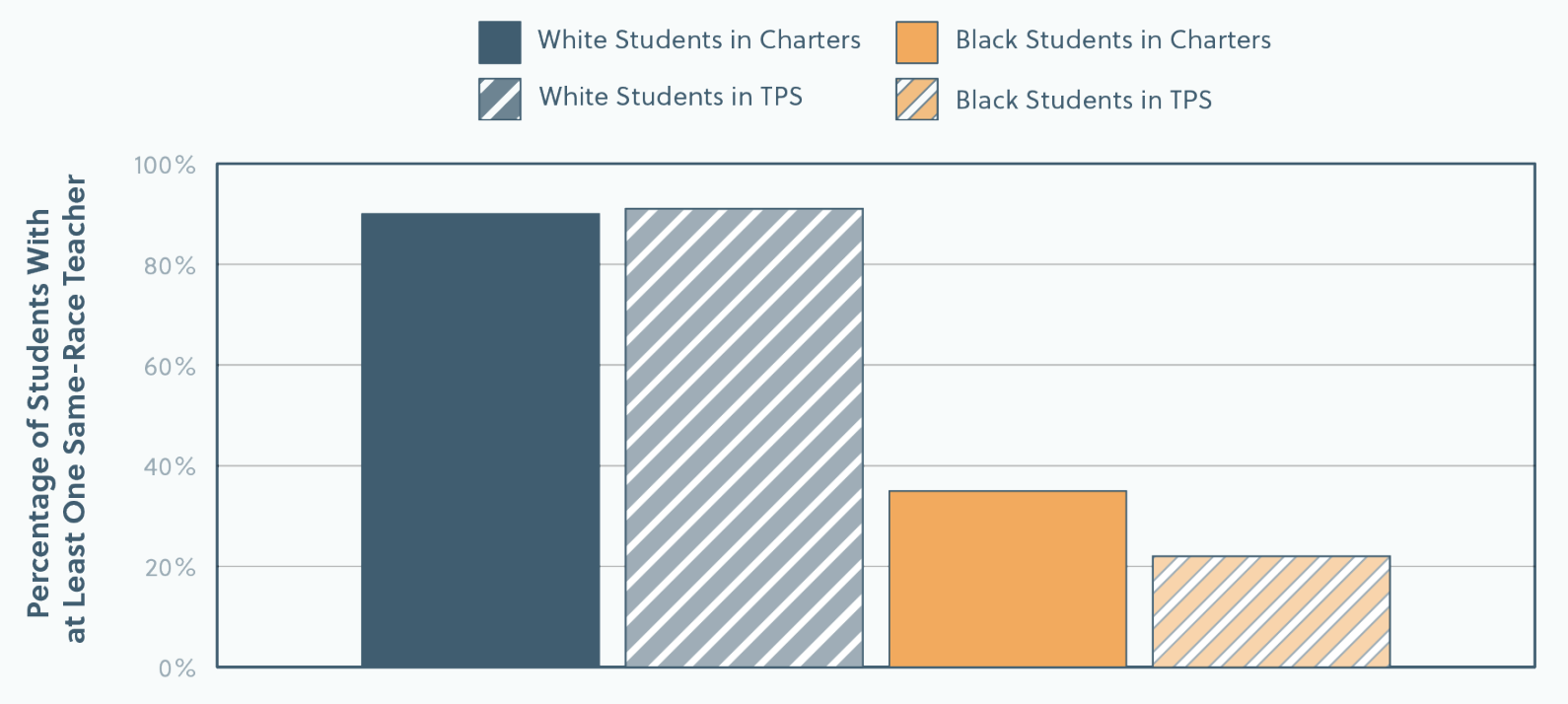

For the record, charter schools that belong to larger networks hire lots of teachers from “the local community,” in addition to some Teach For America types and other imports. And of course, regardless of how that community is defined, traditional public schools don’t perfectly reflect it either. For example, a recent Fordham study found that Black students in North Carolina were significantly less likely to have a Black teacher if they enrolled in a traditional public school, as opposed to a charter.

Figure 2. Relative to their Black peers in traditional public schools, Black students in charter schools are significantly more likely to have same-race teachers

Source: Seth Gershenson, “Student-Teacher Race Match in Charter and Traditional Public Schools,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (June 2019).

Goal 2: “Appropriate accountability for the use of public funds”

Like the previous section, this one has a little bit of everything, from complaints about the rate at which charters close their doors to demands for greater financial transparency. Yet in general, Ladd’s arguments in this realm fail to engage with (much less refute) the obvious counterarguments.

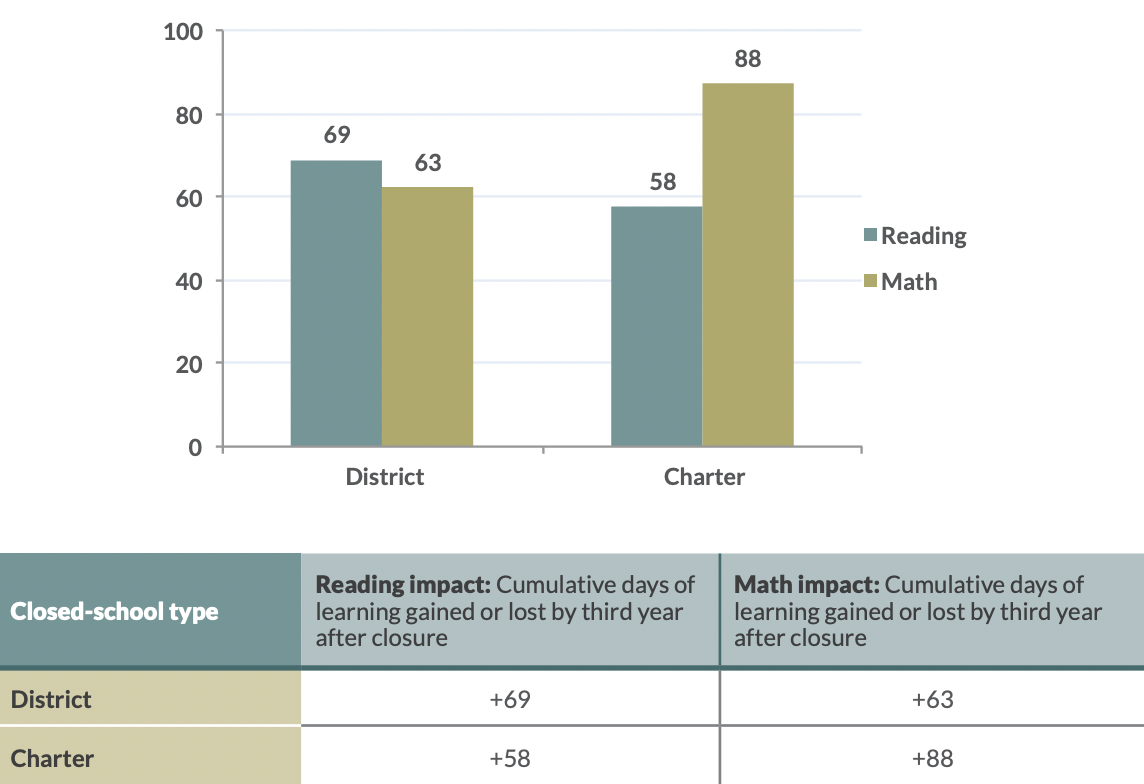

Take school closure. Ladd treats it as manifestly undesirable, but lots of research suggests that displaced students benefit when they move to higher-performing schools. So, at a minimum, any argument against a school system that envisions the periodic closure of low-performers needs to reckon with that finding (as well as the deeper truth, which is that closing a bad school makes it more likely that subsequent cohorts of students will attend a better one).

Figure 3. Impact of closure on displaced students who landed in higher-quality schools, measured as cumulative learning gains by third year after closure

Source: Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu, “School Closures and Student Achievement: An Analysis of Ohio’s Urban District and Charter Schools,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (April 2015).

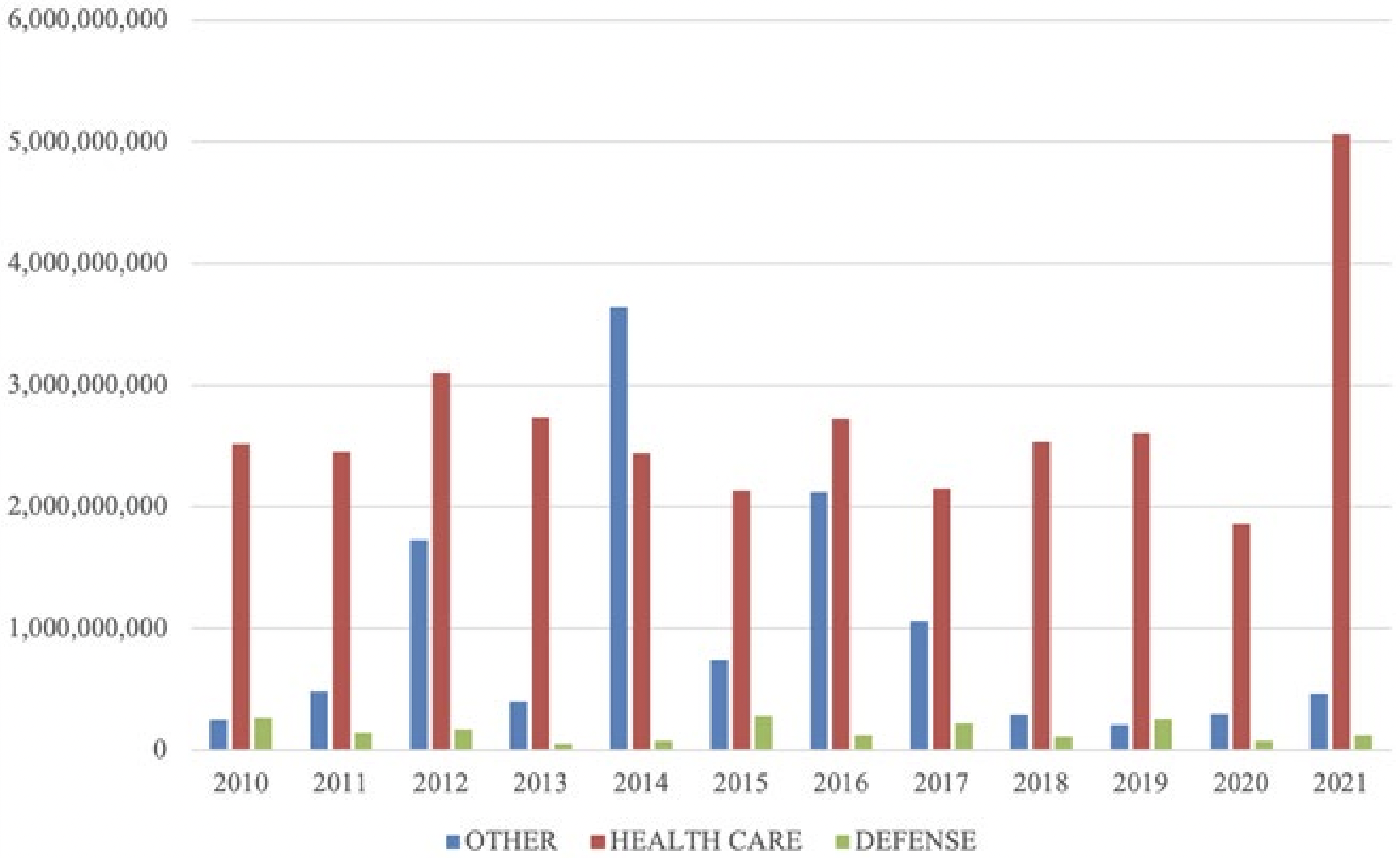

Or consider the similarly thorny question of financial oversight. Ladd asserts that “because charter schools are run by private organizations, they are not typically subject to the financial transparency requirements of government entities.” But of course, the same could be said of the for-profit and non-profit organizations that government contracts with in other sectors, from healthcare to housing and most definitely including traditional public-school systems. So is the point that those organizations should also face greater scrutiny? And if not, then what is the rationale for singling out their counterparts in the charter sector?

To be clear, bona fide fraud can and should be prosecuted. But it’s also a fact of life. For example, below is the U.S. Department of Justice’s account of the monies it has recovered in settlements and judgments from civil cases involving fraud and false claims against the government over the past twelve years.

Figure 4. False Claims Act recoveries by industry, 2010–2021

Source: “2021 Year-End False Claims Act Update,” Gibson Dunn, retrieved December 7, 2022. (Figure cites: “Fraud Statistics – Overview,” Department of Justice (February 1, 2022)).

Per the chart, the federal government loses billions of dollars to healthcare fraud every year. Yet almost nobody seems to think the Department of Health and Human Services or local health departments should run America’s hospitals and pharmacies.

Goal 3: “Limiting racial segregation and isolation”

This part of Ladd’s complaint has the most going for it. After all, the most comprehensive analysis to date found that charters do marginally increase racial segregation—at least at the school level—as does some of Ladd’s own research. So if there’s an intellectually honest argument against school choice in the United States, I suppose this is it.

Still, it’s worth bearing a few points in mind.

First, there is a huge moral difference between de facto and de jure segregation, especially when the former is partly attributable to the choices of Black and Brown families, as it is in charters.

Second, the current district system is already highly segregated at the school level, and even traditional public schools that are diverse on paper can feel segregated in practice.

Third, the fact that the typical district system links the education and housing markets tends to exacerbate residential segregation, which also seems to be harmful to racial minorities. So any policy that breaks this link could do some good on the housing front.

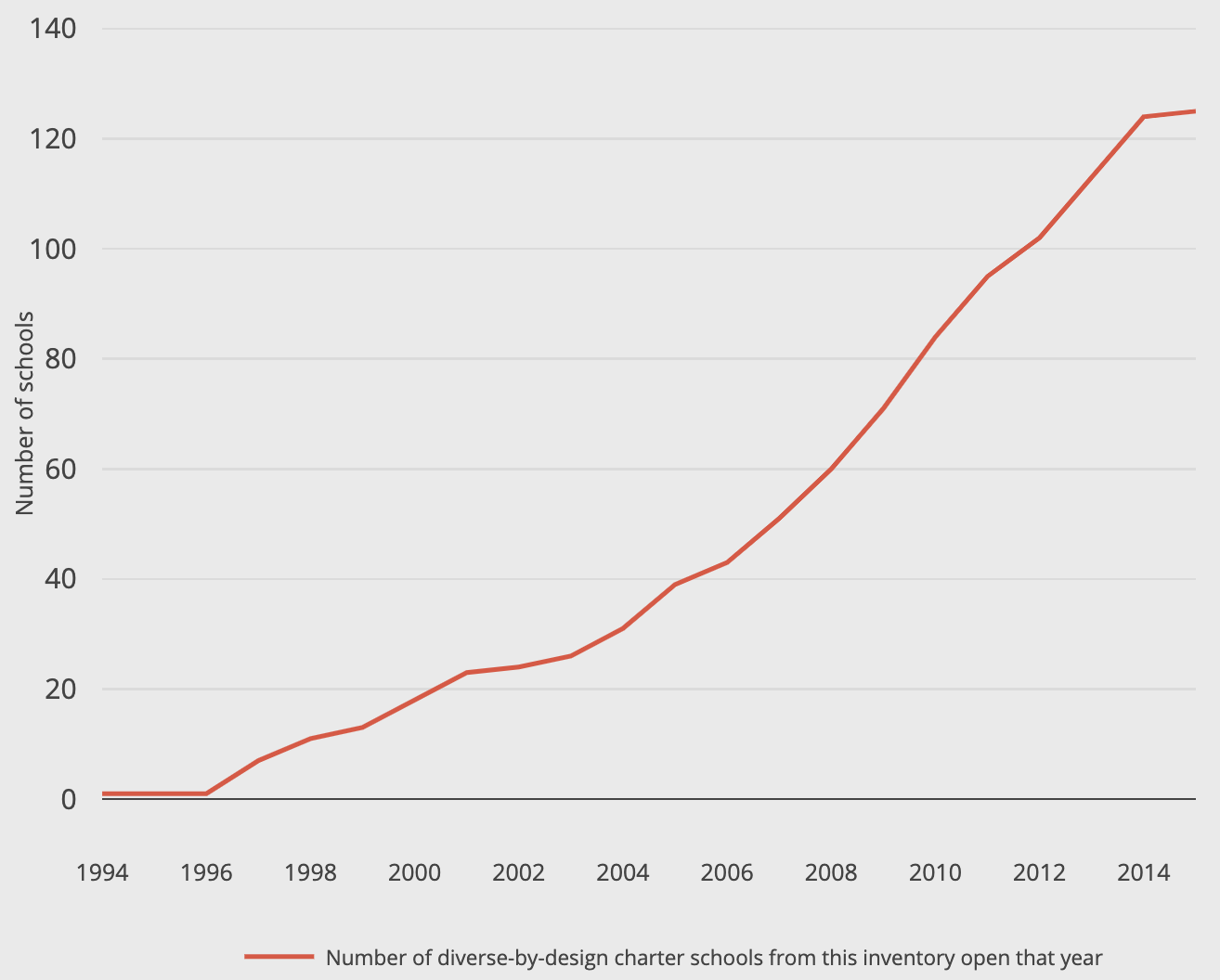

And finally, a small but growing percentage of charter schools are diverse by design, meaning they use some combination of strategic location, targeted recruitment, and “weighted lotteries” that prioritize economically disadvantaged kids to create a desirable mix of students.

Figure 5. Growth of intentionally diverse charters1994–2014

Note: To my knowledge, this is the most recent version of this figure, although the Diverse Charter Schools Coalition currently claims 227 schools as members.

Source: Halley Potter and Kimberly Quick, “Diverse-by-Design Charter Schools,” The Century Foundation (May 15, 2018) (figure cites the National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics).

In my opinion, both the charter school movement and the country would benefit from the creation of more such schools, which haven’t received the kind of attention and investment that KIPP and other networks have benefitted from, despite a decent track record. But of course, parents can’t be forced to apply to racially and socioeconomically diverse schools. So when push comes to shove, it’s unlikely that charters or other forms of school choice can actually solve the larger problem. But then, neither has the rest of American public education in the nearly three-quarters of a century since Brown v. Board of Education.

Goal 4: “Attending to child poverty and disadvantage.”

Here’s where Ladd’s memo exhibits the most transparent and (frankly) indefensible bias. To wit:

Conceivably… the most effective charters could be the ones in urban areas serving disadvantaged students who otherwise would have attended low-quality neighborhood schools. Indeed, careful empirical studies of charter schools in the cities of Boston, Newark, and New York provide some support for that possibility. Moreover, a 2015 study of charter schools in urban regions also painted a more positive picture for urban charter schools than for those in other areas. That study made it clear, however, that despite their successes in some cities, charter schools in many urban areas were no more effective than the district schools in those areas [emphasis added].

Actually, the 2015 study referenced in the passage found that charters significantly outperformed traditional public schools in reading in twenty-six cities (i.e., “some”), while performing no better or significantly worse in fifteen cities (i.e., “many”). In math, charters significantly outperformed traditional public schools in twenty-three cities, while performing similarly in eight and significantly worse in ten.

Furthermore, the very same study found particularly large gains for poor and/or traditionally disadvantaged students who attended charters. Specifically:

Across all urban regions, Black students in poverty receive the equivalent of 59 days of additional learning in math and 44 days of additional learning in reading compared to their peers in TPS. Hispanic students in poverty experience the equivalent of 48 days of additional learning in math and 25 days of additional learning in reading in charter schools relative to their peers in TPS.

Seems like a pretty defensible way to attend to “child poverty and disadvantage.” And that’s before we get to all the other research on charter performance that Ladd doesn’t cite. Or the fact that said performance continues to improve. Or the overwhelming likelihood that charters would perform even better if they were more equitably funded. Or the ever-growing literature on their competitive effects, which suggests that their presence also tends to boost achievement in traditional public schools.

Somehow, there wasn’t space for any of those points in a twenty-one-page memo on charters’ relationship to “good education policymaking.” But that’s why we have opportunities to respond.