Career pathways in the First State

By Paul Herdman

In the last decade, Delaware’s once very stable economy felt some seismic shifts. The General Motors and Chrysler plants closed, causing the loss of thousands of blue-collar jobs. Dupont, a major employer in Delaware for centuries, was going through a massive merger with Dow Chemical. Couple these shifts with sweeping digital transformations in the banking industry, another staple of our economy, and it was clear: Our once robust economy was now fragile. On top of which, our K–12 system was largely evolving in its own silo, unconnected with these shifts in Delaware’s “real world.” There was a growing gap between what our economy needed and what our kids were able to do.

Fast forward to 2018. All across our small state, young people’s vision of the future is becoming a lot clearer. They’re exploring their passions and matching them to potential careers with the help of a network of expert adults. They have far crisper answers to the “what do you want to be when you grow up?” question. And they’re learning more and more each day just what steps they need to take to reach their dreams.

In a few short years, Delaware Pathways has begun to transform the education landscape here. Delaware aims to enroll 20,000 students in career pathways by 2020. That would be about half of our high school students. The public and private sector leaders engaged in this work feel good about our collective chances of reaching that goal.

If we’re successful, this would not just be an interesting addition to the existing system; it could fundamentally redesign it.

I’ll come back to these future possibilities, but first let me explain what Delaware Pathways looks like today and why it’s grown so fast.

Pathways Basics. Pathways expands on the runway that our vo-tech schools built to help a broader range of students, especially traditionally underserved students, gain the knowledge and skills needed in Delaware’s high-demand occupations. But because the economic landscape is changing so fast, and because the talent gaps are so large, this work has evolved and expanded to almost all of our comprehensive school districts and charter high schools. So this is not just for students in our vocational schools, this is now for all students, including those in a traditional “college prep” path.

Career pathways match students’ interests with tailored instruction and relevant work-based learning experiences, and award industry-recognized credentials and college credits while students are still in high school. The program connects the K–12 system to higher education, local employers, and community partners, and it does so with particular emphasis on growing industries like finance, health care, information technology, and advanced manufacturing.

From the first pathway of twenty-seven students in advanced manufacturing in 2014, there are now fourteen pathways serving over 9,000 students in the fields mentioned above, along with many more, like computer science and teaching.

A unique feature of Delaware’s approach to this work is that our statewide work-based learning intermediary is our one community college system, Delaware Technical Community College. They were a natural choice in that DTCC has campuses in each of our three counties and they already partner with many of our schools on dual enrollment and with many of our employers on job training. Another feature of Delaware’s public policy environment that strengthens our pathways work is that the state has two scholarship programs that provide students who leave high school with a GPA of 2.5 or better with two years of free or significantly reduced tuition at Delaware Tech, Delaware State University, or the University of Delaware’s Associate in Arts program.

The value proposition. Pathways grew fast in Delaware because of the point I made earlier: The value proposition made sense, and we were facing a crisis. For decades, we’ve seen initiatives that made sense to “reformers” and the private sector, but not so much to practitioners. And other ideas that seemed to resonate with those in the trenches didn’t with those who held the resources and political power to make them happen at scale. But this career pathways idea resonates with a large swath of folks both inside and outside our schools.

Moreover, this will help all students identify the education and career options in their field of study, including those on the traditional “college track.” Upwards of 65 percent of the jobs in Delaware are going to require some level of education beyond high school. Some young people will earn industry-recognized credentials and be prepared to enter their profession right out of high school. Others will continue their education through certification programs, associate or bachelor’s degrees, or more.

These pathways are meant to provide on and off ramps for the full spectrum of options. A young person on a healthcare pathway could use it to decide: a) to become a certified nursing assistant so she can start earning some money while she weighs her options; b) to start working towards becoming a medical doctor; or c) that it isn’t the right field. All are good choices. Parents and students are savvy, they know the cost of college, and they know that the workplace is less forgiving, so we’re already hearing that this value proposition resonates. Whatever field a young person wants to pursue, getting a feel for what that work might entail and building up people-skills while still in high school just makes sense.

The Drivers. Good ideas are often borne of necessity. In Delaware, three vectors—business, home, and school—aligned to create a perfect storm.

To my earlier point, our private sector and political leaders saw major shifts occurring in our economy. Though Delaware still boasts a triple-A bond rating and once had more Ph.D.s per capita than any state in the nation, the big changes underway simultaneously in both our blue- and white-collar sectors were a major cause for concern. Like much of the country, we were being hit with the one-two punch of automation and globalization.

There was a clear mismatch between the changing economy and the skills that our students were developing in high school. Employers were increasingly seeking to hire candidates with not only technical skills, but also strong soft skills like communication, problem solving, and teamwork. Thousands of jobs across the state were available yet out of reach for many Delawareans.

Our schools felt it, too. Despite our efforts to move the academic needle via some serious (and, in my view, very helpful) infrastructure funding from Race to the Top ($119 million) and the Early Learning Challenge Grant ($49 million), our NAEP results have been disappointing. These federal investments did help us build consistently high academic standards, stronger teacher and leader pipelines, much better early-learning infrastructure, and one of the best data systems in the country. But these improvements were being swamped by economic reality. As the number of low-income students rose to nearly 40 percent of the population, new data showed that more than 40 percent of our high school graduates were not ready to take credit-bearing coursework at local colleges. And employers said that too many of their new hires weren’t ready to succeed without considerable additional training.

Though we saw some positive trends relative to a number of other states, our low-income, African American, and Hispanic students and those with disabilities were graduating at far lower rates, were less likely to enroll in college, and more likely to need remedial coursework if they did attend. Given that our children of color were the new majority, it was clear: The existing high school model was not working for everyone and was failing some groups of young people at disproportionally high rates. At least as telling: Students often stated that what they were learning in school just wasn’t relevant.

In short, we had a crisis on multiple fronts. Our economic infrastructure was more fragile than it had been in decades—and it was starved for the talent needed to rebound. And our K–12 leaders knew they needed to rethink what school looked like—high school especially—and how they were partnering with higher education, parents, and employers.

Building Momentum. By the time Delaware Pathways started to emerge in 2014, it was like water hitting a parched garden. Former Governor Jack Markell connected with Bob Schwartz of Harvard and learned about a new initiative called Pathways to Prosperity. After a public discussion on the topic at the University of Delaware, our business leaders, including a group called the Delaware Business Roundtable Education Committee (DBREC) and Rodel, worked with the state to enroll in the Pathways Network. In parallel, our largest high school, William Penn, was partnering with Delaware Technical Community College to build a new “advanced manufacturing” pathway to develop students who could support the state’s manufacturing workforce, including leading-edge companies like Bloom Energy, which was interested in expanding to Delaware and needed a highly skilled workforce to help them design fuel cells.

The momentum built quickly. Key to that growth was leadership, people, and a plan. Governor Markell started the race, and current governor John Carney has taken the baton and is running with it. Having state leaders signal to the public and private sectors that this is important has been crucial. And Delaware being a small state also helped. We all talk to one another—and the people implementing the work are critical. Some important leaders in our Department of Education, Department of Labor, and Workforce Development Board started meeting regularly with the governor’s office, along with some key nonprofit and business leaders. This cross-sector collaboration was held together with a strong strategic plan. (A case study by Jobs for the Future and Harvard gives more detail about Delaware’s efforts.) The plan is clear, bold, and simple. It lays out roles and responsibilities, and the working team uses it as a framework for not only quarterly “stock takes,” but as a way to maximize every dollar we bring in through a braided public and private sector funding strategy.

Taking Stock. Today, all of our nineteen school districts offer at least one career pathway option. For students and their families, the benefits are clear: Young people begin exploring realistic and in-demand careers, but they’re able to do this pressure-free, while they’re teenagers, then sharpen their focus as they progress through high school and into postsecondary education. Job shadowing and work-based learning give them a personal look into what their future holds. And if they don’t like what they see, they can change the picture before embarking on college. These experiences help students gain essential employability skills, including teamwork, communications, and perseverance. And opportunities for dual enrollment and industry credentials are major time and money savers.

As for the state’s political and business leaders, they’re excited that the solution to new economic challenges could be right under their noses. The prospect of a well-prepared, pre-trained army of budding professionals in their own backyard is a big motivator. As a result, many of our top employers—from storied Dupont to emerging tech firms—are working hand-in-hand with K–12 schools, our community college system, and others to invest in Delaware’s future workforce.

The Path Ahead. We still have a lot to do, as we’re not even halfway to our goal of 20,000 students by 2020. But we are on a good path. Delaware Tech, our statewide “intermediary,” is building out a new office of work-based learning to connect the dots among employers and students. And our state leaders have been smart and adept in leveraging federal, state, and private sector partnerships with JPMorgan Chase and Bloomberg Philanthropies, as well as at least fifteen of Delaware’s own major employers.

***

As Jon Schnur of America Achieves recently pointed out at Delaware’s annual Pathways Conference, “Our world is changing faster than at any time in its history, arguably faster than the Industrial Revolution. The implications of not adequately responding to these shifts is that it has the potential to destabilize our democracy.”

This is not just an interesting initiative, and not just something for Delaware. It’s pivotal to our nation’s future. If we can work collectively to create real and lasting linkages to bridge the gaps between high school, higher education, and work, we have an opportunity to rethink, and to continue adapting, what public education needs to look like to give our kids a chance to thrive in a world we can’t yet see.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Editor’s note: Last week, at the University of Southern California, the annual Education Writers Association conference kicked off with a speech by USC professor Shaun Harper on “Big Ideas on Equity, Race, and Inclusion in Education.” That was followed by a panel on the same topic featuring Dr. Harper, Estela Bensimon, Pedro Noguera, and the Fordham Institute’s Michael J. Petrilli, moderated by Inside Higher Ed’s Greg Toppo. These were Petrilli’s comments as prepared.

Shaun's comments were well said, though you won't be surprised to know that I disagree with many of his arguments. I'm happy to get into that, as Greg sees fit.

But first I want to focus my comments on you, the reporters.

We all know that this is a difficult time to talk about issues of race and class in this country, thanks to the extreme polarization and division, including on this issue. Of course, President Trump doesn't make it any easier, as he shows no interest in bringing us together or bridging divides. In fact, he seems intent on making the divides even larger, with his awful race-mongering at his rallies and in social media, and with many of the actions his administration is taking. This is why I was a Never Trumper, and why I left the Republican Party after Charlottesville.

But the rest of us shouldn't play his game. And especially when discussing these highly fraught issues around race, we should work extra hard to find common ground, and find solutions.

It's my belief that the overwhelming majority of Americans, and the overwhelming majority of educators, are sympathetic to the concerns Shaun discussed. It disturbs us that so many kids of color continue to face unfair barriers in their educations and in their lives, and we want to do something about it.

But we can't have productive conversations if those conversations are quickly shut down. And that's what I see too often: conversations on race shut down if those of us on the right express disagreement with the views of folks on the left. If we say, for example, that we agree that racism and racial bias are real, and are factors in the gaps and disparities we see, but we don't think they are the only factor, that other factors matter, too, including families, and personal responsibility, and student behavior—if we say these things that are perfectly reasonable, too many times we are called racists. We are thrown in with the neo-Nazis in Charlottesville.

And reporters are sometimes complicit. I see this in the debate around discipline disparities. We are all alarmed by the fact that African American students are three times as likely to be suspended as their white peers. We are open to finding solutions to that problem.

But in the press we are caricatured. Civil rights groups and other progressives think the disparities are being driven by racism and racial bias. The conservative view is not that racism or racial bias aren't factors, or don't exist. Anyone who has studied American history, slavery, Jim Crow, understands the racist history of this country. And anyone who understands human nature and cognition knows that implicit bias is a real thing, and something we all have to be on guard against in our own lives. Of course racism and racial bias are part of the story.

The conservative position, though, is that it's not the entire story. When you go and look at the best evidence—the most rigorous studies and surveys of students themselves—it is undeniable that the other big part of the story is student behavior. Some groups of students misbehave in school more frequently than others: African Americans more than white students, white students more than Asian American students, and so forth. This is not because of their race, but almost surely because of various risk factors that are connected to student misbehavior, all of them related to poverty.

African American kids are three times as likely as white students to grow up in poverty, even more likely to grow up in deep poverty, three times more likely to grow up without a dad in the home, much more likely to be exposed to lead poisoning, more likely to be in the child welfare system, and on and on and on. This is a tragic state of affairs, and much of it is the legacy of racism. But we can't wish it away.

And it matters for discipline policy because, if you expect to reach perfect parity in suspensions, but student behavior varies, you are telling educators to stop holding certain kids to high expectations. And that's not good for the kids, and it's certainly not good for their peers, or for a positive school climate. And it also paints educators as the problem, when the truth is much more complicated.

And yet when I've argued that student behavior is part of the issue, that it varies by race, not because of race, but because of these other factors, people in this room have called me a racist. Can we stop doing that?

So again, to the reporters, my plea is this: On issues of race, but really all issues, please check your own biases, including ideological and political biases. When your editors tell you to include the conservative point of view, please work hard to really understand it. Don't caricature it. Don't make it sound like conservatives are denying racism and racial bias in the same way some deny climate change. These issues are complicated and complex—and your readers deserve to see them portrayed that way.

Comparing Ohio K–12 education to other states helps us gauge the pace of progress, provides ideas on improvement, and gets us out of our local “bubble.” In a recent post, my colleague Chad Aldis examined Ohio and Florida’s NAEP results, finding the Buckeye State wanting in terms of gains over the past decade. Terry Ryan has also offered an insightful comparison of Ohio’s charter policies to Idaho’s. This piece follows a similar path and takes a look at Ohio’s charter landscape relative to Arizona’s.

Why the Grand Canyon State? For starters, Arizona has a significant charter enrollment of about 180,000 students, or 16 percent of public-school enrollment (Ohio has roughly 110,000, or 7 percent). Arizona charters are also producing some stellar results. As Matthew Ladner has repeatedly (and I mean repeatedly) shown, Arizona charters have posted high scores on NAEP—and for two years straight, US News & World Report placed several of them in its top-ten high schools in nation.

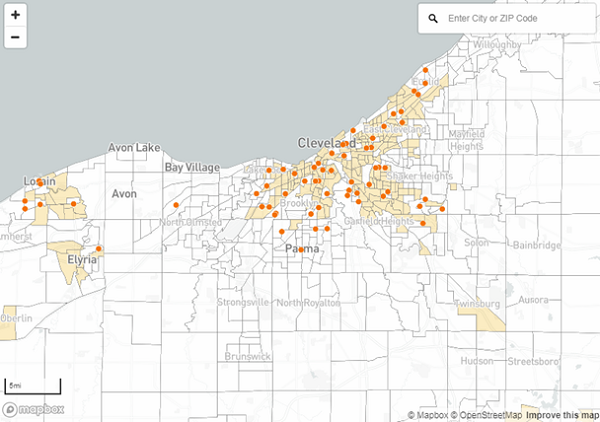

Let’s start by comparing a couple terrific maps that my Fordham colleagues produced in their recent Charter School Deserts report. Figure 1 displays the charter locations for the Cleveland metro area. What you’ll notice is that the vast majority of charters—the orange dots—are located within the city limits and largely in high-poverty neighborhoods (areas shaded in pink). Yet charters are noticeably absent from outlying high-poverty communities, such as Willoughby, Mayfield Heights, Solon, Strongsville, and Avon Lake.

Figure 1: Locations of charter schools in the Cleveland area

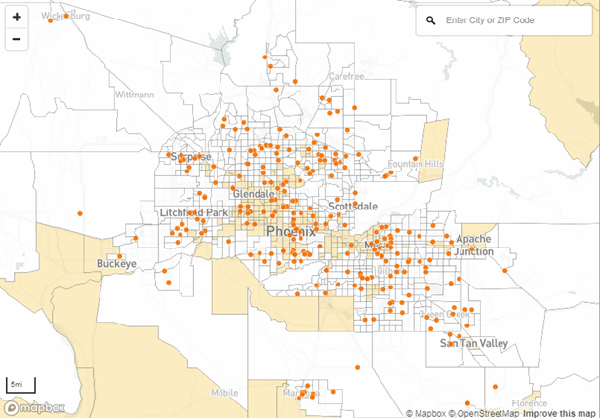

Now let’s look at Phoenix. This figure shows a remarkably wide geographic distribution of charters—literally all over the map. They’re located in high-poverty, inner-city neighborhoods, as well as more affluent suburbs, like Litchfield Park, Surprise, Scottsdale, Gilbert, and Queen Creek. You could live almost anywhere in metro Phoenix and not be more than fifteen minutes from a charter school. That’s not the case if you happen to live in a Cleveland suburb.

Figure 2: Locations of charter schools in the Phoenix area

These maps reflect very different policy approaches to charter-school formation. On the one hand, Arizona (and almost every other state) places no geographic limits on charter development, while Ohio places strict restrictions. Under Ohio law, startup charters are only allowed to open in “challenged” school districts, including those in Lucas County, the Big Eight, and other “low performing” districts, as defined in statute.[1] Today, startup charters are limited to just thirty-nine out of Ohio’s 610 districts. This explains the absence of charters in suburban Cleveland and almost anywhere else outside of Ohio’s urban core (see the full state map here).

Putting a geographic lid on charter formation does have some upsides. It has focused school developers’ attention on Ohio’s highest-poverty areas—locales where the educational needs are the greatest. Today, the Buckeye State is blessed with some terrific urban charters that are significantly improving students’ lives. It also avoids the political rancor that would likely follow a removal of suburban districts’ “territorial exclusive franchise” over public education, as Ted Kolderie once put it.

But with stronger charter accountability laws now in place, Ohio lawmakers should work to remove these geographic restrictions. Here’s why.

Suburban families are searching for different public school options. Although polls indicate that a majority of parents give their local public schools solid marks, about 40 percent are less satisfied, and a similar proportion think that more options would be beneficial. If Arizona is a bellwether for actual demand, a fair number of suburban parents are indeed seeking different schools for their children. For example, the Great Hearts charter network offers a distinctive classical liberal arts curriculum; today it has twenty-three schools across metro Phoenix and waitlists of some 20,000 students. Also in the Phoenix area are BASIS charters, which recently dominated the US News’s top-ten rankings. They’re proving to be a solid option for middle-class families seeking rigorous academics. It’s not just Arizona either. Recently, Wired magazine wrote on Design Tech High School in Silicon Valley, a charter school that, in close partnership with Oracle, focuses on technology, design, and entrepreneurship. Even in Ohio, some suburban families are trekking to quality charters like Columbus Preparatory Academy and Arts and College Preparatory Academy located just within big-city district limits. And as Charter Deserts so starkly reveals, many suburban families in Ohio are low-income households whose children are most in need of quality school options.

Charters in booming suburbs would provide options for families seeking smaller learning environments, especially in high school. I graduated from a mid-sized high school with a class of about 300 students. At times, I felt lost in a school of that size. But there are larger high schools than even that: In last fall’s enrollment counts, forty-two Ohio high schools reported senior classes of at least 400 students—many located in suburbs like Mason, Lakota, Kettering, and Olentangy. As these communities continue to grow and fill sprawling comprehensive high schools, some students may find it difficult to develop close relationships with teachers or classmates. Indeed, that may already be happening, as recent survey data found that public-school teenagers report weaker connections with adults working in their schools. Though many families and students will prefer large-school environments for a variety of reasons, others might want the smaller settings that charters often offer.

Charters in rural and small towns can foster close-knit communities of support. Thus far, we’ve concentrated on suburban locales, but the charter model can also provide opportunities for families in rural and small towns. Consider Ellen Belcher’s eye-opening profile of Sciotoville Elementary Academy that illustrates how one charter school in rural Appalachia goes the extra mile to serve its families and students. Other rural residents around the nation (including—you guessed it—Arizona) have used the charter model to maintain a cohesive community. Due to modest populations, small town and rural charters may never gain economies of scale, necessitating more creative ways to organize learning. But all communities, even smaller ones, should have the ability to form public schools that meet their local needs.

Allowing new charter school formation throughout Ohio would broaden support. National polling suggests that most people know little to nothing about charter schools. With almost no presence across massive tracts of Ohio, odds are that most Buckeye families know little about charters (alas, save perhaps for ECOT). This means Ohio charters have a narrow base of support, limited to those who have been well served by them and people who generally agree with the concept of school choice. To build a broader, stronger base of support, the next generation of Ohio charters will likely need to serve families and students from a wider range of communities.

* * *

The lesson from the Arizona is that families of all backgrounds and walks of life can benefit from charter schooling done well. Of course, simply removing Ohio’s geographic cap is no guarantee that charters will actually open in untouched parts of the state; it’ll take a supply-side response from educational and community leaders willing to start schools, as well as parents who enroll their children in them. But removing this legal barrier to entry is a necessary first step for charters to grow throughout all areas of Ohio.

[1] Districts themselves or regional Educational Service Centers may open a “conversion” charter school in non-challenged districts. In 2017–18, just 14 percent of Ohio charters are conversions.

On this week's podcast, Kimberlee Sia, CEO of KIPP Colorado, joins Alyssa Schwenk and Brandon Wright to discuss charter school deserts in the Centennial State. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines the effects of low-cost efforts to mitigate chronic absenteeism.

Todd Rogers and Avi Feller, “Reducing Student Absences at Scale by Targeting Parents’ Misbeliefs,” Nature Human Behaviour (April 2018).

Back at the turn of the millennium, we at Fordham published a paper that urged a stronger focus on phonics. Author Louisa Cook Moates wrote: “Reading science is clear: young children need instruction in systematic, synthetic phonics in which they are taught sound-symbol correspondences singly, directly, and explicitly.” The reading wars—the longstanding debate between “whole language” and phonics proponents—has been mostly settled in the U.S. with phonics playing a key role in the federal Reading First program, and having now been embedded in most states’ English language arts standards, including Ohio’s.

Recently, British policymakers also took bold steps to prioritize phonics, i.e., structured instruction that teaches children to “decode” words. Coinciding with an influential 2006 paper known as the “Rose Report,” which recommended phonics as the principal strategy for early literacy, England began requiring its schools to move away from the nation’s “searchlights” model and instead implement phonics-centered instruction for children aged five to seven.

A recent study by Stephen Machin, Sandra McNally, and Martina Viarengo evaluates the impact of this initiative, which also included government aid allowing schools to hire literacy consultants who supported teachers’ transition to phonics. The policy was implemented in waves with eighteen local authorities participating in the pilot phase in 2005–06 and another thirty-two in the first full phase in the next year. By 2009–10, all local authorities had adopted the phonics-based program. The researchers use quasi-experimental methods to compare the test results at ages five, seven, and eleven of students who attended schools in the pilot and first phase (the “treated” group) to those unaffected by the first two waves of implementation.

Their analyses find that students benefitted from the shift towards phonics instruction. At age five, children in both the pilot and first phase posted substantial gains on reading tests of about 0.22 to 0.30 standard deviations—what the researchers call an “instant effect” of the program. The study also uncovered positive results at age seven of roughly 0.08 standard deviations. However, by age eleven, the effects were essentially zero, leading the researchers to speculate: “Most students learn to read eventually. This is the simplest explanation for why we do not see any overall effect of the intervention by age 11.” Nevertheless, though the effects for students on the whole may have dissipated, the benefits were larger and more persistent for low-income pupils and non-native English speakers. For instance, at age eleven, children from both of these groups demonstrated gains of approximately 0.05 to 0.07 standard deviations (some findings were statistically significant, but others were not). This leads Machin, McNally, and Viarengo to conclude: “Without a doubt the effect [on less advantaged students] is high enough to justify the fixed cost of a year’s intensive training support to teachers.”

Based on studies showing that reading proficiency by third grade predicts better outcomes later in life, policymakers in Ohio and other states are focusing much attention on early literacy initiatives. Can a continuing emphasis on phonics instruction prove beneficial, especially for children most apt to struggle in reading? The evidence from England—along with studies from this side of the pond—indicates that the answer is yes.

Source: Stephen Machin, Sandra McNally, and Martina Viarengo, “Changing How Literacy Is Taught: Evidence on Synthetic Phonics,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (2018); open version is available here.