One of the biggest shifts in recent years—within the education policy community, but also the larger culture—has been a gradual move away from the “college for all” mantra. And it’s not just in the ephemera of mindsets and beliefs. Hard numbers show a marked decline in the proportion of high school students matriculating directly to college. As the Wall Street Journal reported in May, “More high-school graduates are being diverted from college campuses by brighter prospects for blue-collar jobs in a historically strong labor market for less-educated workers.”

Far from something to deplore, this trend is a positive development—but only so long as the right teenagers are choosing to enter the labor market rather than pursue college. No, “right” isn’t coded language for race or class. I have in mind individual students, and the question of whether they are likely to succeed in—and complete—postsecondary education. That’s a critical question because we know that higher education usually pays off—but only for students that exit college with degrees or other valuable credentials.

If Jack is good at school, with decent grades and pretty good test scores, and he’s got the motivation to keep at it, going to college is a solid bet. But Jill, who struggles in school, with mediocre or worse grades and below-average test scores, is a tougher case. With the right support, she might turn out to be a late bloomer and could succeed in higher education. But more likely, she will give it a try and then struggle, just as she did in high school, then drop out with nothing but debt and regret. She would have been better off taking a full-time job, and using that to grow her skill set. (It would have been even better had Jill had the chance to do high-quality career and technical education while still in high school, to give her momentum toward a valuable career.)

It would be great to know, then, whether the national decline in college-going represents a lot of Jacks or a lot of Jills. Sadly, I’m not aware of any study that’s looked at that question. What we can do, though, is glimpse at the aggregate and put the college-going rates in context. Specifically: How do these rates compare to college readiness and college-completion rates?

I’ve performed simple analyses like this a few times before, but not since the college-going rate started its precipitous decline.

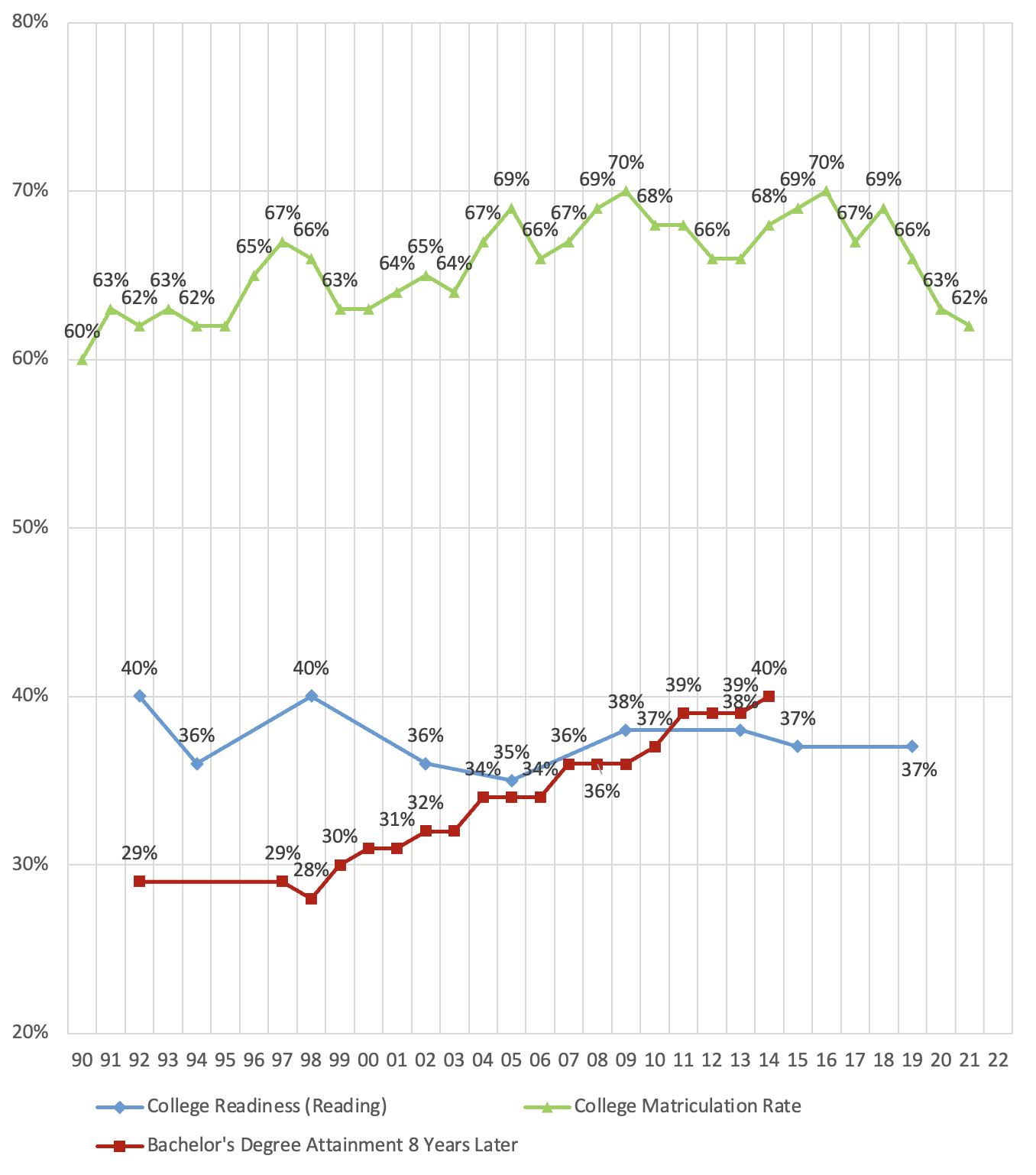

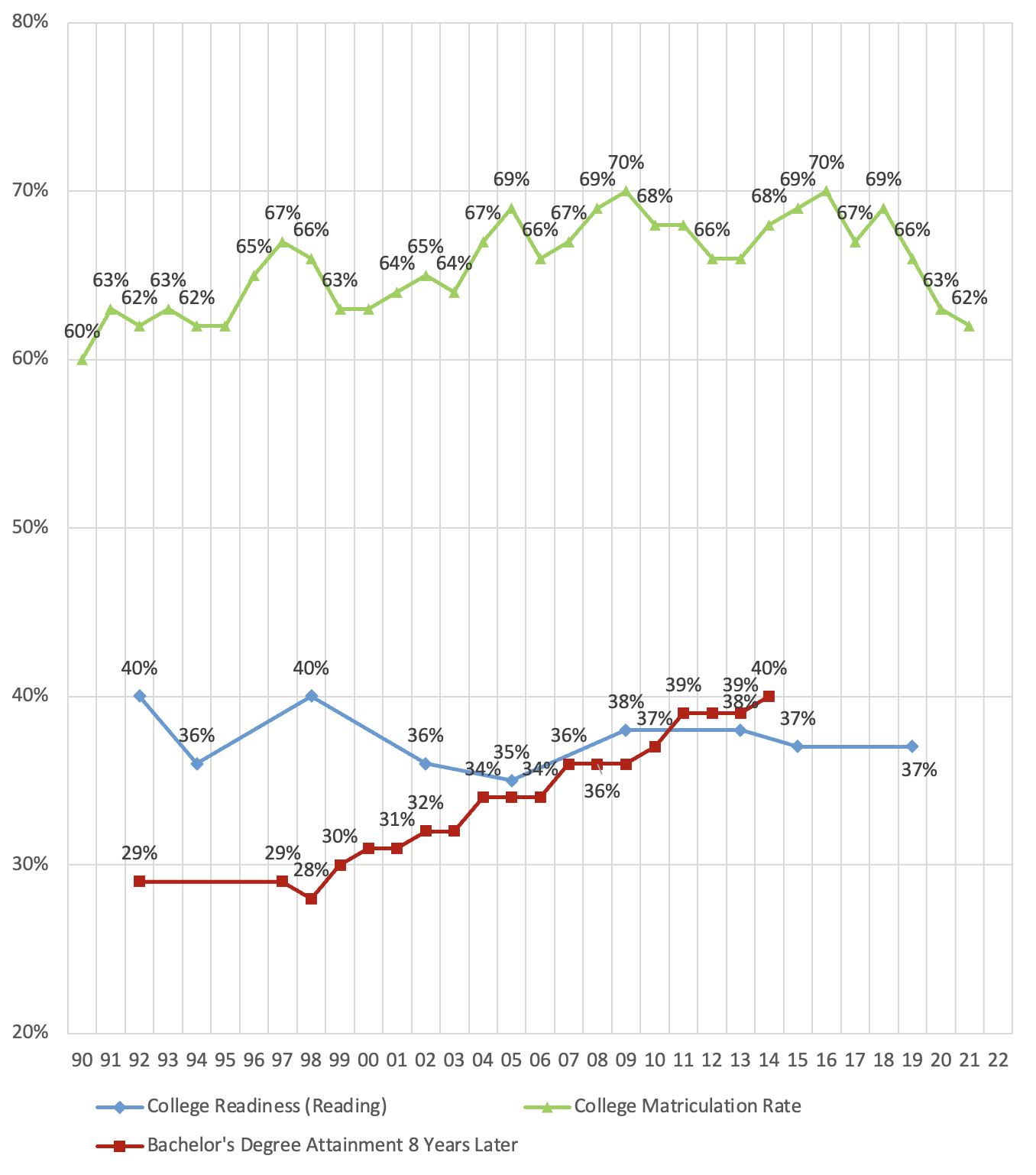

Chart 1 displays the percentage of twelfth-graders in a given high school graduating class who reached the National Assessment’s “college-prepared” level in reading over the past three decades, which, according to the National Assessment Governing Board, equates to “proficient.”

Chart 1 also shows the percentage of students in that same high school graduating class who matriculated directly to college, as well as the percentage of that class that eventually graduated with bachelor’s degrees within eight years. The most recent college completion data come from 2022, for the high school class of 2014. See the notes at the end of this post for data sources.

Chart 1: College preparedness, college matriculation, and college completion

What we can see here, for example, is that 40 percent of the high school graduating class of 1992 scored at the college-ready level in reading; 62 percent of this class matriculated directly to college; and 29 percent completed a four-year degree. More recently, 38 percent of the high school graduating class of 2013 scored at the college-ready level in reading; 66 percent of this class matriculated directly to college; and 39 percent completed a four-year degree.

There’s good and bad news here. The good news is the incredible increase in the proportion of young Americans completing at least a bachelor’s degree—10 percentage points over two decades, or an increase of about a third in real numbers. Even if some of this represents “degree inflation,” that’s substantial, life-changing progress.

The bad news is twofold. First, over the entire time series, our college-matriculation rate is much higher than our college-readiness rate. This means that almost a million students every year have been heading to postsecondary education even though they weren’t college ready. That’s a lot of Jills—and a lot of student debt.

Second, though it has bounced around a bit, our college-readiness rate has been essentially flat for more than three decades. And that was before the pandemic. When the next batch of twelfth grade scores are released, they will surely be lower than what we see here.

And what to make of the most recent trends? Starting with the high school class of 2011, we see the college-completion rate nudging ahead of the college readiness rate. What that means is that some students who weren’t college-ready, at least according to NAEP’s benchmark for reading, still managed to get four-year degrees.

The positive read is that these underprepared students worked hard, and perhaps their colleges did too, beating the odds, and proving that NAEP’s college-ready measure shouldn’t be taken as too definitive. The negative take is that college standards may have dropped to such a point that even students who struggle with reading comprehension can earn a four-year diploma. On balance, though, it seems to me that college readiness will likely continue to place an upper bound (even if it not a firm one) on college completion. If we want more kids to graduate from college, our K–12 system needs to get more students ready for college. And post-pandemic, we are instead heading in the opposite direction.

As for the recent declines in the college-matriculation rate, they are significant and may actually be encouraging—again, provided that the kids newly forgoing college are Jills and not Jacks. And it’s clear that there’s still a considerable distance for the college-going rate to fall, if we only want students who are college-ready (or close to it) to give postsecondary education a try. The gap between our most recent college-matriculation rate (62 percent) and our most recent college readiness rate (37 percent) is a whopping 25 points. That’s down significantly from 2009, during a terrible labor market, when 70 percent of high school graduates went straight to college. But that gap could be, and should be, much smaller.

Education has a terrible habit of swinging from one extreme to another. Here’s hoping that, when it comes to the question of college versus career, we can avoid making that mistake. The numbers here demonstrate the need for a “college for all students who are ready to succeed in it” movement. Who’s in?

Sources:

The college matriculation numbers come from the National Center for Education Statistic,’ Digest of Education Statistics, Table 302.20.

In reading, the National Assessment Government Board estimates that “college-prepared” is equivalent to “proficient.” So these numbers are the percentage of all twelfth-grade students who were proficient in reading in those given years.

Bachelor’s degree completion numbers come from the Digest of Education Statistics, Table 104.20: “Percentage of persons twenty-five to twenty-nine years old with selected levels of educational attainment, by race/ethnicity and sex: Selected years, 1920 through 2022.

Special thanks to Meredith Coffey and Jamya Davis, research interns at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, for collecting these data.