I used to judge teachers who quit midyear. How could they abandon their students? Didn’t they sign a contract? Could they just really not cut it? Well, now I get it. Midyear quitting may be unseemly, but it’s understandable. When teachers must abide relentless chaos or fear outright brutality, I get it.

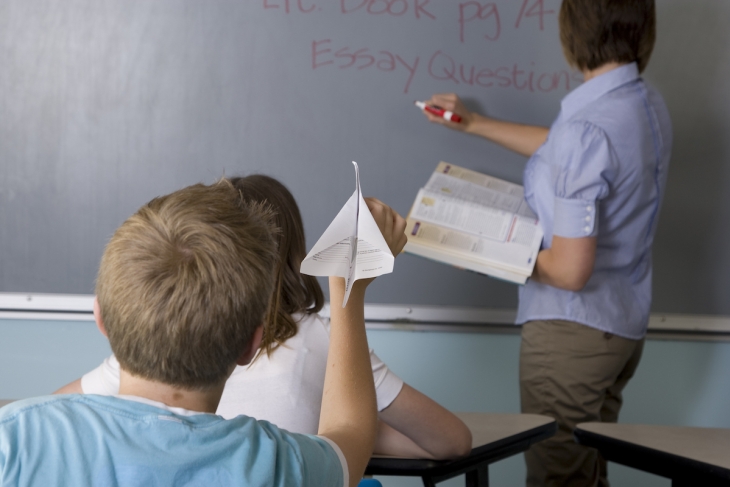

In an online thread, thousands of teachers tell stories about the new normal of students throwing supplies, cussing out teachers, and showing complete apathy toward academic work. PBS ran a more thoroughly journalistic story in which teachers raised the same concerns: “Hitting, biting, spitting, throwing furniture” are common in too many classrooms nowadays.

Whatever metric you use, statistics bear out the anecdotes that emerge both from reporting and from online vent sessions: post-pandemic student behavior remains chaotic. In schools across the country, there was a 9 percent increase in weapon confiscation last year. Violence spiked in districts from North Carolina to Denver. In a 2023 survey of superintendents, concerns about behavior topped academic loses as a major concern: 58 percent cited academics as worse since the pandemic, while 81 percent noted behavior.

And teachers are fed up with this reality on the ground. Two representative surveys capture this dissatisfaction. The first, from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, finds that the greatest concern among teachers right now is behavior. The second, from the Rand Corporation, places behavior as the number two stressor in teacher’s lives, behind only concern for the academic growth of students. Both place teacher pay, the dissatisfaction about which we hear most, far lower.

But surveys miss what this really means in practice.

They don’t capture the stress and adrenaline shock after breaking up a fight. They don’t capture the change in thinking from “these students are disrespectful” to “I don’t deserve their respect”—a shift as subtle as it is emotionally crushing. Nor does it capture teachers’ all-consuming anxiety—fear, even—at the uncertainty of what will happen that day, playing out worst case scenarios like a suspense thriller in their mind.

Teachers are expressing this dissatisfaction. In Akron, Ohio, for example, the union threatened to walk out after a proposed district policy that would redefine “assault” as only incidences that resulted in injury. In Charlottesville, teachers staged an unofficial walkout, calling in sick on a Friday in November and forcing a shut-down the following Monday and Tuesday because of ubiquitous classroom violence. In Portland, a group of principles penned an open letter pleading for help with record-setting incidents of classroom disruptions and physical altercations.

As with any policy issue, the solutions to this behavioral uptick are complex and mostly unsatisfying. How do you improve poverty? Well, it’s economics, tax-policy, healthcare, safety nets, public philosophy and Zeitgeist shifting, philanthropy, institution building, and more.

The causes of today’s spike in misbehavior are multiple: pandemic-era disruptions in schooling and the subsequent unlearning of behavioral norms and habits, learning loss that fosters academic difficulties and so misbehavior, screen addictions, trends in permissive parenting, broader trends of societal disorder, lenient discipline fads in schools, and on and on. As such, the solutions to our behavior crisis involve dozens of levers in public policy and education reform.

With that in mind, below I hazard six behavior-specific recommendations:

1. Keep the federal government out of it.

Even before the pandemic turned the behavior crisis to eleven, the Obama administration arguably set the course for leniency with its 2014 Dear Colleague Letter, threatening legal action against school districts that showed disparities in rates of punishment, thereby forcing schools towards leniency. Policy at such a high level cannot possibly fit facts on the ground. In a district where I worked, a handful of students racked up the lion’s share of disciplinary action. Recent research finds that it’s also just a handful of novice, ineffective teachers who write the majority of office referrals. These outliers skew data and so handcuff administrators from effectively disciplining students. And any federal policy that incentivized strictness would likely cause the debate to swing equally too far in the opposite direction. Most teachers prefer stricter discipline, and so keeping decisions local would likely bring the pendulum swing to a happier middle.

2. Sweat the small stuff.

Too many administrators ignore the minutiae of behavior codes, such as the need for a uniform policy. Why enforce attendance or discipline a child for talking out of turn when there’s a fight in the cafeteria? “We’ve got bigger fish to fry!” But if school staff do not hold the line on small fights, bigger fish come along. Highly successful charter schools adopt a “broken windows” approach to school order—even paying staff whose job it is to replace every burnt out lightbulb, wipe up every scuff on the floor, and reorder any school display. Sweating the small stuff communicates to students that school buildings are not places that tolerate disorder, and that instead they expect excellence from everyone who walks through their doors.

3. Lean on school boards.

School boards can compel buildings to review student conduct codes to tighten up what behavior warrants what response. I’ve written and reviewed a few discipline codes myself. They are the tools that empower or handcuff an administrator’s ability to back up their teachers. If a code of conduct doesn’t allow a detention or suspension for chronic minor disruptions, for example, a building administrator is powerless to help a teacher. What’s more, school boards can include language, such as that recommended in a model policy by the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty that actively requires administrators to impose consequences: “If a teacher removes a student from class due to behavior outlined in this policy, before a return to class, the building principal or other administrative personnel will administer appropriate corrective action.” If the parents-rights movement leaned into school discipline, they might find more electoral success than messaging about explicit books.

4. Conduct a campaign of behavioral transparency.

Historically, attempts to tighten down on student discipline have met with hostile press cycles. When North Carolina required schools to reassess their discipline codes, local media framed it as a vote against “policies to soften racial disparities.” In a report for AEI, Max Eden recommends that districts open up anonymous surveys and conduct annual behavioral audits to see what is really going on. Districts that have done this receive teacher responses such as “we were told referrals would not require suspensions ‘unless there was blood.’” These would provide much needed rhetorical cover for any enterprising education reformer.

5. To teachers, do what you can.

Let me take off my policy wonk hat for a moment and speak to my fellow educators. I’ve worked in chaotic schools. I’ve seen bathrooms with sinks ripped off the walls and other scenes that aren’t fit to describe in pages such as these. I’ve walked down school hallways that reek of marijuana, where the most common sounds are students cursing and teachers shouting. In these scenarios, I had my students working silently, reading, and learning. One year, my students had the highest reading gains at my school. My administration thought I had some special “relationship-building” magic. I didn’t. I simply sat down one day and listed every consequence that I myself could impose where my administration demurred: pulling kids myself from lunch, recess, or gym to impose my own detention, grades for behavior, and whole class consequences, such as extra homework. I tallied over 150 calls home one year (both positive and negative). Like limping with a broken foot, some of these are not “best practices,” but are necessary when administrators cannot or will not maintain order.

6. To unions, take action.

As a conservative, I can’t believe I’m saying this, but local unions may be one of the few places of leverage that we have. At the national level, the major unions have bought into soft-on-consequences discipline, but, as in Charlottesville and Akron, local unions could force change where all other incentives foster inertia. National advocates are too often removed from boots-on-the-ground teachers, but local reps can see what their teachers really need most, and so are more likely to pick up this fight.

—

I’m a stalwart proponent of instructional, reading, and curricular reforms. These are the policies that will win real academic improvements for American children. But no amount of phonics instruction or civics education will mean much if students can’t even hear their teacher. Getting behavior right comes first.