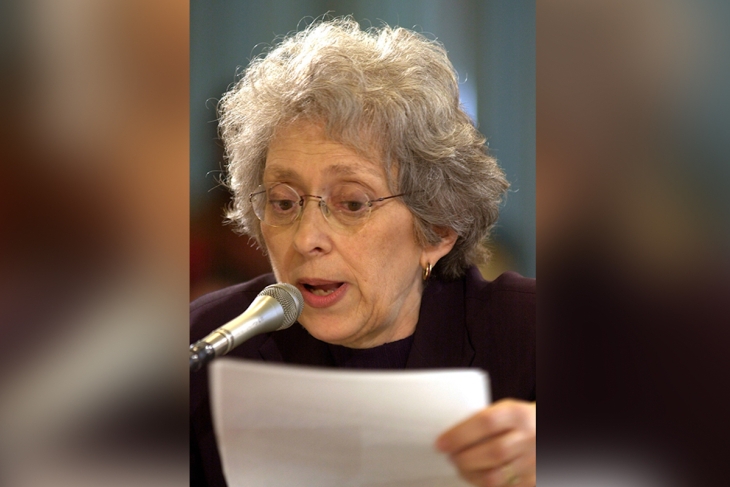

Abby Thernstrom wasn’t a close friend, but she was a lot more than a cordial acquaintance. For as many decades as I can remember, she was both a force to be reckoned with in education and civil rights policy and a treasured colleague in pursuit of excellence and integrity in both realms.

As rigorous a thinker as I’ve ever known, she was a first-rate analyst, data hound, and clear-eyed analyst. Along with her partner/husband/co-author, the distinguished historian Stephan Thernstrom, her most notable works include America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible and No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap in Learning, as well as innumerable articles, op-eds, and more. Yet Abby was far more than a desk-bound scribbler, whether one recalls her decade-plus service on the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education during the formative period of the “Massachusetts miracle” in K–12 schooling, her dozen active years on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, or the thousand panels and events she took part in.

Among the many honors she received (and often shared with Steve) during her lifetime was the Fordham Prize for Excellence in Education (!) and the Bradley Prize. Although a loving mother, passionate grandmother, and dear friend to many, Abby had a tough-minded, suffer-no-fools rigor to her that she applied with equal force to folly wherever encountered. Ultimately known as a neo-con, she was as rigorous toward foolishness on the right as on the left, where I think it’s fair to say she more often found it.

She allowed absolutely “no excuses” for the shortcomings of American K–12 education, for which her prescription was a careful blend of tough love, high expectations, fairness, and color-blindness. But she and Steve made clear that the challenge went beyond schooling and into the culture itself. Today, sadly, we’re more willing to tolerate excuses—and that’s a problem.

Jason Riley got it exactly right: “Abby wasn’t the shy type. She understood that you don’t help people by lying to them about their predicament or urging them to blame their problems on others. She made a career of doing something that ought to be common among public intellectuals but isn’t: gathering facts and reporting her findings without bias and based on the evidence. Neither ideological nor doctrinaire, she acted in the tradition of social scientists like Edward Banfield and James Q. Wilson, who put intellectual honesty ahead of political correctness.”

Even as we celebrate her life and mourn her passing, we can only hope that this mold isn’t permanently shattered.

—

Achieve did something almost no respected nonprofit in my experience has ever pulled off with similar grace and style: It decided, after more than two decades of outstanding work, helmed first by Bob Schwartz and then by Mike Cohen, to close its own doors while ensuring that its considerable intellectual property and many projects and causes will be well looked after.

That doesn’t mean it won’t be missed. I personally and Fordham institutionally have had innumerable connections with Achieve and its leaders over the years. They’ve all been mutually respectful and supportive, cordial, and occasionally playful. About 95 percent of the time we’ve pulled in the same direction, sometimes formally teamed up, as in the American Diploma Project, but more often we collaborated within a looser structure of like-minded organizations, mostly in pursuit of higher K–12 standards attached to college and career readiness.

We didn’t invariably agree. For instance, our reviewers didn’t love the Next Generation Science Standards, which Achieve incubated. Mike Cohen labored long and hard and well for the Clinton administration, while I did the same for Reagan and Mike Petrilli did for Bush 43. But the Achieve-Fordham connections were a classic—now too rare—example of center-left/center-right bipartisanship, combined with easy personal camaraderie. (Another example: Mike Cohen serves on the “practitioner council” of the Hoover Education Success Initiative, with which I’m connected.)

Achieve’s—and Mike Cohen’s—legacy is huge. College Board president David Coleman has nicely summarized it, as well as the challenges that remain:

Achieve believed that education must never be isolated but fully embraced by the business and political worlds. Achieve at its strongest actively engaged CEO’s, governors, and superintendents in the work of education. Mike moved between all of these worlds to build Achieve as an essential force…

So many of us in this field owe a debt to Achieve, Mike Cohen, and the circle of leaders they have cultivated. So many of us became friends at gatherings that crossed state lines in a shared commitment. Let us now be vigilant to strengthen the bonds across sectors and states. Let’s work for ideas and ideals better than partisanship. Let’s especially hold fast to the best of Achieve’s ideas: that students will rise if challenged meaningfully. Let us rise to the challenges of our divided landscape to find insights and actions that may unite us still.

We certainly haven’t seen the last of Mike Cohen, and that’s a very good thing. His wisdom, his wit, his kindness and generosity, his energy and determination that American education must and can be better than it is—we still need that. But what a splendid job he has already done!