Editor’s note: This is the first post in a five-part series about how to effectively scale-up high-dosage tutoring. Read parts two, three, four, and five.

High-dosage tutoring (HDT) is “having a moment”—in the USA, Netherlands, and UK. See here, here, here, here, here (UK), here, and here at Fordham.

Andrew Rotherham, however, weighs in with a cautionary note. He writes:

If you invest in the silver bullet market there is a buy opportunity coming in tutoring. Not just any tutoring, high-dosage tutoring. The word itself sounds exciting—high-dosage!

Here is how these things tend to go. New idea—or not new but reintroduced idea—widely implemented through a funding and think piece gold rush. And widely implemented in uneven ways with little fidelity to the research because of the haste and good intentions coupled with lack of capacity around the field. End result, good idea gets discredited because, on average, it shows little if any impact. You see this around the ed tech sector, class size reduction, teacher evaluations, some reading initiatives, charter schools.

Andy nails it.

This five-blog series is about our shared fear that HDT will scale up badly.

Some quick background: We met on a basketball court thirty years ago. We’ve chased two education reforms in our careers: school culture and high dosage tutoring. We each penned books about school culture, with Mike outselling Bo eight copies to six copies (two more cousins). No traction there.

When it comes to High Dosage Tutoring, however, we’ve been part of some successes, in the USA and in the Netherlands.

Mike’s effort in Boston—Match Education—achieved large gains. Harvard’s Roland Fryer led a replication of HDT in Houston. Alan Safran of Saga Education improved and scaled the program in Chicago and NYC and beyond. Mike Duffy and Jared Tailefer turned the idea into Great Oaks, a HDT-fueled charter school network in cities like Wilmington, Newark, and Bridgeport.

The Amsterdam program, where Bo was an advisor, had students, after half a year, making math gains between 0.43 and 0.70 standard deviations—huge gains. The Bridge Learning Interventions’ version of HDT has been replicated in multiple Dutch cities, and is now scaling up.

We are convinced high dosage tutoring can work. Often does work. HDT has huge potential. But since every other edu-idea that’s been scaled has failed, is there any way to avoid that fate here?

Hell if we know! We’re terrible at politics.

Our contribution is an effort at an explainer on why HDT will not respond well to a “just put money behind it” policy effort.

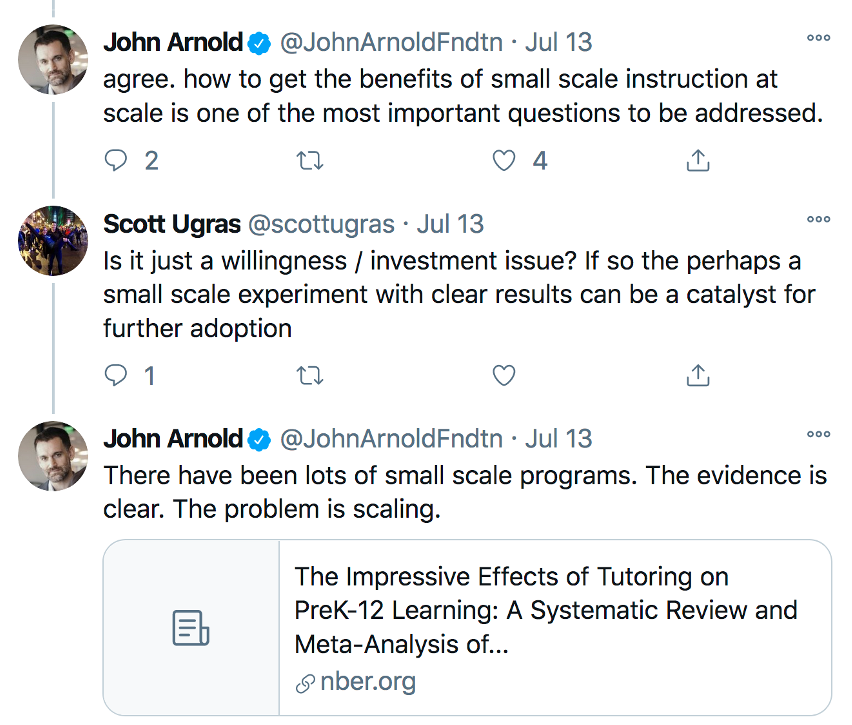

John Arnold puts it this way:

And to explain the tutor scale-up problem, we turn to an apropos analogy: Vaccine development.

This next four blogs in this series are:

- Wednesday: Vaccine-making’s lessons for high-dosage tutoring: It’s weird in there

- Thursday: Vaccine-making’s lessons for high-dosage tutoring: Cells constantly create “new problems”

- Friday: Vaccine-making’s lessons for high-dosage tutoring: A respectful disagreement about research

- Monday: Vaccine-making’s lessons for high-dosage tutoring: How to move forward

“High-dosage tutoring” has become the common parlance. But we mean “high-impact tutoring,” meaning that irrespective of dosage, kids actually made large learning gains when measured in a randomized control trial.

Final note: Mike already co-wrote a cautionary essay for the Brookings Institute on this very topic. But the final product wasn’t cranky enough for his taste. That’s because his co-writer, economist Matt Kraft, a dear friend, is much more optimistic about scaling HDT.

So, Mike turned to Bo, who shares Mike’s (and Andy’s) glass half empty spectacles. Together, we’ll explain why HDT is quite hard to scale, and describe a narrow path to do it right.