Earlier this month, John Winters, associate professor from Iowa State University, released a study, What You Make Depends on Where You Live: College Earnings Across States and Metropolitan Areas, which examined the economic premium of earning different college credentials across all fifty states. Some of what he found reinforces previous narratives, as earning more advanced degrees often leads to increased earnings for workers. However, the study also highlighted some nuances in how much college educated workers make, including:

- The earnings premium of a bachelor’s degree, in comparison to a typical high school graduate with no college, varies widely across states, ranging from around 20 percent to more than 100 percent.

- Obtaining a credential often pays the largest economic dividends in larger urban areas.

- There are disparities in the college earnings premium by race and ethnicity, with white and Asian workers benefiting the most.

So, essentially, the question of whether college is worth it now becomes a bit more complicated. Instead of an overwhelming, “yes,” the answer becomes “usually, in some places, for some people.”

While Professor Winters highlights these macro trends across states, policymakers and students may also be interested in the economic premium that specific institutions of higher education provide to their former students.

From a lawmaker perspective, it’s critical that the $130 billion annual investment in higher education is efficiently targeted toward institutions that are shown to equip students to enter the twenty-first century workforce and provide a strong return on investment for the taxpayers who subsidize their educational endeavors.

And for students, when choosing to pursue a postsecondary credential, it’s important that they know the value of credentials and whether they’re worth the amount they’d pay to obtain them. Just as stock analysts are able to assess the value of individual stocks, students and lawmakers should be able to evaluate the time it takes to recoup the cost of earning a credential at each institution across the United States. Knowing the economic premium that students obtain, in comparison to how much a high school graduate makes with no college experience in their state, can help them do just that.

This is part of why, earlier this spring, Third Way, where I’m a senior fellow, introduced a different way of assessing the value of individual institutions, known as a the “Price-to-Earnings Premium,” or PEP. Any additional earnings that postsecondary students obtain beyond the typical high school graduate within their state can be used to pay down the net cost of earning that credential in the first place. Therefore, our PEP provides students and lawmakers with an estimate of how long it takes the typical student to recoup their educational investment. Here’s its formula:

Number of Years to Recoup Net Cost = Total Average Net Price / (Post-Enrollment Earnings - Typical High School Graduate Salary in that State)

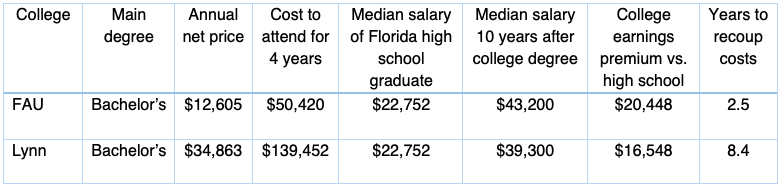

To demonstrate how this works in practice, consider two institutions located just 1.3 miles from each other in Boca Raton, Florida: Florida Atlantic University (FAU) and Lynn University.

Both institutions primarily award bachelor’s degrees, have similar admission standards, provide similar programs of study, and mostly serve similar types of students.

Yet there are three important differences. One, FAU enrolls a larger proportion of lower- and moderate-income students (39%) than Lynn (23%). Two, FAU has significantly lower annual net cost ($12,605) than Lynn ($34,863). And three, FAU students have a higher median salary ten years after graduation ($43,200) than those at Lynn ($39,300).

As table 1 demonstrates, these differences mean that it takes drastically less time for FAU students to recoup their educational investments than Lynn students—2.5 years versus 8.4 years. And this is especially relevant because those who attend FAU tend to come from less affluent homes than peers at Lynn.

Table 1. Price-to-Earnings Premiums for Florida Atlantic University and Lynn University

In this way, institution-level PEPs provide students with a birds-eye view of how they may fare at one institution in comparison to another. Yet there’s also, of course, PEP variation between programs within each institution, with some allowing students to pay down their educational costs off faster than others. So prospective students should consider that, too.

For lawmakers, however, PEPs are especially important. Our study revealed that there are over 440 institutions that leave the majority of students earning less than a high school graduate in their respective states—meaning they provide a negative return on investment. Yet these schools remain accredited and eligible to receive billions in government subsidies every single year. This should stop. And Price-to-Earnings Premiums can help make that happen if lawmakers use them in a few smart ways:

- Make this information readily available to students through their main college search websites, such as the College Scorecard. This would allow prospective students to gain a better understanding of their likely economic return before they enroll.

- Provide this information to institutional administrators for each program that they offer, so that they can better determine which fields of study either cost too much, lead to insufficient earnings, or both. As we’ve seen in the past, when institutions have been provided with program-level data, they’ve responded by shuttering hundreds of programs that were identified as providing limited value relative to their cost.

- Hold institutions accountable for the outcomes of their students. Without a better accountability system in place to ensure that students are actually left better off financially, taxpayers will continue to allocate billions in government subsidies to low-performing institutions, even though there is no economic benefit for students who attend.

So is college still worth it? Yes, most of the time, pursuing a postsecondary credential definitely pays its dividends. However, these two studies from the Fordham Institute and us at Third Way show that not every institution or credential is created equal. Attending a specific college can have a huge impact on how quickly students will be able to recoup their educational investment. And in some cases, they may experience no economic premium for their credential whatsoever. Furthermore, the value of a credential can vary substantially depending on the type of program, where students live, and their race and ethnicity.

Without more information made available on the economic premium of attending college, many students may still end up pursuing credentials that show limited value. Likewise, if policymakers don’t do a better job of holding institutions accountable for the outcomes of their students, billions in taxpayer dollars will continue to flow to schools that ultimately show little to no return on investment.