One piece of news that you might have missed in the hot summer months came from the National Assessment Governing Board (NAGB), which oversees the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a.k.a. The Nation’s Report Card.

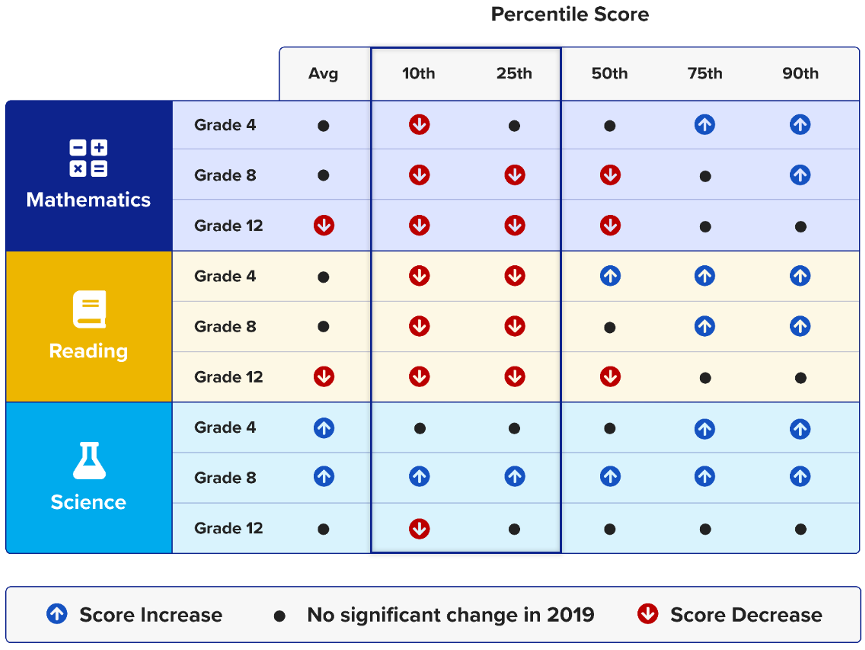

The good folks at NAGB had the smart idea to look at student achievement trends over the decade from 2009 until 2019. (They also have new “before and after the pandemic” data soon to emerge.) What they found was eye-opening. Whereas America’s higher achieving students—defined here as those in the top 10 or 25 percent of the distribution on the NAEP scale—held steady or even gained ground, our lowest performing kids—those in the bottom 10 or 25 percent—saw their test scores fall in both reading and math, at least in the fourth and eighth grades.

Figure 1: Changes in average and selected percentile scores, by assessment: 2009–2019

Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2009–19 Mathematics, Reading, and Science

What didn’t come through clearly in some of the ensuing commentary was that this news wasn’t all bad. As my colleague Brandon Wright argues elsewhere, we should celebrate the fact that high achievers are doing better over time. It’s good for them, it’s good for the country, and it’s a plus for our elementary and middle schools. Yet somehow, in today’s environment, it’s mostly seen a bad thing because it widens gaps and thereby leads to greater inequality.

We should reject that viewpoint, even as we redouble our efforts to boost the low achievers, too. The more any kid learns, the better. Education is not a zero-sum game where there must be both winners and losers. And we all benefit if our high-achieving kids learn more and go on to cure cancer or fix climate change or out-compete China.

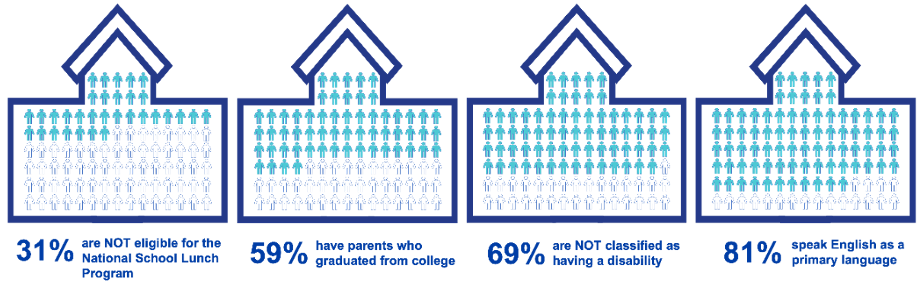

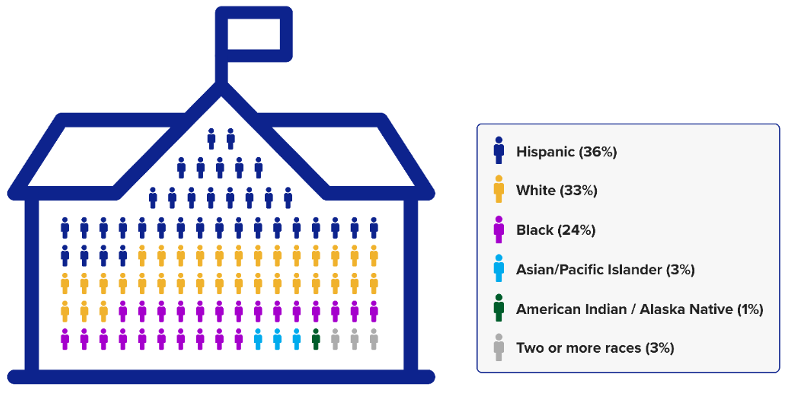

It’s also important to note that the gaps are widening on achievement, not race or income. Indeed, the low-achieving group includes a surprisingly large number of white and middle-class students, including those whose parents are college-educated. And while the high achievers are disproportionately drawn from white, Asian, affluent, and college-educated families, not everyone is.

Figure 2: Selected characteristics of lower-performing students

Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2019 Reading, Grade 8

Figure 3: Racial/ethnic composition of students who performed below the 25th percentile

Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2019 Reading, Grade 8

So now let’s get to the big question: What might be causing these diverging trends? The Governing Board is silent on this question, as it is supposed to be. It’s a just-the-facts-ma’am kind of outfit, and everyone is supposed to understand that NAEP, for all its virtues, cannot explain causation. But the rest of us can speculate, even as we are careful not to engage in mis-NAEP-ery.

Let’s walk through a few hypotheses, while remembering that what’s causing the decline in scores for low achievers may not be the same factors that are causing the increase in scores for the high achievers.

First, we should consider possibilities that have nothing to do with school. After all, any test score encompasses everything a child has experienced in his or her life to that point, including socioeconomic conditions at home during their early years; the richness of the language they have heard from their parents and other caregivers; preschool experiences; and yes, instruction in the K–12 system. Since children spend much more of their time outside of school than inside, we should always expect that something outside of school could be causing changes in test scores for the population as a whole. That might include:

- The impact of the Great Recession on children’s socioeconomic circumstances.

- Ongoing changes that have driven inequality in society writ large, such as “assortative mating” and the intensive—sometime hyper—parenting of college-educated adults.

- Shifts in how children are spending their time, especially with respect to screen time.

Other possible explanations are more directly related to schooling:

- Funding cuts in the wake of the Great Recession.

- The move away from the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) act’s strict test-based accountability system for schools in favor of the looser requirements of the NCLB-waiver era, and eventually the laissez faire approach of the Every Student Succeeds Act.

- The shift to the higher standards, and loftier instructional goals, of the Common Core.

Let’s explore whether any of these possibilities make sense.

The high achievers fly higher

Let’s start with the high achievers. What might be helping our top fourth and eighth graders do better than ever?

It’s hard to believe that anything in the broader economy can explain the trend, given the terrible aftereffects of the Great Recession.

It’s also difficult to fathom that the increasing prevalence of smart phones and other screens in the lives of children would be beneficial, though maybe it’s not impossible. Perhaps our most motivated students have been using their screens to learn more and indulge their curiosities? Maybe they are tuning into daily Khan Academy lessons and YouTube videos of educational content? I’m doubtful, but perhaps?

Or maybe we are mostly seeing the benefits of America’s affluent, college-educated parents marrying one another, waiting until they are older and richer to start their families, and then plowing an enormous amount of time and resources into raising their children. Maybe all that money spent on organic food and afterschool tutoring and summer enrichment activities is paying off. Maybe.

In my view, though, a more plausible explanation is that schools are simply paying more attention to their higher-achieving students than they were in the early 2000s. As we at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute reported back then, it was a problem that NCLB was so focused on helping the lowest performing students reach a low level of proficiency. Teachers admitted that they prioritized their struggling students over everybody else, certainly including their high flyers. Everything in our accountability system encouraged them to do so.

As NCLB waivers and eventually ESSA allowed states to move to a focus on student growth, perhaps that started to change. At the same time, the shift to the Common Core encouraged teachers to raise their level of instruction, and to adopt more challenging curricular materials. All of this might have benefited our high-achieving students, as they got more attention from their teachers, and received instruction that was more closely targeted to their level of readiness.

Granted, this hypothesis requires a multi-step process to be true, happening at huge scale in an enormous, continent-wide country.

Whatever the explanation, I’m happy about it and would love to see some scholars with serious methodological chops find clever ways to test one or more of these hypotheses. It would be great if we could keep these trends going, even in the wake of the pandemic.

How low can we go?

Next to the bad news about our low achieving students. Frankly, I think this puzzle is easier to solve.

I’ve argued before that the Great Recession had a negative impact on the achievement of our poor and working-class students. That’s not the same group we are talking about here, but there is obviously a lot of overlap. That impact came directly in the form of the difficult years for families when these students were infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Income plummeted. Poverty rates rose. Food insecurity grew. All of this would make a difference with these tykes’ later achievement. Consider, for example, findings from NWEA that showed declining test scores at kindergarten entry in the early 2010s. I suspect this also explains why so many of our social indicators were heading in the wrong direction even before the pandemic—such as the murder rate, auto accidents, and more. The downstream effects of early-childhood hardship can take years or even decades to become clear.

The impact of the Great Recession also happened indirectly, in the form of the dramatic K–12 spending cuts that happened from 2011 to 2014. Kirabo Jackson showed convincingly that these cuts had a negative impact on achievement. And it’s not hard to imagine that those spending reductions might have hurt the lowest-performing kids the most, as easy targets for cuts would have been tutoring programs, literacy coaches, and other extras that schools may have been directing towards their struggling students.

The screen-time story also makes more sense here, as we know that kids are spending dramatically more time on devices and on social media, and that could be getting in the way of learning. Especially if low-achieving students spent more time on screens than their higher-achieving peers.

And then there is the end of No Child Left Behind and the rise of the Common Core, which could be the flipside of the story with the high-achieving students. Moving away from the proficiency-only policy of the NCLB era, and toward a focus on growth and rigorous standards, encouraged a shift away from the drill-and-kill of basic skills, toward a higher level of instruction. While I believe that was the right thing to do and probably helped the majority of students, it is possible that teachers’ lessons started going way over the heads of our lowest-performing students, leaving them behind. Indeed, we have heard concerns all along from teachers that they are struggling to use the newer, higher quality instructional materials with their lowest-performing students. They have asked for more help to “scaffold” instruction, and it’s only very recently that many of the publishers have been able to offer decent advice on that front.

—

To repeat, these are educated guesses, and we would be better off if analysts could begin to see which of these theories might have a basis in the evidence.

In the meantime, we are about to find out from the Long Term Trend release whether we are coming out of the pandemic in even worse shape than we were going in. Understanding what happened in the pre-pandemic era might help us do better by kids in the post pandemic era and beyond.