Betsy DeVos is wrong about accountability for schools of choice

By Chester E. Finn, Jr.

By Chester E. Finn, Jr.

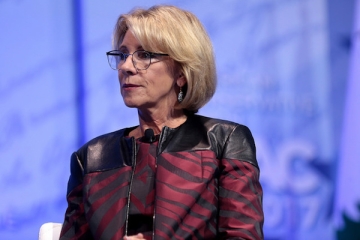

Accountability for schools of choice is a topic forever in the news—and in dispute. The latest combatant is none other than Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who made clear in a recent interview with the Associated Press that she favors letting the market work its will and trusting parents to judge whether a school is worth attending. In this context, she was referring specifically to private schools insofar as they participate in publicly financed voucher or tax-credit-scholarship programs. (Yes, yes, I understand the argument that if it’s done via tax credits it’s not actual public financing. But that begs the political and policy questions that dog such programs and those who want more of them.)

When it comes to charter schools, the Secretary acknowledged that authorizers play a role alongside parents, though she picked the dubious case of Michigan, her home state, to illustrate the point. The Wolverine State certainly has some top-notch authorizers, and they have indeed closed down some failing charter schools, yet the overall track record of Michigan charters is too spotty—at least in the eyes of those who value academic achievement and fiscal probity—to warrant citing it as a stellar example of quality control via authorizing.

Back in June, I unloaded on the authors of a recent CER volume on charters’ “freedom, flexibility and opportunity” because of their support for a market-only accountability system. Indeed, I termed it “idiocy,” and a bunch of folks jumped all over me for using that blunt term. But I also deferred for later the admittedly gnarlier issue of whether the market is sufficient when the schools involved are private yet the funding involved is arguably public.

Later is now, thanks to the AP and Secretary DeVos taking the matter off the table. Here’s what she had to say about it:

I think the first line of accountability is frankly with the parents. When parents are choosing [a] school they are proactively making that choice. And schools are accountable to the parents. And vice versa, the students doing well and working to achieve in the schools. I think it's important for parents to have information about how their students are doing, how they're achieving, how they're progressing. And that kind of transparency and accountability I think is really the best approach to holding schools accountable broadly. It starts with holding themselves accountable to communication of relevant and important information to students and parents about how they are doing. And we know from, that when parents choose and they are unhappy with whatever the school setting is they will choose something different. And that's the beauty of having choices.

Parents as first line of defense, sure, although she appears to trust the schools themselves to equip the parents with the information they need to make competent decisions. There’s no sign of any sort of impartial data source.

But where’s the second line of defense? She never gets around to one, not to anything akin to authorizing in the case of charters or “protective services” or audits in the case of private schools that may be committing educational abuse or financial fraud. (For that matter, she doesn’t even mention such rudiments as health and fire codes.)

For me, this approach just doesn’t cut it, not when we’re talking about publicly authorized and funded programs intended to educate needy children in whose educational success there is a strong public (as well as private) interest. Where’s the school equivalent of the FDA or Department of Agriculture, enabling parents to see the ingredients on a can of beans and to be sure that the chicken in the grocery case is not contaminated with salmonella?

At Fordham, we’ve spilled a lot of ink over this issue in recent years. After much thought, research, and palaver, we’ve ended up firmly attached to a trinitarian approach to private-school accountability in cases of publicly-supported choice programs.

We recommend that states:

We’re painfully aware that this kind of comparability and transparency does not always advance private-school choice in the sense of persuading people that there should be more of it. Several recent evaluations of voucher programs that use such publicly available assessment data—including one sponsored by Fordham—have yielded mixed or negative results in terms of the academic efficacy of participation in such programs.

Sobering, yes, and if we were single-mindedly dedicated—as perhaps Secretary DeVos is—to expanding and extending access to such programs, we might back off from results-linked accountability. In the long run, however, it’s better for choice, for kids, for taxpayers, and for the country’s economic vitality and social mobility that we continue to insist: No school, public or private, is a good school unless its students are learning what they should. And where public policy and public funding are concerned, what kids should learn is a matter of public interest and so are the results that their schools are—or aren’t—producing. It would be wonderful if the parent marketplace were a sure-fire mechanism for gauging and producing those results. Sadly, it simply isn’t. Which is to say, again sadly, Secretary DeVos has this one wrong.

The big news out of this year’s Education Next poll is the sharp decline in support for charter schools, even among Republicans, which is going to leave us wonks scratching our heads for months. But don’t miss the findings on what we used to call “standards-based reform.” Support for common standards has rebounded, with proponents outnumbering opponents three to one. And a strong plurality of Americans want states—and not the feds, and not local school boards—to set academic standards, determine whether a school is failing, and if so, determine how to fix it.

Perhaps not coincidentally, this is precisely where Congress landed two years ago when it passed the Every Student Succeeds Act. Lawmakers pushed key decisions to the states and, in some cases, to local communities. But there were limits. When it came to standards-setting and testing, the feds made it clear that states could not delegate their responsibilities. Uniform, statewide systems are still required, just as they have been for over twenty years.

Alas, someone needs to explain that to Arizona and New Hampshire. While both states deserve plaudits for innovative moves in recent years—Arizona for its excellent approach to school ratings under ESSA, and New Hampshire for its work on competency-based education—they have erred in enacting laws that would let local elementary and middle schools select among a range of options when it’s time for annual standardized testing. That’s bad on policy grounds, and it clearly violates ESSA.

First let’s tackle the substantive concerns. The reason that policymakers have embraced statewide standards and assessments for more than two decades is that they are proven ways to raise expectations for all students. In the bad old days, before statewide standards, affluent communities tended to ask their kids to shoot for the moon (or at least 3s, 4s, and 5s on a battery of Advanced Placement exams), while too many schools in low-income neighborhoods were happy with basic literacy and numeracy. These expectations gaps haven’t disappeared, but they have narrowed. And statewide standards and assessments at least point to a common North Star, plus provide transparency about how close students and schools are coming to achieving college-and-career-ready benchmarks.

The risk with Arizona and New Hampshire’s approach is that some schools will opt for easier tests—and that will exacerbate the expectations and achievement gaps.

As for the legal question, as this brief from Dennis Cariello makes clear, Congress debated whether to allow states to let districts choose among a menu of tests, and decided against it—at least for grades 3–8. It did open the door to such an approach in high school, where kids are already taking lots of other tests. And there’s good evidence that getting everyone to take the SAT or ACT is smart policy. But not for younger students.

To be sure, the testing landscape is going to continue to evolve, and federal policy should be supportive. Already, for example, several states have asked for waivers from ESSA to allow them to give an algebra test to some of their middle schoolers, rather than the regular assessment, so as to avoid double-testing. That strikes me as perfectly reasonable. There’s also ESSA’s “innovative assessments pilot,” which provides space for breaking new ground.

But a general balkanization of standards and testing is not allowed, for good reason. Local control has its place—but, as Americans told Education Next, it also has its limits.

My memory is a little hazy, but I’m pretty sure the first time I heard the term “Nazi” was when I was nine or ten and watching the “Blues Brothers” on TV. All I remember is that the neo-Nazis were having a parade, and getting in the Blues Brothers’ way, and the whole thing was treated as farce. They were clearly a bunch of losers and idiots, not even worthy of fear. They were a punchline, the butt of a joke.

Of course, as I got older, the ugly, evil reality of Nazis, the KKK, and white supremacists became clear to me, thanks in large part to Mr. Klein at Parkway West Senior High School, and his World History and AP U.S. History courses. I’m pretty sure Mr. Klein didn’t just care about making us “college and career ready”; he wanted us to understand the full scope of humanity’s history, both the wonders of our cultural achievements and the depravity of totalitarianism. Today I feel a special sense of gratitude for Mr. Klein, and all his compatriots in social studies departments across the country, who gave us the gift of understanding the beauty, and evil, of which humans are capable.

So it was that the image of a mob of angry white men carrying torches in front of a church in the Old Dominion touched a nerve, and triggered an immune response among Americans far and wide. And that the cowardly attack on peaceful protesters by a homegrown terrorist brought to mind Selma and Montgomery, not to mention Oklahoma City.

Vice President Pence finally said the words appropriate to the horrific events: “We have no tolerance for hate and violence from white supremacists, neo-Nazis or the KKK,” which he called “dangerous fringe groups.” President Trump should say those words himself (update: he more or less just did), should make it clear that these groups are full of losers, that he wants nothing to do with them, that they aren’t welcome in American public life or in the Republican Party or the conservative movement.

And he should tell Americans of all backgrounds, but especially the descendants of slavery and the relatives of Holocaust survivors, that he appreciates the pain and suffering triggered by these idiots, these losers, these terrorists, with their torches and their angry chants. That he understands history and will not let it repeat itself, not on his watch.

As for the rest of us, let’s try in the days ahead to treat each other with a little extra love and compassion. And if you feel despair, read some history, and be reminded that the idiots are a small minority, that most of our fellow citizens have good hearts, and that evil is no match for America.

On this week's podcast, Mike Petrilli, Brandon Wright, and David Griffith discuss Education Next’s new poll and what might be driving the surprising results regarding charter schools and vouchers. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines how dual-enrollment affects college degree attainment.

Bob Blankenberger et al., “Dual Credit, College Type, and Enhanced Degree Attainment,” Educational Researcher (July 2017).

Which teachers remain teaching in their original schools, who transfers to other schools, and who exits teaching altogether obviously has implications for the quality of the teaching workforce. A new study conducted by Tim Sass and Li Feng examines how teacher quality (as measured by value-added data) and teacher mobility are related.

Analysts utilize teacher quality and mobility data in Florida from the 2000–01 school year to 2003–04. Specifically, they use matched student-teacher panel data that includes math and reading teachers in grades 4–10, for whom they have current and prior-year student achievement data.

They find that, for both math and reading, the average quality of teachers who stay at their initial schools is higher than teachers who switch schools within their initial district, move to another district, or leave public school teaching altogether. Moreover, better-than-average and worse-than-average teachers (those in the top and bottom quartiles, respectively) both have a higher likelihood of leaving teaching compared to middling teachers. Analysts say this is consistent with “schools losing their best teachers to more attractive outside options and losing their worst teachers who may be better suited to other occupations.”

They also find that, as the share of peer teachers with more experience, advanced degrees, or professional certification increases, the likelihood of moving within the district decreases. This suggests that peer teachers with better qualifications “may be more likely to provide positive spillovers or otherwise enhance the work environment.”

Next, they find that teachers overall tend to move to schools where students have higher achievement, a smaller fraction of students are black, and a smaller proportion of students are low income. Digging deeper, their results show that teachers who move tend to go to a school where the average teacher quality is like their own. For instance, the fraction of top-quartile movers hired by schools whose faculty is in the top quartile is much higher than that of schools whose faculty is in the bottom quartile. And the pattern continues as average teachers tend to move to average schools and bottom-quartile teachers tend to move to bottom-quartile schools. Case in point: Bottom-quartile schools disproportionately attract more bottom-quartile teachers (43 percent of transfers) compared to top-quartile schools (where 13 percent are bottom-quartile transfers). The net result of this movement of educators across schools? Differences in teacher quality are made worse.

We’re left with a mostly grim picture of how teachers choose to move around. Because even if we could finally figure out how to lure more effective teachers to the places that need them the most (more cash anyone?), there’s a strong possibility that once there, they could leave again if their new crop of colleagues aren’t up to their standards.

SOURCE: Li Feng and Tim Sass, “Teacher Quality and Teacher Mobility,” Education Finance and Policy (Summer 2017).

Spoiler Alert: If you’re looking for an objective review of this new paper from Chiefs for Change, you’re not going to get it from me. The idea advanced here—that content-rich, standards-aligned, and high-quality curricula may be the last, best, and truest arrow left in education reform’s quiver—is one that I’ve argued for years, and which E.D. Hirsch, Jr. has championed since shortly after the earth cooled. So what’s newsworthy here may be less what’s being said and more who’s saying it. Chiefs for Change is an organization comprised of district and state-level education leaders who collectively oversee schools systems attended by over 5 million kids in more than 10,000 schools. If some critical mass of those schools pursue the strategies recommend here, ensuring that “high-quality standards are matched with high-quality materials in a way that respects local control and supports strong student outcomes,” then a tipping point is near at hand.

Americans can always be counted upon to do the right thing, Churchill is said to have quipped, after exhausting all other options. That may explain curriculum’s emergence as a serious reform lever. But it is no accident that curriculum has been largely an afterthought in efforts to improve student outcomes. Our indifference is structural, baked into the K–12 pie. “Curriculum has often been considered a third rail in American education policy,” notes the report. Barriers to its serious consideration include “deep-rooted political controversy over how to teach subjects like social studies and science, and American norms that favor teacher autonomy and local control.” The paper does not elide these problems. Rather it explains how smart and skillful states and districts who see the value of quality curriculum have figured out how to pick their way through these minefields.

There’s a piece in the current issue of Education Next, which I authored, on the curriculum-based reforms undertaken in Louisiana under state superintendent John White and his talented deputy Rebecca Kockler. Many of the Chief’s “leadership lessons” are ripped straight that state’s playbook: “Use incentives, not mandates, to maintain local autonomy,” “leverage teacher expertise and teacher leaders in the work,” and “use the procurement process to expand use of the highest-quality curriculum,” for example. The report also helpfully restates the evidentiary case for curriculum, which while limited is tantalizing and persuasive. “Research suggests that, in the aggregate and for specific instructional programs, changing from ‘business-as-usual’ to a high-quality curriculum can boost student achievement,” the report notes. Perhaps most importantly, curriculum is also a largely cost-neutral reform. Bad textbooks and materials cost the same as good ones. What’s needed are curiosity sufficient to the task of separating good from bad, and policies that encourage more of the former and less of the latter. The emergence of independent curriculum reviewers like EdReports.org is a start, but these efforts “have largely revealed the relative lack of high-quality, [standards] aligned materials on the market. And even when information about quality and alignment is available, many state and district leaders lack the legal authority or the political will to incentivize the use of best-in-class curricula,” the paper reports. Just so.

State and district leaders now have this excellent roadmap to guide them in girding their loins to the fight for quality curriculum in their schools, which, in the end, shouldn’t be much of a fight at all. As the paper notes, the U.S. remains an outlier among high-performing countries, most of which have long prescribed a high-quality, content-rich curriculum. “Now, a group of states and districts are catching on and exerting leadership to develop strategies that make high-quality curricula and instruction much more likely in their classrooms.” Kudos to Chiefs for Change for adding its voice to the growing chorus of those urging more states and districts to follow their lead.

SOURCE: “Hiding in Plain Sight: Leveraging Curriculum to Improve Student Learning,” Chiefs for Change (August 2017).