Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series. Part I urges readers to "listen more, empathize more, and demonize less" in these divisive times.

After the election, I shared my thoughts about how we might achieve a truce in America’s roiling culture wars. In short, I suggested a simple rule: Empathize, don’t demonize.

How might we apply that rule to the culture wars that stalk our corner of the world in education policy?

By culture wars in ed-policy, I mean those disputes that go beyond traditional interest-group politics, such as teachers unions fighting the expansion of non-union charter schools. Instead I’m referring, for example, to the 1619 versus 1776 debate over how to teach the story of our nation’s history, or to controversies about accommodations for transgender students.

Consider the issue of racial disparities in school discipline—a debate in which I have played the role of partisan. There, I now see, I could have done more to lower the temperature and find common ground.

—

For more than five years, I’ve been writing about the discipline issue, ever since the Obama administration released its much-discussed guidance on discipline, which threatened civil rights investigations into any districts with data showing racial disparities in suspensions or expulsions. I have expressed strong concerns about that guidance ever since, which I will get to in a moment, but I always try to preface my arguments with an honest acknowledgment that we absolutely need to take racial discrimination seriously, including in how schools mete out punishment for misbehavior. And I’ve always agreed that the federal Office for Civil Rights has a clear role to play in responding to any complaints of racial bias or discrimination, including those related to discipline.

Still, I understand now that I did not fully empathize with my colleagues who support significant reductions in suspensions and expulsions, especially for kids of color. That’s because I did not completely understand where they were coming from, which I now believe is from a commitment to ending mass incarceration in this country.

I could have done more to try to understand the pain, the real anguish that so many people experience as a result of that system, especially African Americans.

What must it be like to have such a significant portion of your community behind bars, or in fear of the police, or shackled by criminal records?

A few weeks ago, NPR ran a segment on the impact of neighborhood police violence on pregnant women. Yuki Noguchi interviewed a Black woman, Raven Cain, about being pregnant, after multiple miscarriages, just as George Floyd was murdered around the corner from her parents’ home.

CAIN: You know, during that time, it was constant sirens. Then they were saying that the KKK was supposedly in town, and it’s just stressful. It’s like—and then you’re trying to carry a life, and then you’re thinking about them being a Black person in this world and the things that they might encounter.

NOGUCHI: Cain tried to distract herself by hosting a family party to reveal she was having a girl.

CAIN: My dad was just jumping up and down. Like, he was so happy. He said he went in the garage and cried a little bit.

NOGUCHI: Cried partly out of relief—he told her the world wasn’t safe for Black boys.

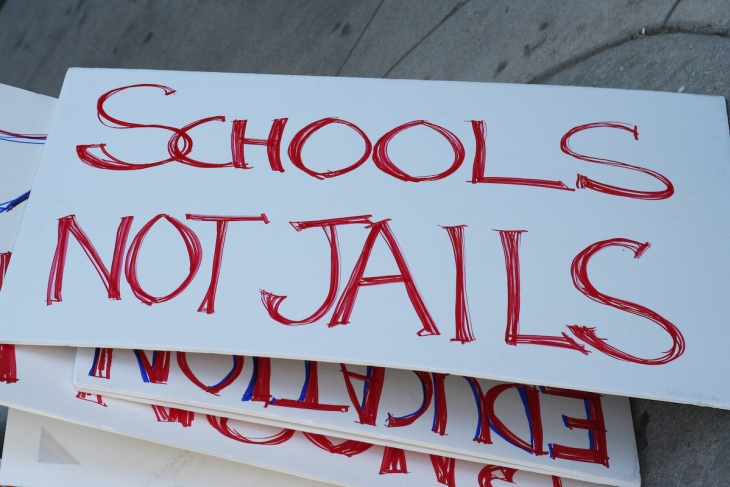

Although improving student outcomes is an important goal for almost everyone in education, for many of our colleagues, reducing the population of Americans behind bars is even more important. And a key step in doing that, they believe, is disrupting the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

I wish I had done more to state clearly that I wholeheartedly agree with this objective, and that we need to do everything we can to keep young people off the pathway to prison. Of course we need to keep our communities safe, but it is a tragedy and a national embarrassment that we have resorted to locking up so many of our fellow citizens, destroying families and livelihoods.

I wish I would have stated unequivocally that, yes, schools absolutely have a role to play in helping to solve this problem.

First and foremost, they can make sure that kids learn to read, given how much we know about the relationship between illiteracy and involvement in the criminal justice system. As students get older, schools must also help them get ready for success in postsecondary education and/or the workplace—to get them on the school-to-upward-mobility pathway.

But most critically, schools, from the earliest age, can help all young people learn how to control their emotions, and their behavior, so as to stay out of trouble and find success cooperating with others. That can be particularly challenging for children growing up in poverty, given the horrific challenges many face at home, from violent neighborhoods to lead poisoning to food insecurity and so much else. And when children do struggle to behave, and they break the rules, or engage in anti-social or even violent behavior, schools should try harder to help them meet behavioral expectations rather than give up on them and “put them out.” In many cases, mental health supports are key.

About all of this I think we can all agree.

But now we get to the hard part. What to do when this all fails? When student misbehavior is dangerous, or chronic, and children aren’t responding to interventions?

Here, I would ask discipline reform advocates to show some empathy for those of us on the other side. We are not happy about suspending or expelling students. But schools that don’t have and enforce clear discipline codes will become unruly and unsafe. That’s not good for students who misbehave, and it is certainly not good for their peers who are studying and trying to learn. Given the nature of our segregated school system, when we are talking about children of color who are misbehaving, we should acknowledge that the preponderance of their peers who suffer the consequences of lost learning time are also children of color.

Many of us discipline-reform skeptics are especially concerned that some of the best- performing high-poverty schools in the country—especially those in high-flying charter networks like KIPP and Achievement First—are facing enormous pressure to ease their behavior standards in ways that may leave them unsafe or disorderly. And that would be a terrible tragedy, given how successful such schools have been in helping their students, almost all of whom are Black or Brown, achieve incredible academic and life success.

To be sure, there are genuine and earnest disagreements between discipline reform proponents and opponents. There are fundamental differences in how these camps would handle the trade-offs between order and safety on the one hand, and the potentially negative impacts of suspensions and expulsions on the other. We also tend to disagree on the best ways to help schools get better at balancing these trade-offs and whether the threat of civil rights investigations is an effective tool for doing so.

But I hope I have demonstrated that it is possible to lower the temperature around a contentious and high-stakes debate by introducing empathy and nuance into the conversation.

If we can reach the point where we acknowledge that this issue, like so many others, is hard and complicated, that that’s a victory unto itself.