Editor’s note: This is the fourth post in a five-part series about how to effectively scale-up high-dosage tutoring. Read parts one, two, three, and five.

Bob Slavin, a wonderful researcher, has written some hard truths about Covid-19 learning loss. He correctly dismisses policy interventions like extending the school year, typical after school programs, and summer school. Those won’t work. Bob believes tutoring, however, will work:

By far the most effective approach for students struggling in reading or mathematics is tutoring (see blogs here, here, and here). Outcomes for one-to-one or one-to-small group tutoring average +0.20 to +0.30 in both reading and mathematics, and there are several particular programs that routinely report outcomes of +0.40 or more. Using teaching assistants with college degrees as tutors can make tutoring very cost-effective, especially in small-group programs.

Effect sizes are a wonky way to describe impact. Our friend Matt Kraft, for example, writes that a 0.20 standard deviation effect in education is large.

Philip Oreopoulos and his colleagues agree with Bob. They recently published a meta-analysis, with very large positive effects—0.37 standard deviations—across scores of tutoring programs, some “high dosage” and some not.

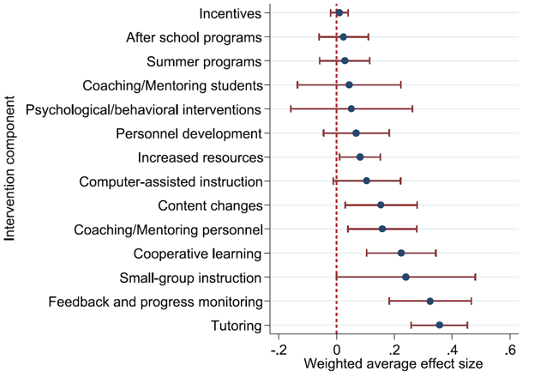

And Dietrichson et al. offer the following chart in favor of tutoring, from 2017:

Clearly, there is reason for scholars to be optimistic about tutoring. And we are pleased that the programs with which we’ve been affiliated are included in that positive research. We’re glad that Experience Corps, Reading Partners, and the i3 study of Reading Recovery had fantastic quality randomized control trials, and that impressive evidence showed gains for students.

So why worry?

We worry because we believe that many more tutoring programs fail than is commonly believed. There are two key drivers of that belief: publication bias and scale-up problems.

Publication bias

This is a broad problem that doesn’t just affect tutoring. Many failed education programs never stick around long enough to get measured. For example, when we scaled high-dosage tutoring from Boston to Houston, it worked. But missing from the story: The Austin Public School system, also in Texas, tried to create its own version of HDT around that time. It quickly failed and disappeared without a trace. That’s not included in “the research.”

When Saga brought HDT from Houston to Chicago, their program succeeded. But at the same time, another Chicago school network launched its own HDT program. That one died after nine months. That’s also not included in “the research.”

When Mike did HDT in our Boston charter school, we deployed literally those same tutors into nearby district schools. The charter students received large gains; the district students had no gains. Indeed, every time we’ve been part of a successful tutoring program, one which “enters the tutoring scholarly literature,” we’ve seen a similar program fail, yet disappear too fast to ever be captured.

Imagine a group of people who try an experimental drug, have bad outcomes, but nobody notices the bad ones, and only notice the good ones, so the drug overall seems successful. (You don’t have to imagine too hard: hydroxycholoroquine for Covid-19).

There are presumably hundreds of such tutoring failures. We believe the positive research story omits these.

Scale up problems

With vaccines, the 1 millionth dose is identical to the 2 millionth dose. But that can’t happen with education programs delivered by human beings.

In particular, education programs that work small often don’t work when they get big. A famous example: Fifty-eight kids who benefitted from the oft-cited Perry Preschool Project in 1962 didn’t translate so well to 18,000 children in Tennessee or to a similar program in Quebec. For a more recent example: Last month our friend Ben Feit published a study finding that Texas charter schools did not scale up well.

Tutoring—not high dosage tutoring, but what we might call “regular tutoring”—already failed in a big national scale up: the George Bush/Ted Kennedy No Child Left Behind version. Again, it’s hard to get the details right.

Every education intervention, including tutoring, requires a newly formulated, carefully calibrated program. It’s details ought to depend on which students it serves, whether it’s optional or mandatory, which tutors it uses, what time of day its offered, whether it’s online or in person, what the tutor-student ratio is, what curriculum is used, what the leadership is like, the overall school culture, and more. There is no de-situated, de-contextualized “thing at rest,” no vaccine. Many have written about the need to consider if a program is “hard to scale”; Matt Kraft’s version is described here by Matt DiCarlo.

The evidence on tutoring is, we believe, choppier than we would have wished.

So what to do?

Tune in Monday.