Most agree that America must increase the racial and socioeconomic diversity of its selective high schools and colleges, as well as participation in its top professions. Yet debate rages over how best to achieve that praiseworthy goal. In K–12 education, the impulse has often been to relax standards or even give up on notions of academic excellence or giftedness in the name of equity and inclusion. While this approach appeals to some, it risks lowering the ceiling, holding back many young people who are ready to zoom ahead, and in the long run, diminishing the country’s competitiveness.

A surer approach is to increase the supply of top-notch education offerings in order to help more high-potential kids from disadvantaged backgrounds compete successfully with others of the nation’s best and brightest. That’s a tall order and one that U.S. education has long struggled to achieve. Studies by Johns Hopkins professor Jonathan Plucker and others have documented stark “excellence gaps” between high- and low-income pupils. A groundbreaking analysis of patent data by Harvard’s Raj Chetty and colleagues revealed that high-achieving children from low-income backgrounds rarely become inventors—what they call America’s “lost Einsteins.”

We at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute have also sounded the alarm about a meritocratic ladder with missing rungs and too narrow a top, as well as the inadequate attention given by U.S. schools to academically talented children. In 2011, we released a study that examined a national sample of third-grade high-achievers and found that a sizable number “lost altitude” by eighth grade. More recently, we published an analysis showing that Black and Hispanic students participate in gifted programs at lower rates than their peers (a phenomenon we termed the “gifted gap”). Our team also published a book showing that, while Black and Hispanic students have been participating in larger numbers in Advanced Placement classes, their passing rates on AP exams show the effects of weak preparation in elementary and middle schools.

Despite widespread exposure of these problems and valiant efforts by advocates, our nation’s most-able students continue to be overlooked—and if they come from poorer homes and neighborhoods the overlooking is almost certain to be worse. According to the National Association for Gifted Children, twenty states don’t even bother to report the number of students identified as gifted, twenty-three states fail to provide any funding for gifted education, and thirty-two states do not require universal screening for giftedness. At the federal level, the sole program dedicated to supporting gifted students is the tiny Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Program.

Our home state of Ohio has gotten a couple of key policies right. For one, it has long required school districts to identify students as gifted and talented using a broad definition and a variety of metrics. More recently, the Buckeye State adopted a universal screening policy for giftedness. Ohio incorporates measures of achievement and growth among gifted students in its school accountability system, and it provides modest funding for identification and services. All good, as far as they go. But are they enough?

We decided to dig deep into the outcomes of high-achieving students in Ohio. How are smart kids there doing? Are they staying on top from elementary through high school? Are most of them acing their college exams and heading to four-year universities? Do we see disparities by race and socioeconomic status, even among students who had done well on their third-grade exams? And what about being formally identified as gifted—does that provide an extra boost?

To examine these questions, we turned to Scott Imberman of Michigan State University, a first-rate economist whose work includes a widely-cited study on the effects of gifted programs. We’re pleased to present his comprehensive study, Ohio’s Lost Einsteins: The inequitable outcomes of early high achievers, which relies on Ohio’s longitudinal databases containing anonymous student-level records. The focus of his analysis is the academic trajectory of the state’s “early high achievers,” defined as students who scored in the top 20 percent on third-grade exams in math or English language arts (ELA).

The first part of the report documents the basic outcomes of these early high achievers. Regrettably—but consistent with previous national studies—we see “excellence gaps” emerge by economically disadvantaged status and for Black students.

- On state exams in grades 4–8, economically disadvantaged early high achievers lost ground to their nondisadvantaged, high-achieving peers, indicating that excellence gaps tend to widen over time. In similar vein, Black early high achievers made less progress over time on state tests than their peers from other races.

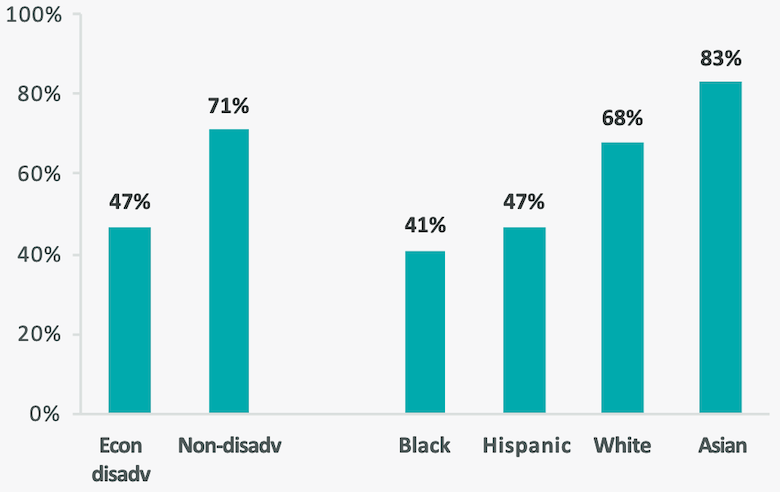

- Less than half of economically disadvantaged and Black early high achievers took the ACT—47 and 41 percent, respectively—which is the predominant college entrance exam used in Ohio. This compares with 71 percent of non-disadvantaged high achievers. (During the period of this study, ACT or SAT participation was voluntary in Ohio.)

- The average ACT math and reading scores of economically disadvantaged and Black early high achievers fell short of their more advantaged peers. For instance, the average ACT math score for economically disadvantaged high achievers was 23, while the average score for non-disadvantaged high achievers was 25.

- Just 35 percent of economically disadvantaged and 26 percent of Black early high achievers went on to enroll in four-year colleges. This compares with 58 percent of non-economically disadvantaged high achievers who enrolled in such institutions.

Figure A: ACT test participation (top) and 4-year college enrollment (bottom) among early high achievers

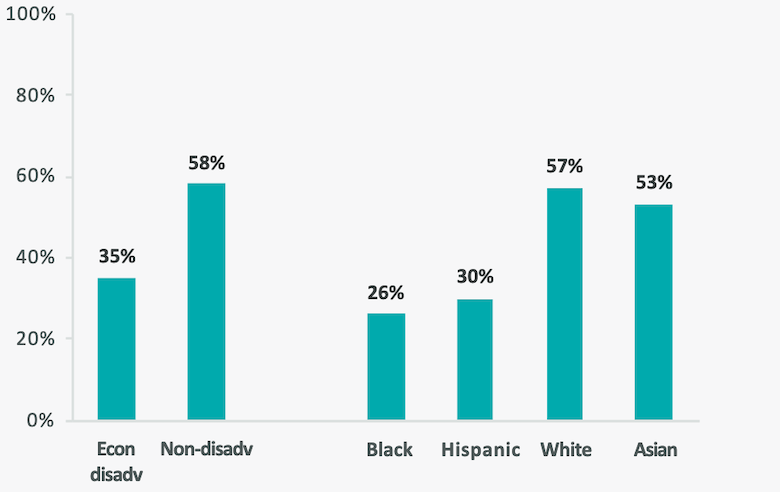

The report then turns to questions of gifted identification. Here we see that fewer than half of Ohio’s early high achievers are formally identified as gifted by eighth grade, reflecting either a high bar for identification or perhaps uneven application of the criteria for identification.[1] Thus, the terms “early high achiever” and “gifted student” are not interchangeable—and the raw outcomes data show that those high achievers who are identified as “gifted” outperform their non-identified peers.

Economically disadvantaged and Black students were less likely to be identified. By eighth grade, 34 percent of economically disadvantaged high achievers were identified as gifted, compared to 53 percent of their nondisadvantaged peers. Meanwhile, 30 percent of Black early high achievers were identified as gifted versus 52 percent of White and 71 percent of Asian high achievers. Note that, during the period of this analysis, Ohio did not have a universal screening policy—that changed in 2017—possibly explaining some of the disparity in identification rates.

Figure B: Gifted identification by grade 8 among early high achievers

Rigorous causal analyses indicate that gifted identification itself provides a small boost to early high achievers from all backgrounds on state math and ELA exams, but the gains are more substantial for Black students, particularly in math. Though not causal evidence, Black high achievers who are identified as gifted outperform non-identified Black high achievers on ACT and AP performance and college-going outcomes.

Due to data limitations, this study cannot answer questions about whether receiving gifted services drove the results—Ohio does not mandate such services, just identification—or even which specific types of service benefitted children most. The state does not produce systemic data about the sorts of gifted services that students receive—if indeed they receive them—so we don’t know whether gifted students are mostly receiving meager hour-a-week “enrichment” or more intensive programming with specialized curricula and classrooms. What happens after a student is identified remains hidden inside a black box.

Nevertheless, it’s clear from the research—this study included—that more needs to be done on behalf of America’s high achieving kids, especially those from low-income backgrounds. What to do? Start by placing the needs of high-ability kids on the policy agenda. Consider just a few starter ideas:

- Screen all children at least once in elementary school for academic giftedness, ideally using the state assessment rather than a separate exam.

- Ensure that high-achieving (but not formally gifted) pupils have access to gifted programs and work to build sufficient capacity to make that possible.

- Include data about gifted students’ achievement and growth on annual school report cards.

- Require schools to provide gifted services and report pupil outcomes by the type of service received.

- Identify all students in the state who show potential for success in selective colleges by requiring high schoolers to take the ACT or SAT at least once.

- Remove barriers to AP or IB exams by fully covering test fees for low- and middle-income students.

- Ensure that all students are well-versed in higher education opportunities, including information about financial aid and which colleges might be an appropriate match.

- Empower parents of high-achieving children with options if their local school doesn’t offer satisfactory gifted programs or advanced coursework.

- Create specialized schools that cater specifically to the needs of gifted students and high achievers.

—

Thousands of early high-achieving children—including smart kids of poor and working-class parents from places like Cincinnati, Dayton, and Mansfield, Ohio—are drifting their way through middle and high school. They don’t end up taking AP exams, achieving high marks on their ACTs, or going to four-year colleges, as one might expect. This not only limits these kids’ opportunities to move up the social ladder, but also threatens the nation’s economic competitiveness and derails our aspirations for a more just society where children from all backgrounds can become inventors, doctors, and business leaders. Rather than buying into the false assumption that high-achieving kids will do fine on their own, we need to do a better job of making sure that all high achievers, including those from low-income backgrounds, get the education they deserve.

[1] To be identified as gifted in math, students must score at the ninety-fifth percentile or higher on an approved nationally normed test; the same bar applies for identification in reading, science, and social studies. Slightly different criteria apply for identification in superior cognitive ability, visual or performing arts, and creative thinking, the remaining categories of giftedness in Ohio. For more on Ohio’s gifted identification policies and practices, see Ohio Department of Education, Assessments Approved for Gifted Identification and Prescreening (2021).