Shortly before schools—and Fordham—shuttered their doors for the holiday break, Tim Daly asked a simple question in these pages: Should schools ban smart phones?

It has been a hot topic of debate recently, and the growing consensus is that the correct answer is a resounding “yes.” Editorial boards from the Washington Post to Bloomberg have run op-eds and influential professors have published open letters arguing for stricter phone policies in schools. A majority of parents support rules that limit student access to phones, worrying that their children overuse social media, and only 16 percent of teachers believe that phones positively impact student development.

And we’re already seeing policy changes. Many districts, some states, and even entire countries have passed laws restricting access to phones during the school day. Perhaps the most notable statewide policy is Florida’s recent law that requires schools to prohibit phone use during class time and block access to social media via the school’s Wi-Fi.

None of this is entirely new. Limitations on the use of personal technology in schools reach back at least to 1989, when Maryland forbade the use of pagers and “cellular telephones” during school hours. Since then, public opinion and school rules have waffled between restriction and leniency. In the latest cycle, after a wave of techno-optimism saw schools rolling back restrictions, only 65.8 percent of schools prohibited their use during 2015–16. That share began to tick up as the effects of social media and screen time on teen mental health became clear.

This latest wave of policies present not unprecedented limitations, but stricter ones and novel approaches: homeroom teachers collecting phones and locking them up as students walk in the door; devices placed in Yondr bags at the building’s entrance; and policies that carry a consequence with the first infraction. Before, in practice, according to a Common Sense Media survey, “prohibition” covered a wide range of policies with uneven enforcement that was often left to teacher discretion.

The evidence in support of stricter policies is mounting. Several studies have confirmed that limiting phone usage during class increases performance on both standardized test scores and end-of-course exams. The gains were equivalent to an additional hour of instructional time per week. Restricting phone use outside class time also shows benefits. For example, when schools place limitations on them during recess, researchers found that students exercise far more, burning off energy, fostering physical health, and promoting later attention in class.

These findings make intuitive sense. At the cognitive level, all new information enters our brains through our working memory, the doorway to long-term memory. If that doorway clogs up with Temple Run sneakily played between textbook pages or with emotional anticipation and consideration of that fateful buzz, telling a student that their crush just texted back, students cannot focus on class content, in which case they won’t learn much of it.

I’ve worked at schools with both lenient and strict cell phone policies. At the former, it was a constant battle. The lunchroom was an eerie sight to behold: students sitting shoulder to shoulder with their necks craned down, their faces faintly lit, occasionally leaning over to show their friend a funny meme or TikTok video but never glancing up. There was little eye contact.

At the “phone ban schools,” however, the lunchroom had a healthy, boisterous energy. Students said “good morning” as they walked down the hallway. They looked and smiled at each other and their teachers. There were moments that required enforcement, but power struggles over phones were actually fewer at schools with stricter bans. Most kids complied; only a few were repeat offenders.

It seems clear that this latest trend towards stricter cellphone bans is a positive one. But how to get them right?

There’s a surprising analog with the science-of-reading movement here. Though there’s a rare point of both political and academic consensus on the benefits of explicit phonics instruction, it’s far from clear whether that agreement should result in policies altering curricula, teacher prep, grade retention policies, accountability measures, funding, or professional development; whether they’re best implemented at the classroom, district, state, or federal level; and whether more and better implementation comes via carrots or sticks.

So, too, with phones. The case for banning them is strong. Less clear are ideal policies. Do students turn them in to their homeroom teacher or can they keep them in their lockers? Are they allowed during lunch or passing time? What’s the consequence for an infraction and how quickly does it come about? How should this vary across elementary, middle, and high schools?

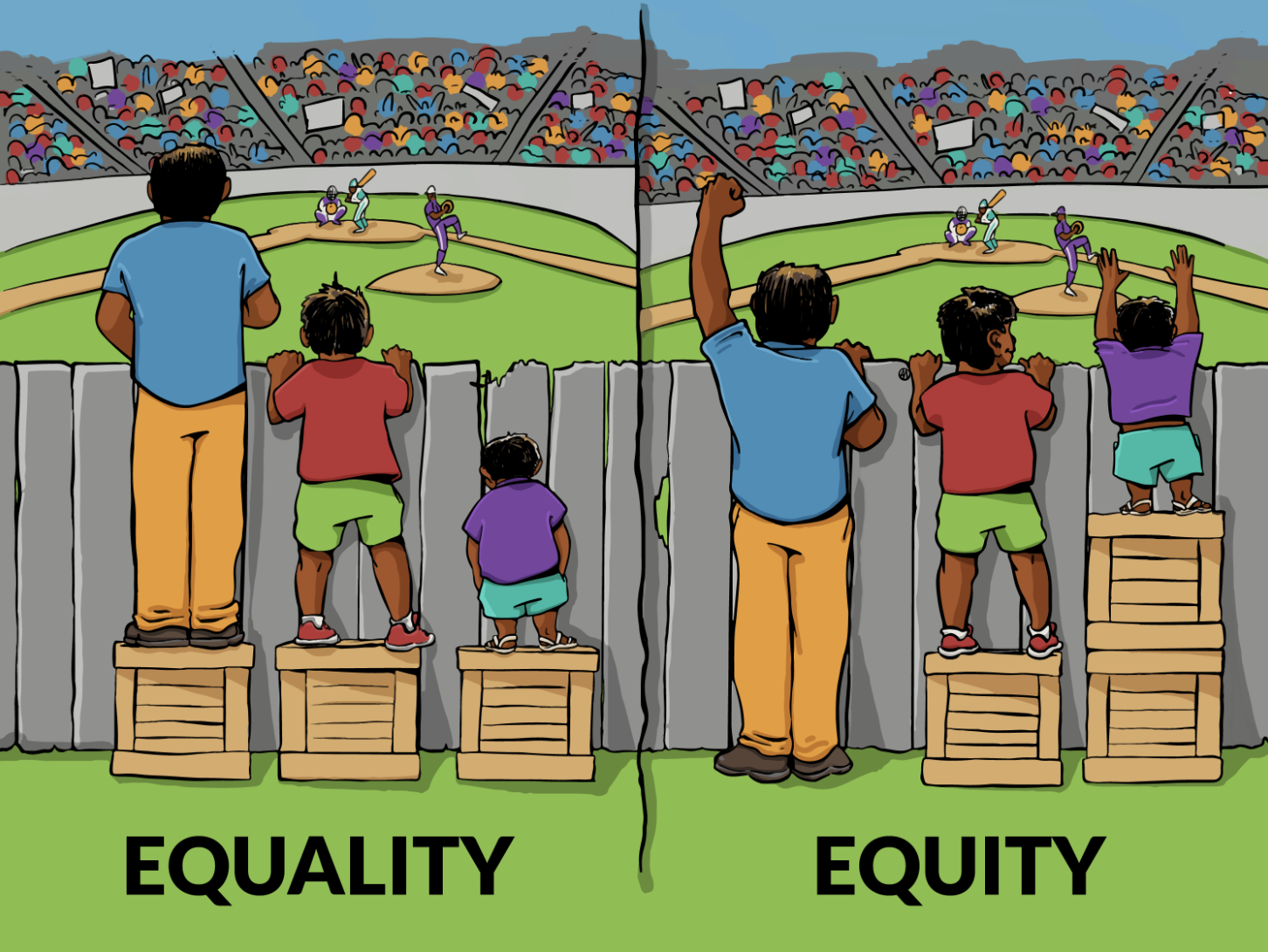

A hundred different policies can be imagined. But if it’s to succeed, any such policy must be based on three fundamental precepts: universality, enforcement, and a concurrent explanation to both students and parents, a PR campaign of sorts.

First, any policy must apply to the entire school. At my lenient school, administration left it up to individual teachers to choose when and if they would limit access to phones. Perhaps students had to put them away during instruction but could take them out for music during independent reading. One teacher might police their use, while another across the hall incorporated phones into the lesson. Human nature being what it is, there was an inbuilt incentive to be the lenient, cool teacher, which naturally prompted power struggles: “But Mr. Jay lets me use my phone in math!”

Second, it has to be enforced. Currently, schools are moving in the direction of behavioral permissiveness, rolling back discipline codes and consequence structures. But that can’t work for a phone ban. If a teacher confiscates one that’s being used in violation of the policy, a consequence must always follow. If not, it creates an all-win/no-lose scenario. A student always stands to benefit from uncertainty; most will take the risk of not turning in their phone.

I remember confiscating a student’s phone midday last year and watching my principal return the phone to the student a few hours later, in flagrant violation of our school’s own policy that parents must pick it up. What does that communicate to everyone in the building? The rules won’t really be enforced, what a teacher says can be ignored, and any adult who tries to enforce rules or student who follows them is a chump.

But the uniform consequence can’t be too complicated or it won’t always happen. One approach is to say that any usage gets a phone confiscated, the student receives a lunch detention, and a parent must pick up the phone. Fencing left unbuilt or full of holes provides no benefit.

Finally, some sort of PR campaign is essential. Comparisons abound between social media and hard drugs—“It’s digital fentanyl!”—but a better comparison might be cigarettes. The harms of heroin have always been clear, but fifty years ago, there was little popular knowledge of tobacco’s detrimental effect on the body. It was thought of as a light stimulant like coffee with little negative risk, so why not light up?

It’s the same story with phones. A phone provides access to friends, entertainment, and intrigue, so if a student doesn’t understand the harm of overdosing on screens, they’ll resent the bans. If they receive a few lessons on its detrimental impact, they’re more likely to buy in—however begrudgingly. Similarly, the inability to easily contact their children or the need to drive to school to pick up their child’s confiscated phone may disgruntle parents. But a few information meetings justifying the rollout will help to change minds. Concurrent with the restriction on smoke-free public spaces and higher ages for smoking was a national campaign of ads and school lessons on the harms of cigarettes. Cellphones require a similar effort.

When schools are permissive, children develop habits of inattention. They’re talking to friends while watching videos; they’re watching teachers while they have music in their ears; they’re completing math problems with a few rounds of candy crush between sets or reading a book with their phone on their desk.

Learning takes effort and sustained attention. Unfortunately, dopamine hits of social media have trained students to flee effort in search of easy, cheap entertainment.

The consequences of this rewiring are clear: stymied pandemic recovery, misbehavior, and tanking emotional health among teens. It’s time schools get serious and take away phones already.