Expanded Measures of School Performance

Why broader=better

In anticipation of an ESEA reauthorization, policymakers are beginning to rethink which factors should be included in federal school-performance reporting. Enter this latest from RAND, which pushes the discussion along by explaining how states, districts, and other countries report school performance. At the state level, there are currently twenty jurisdictions that publish their own school ratings in addition to federal AYP. While the rating systems vary in detail, they all strongly rely on student testing—using assessment scores in subjects beyond ELA and math (usually science and history), tests weighted on a continuum (rather than a pass-fail mark), and ACT or AP scores (at the high school level). RAND analysts see merit in these metrics, but also push for expanding them beyond such “student outcome data” to assess the whole school culture. To that end, RAND showcases districts and states reporting school-culture indicators (like teacher and student satisfaction) and emotional, behavioral, and physical health indicators (like suspensions). Why is this necessary? As the authors aver, it is widely accepted that NCLB’s emphasis on AYP forced schools and districts to overemphasize testing. Using these expanded school-performance indicators might encourage schools to prioritize college and career readiness, school safety, civil-mindedness, and student health. While RAND is right to say that school-based accountability needs to be rethought, their push for adoption of such a broad slate of measures at the federal level is wrong-sighted. That’s a responsibility best left to the states. Thankfully, as this report points out, many have already picked up that torch.

Heather L. Schwartz, Laura S. Hamilton, Brian M. Stecher, and Jennifer L. Steele, “Expanded Measures of School Performance” (Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation, 2011).

Four months ago, Michael Horn and Heather Staker released a white paper, “The Rise of K-12 Blended Learning.” In it, they warned policymakers of the need to support blended learning—education that splits students’ time between the teacher-led classroom and the digital realm—lest it get stymied by current statutes around seat time, class sizes, life-long teacher contracts, etc. This follow-up paper profiles forty organizations engaged in blended learning of some sort, offering specifics to readers seeking a clearer picture of what blended learning actually looks like for the student and teacher. Along with this framing, the paper offers some smart, concrete policy recommendations to push for easier expansion of the blended-education approach. Some have been voiced in other reformer circles—things like relaxing “highly qualified teacher” mandates (to bring content experts into online classrooms) and completing the transition to the Common Core (to avoid tension between them and state standards). Others are out-of-the-box, but merit serious consideration. For example: those programs able to educate students for less money than the state allotment should be allowed to bank the extra funds in education savings accounts, from which students may pull to pay for tutoring, college tuition, and the like. As blended-learning policy and understanding begin to take shape, this paper—and the original in the series—do well to frame the issue.

Heather Staker, “The Rise of K-12 Blended Learning: Profiles of emerging models,” (Mountain View, CA: Innosight Institute, May 2011).

This World Bank paper looks beyond our borders to determine the marginal loss of income and equity associated with slower rates of human-capital accumulation in the developing world. In layman’s terms (though the dense economic paper never affords them to the reader): How much does each additional year of schooling affect a country’s economic growth and social equity? Using a new data set, the paper looks at 146 developing nations and draws a few interesting conclusions. First, the authors conservatively estimate a 7 to 10 percent average per capita income gain for each additional year of schooling, as well as a societal-inequity reduction of 1.4 points on the Gini index. Further, countries whose average educational attainments have reached the level of basic literacy (i.e., they’ve moved from five to six attained years of schooling) see a net increase of 15.3 percent to their per capita income. Comparing Pakistan and South Korea, the paper reports that, in 1950, both countries had similar per capita incomes ($643 and $854 in constant dollars, respectively). But as South Korea’s educational attainment rose—by 2010 it had reached 11.8 years, dwarfing Pakistan’s 5.6 years—so did its income level. In 2010, South Koreans, on average, made $19,614 compared to Pakistan’s $2,239. As the authors are quick to remind, there are many caveats associated with research of this nature (the effect of externalities, the self-employed, whether a country simply strikes oil or a gold mine, etc.). But the correlations cannot be discounted and lessons for the United States still remain, as some state and city attainment rates fall far below their peers—and as the variant quality of the education doled out leaves some Americans years behind.

Harry Anthony Patrinos and George Psacharopoulos, “Education: Past, Present, and Future Global Challenges,” (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Human Development Network, March 2011).

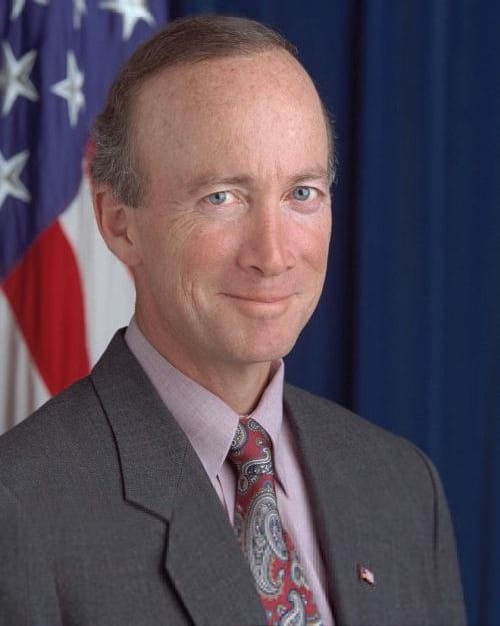

At first blush, it would appear that Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels and former Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings have a lot in common. Both served as cabinet members in the George W. Bush Administration. Both are generally pragmatic centrists. And both hold strong school-reform instincts.

But look closer and the similarities—on federal education policy at least—disappear.

Photo in the public domain

In his big speech last week at the American Enterprise Institute, Governor Daniels went out of his way to stress that school reform—at the state and federal levels—is a work in progress. “The real test for us is dead ahead, and that is to implement these tools,” he said. “I will never stop learning about learning.”

Furthermore, while applauding President Obama and Secretary Duncan for their excellent work on education in general, and Race to the Top in particular, he indicated that a smaller federal footprint is appropriate. Of the federal education bureaucracy, he said, “There’s a lot more of it than we need.” The governor is humble about his accomplishments in Indiana and humble about what the feds can do to fix our schools. “I don’t have magic answers,” he said. “If I did I would have been here giving this talk years ago.”

Secretary Spellings, however, will have none of it. In a new ESEA reauthorization proposal she penned for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce last week, she encourages Congress to double-down on No Child Left Behind and set its sights even higher on what Uncle Sam can do to improve the nation’s schools.

The Chamber’s proposal starts by maintaining almost every detail of NCLB as we know it: State standards and cut scores benchmarked against NAEP; a “date certain” for getting “all students to proficiency in reading and math”; annual measurable objectives with “ambitious” timelines; consequences for (all) schools and districts not meeting their goals. And on and on it goes, traipsing through the greatest hits of NCLB ideas that have been tried and failed.

Photo in the public domain

Give Spellings some credit for consistency. This is, almost verbatim, the same proposal she made a few years ago as Secretary. And yet, she writes, her blueprint builds “on what we’ve learned.” How so? What exactly has she learned? Clearly not that the feds have proven wholly incapable of implementing such key NCLB components as public-school choice and interventions in failing schools. Nor has she recognized that, while Uncle Sam can force states and districts to do things they don’t want to do, he can’t force them to do those things well. And she seems completely blind to all the research showing that prescribing timelines and objectives and mandatory consequences gave states a big fat incentive to maintain a low bar on the standards themselves—and that “benchmarking” against NAEP proved useless to thwarting this trend. If she’s “learned” so much, why hasn’t her position budged an inch since 2001?

Granted, I may be caught up in the Mitch Daniels fervor. If he were to run, to make it past the primaries, and to get elected president (three HUGE ifs), who knows what his actual federal education policy would be. Maybe he’d end up more like Ms. Hubris than Mr. Humble. But for now I’ll just celebrate the fact that a key Republican governor is willing to admit: None of us knows for sure what to do, so let’s give it our best shot and remain willing to change our minds along the way.

| Click to listen to commentary on the Chamber's ESEA proposal from the Education Gadfly Show podcast |

This piece originally appeared (in a slightly different form) on Fordham’s blog, Flypaper. To get timely updates from Fordham, subscribe to Flypaper.

New York City is known for its public-school-choice programs, particularly at the high school level. Students may test into a number of specialized schools (like Stuyvesant or Brooklyn Latin) or try their hand at the lotteries for small learning communities (like Robeson), charter schools (like Harlem Village Academy), and transfer schools (grades 10-12 schools for at-risk students, like Harvey Milk). But a labyrinthine application process, voluminous yet murky information available to parents, and 78,000 students applying for placement each year (for perspective, that’s the total K-12 enrollment in the District of Columbia), means a good number of applicants end up disappointed on “match” day. For the 2010-11 school year, Gotham failed to place about 10 percent of its students in one of their preferred schools (students could select up to twelve), forcing them to enroll at a less desirable neighborhood school. Fundamentally this is a supply problem: Gotham needs more great schools. In the meantime, however, the city’s residents need information aimed at students and parents—especially those from disadvantaged communities—information both about school choices and about how the process works.

“Lost in the School Choice Maze,” by Liz Robbins, New York Times, May 6, 2011.

As Gadfly has matured, he’s become increasingly skeptical of America’s education-governance structure. California is a vivid case-in-point. In the Golden State, a maze of governance arrangements leaves no one in charge and no one responsible for the state’s sub-par student achievement. That role is split among 1,040 elected local school boards, the state superintendent (also elected), the state board of education (appointed by the gov), and the governor himself. Adding to this clamor, voters directly influence education funding through oft contradictory and confusing referenda. A thorny predicament, indeed—and one that shows how an antiquated education-governance structure can be debilitative to student achievement.

“A lesson in mediocrity,” The Economist, April 20, 2011.

In anticipation of an ESEA reauthorization, policymakers are beginning to rethink which factors should be included in federal school-performance reporting. Enter this latest from RAND, which pushes the discussion along by explaining how states, districts, and other countries report school performance. At the state level, there are currently twenty jurisdictions that publish their own school ratings in addition to federal AYP. While the rating systems vary in detail, they all strongly rely on student testing—using assessment scores in subjects beyond ELA and math (usually science and history), tests weighted on a continuum (rather than a pass-fail mark), and ACT or AP scores (at the high school level). RAND analysts see merit in these metrics, but also push for expanding them beyond such “student outcome data” to assess the whole school culture. To that end, RAND showcases districts and states reporting school-culture indicators (like teacher and student satisfaction) and emotional, behavioral, and physical health indicators (like suspensions). Why is this necessary? As the authors aver, it is widely accepted that NCLB’s emphasis on AYP forced schools and districts to overemphasize testing. Using these expanded school-performance indicators might encourage schools to prioritize college and career readiness, school safety, civil-mindedness, and student health. While RAND is right to say that school-based accountability needs to be rethought, their push for adoption of such a broad slate of measures at the federal level is wrong-sighted. That’s a responsibility best left to the states. Thankfully, as this report points out, many have already picked up that torch.

Heather L. Schwartz, Laura S. Hamilton, Brian M. Stecher, and Jennifer L. Steele, “Expanded Measures of School Performance” (Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation, 2011).

Four months ago, Michael Horn and Heather Staker released a white paper, “The Rise of K-12 Blended Learning.” In it, they warned policymakers of the need to support blended learning—education that splits students’ time between the teacher-led classroom and the digital realm—lest it get stymied by current statutes around seat time, class sizes, life-long teacher contracts, etc. This follow-up paper profiles forty organizations engaged in blended learning of some sort, offering specifics to readers seeking a clearer picture of what blended learning actually looks like for the student and teacher. Along with this framing, the paper offers some smart, concrete policy recommendations to push for easier expansion of the blended-education approach. Some have been voiced in other reformer circles—things like relaxing “highly qualified teacher” mandates (to bring content experts into online classrooms) and completing the transition to the Common Core (to avoid tension between them and state standards). Others are out-of-the-box, but merit serious consideration. For example: those programs able to educate students for less money than the state allotment should be allowed to bank the extra funds in education savings accounts, from which students may pull to pay for tutoring, college tuition, and the like. As blended-learning policy and understanding begin to take shape, this paper—and the original in the series—do well to frame the issue.

Heather Staker, “The Rise of K-12 Blended Learning: Profiles of emerging models,” (Mountain View, CA: Innosight Institute, May 2011).

This World Bank paper looks beyond our borders to determine the marginal loss of income and equity associated with slower rates of human-capital accumulation in the developing world. In layman’s terms (though the dense economic paper never affords them to the reader): How much does each additional year of schooling affect a country’s economic growth and social equity? Using a new data set, the paper looks at 146 developing nations and draws a few interesting conclusions. First, the authors conservatively estimate a 7 to 10 percent average per capita income gain for each additional year of schooling, as well as a societal-inequity reduction of 1.4 points on the Gini index. Further, countries whose average educational attainments have reached the level of basic literacy (i.e., they’ve moved from five to six attained years of schooling) see a net increase of 15.3 percent to their per capita income. Comparing Pakistan and South Korea, the paper reports that, in 1950, both countries had similar per capita incomes ($643 and $854 in constant dollars, respectively). But as South Korea’s educational attainment rose—by 2010 it had reached 11.8 years, dwarfing Pakistan’s 5.6 years—so did its income level. In 2010, South Koreans, on average, made $19,614 compared to Pakistan’s $2,239. As the authors are quick to remind, there are many caveats associated with research of this nature (the effect of externalities, the self-employed, whether a country simply strikes oil or a gold mine, etc.). But the correlations cannot be discounted and lessons for the United States still remain, as some state and city attainment rates fall far below their peers—and as the variant quality of the education doled out leaves some Americans years behind.

Harry Anthony Patrinos and George Psacharopoulos, “Education: Past, Present, and Future Global Challenges,” (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Human Development Network, March 2011).