In many communities, public school systems compete with an increasingly complex and frequently overlapping set of alternatives for students and families, including charter schools, public schools in other districts, voucher programs, tax-credit scholarships, and education savings accounts, as well as traditional private schools, microschools, and homeschooling.

We at Fordham view this as a healthy development, both because we believe in the fundamental right of parents to choose schools that work best for their children, and because of the large and ever-growing research literature demonstrating that competition improves achievement in traditional public schools. That “competitive effects” are largely positive should be seen as good news for everyone, as all of us should root for every sector of American education to improve. And it means that the whole “school choice versus improving traditional public schools” debate presents a false dichotomy; we can do both at the same time. Indeed, embracing school choice is a valuable strategy for improving traditional public schools.

Yet despite the amount of attention that school choice receives in the media and among policy wonks, politicians, and adult interest groups, the extent of actual competition in major school districts is not well understood. We were curious: Which education markets in America are the most competitive? And which markets have education reformers and choice-encouragers neglected or failed to penetrate?

Those questions prompted our newest analysis, The Education Competition Index: Quantifying competitive pressure in America’s 125 largest school districts, conducted by David Griffith and Jeanette Luna, Fordham’s associate director of research and research associate, respectively. The study seeks to quantify the extent to which competition is occurring by estimating the number of students enrolled in charter, private, and homeschools in each of the nation’s 125 largest school districts in spring 2020 and then dividing that sum by an estimate of a given district’s total student population (which includes students in traditional public schools). The resulting quotient—the report’s measure of the competition facing a district—is the combined market share of all non-district alternatives. While this is not a perfect measure (we can’t account for inter-district open enrollment, for instance), it is as good an estimate as current data allow.

In addition to calculating the competition that districts face for all students, David and Jeanette also crunch the numbers for individual subgroups, including Black, White, Hispanic, and Asian students, to determine the percentages of school-age children in those subgroups who are attending non-district alternatives.

As the report explains, even calculating these seemingly simple figures required a bewildering number of decisions. For example, because of the variation in state and local kindergarten policies and the data conundrum relative to high school dropouts, the report relies on enrollment in grades 1–8.

In the end, the study’s findings reveal several interesting patterns. First, most of America’s largest districts face only modest competition for students (though there is considerable variation). In the median district, approximately 80 percent of students enroll in a district-run school, and approximately 95 percent of students do so in the country’s “Least Competitive Large District,” namely Clayton County, Georgia. Meanwhile, the country’s “Most Competitive Large District”—Orleans Parish, Louisiana, where there are no district-run schools due to reforms implemented in the wake of Hurricane Katrina[i]—is a clear outlier. In the country’s second and third most competitive districts, the San Antonio Independent School District (TX) and the District of Columbia Public Schools (DC), half of students enroll in non-district schools.

In addition to facing low levels of competition in general, most large districts face more competition to educate White students than they do to educate their non-white peers. After all, White students are much more likely to attend private schools. Yet between 2010 and 2020, the ground shifted: More districts are now competing to educate non-white students, thanks largely to the growth of charter schools. Specifically, 116 of 125 large districts saw an increase in non-white students’ access to options other than traditional district schools in the last decade (with the median large district seeing a 7 percentage point increase). The coauthors commend this trend even as they conclude that we need more, as well as more affordable, non-district alternatives, especially for traditionally disadvantaged groups.

The full report includes several interactive figures that allow readers to see how specific forms of competition have evolved in specific districts and racial subgroups. So, by all means, jump in and click around to your heart’s content.

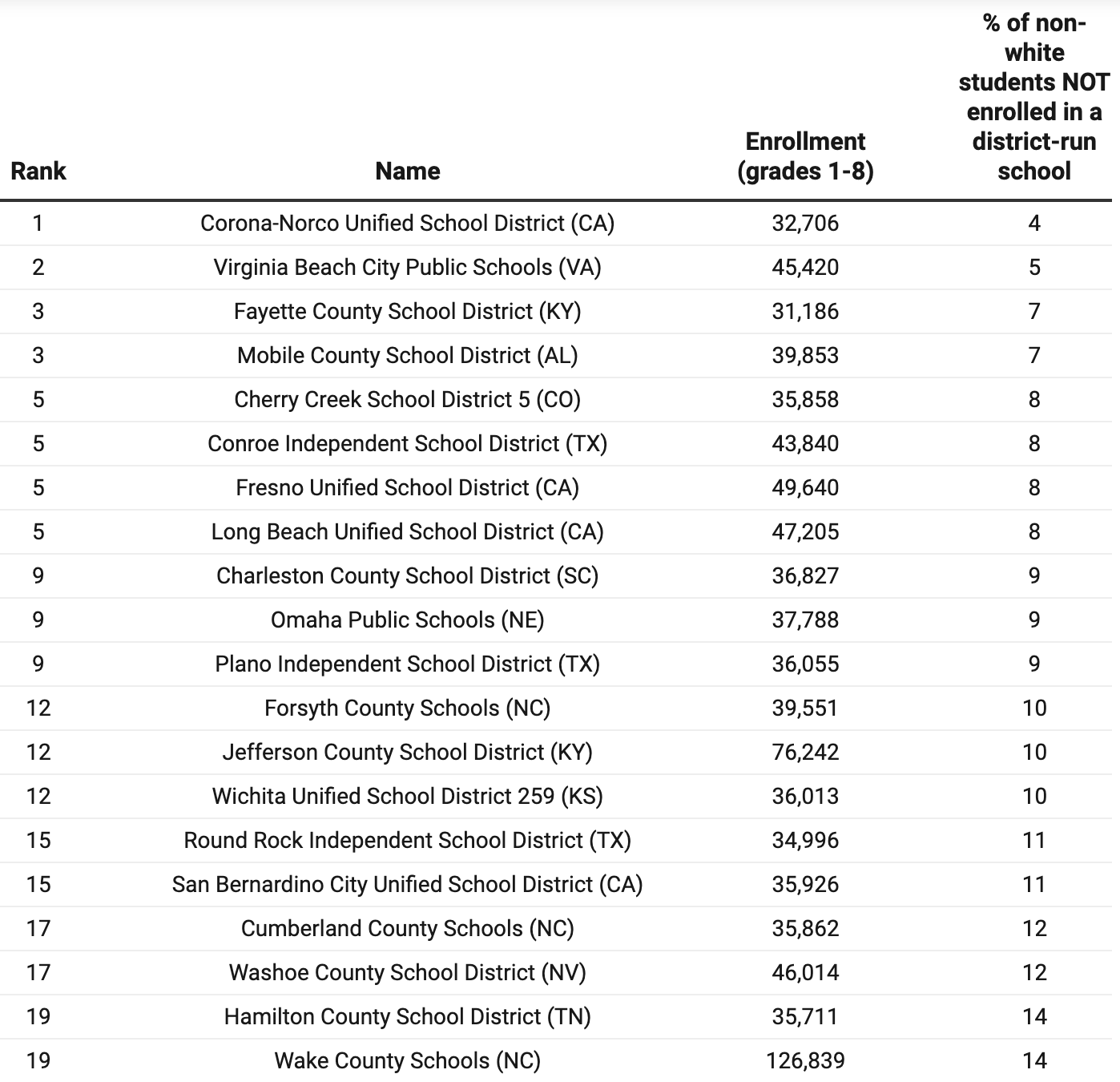

But before you do—especially if you’re an education reformer keen to expand school choice for kids who need it—take a look at the following table, which shows the top 20 major urban districts where relatively few students of color attended non-district alternatives as of 2020. (The full version in the report ranks districts one through seventy.) In our view, these districts are ideal targets for charter school expansion.

Table 1: Major urban districts that face the least competition to educate non-white students, top 20

Notes: Urban districts are those where private, charter, and traditional public schools with urban locale codes account for more than half of total public and private enrollment.

Table 1 shows that, of the twenty major urban districts with the least competition, two of them (Cherry Creek School District 5 and Mobile County) are located in Colorado and Alabama, which have the second and third best “state public charter school laws” (respectively) in the nation, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Fayette and Jefferson County school districts in Kentucky and several urban districts in Texas—including those in Plano, El Paso, and Round Rock—are also in dire need of more options for students of color. The same can be said for Black and Brown kids in multiple urban districts in charter-friendly North Carolina, including in the counties of Forsyth, Cumberland, and Wake. Making more progress in Nevada could also have a big payoff, given the underperformance of Washoe County (i.e., Reno), where just 12 percent of students of color attend an option other than their district-run school.

So, a big heads-up to school choice advocates in search of fertile terrain. Take a good look at these districts because they need you. They need your energy, your resources, and your commitment to expand charter schools and other options.

Because, at the end of the day, just 7 percent of all public school students attend a public charter school. It’s a proverbial yet precious drop in the bucket. Look, we already know that the growth of high-quality charter schools benefits low-income, Black, and Hispanic students academically. So, it follows that we need more of them.

Who’s listening?

[i] As of 2020, seventy-eight of the city’s eighty-six schools were overseen by the Orleans Parish School Board and New Orleans-Public Schools (NOLA-PS). According to the Cowen Institute, all but three of these schools are independent public charter schools; NOLA-PS does not directly run any of the schools under its purview. See https://cowendata.org/reports/the-state-of-public-education-in--new-orleans-2019/governance.