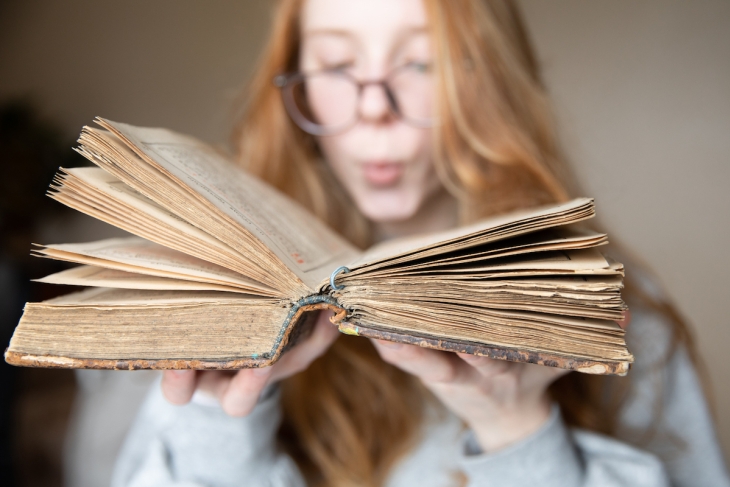

My students caught me smelling an old book once. While they were silently reading one day, I noticed a tattered book on the shelf. So what did I do? Following deep instincts, I pulled it down, cracked the spine, and breathed deeply. “Mr. Buck, what are you DOING?!” I turned around to find the whole class staring at me. To explain myself, we passed around the haggard thing, everyone taking a sniff of that singular, old-book aroma. Some kids got it. Others didn’t. If you know, you know.

Unfortunately, old books have fallen out of favor. For example, the School Library Journal published a recommended list of books to remove from summer reading lists, including Shakespeare, 1984, To Kill a Mockingbird, and other classics. To replace them, the school librarians recommended modern young adult (YA) fiction. At its national conference, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) boasted a slate of sessions on YA fiction and modern media literacy. Popular publications directed at teachers emphasize the need to do away with those stuffy old classics beloved by generation after generation and replace them with new, shiny books.

At the extreme end, books themselves are under attack, cast as relics. NCTE demands that we “decenter book reading and essay writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education,” opting instead for TikTok videos, memes, and gifs. Decades ago, Henry Giroux, deemed by some to be one of the most influential modern education scholars, advanced this same argument and implored teachers to criticize “official texts” and instead use “alternative modes of representation” such as video, photography, and pop culture imagery. The influential #DisruptTexts movement, which recently partnered with Penguin Random House to publish guides for teachers, goes so far as to call the “written word” itself an aspect of “white supremacy culture.”

There are, to be sure, countless considerations to weigh when choosing this or that book for inclusion on the curriculum: age appropriateness, difficulty, character complexity, historical significance, variety of topic and genre, among others. A book’s age is one such factor—but it’s essential that students have opportunities to read great old books not just because they’re great but also because they’re old.

First, old books provide teachers with more opportunities to teach historical knowledge. When I read Frederick Douglass’s autobiography with my students, they concurrently learned about chattel slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation, slave songs and spirituals, the Antebellum South, and the Civil War. A piece of young adult fiction, where the youthful protagonist cavorts around modern America, provides no such opportunity; students already know the context. As our understanding of the connection between content knowledge and reading comprehension grows, old books have a distinct benefit.

Second, old books also familiarize students with archaic language. Taking the time to parse through Shakespeare or Chaucer models for students the practices they need to parse through dense, unfamiliar prose. In college and the workplace, many students will face scientific abstracts, primary source documents, essential civic texts such as the Declaration of Independence, and dense formal reports. Old literature builds the stamina and habits students need to face these readings independently.

Third, if we value exposing our students to opinions and cultures different from their own, then there’s nothing quite as strange to us moderns as something old. Want to expose students to a thoughtful critique of the American system of government? Nothing would quite skewer our modern pretentions quite like excerpts from the monarchist Edmund Burke—providing us a better understanding of both the benefits and drawbacks of modern, liberal, democratic capitalism.

Despite the seeming cultural chasm between my inner-city students and myself, we actually shared many priors and unspoken dogmas about the rights of man and the purpose of government, and our cultures resembled each other’s far more than the Victorian aristocracy or soot-covered London of Brontë and Dickens. Old books can shake us from the bias of the present.

Finally—and here I slide from mere age to status as “classics”—old books have proven themselves worthy before the toughest critic there is: time. G.K. Chesterton famously quipped that “tradition is the democracy of the dead.” Classics and traditions last precisely because multiple earlier generations have agreed that this or that book is worth reading. What’s popular now may prove inferior with time. How many movies bust the box office only to fade into memory within a year? But class time is a precious commodity, allowing English teachers only a handful of books to read every year. Reading old books increases the odds that worthwhile books are chosen as time has largely sifted and winnowed the gold from the dross.

“What books should we read with kids?” is an important question and a storied argument. Writing The Republic back in the fourth century B.C., Plato spilled much ink discussing which tales are right and proper for a child to read. And underneath these quibbles over which books to read is a more fundamental question: Does the past have anything of value to teach the present?

The aforementioned #DisruptText movement suggests that what’s old is inherently “highly problematic.” We must wipe old books from our curriculum like we topple statues of everyone from Confederate generals to Abraham Lincoln. Age and antiquity are not valued but questioned. If teachers must read classics with students, they should do so through “critical lenses,” with a red pen in hand, deducting points from Harper Lee or Edgar Allen Poe for racism or sexism, scribbling over our past with the arrogance of the present.

This is utterly misguided. In old books we discover the great and beautiful literature that most eloquently distills the human experiences and expresses the ideas worth knowing, the heroes and villains of histories worth emulating and fearing, and the events that shaped our society. We discover that human nature hasn’t changed in centuries and the themes buried in Beowulf or the Gilgamesh—however fantastical the stories—aren’t so different from today. We may well also find some troublesome content, but it provides opportunities for discussion and instruction about how society has improved and can still. What’s more, if we judge the past by modern pieties, no one, not even Martin Luther King Jr. or Gandhi for goodness’ sake, will survive.

The argument over what books to read with students has raged from Plato through the canon wars of the ‘80s and ‘90s until now. I’m not suggesting we read only old books with students. But as they come under attack, it’s worth remembering that old books have far more to offer us than a unique olfactory experience, and so it’s imperative that we read and enjoy them with our students.