The August release of the latest Education Next poll set the education-reform field ablaze, for it showed a sizable and worrying decline in support for charter schools. We wonks weighed in with our best guesses about what might explain this unexpected trend. Among the factors raised: the overall political environment as we passed from the Obama Era to the Age of Trump, which might chill support for charters on the left; charter scandals and lackluster performance, at least in some states; and the movement’s own obsession with ultra-progressive causes, which might impede support on the right. If only we could improve charter quality, some advocates claimed, we’d see our poll numbers turn around. Or perhaps, others wondered, we need to widen the base of charter support by expanding charters into the affluent suburbs.

Plausible speculations all, but speculations nonetheless.

Now, however, we have a bit more data to inform our analyses. A major education policy organization—a credible source that has asked to remain confidential—gave me access to survey results from a 1,000 person national poll with 300-person “supplements” in a dozen states. The data come from summer 2017, and it happens that the pollsters included a question about charters—not a great question but one that allows us to test out some of the hypotheses about waning charter support.

The question put to a representative sample of registered voters was: “Please indicate whether you support or oppose creating more charter schools—public schools run by private companies or nonprofit organizations—to compete with traditional public schools.” You don’t have to be a charter school apologist or polling expert to see that this question is worded in a very charter-unfriendly way. “Private companies” feeds into the narrative that charters are about “privatization”—a concept that many voters hate—and very few charters are actually run by such firms. Many voters also don’t like the notion of public schools “competing” with one another.

But it doesn’t seem to matter because the survey found that 40 percent of Americans support charters, virtually identical to the 39 percent identified by Education Next with a question worded much more fairly. Still, keep the language in mind.

Now let’s look at how charters fared in the state-by-state polls (nine of the twelve states have sizable charter sectors). Here are the results, in order of charter support. Keep in mind the small sample size, which makes minor differences less reliable.

Figure 1: Support for charter schools in nine states

Now we have another Rorschach test for reformers. What to make of this? Thanks to data dug up by our crack research intern Nicholas Munyan-Penney, I was able to investigate lots of possible explanations. Of course, with only nine data points, all of this must be taken with a measure of skepticism. But let’s look for some patterns nonetheless.

At first glance, it looks like simple ideology could be at play. The top two states for charter support are red; the notion of competition probably plays well there. And deep-blue Illinois lands near the bottom.

But it’s not so simple. There’s California, bluest of them all, in third place. And what is Louisiana doing so far down?

Could voters be responding to school quality? (Please let that be the answer, I hear all of you good-government types screaming!) No doubt Ohio has been (in)famous for its lackluster quality and its numerous scandals, so the last-place spot is well deserved. (Let me point out that we at Fordham, along with many partners, are making some real progress at fixing that.) But according to CREDO’s analysis of year-to-year math gains, New York’s charters are the best, followed closely by Tennessee, Louisiana, and, further back, Illinois. Charters in California, Colorado, and Georgia all do about the same as traditional public schools, while Arizona and Ohio charters do worse. Put all of this together and it’s a big jumble.

Figure 2: Support for charters schools versus their impact on math achievement

Could it be the size of the charter market? Are charters more popular when there are more of them, or when their students make up a greater percentage of the school population? No, that would put Arizona, Colorado, and Louisiana at the top of the list, and Tennessee at the bottom. Maybe charter schools are more popular in growing states, where they can serve as a “release valve” for growing public school populations. That could explain Georgia and Tennessee, but what about Colorado? I also don’t see a relationship between charter school growth and their popularity, or lack thereof.

So what is it?

Here’s one last thought, inspired by the writing of Matt Ladner and Derrell Bradford: Perhaps charter schools are more popular when they serve more affluent students, not just low-income kids. Let’s take a look.

Table 1: State charter school support based on the percentage-point difference in the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch in charter and traditional public schools

|

State |

Support for Charters |

Difference in FRPL Rate (Charters - TPS) |

|

Georgia |

50% |

+6% |

|

Tennessee |

45% |

-26% |

|

California |

42% |

+3% |

|

Arizona |

40% |

+12% |

|

Colorado |

39% |

-15% |

|

New York |

38% |

-28% |

|

Louisiana |

37% |

-8% |

|

Illinois |

33% |

-38% |

|

Ohio |

24% |

-30% |

What this shows is that, for example, Georgia’s traditional public schools serve a higher proportion of low-income students than Georgia’s charter schools do—a difference of 6 percentage points. In Ohio, meanwhile, traditional public schools on average have 30 percentage points fewer students eligible for free or reduced price lunch than do charter school peers.

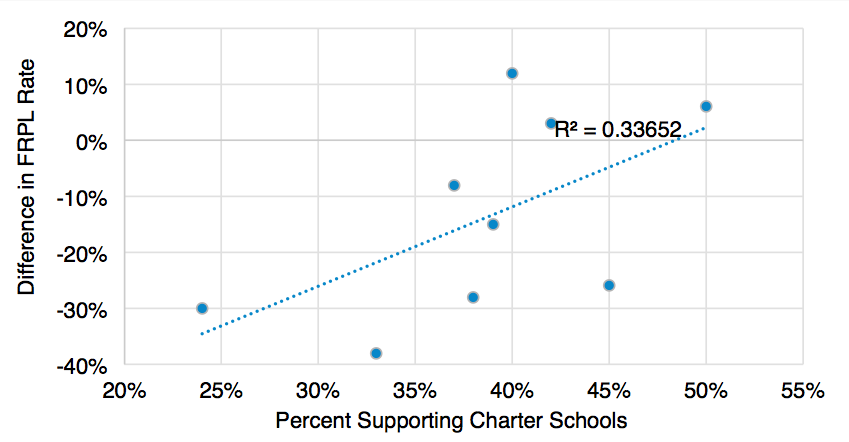

And, sure enough, there appears to be a relationship, with a few outliers. Let’s see that visually.

Figure 3: State charter school support versus the percentage-point difference in the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch in charter and traditional public schools

Boom! To be clear, I’m not going to present this to a peer-reviewed journal; this is hardly rock-solid evidence. But it sure suggests to me that, if we’re looking for a generalizable explanation for state-by-state differences in support for charters, the degree to which they serve middle class kids and not just low-income children might be a leading candidate.

Yes, there are exceptions. Support for charter schools in Tennessee should be much lower according to this theory; perhaps they are helped by the state’s conservative leanings and the schools’ strong track record on quality. I also can’t explain why charters aren’t more popular in Arizona or Louisiana. But this certainly shows the strong headwinds faced by the sectors in New York, Ohio, and Illinois.

For many states, then, charter demography may well be destiny, at least when it comes to public support, at least in this moment in time.

If that’s true, what does it mean? First, it would put charter schools in line with the old liberal adage that “a program for the poor is a poor program.” It’s hard to maintain public support for a targeted investment, especially when the beneficiaries are themselves poor and relatively powerless. This is why Social Security is much more popular than most welfare programs.

Second, it might tell us about how the public views schools. Voters might perceive “schools for poor kids” as low-quality schools. That is of course unfair and prejudiced, but it may reflect the reality of public opinion. And not just in education. We perceive neighborhoods that affluent people can afford as “nice neighborhoods”; restaurants that affluent people can afford as “nice restaurants”; and public schools that affluent people can afford as “nice schools.”

Third, and less cynically, perhaps when charter schools serve a broader population, including middle class kids in the suburbs, more people come into contact with them. And familiarity breeds positivity.

Regardless, these data provide yet more reason for the charter movement to get busy building schools in neighborhoods far and wide, and working to serve affluent kids, low-income kids, and everyone in between. Charter schools for poor children have done wonders. But if we want to maintain support for them, they ought not be the only type around.