Here in Fordham’s pages, I’ve previously written about the challenge of Covid-19 learning losses at the macro level. In this article, I focus on the micro level.

According to an October Pew Research poll, 65 percent of parents are now very or somewhat concerned about their children falling behind in school as a result of disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak.

Their worries are fully justified. Analyses by McKinsey, NWEA, CREDO, and the OECD all agree that Covid learning losses—the amount of progress students are making compared to the progress they would have made if not for the pandemic—are likely very large. And with a growing number of students now facing a return to remote learning, their losses will only grow larger.

What is the probability these losses will be recovered without major changes in the way school districts operate?

Let’s look at the example of math learning losses in Jefferson County, Colorado, the nation’s thirty-sixth largest school district, and where I live.

The population of Jeffco, as we call it, is relatively educated and affluent. Forty-four percent of residents over age twenty-five have at least a bachelor’s degree, and the median household income is $79,000. Only 30 percent of Jeffco schools’ 84,000 students are eligible for free and reduced lunch

Colorado’s last state test results are from Spring 2019. Based on students’ scores on the Colorado Measures of Academic Success (CMAS) assessment, they are categorized as not meeting, partially meeting, approaching, meeting, or exceeding the state’s English language arts and Math standards.

Statistically, the dividing line between less than and more than one standard deviation below the cut score for meeting state standards lies about in the middle of the range of scores in the “partially meets” category.

Keep that in mind.

On the 2019 CMAS math assessment, 16 percent of Jeffco students in grades three through eight did not meet state standards, 18 percent partially met them, and 24 percent were approaching them. In total, 58 percent failed to meet or exceed them. In terms of standard deviations, about 25 percent were more than one standard deviation below the state standard cut score, and 33 percent were less than one standard deviation below it.

What percentage of these students will graduate from high school ready for college or a career? National research studies provide a basis for forecasting the answer to this critically important question.

In ACT Inc.’s research report “Catching Up to College and Career Readiness,” analysts provided two estimates, based on national data.

In math, ACT found that 46 percent of fourth graders who were less than one standard deviation below the cut score for meeting state standards caught up and met state standards in eighth grade. Of the students who were more than one standard deviation below, only 10 percent caught up.

By eighth grade, only 19 percent of students who were less than one standard deviation below the cut score for meeting state standards caught up and met the ACT’s benchmark for college and career readiness in twelfth grade. Of the students who were more than one standard deviation below, just 3 percent caught up.

Two other studies shed light on why so few students catch up.

In “Performance Trajectories and Performance Gaps as Achievement Effect Size Benchmarks for Educational Interventions,” Harold Bloom, Carolyn Hill, Alison Rebeck Black, and Mark Lipsey measured the average grade-to-grade achievement gains in terms of effect sizes (the higher grade score minus the lower grade score, divided by the standard deviation of scores). For example, from grade five to grade six, the effect size was 0.41 standard deviations.

Across all grades, the median grade-to-grade gain was 0.32 standard deviations.

In “Interpreting Effect Sizes of Education Interventions,” Brown University’s Matthew Kraft analyzed high quality studies (usually randomized control trials) of reading and math interventions in grades one through twelve. The median intervention had an effect size of only 0.10 standard deviations.

In sum, these two analyses show why many of the interventions schools use to help students catch up fail to achieve that goal.

In Jeffco, local evidence mimics these national findings.

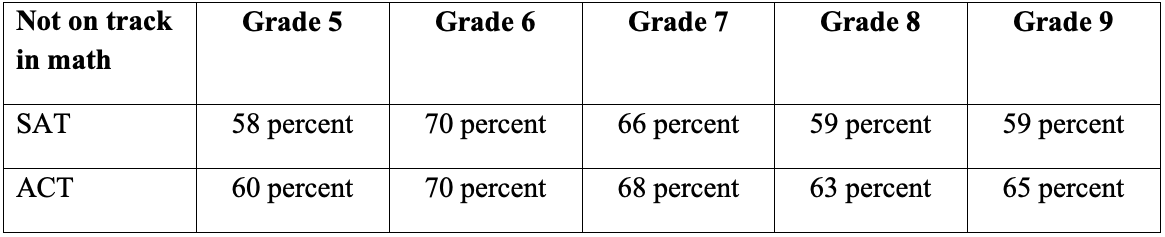

NWEA MAP assessments given in the fall, winter, and spring use predictive analytics to produce a “Projected Proficiency Summary” that estimates the percentage of students in different grades who are not on-track to meet proficiency standards on state assessments and the college-and-career-ready benchmarks on the twelfth grade ACT and SAT tests.

The following table comes from the Winter 2019/2020 MAP. It shows the percentage of Jeffco students in each grade who were not on track to meet the standard in twelfth grade math.

Table 1. Percentage of students in Jefferson County, Colorado, not on track to meet benchmarks for college or career readiness, 2019–20, by test

In sum, before the pandemic arrived, the overwhelming weight of evidence supported the conclusion that, absent extraordinary efforts, it is very difficult for most students to catch up academically once they have fallen behind. For any district, board, or union leader to claim otherwise is grossly misleading.

Now Covid-9 learning losses have made this frightening and depressing situation much worse.

As a result, there are growing doubts that our students will graduate with the depth and breadth of knowledge and skills the nation needs to power economic growth and reduce inequality in the rapidly evolving twenty-first-century digital economy.

Today, the nation’s 14,000 school district management teams, boards, and teachers unions face what is arguably the greatest challenge in their careers: how to enable their students to recover from large (and still increasing) Covid-19 learning losses at a time when a majority of them were already struggling to catch up and graduate ready for college or a career.

Is there any reason to hope that this challenge can be met? Let’s look at three ideas that have been put forward.

In Jeffco, I’ve heard district leaders tell their board and the public that “based on teachers’ formative assessments of students’ learning losses, they will develop customized learning plans to fill the gaps.”

They neglected to mention that researchers have repeatedly found that differentiated instruction is extremely difficult for most teachers to implement—and that, because of this, its use typically produces minimal improvements to student achievement results.

For examples, see, “Differentiation Doesn’t Work,” by Jim Delisle in EdWeek, as well as “Changing the Odds for Student Success,” by Bryan Goodwin from McREL, who notes that, “to date, no empirical evidence exists to confirm that the total package of differentiated instruction (e.g., conducting ongoing assessments of student abilities, identifying appropriate content based on those abilities, using flexible grouping arrangements for students, and varying how students can demonstrate proficiency in their learning) has a positive impact on student achievement.”

The second idea was set out in a recent letter to president-elect Biden by Johns Hopkins University’s Bob Slavin, who proposed “a plan to provide up to 300,000 well-trained college-graduate tutors to work with up to 12 million students.”

In Jeffco, this would not be cheap. Assuming just students who did not meet, or only partially met, state math and English language arts standards on the 2019 CMAS received tutoring, 525 tutors would be needed, based on best practice guidelines for implementing the Multitiered System of Supports approach (MTSS). Even if those tutors are paid just half of what the average Jeffco teacher makes (a big if), the additional cost would be $22 million per year.

Let’s assume the use of these tutors would be based on the MTSS process. John Hattie’s meta-analysis research estimates a very large 1.07 effect size for MTSS. However, because Hattie uses a wider range of studies than Kraft, the latter’s focus on Randomized Control Trials would likely estimate a much smaller effect size.

Let’s assume MTSS would address the needs of students in grades two through eight, who on last winter’s NWEA Math MAP test were projected to be in the lowest two categories on the spring CMAS assessment.

Those 5,900 students in the lowest category would be receive Tier 3 MTSS interventions, meeting with a teacher or tutor in groups of two for forty-five-minute sessions, five days a week, for thirty-two weeks.

The 9,071 students in the “partially meets” state standard CMAS category would be receive Tier 2 MTSS interventions, meeting with a teacher or tutor in groups of six for forty-five-minute sessions, three days a week, for sixteen weeks.

Note that Covid-19 learning losses since last winter would very likely require a substantial increase in the number of students who would need MTSS interventions. But for now, let’s use the data we have available.

Assuming tutors work eight hours per day, 276 of them would be required just for math, and another 259 would be needed for reading interventions.

If the teachers union agreed that these tutors could be paid at half the average $80,000 cost (salary and benefits) to employ a Jeffco teacher (a big if), and assuming qualified tutors could be found, implementing MTSS in Jeffco would cost $22 million per year (and likely much more).

The third idea comes from former New York State Commissioner of Education David Steiner, who is also now at Johns Hopkins: “Acceleration, Not Remediation.” As Steiner describes the approach, “Teachers do not water down curricula for struggling students. Instead, they focus on expediting their growth and filling in any gaps in knowledge or skills, all while teaching them grade-appropriate content on a daily basis.”

The problem with this approach is that, to a significant extent, the effectiveness of district-wide acceleration very likely depends on the existence of a common, integrated, knowledge-rich curriculum.

Having launched the EngageNY curriculum, Steiner certainly understands its powerful impact and how it facilitates acceleration (and many other benefits). So too does his JHU colleague Ashley Berner, who found the same effects when she studied (and later contributed to) the Provincial Curriculum in Alberta.

Unfortunately, districts like Jeffco don’t have a common, high quality curriculum. Instead, Jeffco’s radically decentralized system that lets 150 principals independently choose curricula for their schools has been strongly criticized. Implementing a common district-wide curriculum would also take time that too many students don’t have left to catch up.

As someone who has spent much of his career doing turnarounds, I well know that in these circumstances school districts must avoid two temptations.

The first is the belief that business as usual will be sufficient. I suspect that in too many districts, with their history as effective monopolies that rarely fire people for poor performance, this is the path they will follow. And their students will never recover their Covid-19 learning losses, and as a result will pay a lifetime price.

The second temptation is to delay taking action while continuously searching for and debating the ideal solution, instead of aggressively implementing one that is good enough. Given that school districts don’t fear going out of business, and few of their management teams could be described as agile, I fully expect that many will go down this path. Their students will also pay the price.

If it were up to me, I’d simultaneously pursue both tutoring and acceleration. There are good arguments for both, and they are complementary.

To be sure, implementation would be ugly—but that’s just the nature of turnarounds. Given the solutions that have been offered to the national Covid-19-learning-loss crisis, this seems like the one that is most likely to work.

It remains to be seen whether, in this hour of national need, district management teams, boards, and unions will have the foresight and courage to overcome longstanding obstacles and speedily implement the difficult changes needed to recover these learning losses and dramatically improve K–12 results.

But make no mistake: The stakes we face—for our children, employers, and nation—are extremely high.