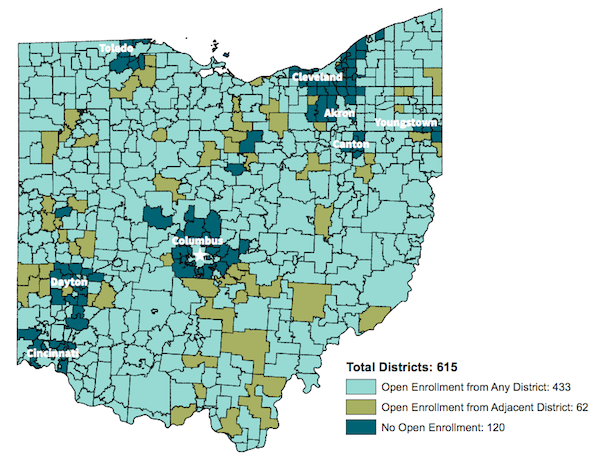

The Fordham Institute has released an important new study on open enrollment in Ohio. Figure 1’s dark blue areas show districts not participating in open enrollment, and they just happen to be leafy suburban districts that are both higher income with predominantly white student bodies and near large urban districts with many students, who are neither of these things. Feel free to reference this the next time someone claims that public schools “take everyone.”

Figure 1. Ohio school districts by open-enrollment status: 2013–14 school year

Many moons ago, I wrote a study for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy about the interaction between charter schools and open enrollment in Michigan. I found a very clear pattern among some of the suburban districts whereby charter schools provided the incentive for early open enrollment participants to opt-in. After one district began taking open enrollment transfers and some additional charters opened, it created an incentive for additional nearby districts to opt in—they were now losing students to both charters and the opted-in district. Through this mechanism, the highly economically and racially segregated walled-off district system began to collapse.

Not every domino fell, however. I interviewed a superintendent of a fancy inner-ring suburb who related that his district saw their competitors as elite private schools, not charter schools. When I asked him why his district chose not to participate in open enrollment, he told me something very close to: “I think historically the feeling around here is that we have a good thing going, so they want to keep the unwashed masses out.”

Contrast this as well with Scottsdale Unified in Arizona, which is built for 38,000 students and educates 25,000 students, 4,000 of whom transferred into a Scottsdale Unified school through open enrollment. Four thousand transfer students would rank Scottsdale Unified as the ninth largest CMO in Arizona, and they are far from the only district participating in open enrollment in a big way. Why is Scottsdale willing to participate unlike those fancy Ohio districts? They have 9,000 kids living within their boundaries attending charter and private schools with the assistance of private choice programs.

Why haven’t choice programs torn down the Berlin Walls around suburban Ohio districts? Sadly, it’s because they have been overly focused on urban areas. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools’ Data Dashboard shows that 72.6 percent of Ohio charter schools operated in urban areas. The voucher programs likewise started in Cleveland and then expanded out to include failing schools (and children with disabilities statewide). More recently, a broader voucher program has begun the process of phasing in slowly on a means-tested basis, but the combination of adding a single grade per year and means testing promises to unlock a very modest number of walled-off suburban seats.

These programs have benefits, but they will not provide an incentive for fancy suburban districts to participate in open enrollment any time soon. Informal conversations I have had with Ohio folks related to me that Ohio suburban and rural dwellers—a.k.a. the people who elect the legislative majorities—tend to look at charter schools as a bit of a “Brand Ech” thing for inner-city kids. Rest assured that the thousands of Scottsdale moms sitting on BASIS and Great Hearts charter school waitlists do not view charters as “Brand Ech.” Likewise these folks probably see themselves as paying most of the state of Ohio’s bills through their taxes and just might come to wonder why the state’s voucher programs seem so determined to do so little for their kids and communities.

A serious strategic error of the opening act of the parental choice movement was to look out to places like Lakewood, Ohio, or Scottsdale, Arizona, and say “those people already have choice.” This point of view is both seriously self-defeating in terms of developing sustaining coalitions, and it also fails to appreciate the dynamic interactions between choice programs. Arizona’s choice policies include everyone and have created a virtuous cycle whereby fancy districts compete with charter and private school options for enrollment. This leads to a brutal crucible for new charter schools in Arizona in which parents quickly shut many down because they have plenty of other options. Educators open lots of schools and parents close lots—leading to Arizona’s world-class charter NAEP scores. Indeed, Arizona leads the nation in statewide cohort NAEP gains since 2009, which was more or less mathematically inevitable once this process got rolling. Ohio not so much.

I’m open to challenge from any of my Ohio friends and anyone else. But Ohio’s choice programs sure look to be mired in an urban quagmire, and they need the leafy suburbs to play in order to win. The state’s current policies haven’t unlocked Ohio’s Scottsdale Unified equivalents, and they likely never will. The National Association of Charter School Authorizer put Ohio’s revised charter school law in its top ten, but allow me to pull up a couch and heat up some popcorn for the next few years as charters lawyer up, parents resist arbitrary bureaucratic closures, and the rate of new schools opening goes glacial.

Competition is by far the best method of quality control, and bringing the leafy suburban districts into the melee is crucial if you are in the urban fight to win. The districts that are currently largely untouched by charter-and-private-choice overlap are those not participating in open enrollment. Regulating urban charters is not going to make your suburban districts into de facto charter management organizations. This isn’t hard to figure out. Although it’s counterintuitive to many folks, if states and districts want to secure improved education options for the poor, they need to include everyone.

Matthew Ladner is a Senior Research Fellow at the Charles Koch Institute

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.