Addressing high school dropout rates starting at the elementary school level

Improving education requires new voices, fresh ideas, and more questions

Can education reform get its mojo back?

A worthy requiem for Pat Moynihan

Addressing high school dropout rates starting at the elementary school level

The Education Gadfly Show: School choice for English language learners

Getting an A isn't easier if you're rich

Recent studies have examined the relationship between affluence and grade inflation in K–12 schools, concluding that grade inflation has been on the rise more in affluent schools than in schools serving less advantaged students. This finding has led to confusion, and both reporters and education policy wonks have misinterpreted it to say that grades are generally more inflated in the more affluent schools than in the less affluent ones. But this isn’t what the studies found.

Instead, these reports were referring to changes in grading over the past decade or two. The findings have confused journalists and the larger world of education policy because the term “grade inflation” is commonly used to refer to two related, but very different, phenomena.

The first meaning of “grade inflation” relates to the question of whether it’s generally too easy to get a good grade, something we might call “static grade inflation” or “the combined total amount of grade inflation in all of history.” “The students don’t understand even the basics of biology, yet they all got A’s and B’s—typical grade inflation,” you might hear from some disillusioned educator, shaking her head while referring to this type of grade inflation. Another example is a finding in Fordham’s recent report by Seth Gershenson, Grade Inflation in High Schools (2005–2016), that more than one-third of students receiving B’s in Algebra failed the state’s end-of-course exam for that course.

Yet the term “inflation” literally refers to changes that unfold over time. In this second meaning of the term, “grade inflation” basically means that grades are rising faster than other measures of learning. You could call this “dynamic grade inflation.” Using a variety of student data, researchers are able to answer a question such as “How much grade inflation has there been in the last fifteen years?,” and then go on to answer the question for different types of schools.

Both the aforementioned Fordham report and Michael Hurwitz’s and Jason Lee’s chapter in the book Measuring Success found that this latter type of grade inflation—the one about changes over time—was happening more in recent years in richer schools, and both studies made it explicit that their findings captured changes during the period on which the studies were conducted. The former reported that “during the years examined here, grade inflation occurred in schools attended by more affluent students but not in schools attended by less affluent ones,” and Hurwitz and Lee showed that “high schools enrolling students from more advantaged groups are inflating grades at a faster pace than are other high schools.”

Both found that, in recent years, it’s been getting easier for students in more affluent schools to get good grades, but neither study reported that it is generally easier to get a good grade in one type of school than in another.

Although these recent studies don’t answer the question of whether poor or rich students have it easier when it comes to getting a good grade, there is other evidence suggesting that it’s actually harder to get a good grade in an affluent school. For example, a 1994 study by the U.S. Department of Education (ED) found that students in high-poverty schools who got A’s had the same average English test scores as students receiving C’s and D’s in more affluent schools. For math, the A students in high-poverty schools had similar exam scores to the D students in the richer schools!

Since the recent reports have shown a faster pace for grade inflation in more affluent schools, might more affluent schools have closed the grade inflation gap since that ED report? After the Bluegrass Institute analyzed 2016 data from Kentucky on grades and ACT scores in response to Fordham’s report, I looked at the data they used and identified a similar pattern to that found in the ED’s earlier student-level study.

Kentucky shows virtually no gap in grades between these school types: the more affluent schools have an average GPA of 2.95, while the less affluent schools have an average of 2.93. Yet these equivalent grades almost certainly belie substantial gaps in achievement. Consider that more affluent schools have considerably higher ACT scores than the less affluent ones. Even comparing the forty more affluent Kentucky high schools with lower GPAs (i.e., below the state median) to the forty-one less affluent high schools with high GPAs (i.e., above the state median), the bad-grade/more-affluent schools have higher average ACT scores. Since Kentucky requires the ACT of all students, this is additional evidence that tougher grading is still coming from the more affluent schools.

Table 1: More affluent schools with low GPAs outperform less affluent schools with high GPAs on the ACT.

|

Cell values are average ACT Composite for each group of high schools |

Affluence |

||

|

More |

Less |

||

|

GPA |

Higher |

20.6 |

18.6 |

|

Lower |

19.7 |

18.7 |

Note: Cell values are mean ACT composite scores. Numbers of high schools for each group are: GPA Higher, Affluence More=43; GPA Higher, Affluence Less=41; GPA Lower, Affluence More=40; GPA Lower, Affluence Less=43. Socioeconomic status is indicated by whether the school is above or below the median percentage enrollment of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch in the state. Mean Composite ACT scores are weighted by school enrollment, but un-weighting them does not change the rank order of the average scores of the groups.

Grade inflation has been a concern for many decades, and there was probably never a time when getting a good grade was equally related to the mastery of knowledge and skills in all schools. This isn’t really so surprising, considering that grades are generally in the hands of individual teachers and schools rather than the district or state. So although these recent reports have added new evidence of the dangers of grade inflation—and the legitimately puzzling question of why it may be accelerating faster in more affluent schools—we still ought to view the findings about recent changes in the larger context. Sadly, schools serving disadvantaged students have often failed to hold their students to high standards or clearly communicate to them about their actual academic performance. A recent report from TNTP shows that poor and otherwise disadvantaged students are especially unlikely to get grade-appropriate assignments and teachers with high expectations for their learning.

The danger of grade inflation for disadvantaged students is not that colleges or employers will underestimate their academic performance because of their grades, as has been implied by coverage of these recent reports, but rather that, if everyone tells them they’re doing just fine when they actually are not, they won’t get the message until it’s too late.

Improving education requires new voices, fresh ideas, and more questions

In the hit tween book and movie Wonder (a kinder version of Mask), we learn the that main character’s teacher left Wall Street to pursue his dream of teaching. He challenges his students to think critically about what it means to be a good friend and a good citizen.

This story of overcoming obstacles in a world full of them is told beautifully — and it clarifies that education’s mission isn’t just the three Rs. It’s also about raising connected and compassionate leaders. In our child protagonist, we see a young person working to find the right fit in school. In his teacher, we see a talented career switcher in one of our most important professions, which itself is struggling mightily at the moment. In fact, according to the National Education Union, 80 percent of classroom teachers have seriously considered leaving the profession in the past year.

Dealing with the challenges of childhood that come with K-12 education is exhausting, but blame for challenges in the teaching profession cannot be placed at students’ feet. Today’s classroom is a polarized place. Even when change is necessary, it’s not easy. Questions of fit and environment are as important for our kids as they are for the adults who teach them. Though there may be disagreement about the right policy lever to optimize these two values, there should be no doubt that teachers, their students, and families across the country deserve better.

Perhaps the most essential question of the moment is, how do we ensure that education creates the opportunity for every child to develop his or her unique talents and abilities? We’re not close to the answer, especially when it comes to the neediest students in cities and counties hard hit by change. According to a survey by Gallup, the Thurgood Marshall College Foundation, and the Charles Koch Foundation, only 32 percent of people living in communities with low economic mobility across the country believe they have access to high-quality educational options.

Folks feel they’re stuck, and that’s because the national conversation is stuck, too. The United Negro College Fund’s “Done to Us, Not With Us” report concluded that the national conversation about education has been stagnant for some time and called for new voices.

At 50CAN, a network that supports local leaders working to improve education in their communities, we think you can’t imagine the future if you don’t talk about what it could be. So we’re trying to meet that challenge by supporting a National Voices fellowship program designed to amplify new perspectives and innovative ideas on how to improve learning for all students.

Fellows like Nicole Allen of SPARC, the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, are advocating for Open Educational Resources — a way to bring free, high-quality, and flexible educational materials to students, especially in communities in need, by breaking down regulatory, legal, financial, and technical barriers. One initiative she promotes is the technology platform and publisher OpenStax at Rice University, where millions of students have access to free, high-quality, peer-reviewed textbooks, saving them more than $177 million this year alone.

Evy Jackson, a former Colorado gubernatorial education aid and charter school board member, has worked for five years to improve access to quality public schools — changing key elements of the state’s school finance system and supporting families of color as they advocate for greater personalization and change. She, too, brings enormous experience, will, and, most important, openness to the discussion about improving education.

The first class of National Voices fellows comprises 10 rising education leaders from across the country, providing a unique opportunity to collaborate, connect, and debate with a diverse and passionate mix of voices over the next year.

There’s no identifiable ideological strain among 50CAN’s fellows because there’s no canned pedigree. The only requirements are that fellows resist the polarization of the moment, believe that families, teachers, and students have a voice in what works best, and commit to rethinking what education can mean. They have to be willing to imagine what today we cannot even fathom. As a result, libertarians and leftists, union members and reform advocates are coming together at the local level to discuss policies that will improve student well-being and allow children to develop their unique aptitude and become critical thinkers and lifelong learners.

In Wonder, the courageous teacher outlines a new precept for his students each month. February’s direction is from the American humorist James Thurber: “It is better to know some of the questions than all of the answers.”

When it comes to how to best educate children, we don’t know all of the answers, but we should commit to empowering new voices, fostering innovative ideas, and asking lots of questions.

Derrell Bradford is executive vice president of 50CAN and a visiting senior fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Brennan Brown is the director of educational partnerships at Charles Koch Foundation.

This essay was originally published by The 74 Million.

Can education reform get its mojo back?

I recently returned from the Policy Innovators in Education (PIE) Network Summit in New Orleans. PIE occupies a unique space within the education reform community, bringing together policymakers and advocates to explore common ground—embracing a range of ideological and partisan differences in pursuit of educational equity and excellence. I always look forward to its eclectic mix of ideas, participants, and speakers. This year’s event featured Louisiana State Superintendent John White.

There are few public officials today as respected and admired as White is within education reform circles. I first met him in Indianapolis in 2012, shortly before he was tapped for his current role, which feels like a lifetime ago in education reform years. White has lasted far longer than most of his contemporaries; his time in office has been instructive because education often doesn’t deliver the instant results that politics demands.

White’s remarks in New Orleans offered a reflection on his tenure as well as a renewed challenge: how to keep the country focused on improving education for all students and keep the ed reform policy discussion fresh and relevant. The question of relevance is not trivial, given today’s hyperpolarized environment and the tribal identities that are increasingly shaping our debates. The reluctance of politicians to substantively engage on education is surely tied to the bruising battles that have been waged, as well as the many distractions that have made it more difficult to keep education reform in the spotlight.

The flight of politicians—as evidenced by the upcoming gubernatorial elections—from our issue isn’t the only cause for concern. A huge question we have before us is how to talk about the importance of shifting our policy priorities while also holding onto the reforms that have led to success over the last decade. In the meantime, education reform’s orphaned status—what White decries as consignment to a back-page issue—is music to the ears of those eager to write education reform’s epitaph.

When I was in Indiana, at a time of far greater bipartisan alignment on education issues, a Democratic controlled federal government stood shoulder-to-shoulder with our GOP-led state education agency on reforms regarding teacher quality, school turnaround, and charter schools—which we valued—but they were noticeably absent when it came to our efforts on collective bargaining and school vouchers. Some might recall that we took a hard line when the feds resisted our Race to the Top application. Internally, we had a few choice words for our friends in Washington, D.C., but any differences paled in comparison to the shared aims that allowed us to keep our arms locked.

Fast forward to today, and White is exactly right when he laments that politicians—if they attend at all to education—are often only interested in “thin solutions.” In White’s estimation, these tend to deal specifically with either postsecondary education or early childhood. The policy real estate in the middle—where grand education bargains have previously been forged—is rapidly shrinking. Moreover, there’s hardly much incentive to stay in the middle for fear of being squashed like a grape. It’s an unfortunate dynamic that undermines the compromise and coalition-building necessary to help solve education’s long-standing problems.

White argues that today’s divided politics have made education reform a far less attractive issue—especially to the next generation of policymakers and advocates— because there are no easy fixes. Something has to change, but I’m not sure—as White posits—that the answer lies in new ideas. As we learned from the last wave of reforms, they are too quickly discarded as tired and ineffective. There’s also the tendency to get distracted by ideas that divide us rather than those that might unite us. Of the few areas that enjoy greater bipartisan accord (e.g., career and technical education), it’s unclear whether they hold the most potential for all of us reformers—left, right, and center—to rally around or if they can lead to meaningful systemic improvement.

No, if anything, the answer has more to do with educating parents, media, and community members about the need to continue building upon the success we have had. Hard issues like literacy or the achievement gap—important topics that previously energized our movement—have yet to be solved, but have yielded valuable lessons. Sadly, that has never been an exciting space for politicians running for office. Yet, it is the very reason organizations like the PIE Network exist. My hope is that policymakers and advocates shoulder additional responsibility in re-elevating ed reform’s primacy, but they must also be willing to put their differences aside to do so.

It’s a hard ask, especially with the leadership vacuum that has led to the collapse of the bipartisan education reform agenda. And it’s been unnerving to watch advocates split hairs with (or pounce upon) one another rather than using this energy in more productive ways. Yet in spite of this noise, all of the conversations I had in New Orleans have me convinced that our community is far less splintered than popularly believed. Reform can get its mojo back, but it won’t be easy. The first step is remembering when and why each of us decided to dedicate our lives to this issue, and rediscovering our shared commitment to vanquishing educational mediocrity.

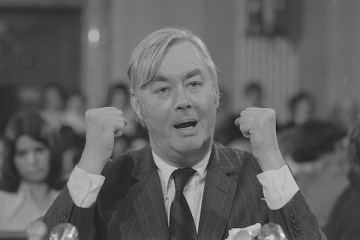

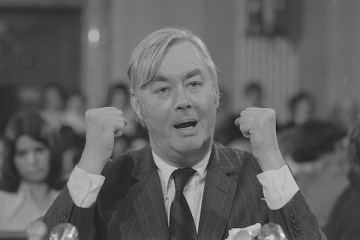

A worthy requiem for Pat Moynihan

Tragically, the mold seems to have been irrevocably shattered, if not discarded on the ash heap of history. Surrounded by the politics and politicians that plague us today, and the wretched campus climate that we’re living with, to view the great new documentary about the late Pat Moynihan is to weep over what’s practically vanished from American public and intellectual life: independent thinkers, policymakers both intrepid and persistent, respect for data, reverence for the truth, determination to stand up for what’s best about America while acknowledging its failings, and a willingness to cross the lines of party and ideology in pursuit of better outcomes for people who need them.

Yes, you can find a few aging practitioners still treading carefully on Capital Hill, but you won’t find any who also convey Moynihan’s erudition, bravura, persistence, humor, and charm, let alone his depth of knowledge and capacity to create more of it. (After Pat’s death in 2003, George Will—who figures prominently in the new documentary film about his life—wrote that “His was the most penetrating political intellect to come from New York since Alexander Hamilton.” Will also quipped that Pat “wrote more books than some of his [Senate] colleagues ever read.”) You certainly won’t find many in academe who combine his intellect, his rigor, his courage, and his respect for data. Recall the much-quoted Moynihan one-liner, today so often honored in the breach, that everyone is entitled to his own opinion but not to his own facts.

This terrific documentary—a biopic, nearly two hours in length, from independent filmmaker Joe Dorman—recounts the many chapters in Pat’s life, from growing up in hard times, through the much-debated “Moynihan report,” to his service under four presidents, his four terms in the U.S. Senate, his writings, his controversies, his family and friends, admirers and detractors, and so much more. You are apt to be surprised by how varied those chapters were—and how remarkably diverse the cast of commenters who evoke them in this documentary.

I was profoundly fortunate to have Pat Moynihan as a mentor. Indeed, for fifteen formative years of my life (roughly 1966 to 1981) I mostly labored in his shadow (Nixon White House, U.S. Embassy in Delhi, U.S. Senate), learned so very much, and perhaps contributed a bit. Many others were also shaped by him. (It’s an awesome alumni/ae club!) But so—more importantly—was the country in which we live.

The film—simply titled Moynihan—has already premiered in New York and Los Angeles. It apparently opens this weekend in the D.C. area at the AFI theater in Silver Spring, Maryland, though it’s still a little murky as to when exactly it will be shown. Do your best to see it whenever/wherever you can. Then raise a glass—definitely the apt tribute—to Pat’s memory, shed a tear for what’s all but vanished from the contemporary scene and, if you can, imagine what would be needed for even a semblance of this mold to be recreated in today’s America.

Addressing high school dropout rates starting at the elementary school level

The City Connects program is an initiative of Boston College that works to address non-cognitive barriers to student success among elementary school pupils in Boston Public Schools (BPS), as well as charter and private school students in Boston and other nearby cities. It was piloted in six low-performing BPS elementary schools in 2001, assessing needs and providing access to services for students via a third party rather than through the schools themselves.

Those services can include academic tutoring, social-emotional development, health needs, and family supports. Full-time coordinators are embedded in the schools and monitor need, referrals, and successful use of these services, obviating the need for teachers to become de facto social workers and for school administrators to become service providers. A fuller description of the program can be found here. It is important to note, for purposes of this study, that City Connects is limited to elementary school.

Because of its genesis within Boston College’s Lynch School of Education, City Connects has been widely studied by the school’s researchers. The latest report looks at long-term effects of the program on combatting high school dropout. The students under study were part of the first five cohorts of kindergarteners and first-graders to participate in the pilot program, from the school years 2000–01 through 2004–05. A team of researchers led by Terrance Lee-St. John followed the enrollment histories of those youngsters throughout their schooling in BPS through the 2013–14 school year, when the youngest of the students were in ninth grade and the oldest had just graduated high school. The comparison group comprised students in the same school-year cohorts who attended BPS schools not participating in City Connects. Students were excluded from both groups if they received high school instruction in “substantially separate” special education placement, if they permanently transferred out of BPS prior to reaching ninth grade, or did not reach ninth grade by 2013–14 due to being held back in prior years. The final sample studied included 894 City Connects students and 10,200 non-City Connects students.

Because of the small number of school buildings involved in the pilot initially, all treatment effects were calculated at the student level. Overall, treatment students registered a 9.2 percent dropout rate in high school, compared to 16.6 percent for the non-treatment students, a fairly wide variance that points to significant positive effects, especially for an intervention that happened years prior. The most significant benefits showed up for black students, those who qualified for free- or reduced-price lunch, and males. Interestingly, BPS provides withdrawal codes indicating the reasons—as far as they are known—for students dropping out. While more treatment students than non-treatment students dropped out due to incarceration and for unexplained reasons, more treatment students also dropped out to take up employment or due to GED completion than did their non-treatment peers.

Caveats offered by Lee-St. John and his team are worth noting. Selection effects could threaten the validity of the study if, for example, more conscientious and involved families enrolled in the treatment schools, which could drive a spurious correlation between the program and student outcomes. Since researchers cannot control for the families’ conscientiousness, we should take these large effect sizes with the caveat that selection bias could be driving some of the findings. Additionally, the observable demographic makeup of students in the treatment and non-treatment schools is somewhat different, although the researchers describe efforts to control for those differences.

How does an elementary-level intervention help reduce the likelihood of dropouts by nearly fifty percent years after treatment has stopped? Part of the reason could be that students are connected with service providers independent of their elementary schools. It is possible that service provision along many lines continued throughout middle and high school, but the researchers do not test that possibility, noting only that the effects of treatment are significant over time. City Connects touts its multi-faceted and student-centric support structure as addressing multiple barriers to student success. This and other research from Boston College seem to point to its effectiveness, but the aforementioned caveats give rise to some skepticism, and more data would help confirm these effects and pinpoint the source.

SOURCE: Terrance J. Lee-St. John et. al., “The Long-Term Impact of Systemic Student Support in Elementary School: Reducing High School Dropout,” AERA Open (October 2018).

The Education Gadfly Show: School choice for English language learners

On this week's podcast, Madeline Mavrogordato, an associate professor at Michigan State University, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss the relationship between English language learners and school choice. On the Research Minute, Adam Tyner examines how New Orleans’s choice-based system affects students’ commute times.

Amber’s Research Minute

Jane Arnold Lincove and Jon Valant, “New Orleans Students’ Commute Times by Car, Public Transit, and School Bus,” Urban Institute (September 2018).