Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Choosing Paul Ryan may have greater edu-implications than you think

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models

Flying squirrels!

Common Core opens a second front in the Reading Wars

Even with limited leverage, Uncle Sam can promote school choice

Choosing Paul Ryan may have greater edu-implications than you think

A little context on racial disparities in suspension rates

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models

The Unintended Consequence of an Algebra-for-All Policy on High-Skill Students: The Effects on Instructional Organization and Students’ Academic Outcomes

The “college for all” klaxon has reached near deafening levels, with much attention paid to ensuring that every youngster has access to the courses necessary to prepare him or her for post-secondary work. But as more kids are flung into mandatory college-prep courses, what happens to the high achievers who already occupied desks in those classes? So asks a new study by Takako Nomi from the Consortium on Chicago School Research. Following six cohorts of Chicago high school students (more than 18,000 in toto, spread across close to sixty schools), Nomi examines the consequences of a 1998 Chicago policy mandating that every ninth grader take Algebra I. First, Nomi finds that this algebra-for-all policy resulted in schools’ opening mixed-ability classrooms—and all but abandoning practices of tracking. The resulting mixed-level classes “had negative effects on math achievement of high-skill students.” To wit: Rates of improvement on math tests slowed for those top-notch pupils placed in heterogeneous classrooms (findings consistent with our own prior work on the topic). All students deserve to be challenged to achieve their full potential. This includes our highest flyers, whose needs are too often subjugated to the grand plans of social engineers.

SOURCE: Takako Nomi, “The Unintended Consequence of an Algebra-for-All Policy on High-Skill Students: The Effects on Instructional Organization and Students’ Academic Outcomes” (Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, published online July 31, 2012).

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

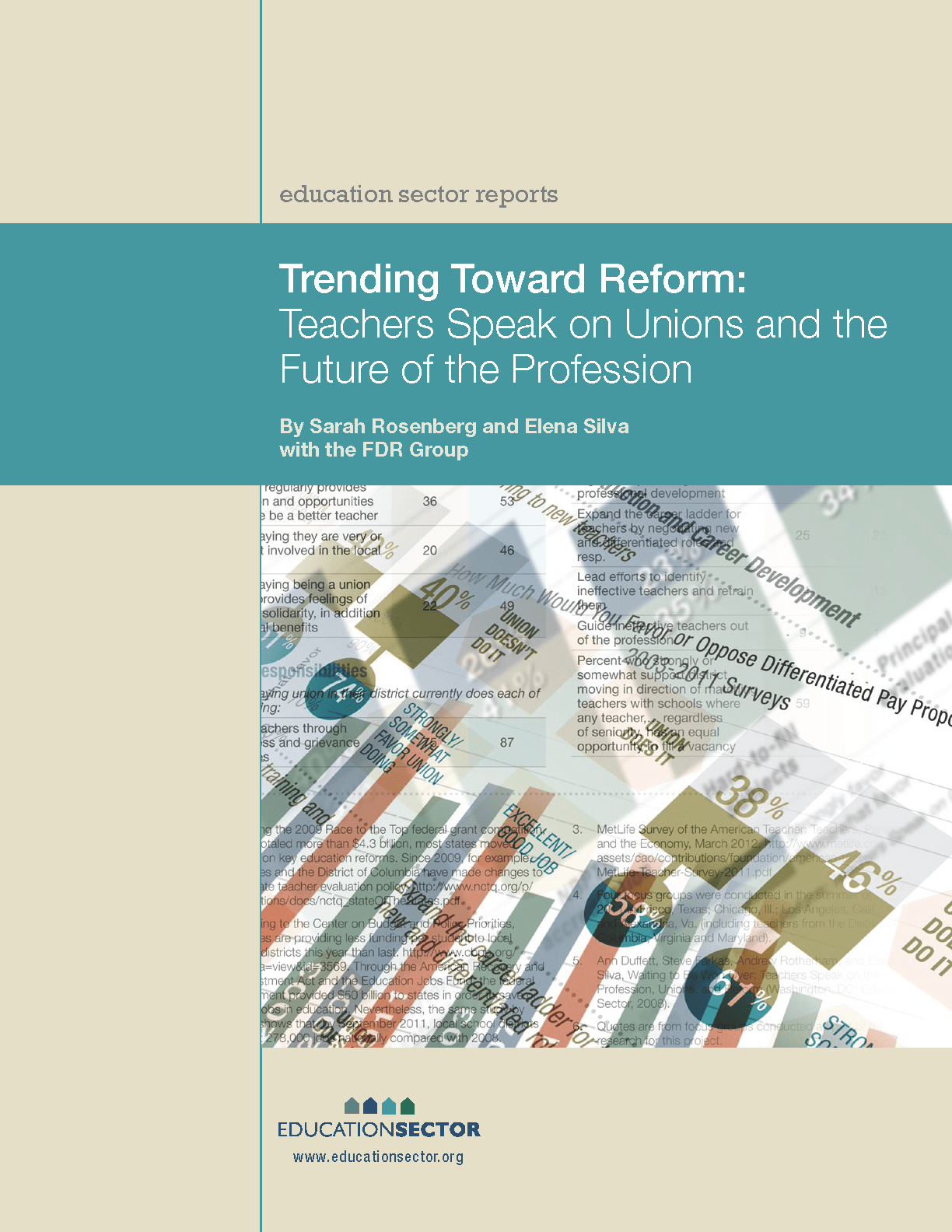

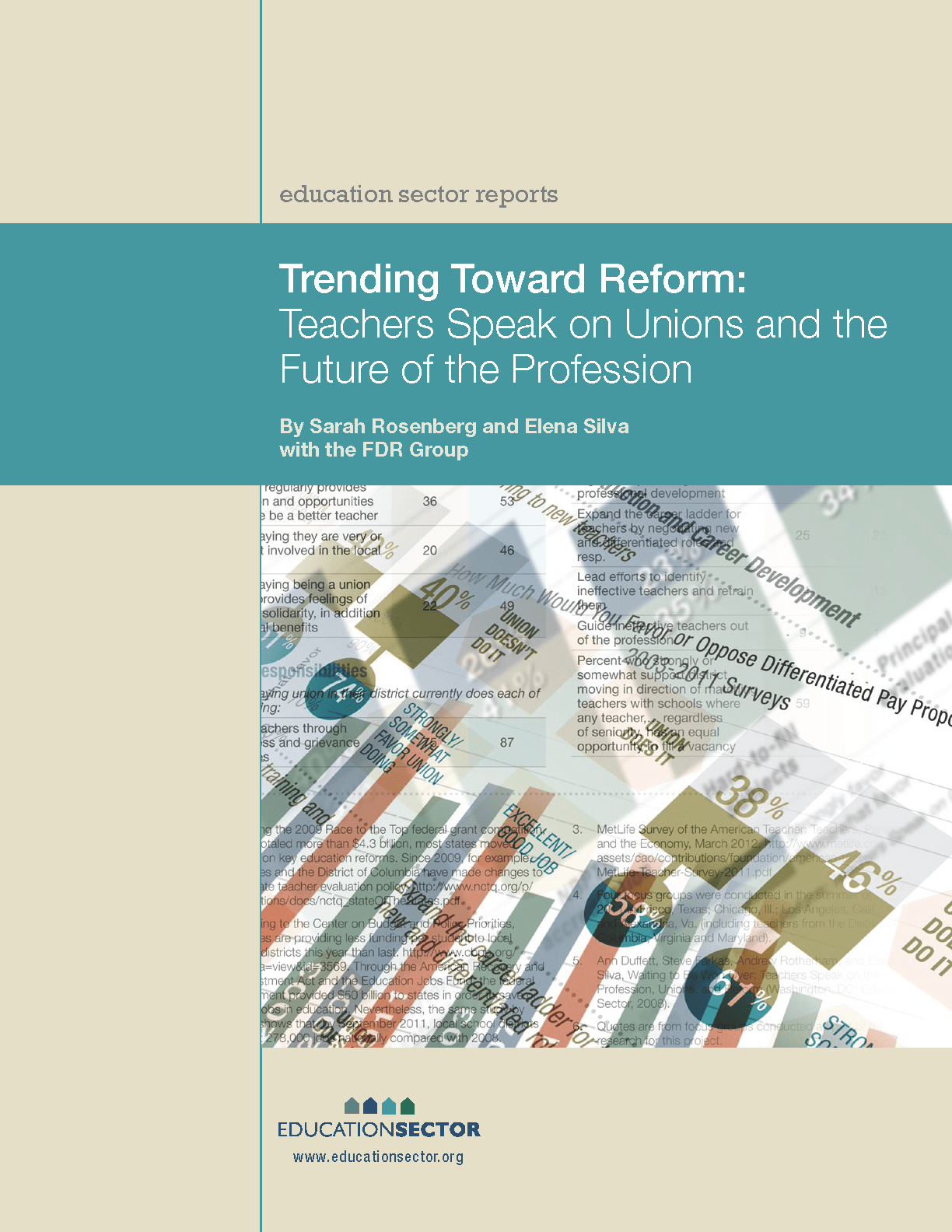

In his seminal (and fundamentally depressing) 2011 book Special Interests, Terry Moe argues that so-called “reform unionism” is a dreamy “have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too vision of the future that flatly misunderstands the fundamentals of union behavior.” Teacher unions, he explains, will forever be Aesop’s oak—structurally resistant to education reform. This latest report from Education Sector surveyed 1,000-plus teachers for their opinions on the condition and role of unionism in U.S. education—as well as their thoughts on teacher policy overall. (This is the third such survey, the first having been conducted in 2003 by Public Agenda, the second by Education Sector in 2007.) Per unions: They are still considered highly by teachers, with three-quarters of all educators (and 70 percent of newbies—those teaching less than five years) reporting that working conditions would be worse without the unions. Levels of pride and involvement in unions are up, too: Since 2007, local unions saw a 10 percentage-point bump in teachers’ reporting that the “union provides feelings of pride and solidarity,” to 41 percent. And how teachers would like their unions to handle education reform is shifting—from Aesop’s steadfast oak to the fable’s malleable reed. Teachers would like to see unions be more involved in formulating evaluation systems and dismissing ineffective educators. This, as a majority (54 percent) of educators agree that growth models are a good way to evaluate teachers (up from 49 percent in 2007). (Though in the minority, teachers whose evaluations already utilize growth models are much more likely to favor this approach—by 18 percentage points.) Ultimately, the report concludes that union viability hinges on whether these entities can maintain a cooperative and reform-minded role. The authors seem to think this is possible. Possible, yes. But highly improbable.

SOURCE: Sarah Rosenberg and Elena Silva, Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession (Washington, D.C.: Education Sector, July 2012).

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Much research contributes to the education-policy debate by adding insights on a particular topic. This latest from the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center, on the other hand, is interesting for what it doesn’t say: notably, that compulsory school attendance (CSA) has any bearing on graduation rates. Authors compared states with a CSA age of eighteen to those with a CSA age of sixteen or seventeen. Overall, the latter group boasts a graduation rate 1 to 2 percentage points higher than the former—findings that hold when controlling for demographic factors as well. What’s more this slight advantage tracks over time as well: Between 1994-95 and 2008-09, states with a CSA age of sixteen or seventeen moved their graduation rates by 3 percentage points. Their counterparts with a CSA age of eighteen saw no improvement in grad rate. (Remember, these are correlated data: They don’t factor in exit-exam difficulty, graduation requirements, etc.) Further, from a policy perspective, the authors find that few states are able to ensure compliance with mandated changes to CSAs. Which makes one wonder: If compulsory school attendance doesn’t move the needle on graduation rates (and, in fact, is associated with states with lower rates of high school completion) and it isn’t feasibly enforced, why have policymakers—President Obama included—made it such a focal issue?

SOURCE: Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst and Sarah Whitfield, Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy (Washington, D.C.: Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, August 2012).

Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models

The figure is staggering, almost unbelievable: 130 percent. That’s the amount by which districts could increase the pay of excellent teachers—without upping class sizes and within current budgets—according to three financial-planning briefs from Public Impact (PI). Each brief describes one model in depth: multi-classroom leadership (master teachers, with the help of aides, educate larger groups of students), elementary-subject specialization (educators teaching either math-science or ELA-history to more pupils), and effectively utilizing digital learning (what PI calls the “time-technology swap”). Each plan centers on PI’s notion of the “opportunity culture,” which allows educators to mount a career ladder based on excellence, leadership, and student impact. And each brief offers: an overview of the cost-saving model, a comparison of savings and cost factors, and scenarios that explain how the model may affect budgets based on a number of inputs (e.g., decisions on how widely to spread excellent teachers and quality of original teaching force). For example, in the multi-classroom leadership approach—which generates by far the most savings—schools can expect to save about $550 per pupil by asking multi-class teachers to lead four classes with three others. These ideas make a ton of sense; unfortunately, common sense rarely rules when staffing American public schools. Gadfly suspects he’ll find these innovative models in action in charter schools long before school districts—and the unions—allow them in traditional public schools.

SOURCE: Public Impact, "Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models" (Chapel Hill, NC: Public Impact, July 2012).

Flying squirrels!

After a week’s hiatus, Mike and Rick catch up on the Romney-Ryan merger, creationism in voucher schools, and the ethics of school discipline. Daniela explains teachers’ views on merit pay.

Amber's Research Minute

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession by Sarah Rosenber and Elena Silva with the FDR Group - Download the PDF

Ten Years After NCLB: Is the GOP Moving Forward, Backward, or Sideways on Education?

What a difference a decade makes. For all the debate around vouchers and student loans, perhaps the most striking element of Mitt Romney's education agenda is how much it differs from the approach of No Child Left Behind, the defining policy of the George W. Bush years. That does not mean, however, that other Republicans necessarily agree with it. The GOP stance on education, and particularly federal education policy, is clearly shifting. But in any clear direction? And for the better?

To examine those questions, the Fordham Institute will bring together two former GOP education secretaries to discuss the Republican Party's direction on this vital issue.

Common Core opens a second front in the Reading Wars

A version of this post originally appeared on the Shanker Institute blog.

Up until now, the Common Core (CCSS) English language arts (ELA) standards were considered path-breaking mostly because of their reach: This wasn’t the first time a group attempted to write “common” standards, but it is the first time they’ve gained such traction. But the Common Core ELA standards are revolutionary for another, less talked about, reason: They define rigor in reading and literature classrooms more clearly and explicitly than nearly any of the state ELA standards that they are replacing. Now, as the full impact of these expectations starts to take hold, the decision to define rigor—and the way it is defined—is fanning the flames of a debate that threatens to open up a whole new front in America’s long-running “Reading Wars.”

A new front opens on a war worth waging. Photo by Ben Stephenson. |

The first and most divisive front in that conflict was the debate over the importance of phonics in early-reading instruction. Thanks to the 2000 recommendations of the National Reading Panel and the 2001 “Reading First” portion of No Child Left Behind, the phonics camp has largely won this battle. Now, while there remain curricula that may marginalize phonics and phonemic awareness, we see few if any that ignore these elements completely.

But the debate over phonics is limited to the early grades. There remain important divisions over how best to devise curricula and teach literature in the years that follow, and minimizing (or papering over) these divisions has been central to most standards-setting efforts. After all, the “grand compromise” of standards-driven reform has always been: States get to define what students should know and be able to do at each grade, but teachers retain the flexibility and autonomy to decide how best to assist all of their pupils to reach those goals. And standards-setters have been loath to provide too much guidance to curriculum developers, particularly in ELA.

Common Core is no different in that regard. Page six of the CCSS ELA standards states:

The Standards define what all students are expected to know and be able to do, not how teachers should teach…

Yet in a field like this, where the content is ill-defined and its substance changing—sometimes dramatically—from early elementary to high school, where is the line drawn between the “what” and the “how”?

Most state-level ELA standards have defined the “what” as the skills and behaviors that great readers share. These expectations have therefore described only very broadly what students should actually be able to do, and they’ve only hinted at how teachers should define content and rigor at each grade level.

Sounds marvelously adaptable, yes, but the actual result was that most state ELA standards were vague and virtually meaningless directives that led to the kind of low-level reading assessments and “teach to the test” preoccupation that has plagued far too many classrooms for the past decade.

Enter the Common Core.

Like the state ELA standards that preceded them, the CCSS describe the skills and behaviors that great readers and writers exhibit at each grade level. But, in an effort to define the rigor more clearly than their predecessors, the Common Core standards specify that the sophistication of what students read is as important as the skills they master from grade to grade. To that end, Standard 10 clearly asks that all students be exposed to and asked to analyze grade-appropriate texts, with scaffolding as necessary.

No one likes war, but this is an important fight that’s worth having. And it’s one that has been put off for too long.

This seemingly innocuous directive—to read appropriately complex texts and to use scaffolding to help struggling students understand what they’ve read—is perhaps the most revolutionary element of the Common Core standards. For the first time, the standards guiding curriculum and instruction in forty-six states plus D.C. clearly define what it means for an ELA curriculum to be aligned to the level of rigor necessary to prepare students for college and beyond.

But this clarity means picking sides. There have long been two very different schools of thought about the best way to organize curriculum and instruction in literature. On one side are those who believe that reading comprehension will improve if teachers assess students’ individual reading levels and give them a bevy of “just right” books that will challenge them just enough to nudge them to read slightly more challenging texts. Yes, teachers do provide some guidance and instruction, but that instruction is limited. In essence, the book choice is leveled to meet the student where he or she is; the “heavy lifting” of reading is placed squarely on the students’ shoulders.

On the other side are those who believe that reading comprehension improves as domain-specific content knowledge deepens and students are exposed to increasingly complex literature and nonfiction texts. Here the role of the teacher is more pronounced, and instruction more explicit. The instruction, not the text, is scaffolded to meet the students where they are.

Until now, the vagueness of state standards allowed teachers to decide where their instruction would fall, and to choose between programs like “Great Books” or “Junior Great Books,” which put the emphasis on reading and analyzing rich and complex literature, or programs like the Teachers College Reading and Writing Workshop or Heinemann’s Fountas and Pinnell Leveled Literacy System, which focus on assessing students’ reading levels and assigning “just right” books for them to read.

If you are to take the Common Core at its word—that the sophistication of the text is equally as important as the skills that students master—then it will be increasingly difficult for publishers of curricula that focus on matching books to readers, rather than scaffolding instruction to meet their needs, to claim that their materials are truly aligned with the new standards. It’s a sweeping change that holds enormous promise for improving the quality of ELA curriculum in America’s classrooms.

This is also a debate that, until now, has mostly been waged in classrooms and among curriculum developers, outside the scope of state standards and below the radar of the national press. But with the specific guidance in the Common Core state ELA standards, the critical question of how to define rigor in an ELA classroom now has front lines in all but four jurisdictions. And while some believe that, by wading into this debate, the Common Core has violated the principles of the “grand compromise” of standards-driven reform, others believe that this guidance gives these standards more clarity and purpose than teachers have had for years.

No one likes war, but this is an important fight that’s worth having. And it’s one that has been put off for too long.

Even with limited leverage, Uncle Sam can promote school choice

Mitt Romney’s plan to voucherize (though he doesn’t call it that) Title I and IDEA has considerable merit—but it’s not the only way the federal government could foster school choice and it might not even be the best way.

It’s not a new idea, either. I recall working with Bill Bennett on such a plan—which Ronald Reagan then proposed to a heedless Congress—a quarter century ago.

It had merit then and has even more today, if only because the passing decades have brought so much more evidence that the original versions of these programs don’t do much for kids. As America nears the half-century mark with Title I, we can fairly conclude that pumping all this money into districts to boost the budgets of schools serving disadvantaged students hasn’t done those youngsters much good by way of improved academic achievement, though of course that cash has been welcomed by revenue-hungry districts (and states). Evaluation after evaluation of Title I has shown that iconic program to have little or no positive impact, and everybody knows that the No Child Left Behind edition of Title I—which encompasses AYP and the law’s accountability provisions—hasn’t done much good either. It has, however, yielded an enormous number of schools that we now know, without doubt, are doing a miserable job, particularly with disadvantaged kids. Yet we’re having a dreadful time “turning around” those schools. One may fairly conclude that Title I in its present form isn’t working and probably cannot.

What if these backpacks were filled with dollars for students' educations? Photo by Dell. |

So why not try strapping the money to the backs of needy kids and letting them take it to the schools of their choice? This would help them escape from dreadful schools. It would make them more “affordable” for the schools they move into. It would remove one of the main barriers (the non-portability of federal dollars) that discourages states and districts from moving toward “weighted student funding” with their own money. And it would certainly go a long way to change the balance of power in American education from producers to consumers.

Having said that, a word of caution is needed. In K–12 education, the states are ultimately in charge and few federal initiatives in this realm work nearly as well as intended. (NCLB is again a large, recent, case in point.) Legitimate questions persist about what, exactly, is the federal role in the K–12 sphere, particularly in reforming it. A good case can be made for Washington to generate sound data, safeguard civil rights, support research, and assist with the costs of educating high-risk kids—but setting the ground rules for schools and operating the system is really the job of states. Moreover, the federal share of the school dollar—a dime—isn’t big enough to yield much leverage over how the system works. That’s why the Romney plan is apt to do some good in states (and districts) that want to extend more school choices to their students—the federal dime can join the 90 cents in state and local funds in the kids’ backpacks—but won’t make much difference in places that aren’t willing to put their own resources into this kind of reform.

Similar caveats must be attached to other possible methods by which Uncle Sam could try to foster school choice. Which isn’t to say such possibilities don’t exist. Indeed, I can think of four more opportunities.

First, any number of other existing federal programs could be “voucherized.” Some are small, to be sure, but others are substantial enough to benefit many thousands of kids. The “impact aid” program—for districts with military and other “federal” youngsters—is $1.3 billion. Vocational education (“Perkins Act”) is almost as large. Many billions lurk in sundry “school improvement” and “innovation” programs that could be amalgamated and then placed in the hands of students rather than states and districts. And don’t forget the enormous Head Start program (run by the Department of Health and Human Services).

Second, a handful of programs that already promote school choice—aid to charter schools, the District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program, etc.—could be expanded.

Third, the Education Department could mount a competitive-grant program akin to Race to the Top for states and/or districts that want to engage in more school choice. (See comment above regarding where the Romney plan is most apt to work!)

Fourth, Congress could enact Senator Lamar Alexander’s proposed “G.I. Bill for Children,” which would give needy K–12 students grants (in participating states) the equivalent of Pell Grants with which to pay tuition at the private school of their choice. (Essentially the same thing could be done via tax credits, too. I cut my own policy teeth back in the 1970s on the “Packwood Moynihan Tuition Tax Credit” bill—which passed the House but was then killed by feverish public-school lobbying.)

Let me say it again, however. At day’s end, states and districts control 90 cents of the K–12 dollar and Washington is limited in what it can do to override their institutional, political, and constitutional obstacles to school choice. Private schools are also more ambivalent today than they once were about taking government money and the strings that are inevitably attached to it.

But the fact remains that school choice, both the public and the private kinds, is spreading across the land, making clear that a nontrivial number of states and districts are up for this. In such places, Washington can surely help by removing the obstacles that today’s gnarly formulas and rules place on federal dollars that might otherwise accompany state and local monies into kids’ backpacks. And via adroit use of competitive grants and—at least as important—the presidential bully pulpit, Uncle Sam may be able to give a modest boost to the movement to put families, rather than bureaucracies, in control of their children’s education.

A version of this post originally appeared on the RedefinED blog.

Choosing Paul Ryan may have greater edu-implications than you think

Mitt Romney stirred a sleepy August news cycle into action on Saturday with his introduction of Congressman Paul Ryan as running mate. The choice awakened the blogosphere, recharged the mainstream media, and enlivened policy wonks across the political continuum. By allying with an unapologetic champion of smaller government—and deep budget cuts for practically everything that Washington has undertaken—Romney has rewritten the narrative for the rest of this election cycle. As Rick Hess notes, “selecting Ryan signals that the Romney campaign, by choice or by necessity, is going to wind up talking ideology.” It also means that education could yet play a more central role in this election than previously assumed. Consider Obama’s initial response, listing numerous education programs (including Head Start and college aid) that would be cut under the Ryan (now Romney-Ryan) budget. Hess further explains: “Education is where Obama can most cleanly argue that he’s for smart ‘investments’ and not just more borrowing and spending”—and where he can highlight bipartisan support for Race to the Top and his stance on charter schooling. The economy is still the diva of this election cycle. But education—which has been a sixth-tier understudy to date—now has a greater chance of seeing some stage time during the fall campaign.

SOURCE: “Ryan’s VP Nod: What’s It Mean for Education?,” by Rick Hess, Rick Hess Straight Up!, August 13, 2012.

You may also be interested in..."Paul Ryan and the education lobby's suicide march to fiscal oblivian," by Michael J. Petrilli

A little context on racial disparities in suspension rates

Last week the Civil Rights Project reported that black students—especially those with disabilities—are suspended at much higher rates than their peers. But does this mean, as Arne Duncan has intimated, that these youngsters are victims of discrimination? The study found that black students were 3.4 times more likely to be suspended than white students. Jarring indeed. But consider this: Black adults are 5.8 times more likely to be in prison than whites. Yes, you can make a case that our justice system is also racist. But even if that’s so, nobody would argue that eliminating racism and discrimination would remove the disparity entirely. We understand that all manner of social pathologies—poverty, single parenthood, addiction, etc.—disproportionately impact the black community. Turning that situation around is the focus of many school reformers and other social entrepreneurs. In the meantime, however, we are not wrong to expect that those pathologies will lead to higher levels of crime. So it is with school discipline. Considering what many poor, black children are up against, is it really hard to believe that they might be 3.4 times more likely to commit infractions that carry a penalty of suspension from school? As the Civil Rights Project report itself admits, the data do not “provide clear answers” to the question: “Are blacks and others misbehaving more or experiencing discrimination?” That’s an important caveat that Secretary Duncan would be wise to remember.

A version of this analysis appeared on the Flypaper blog.

SOURCE:“Opportunities Suspended: The Disparate Impact of Disciplinary Exclusion from School,” by Daniel J. Losen and Jonathan Gillespie, The Civil Rights Project, August 7, 2012.

Ten Years After NCLB: Is the GOP Moving Forward, Backward, or Sideways on Education?

What a difference a decade makes. For all the debate around vouchers and student loans, perhaps the most striking element of Mitt Romney's education agenda is how much it differs from the approach of No Child Left Behind, the defining policy of the George W. Bush years. That does not mean, however, that other Republicans necessarily agree with it. The GOP stance on education, and particularly federal education policy, is clearly shifting. But in any clear direction? And for the better?

To examine those questions, the Fordham Institute will bring together two former GOP education secretaries to discuss the Republican Party's direction on this vital issue.

Ten Years After NCLB: Is the GOP Moving Forward, Backward, or Sideways on Education?

What a difference a decade makes. For all the debate around vouchers and student loans, perhaps the most striking element of Mitt Romney's education agenda is how much it differs from the approach of No Child Left Behind, the defining policy of the George W. Bush years. That does not mean, however, that other Republicans necessarily agree with it. The GOP stance on education, and particularly federal education policy, is clearly shifting. But in any clear direction? And for the better?

To examine those questions, the Fordham Institute will bring together two former GOP education secretaries to discuss the Republican Party's direction on this vital issue.

The Unintended Consequence of an Algebra-for-All Policy on High-Skill Students: The Effects on Instructional Organization and Students’ Academic Outcomes

The “college for all” klaxon has reached near deafening levels, with much attention paid to ensuring that every youngster has access to the courses necessary to prepare him or her for post-secondary work. But as more kids are flung into mandatory college-prep courses, what happens to the high achievers who already occupied desks in those classes? So asks a new study by Takako Nomi from the Consortium on Chicago School Research. Following six cohorts of Chicago high school students (more than 18,000 in toto, spread across close to sixty schools), Nomi examines the consequences of a 1998 Chicago policy mandating that every ninth grader take Algebra I. First, Nomi finds that this algebra-for-all policy resulted in schools’ opening mixed-ability classrooms—and all but abandoning practices of tracking. The resulting mixed-level classes “had negative effects on math achievement of high-skill students.” To wit: Rates of improvement on math tests slowed for those top-notch pupils placed in heterogeneous classrooms (findings consistent with our own prior work on the topic). All students deserve to be challenged to achieve their full potential. This includes our highest flyers, whose needs are too often subjugated to the grand plans of social engineers.

SOURCE: Takako Nomi, “The Unintended Consequence of an Algebra-for-All Policy on High-Skill Students: The Effects on Instructional Organization and Students’ Academic Outcomes” (Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, published online July 31, 2012).

Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession

In his seminal (and fundamentally depressing) 2011 book Special Interests, Terry Moe argues that so-called “reform unionism” is a dreamy “have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too vision of the future that flatly misunderstands the fundamentals of union behavior.” Teacher unions, he explains, will forever be Aesop’s oak—structurally resistant to education reform. This latest report from Education Sector surveyed 1,000-plus teachers for their opinions on the condition and role of unionism in U.S. education—as well as their thoughts on teacher policy overall. (This is the third such survey, the first having been conducted in 2003 by Public Agenda, the second by Education Sector in 2007.) Per unions: They are still considered highly by teachers, with three-quarters of all educators (and 70 percent of newbies—those teaching less than five years) reporting that working conditions would be worse without the unions. Levels of pride and involvement in unions are up, too: Since 2007, local unions saw a 10 percentage-point bump in teachers’ reporting that the “union provides feelings of pride and solidarity,” to 41 percent. And how teachers would like their unions to handle education reform is shifting—from Aesop’s steadfast oak to the fable’s malleable reed. Teachers would like to see unions be more involved in formulating evaluation systems and dismissing ineffective educators. This, as a majority (54 percent) of educators agree that growth models are a good way to evaluate teachers (up from 49 percent in 2007). (Though in the minority, teachers whose evaluations already utilize growth models are much more likely to favor this approach—by 18 percentage points.) Ultimately, the report concludes that union viability hinges on whether these entities can maintain a cooperative and reform-minded role. The authors seem to think this is possible. Possible, yes. But highly improbable.

SOURCE: Sarah Rosenberg and Elena Silva, Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession (Washington, D.C.: Education Sector, July 2012).

Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy

Much research contributes to the education-policy debate by adding insights on a particular topic. This latest from the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center, on the other hand, is interesting for what it doesn’t say: notably, that compulsory school attendance (CSA) has any bearing on graduation rates. Authors compared states with a CSA age of eighteen to those with a CSA age of sixteen or seventeen. Overall, the latter group boasts a graduation rate 1 to 2 percentage points higher than the former—findings that hold when controlling for demographic factors as well. What’s more this slight advantage tracks over time as well: Between 1994-95 and 2008-09, states with a CSA age of sixteen or seventeen moved their graduation rates by 3 percentage points. Their counterparts with a CSA age of eighteen saw no improvement in grad rate. (Remember, these are correlated data: They don’t factor in exit-exam difficulty, graduation requirements, etc.) Further, from a policy perspective, the authors find that few states are able to ensure compliance with mandated changes to CSAs. Which makes one wonder: If compulsory school attendance doesn’t move the needle on graduation rates (and, in fact, is associated with states with lower rates of high school completion) and it isn’t feasibly enforced, why have policymakers—President Obama included—made it such a focal issue?

SOURCE: Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst and Sarah Whitfield, Compulsory School Attendance: What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy (Washington, D.C.: Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, August 2012).

Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models

The figure is staggering, almost unbelievable: 130 percent. That’s the amount by which districts could increase the pay of excellent teachers—without upping class sizes and within current budgets—according to three financial-planning briefs from Public Impact (PI). Each brief describes one model in depth: multi-classroom leadership (master teachers, with the help of aides, educate larger groups of students), elementary-subject specialization (educators teaching either math-science or ELA-history to more pupils), and effectively utilizing digital learning (what PI calls the “time-technology swap”). Each plan centers on PI’s notion of the “opportunity culture,” which allows educators to mount a career ladder based on excellence, leadership, and student impact. And each brief offers: an overview of the cost-saving model, a comparison of savings and cost factors, and scenarios that explain how the model may affect budgets based on a number of inputs (e.g., decisions on how widely to spread excellent teachers and quality of original teaching force). For example, in the multi-classroom leadership approach—which generates by far the most savings—schools can expect to save about $550 per pupil by asking multi-class teachers to lead four classes with three others. These ideas make a ton of sense; unfortunately, common sense rarely rules when staffing American public schools. Gadfly suspects he’ll find these innovative models in action in charter schools long before school districts—and the unions—allow them in traditional public schools.

SOURCE: Public Impact, "Pay Teachers More: Financial Planning for Reach Models" (Chapel Hill, NC: Public Impact, July 2012).