“Twenty-five years ago, there was no proof that something else worked. Well, now we know what works. We know that it’s just a lie that disadvantaged kids can’t learn. We know that if you apply the right accountability standards you can get fabulous results. So why would we do something else?” —Jonathan Alter, “Waiting For Superman” (2010).

When I sat in a Manhattan theatre watching Waiting For Superman a decade ago, fresh from the classroom and new to the world of policy and education reform, the haughtiness and arrogance implicit in Alter’s words made me bristle. A decade later, it’s almost poignant. Did we actually believe ten years ago that America’s education problems were a simple matter of getting “accountability standards” right? That “we know what works”? Were we ever that naïve? I saw the movie with a friend who was not in education and found the film persuasive, even moving. My own response, which has since become my mantra, was “Well, it’s more complicated than all that.”

Ed reform circa 2010 was riding a cresting wave, but in retrospect it was the high-water mark. When the decade began, reform was playing offense, energetically aligned against an intransigent blob, armed with moral authority, bracing and seemingly durable bipartisan support, and a strong (if naïve) faith in the capacity of higher standards to yield broad student gains, a muscular testing and accountability regime, and enhanced choice, mostly in the form of charter schools. And all of it supported by a vast army of philanthropists and advocacy groups.

Ten years later, nearly all of this has been reversed or is in retreat. Big reform is dead. As the decade draws to a close, it takes an extraordinary level of self-deception to believe that the roots of education’s persistent and frustrating malaise are merely structural, that there are vast reserves of untapped capacity or competence in K–12 education awaiting marching orders, or that technocrats far removed from the daily work of teaching and learning hold the keys to unlocking it. This was foreseeable and foreseen. “While public policy can make people do things, it cannot make people do those things well,” wrote Rick Hess in National Affairs back in 2014, the year, not incidentally, that every American student was going to be reading and doing math proficiently by federal law. Policymakers do not run schools, Hess concluded, “they merely write laws and regulations telling school districts what principals and teachers ought to do,” and noting with understatement “there is often a vast distance between policy and practice.”

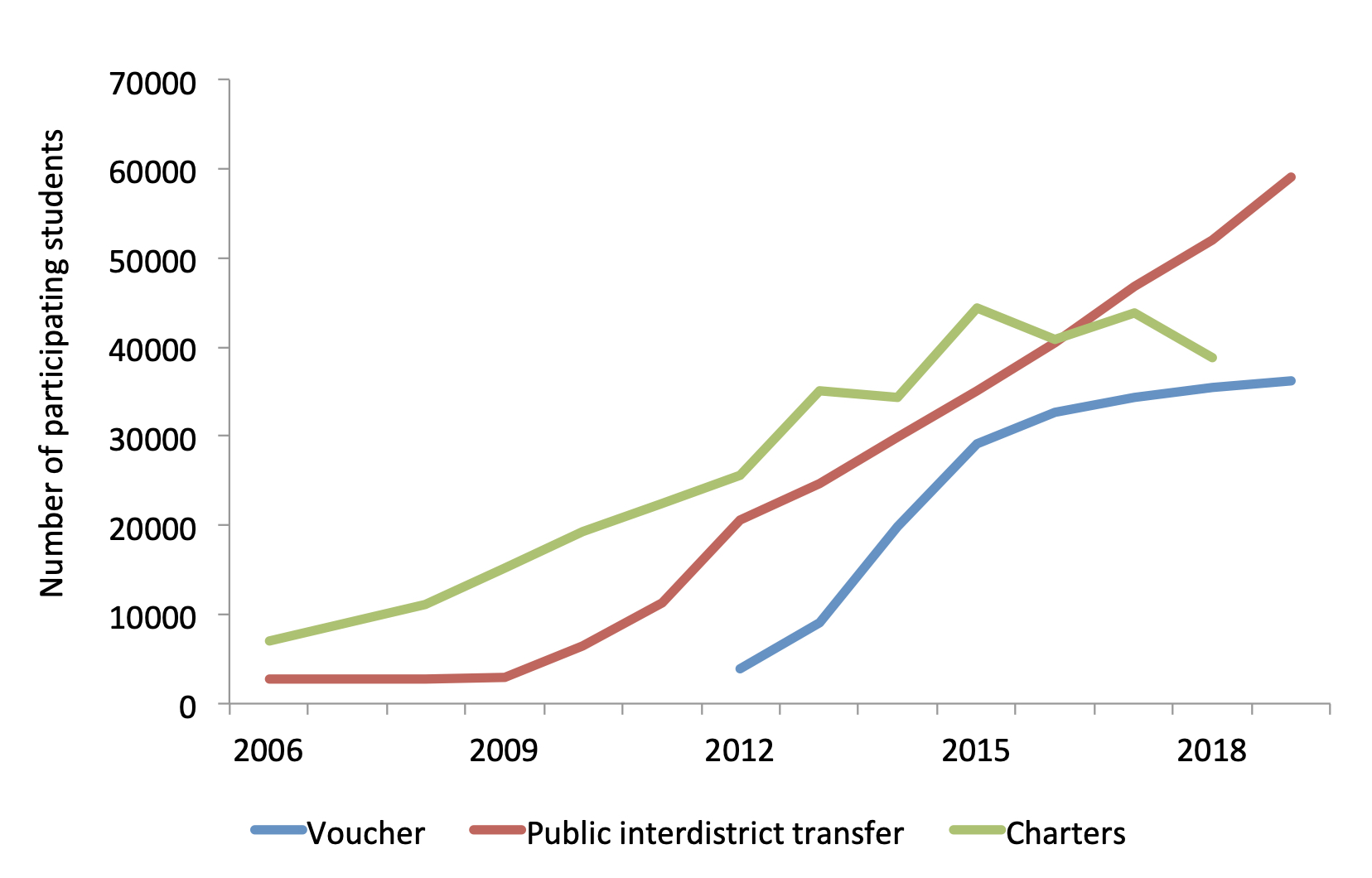

More recently, Stanford University political scientist Terry M. Moe offered an equally dour view of the inevitable failures of structural reform in his new book The Politics of Institutional Reform. Intransigent vested interests, including teachers unions, school boards, superintendents, and administrators, have no incentive to reform and reliably block it at every turn. “And so here we are,” Moe said recently on Russ Roberts’s podcast EconTalk. “It's 2019. How many kids are in charter schools? About 6 percent nationwide. How many kids have vouchers or use tax credits? Less than 1 percent nationwide.” And accountability? It’s “run into a buzzsaw with the unions hating accountability and being threatened by it,” he explained. Meanwhile Republicans are “getting back to their local government roots and getting all teary eyed about how important it is to have state and local governments run everything.” That means returning accountability to state and local governments to die. “So I think here we are, after all this time, and we've made very, very little progress,” he said.

Moe’s sobering analysis understates the intransigence of the problem. Even where barriers to reform have been limited, the gains wrung from the reform playbook have still been modest. “We all know people that say some version of, ‘Well, we know what to do, we just don't have the will to do it,’” said Mike Goldstein, a self-described “humbled technocrat” and founder of Boston’s acclaimed Match Charter schools, in an interview. “But a lot of times our best examples of gains are shown in careful studies to be much smaller than what we had hoped or thought might be possible.”

Echoing Goldstein is City Fund’s Neerav Kingsland, formerly the head of New Schools for New Orleans, who wrote on his blog this week that “doubling or tripling the postsecondary success rate for low-income students is no small feat. This could help change the lives of millions of students. But this is far below the results I hoped for when I got into this work. I imagine many of my peers feel the same. And I am sure families want more for their children.”

Looking back not just over the past decade but to the dawn of the reform era circa 1983 and A Nation at Risk, it is nearly inconceivable that anyone would view where things stand today as a victory—or even acceptable progress for thirty-five years of effort. The logic of Big Reform and its focus on testing, standards, and accountability assumed that schools and teachers know what to do and that technocratic engineering could deliver a sufficient shock to the system to make them do it. It hasn’t worked. And let me preview my 2029 ed reform retrospective: If the past decade has convinced you that the real problem in American education is institutional racism, segregation, and the broad array of social ills that have diverted education reform’s attention from its core business of teaching and learning, and that those things need to be fixed first, gird your loins for another frustrating decade.

Here’s some holiday heresy as the decade draws to a close: One lesson of the past decade may be that if reducing poverty is your public policy goal, education might not be your primary strategy. Your efforts might be better focused incentivizing work, strengthening families, shoring up personal income, or on housing and health care policy. “Education is life changing for scores of young people, and is a critical policy lever. But at scale, we’ve often approached education as the lever, the Holy Grail for poverty alleviation. The gains, even in the best of circumstances, haven't match our ambitions at the outset,” Paymon Rouhanifard, the former superintendent of schools in Camden, New Jersey, said in an interview. “This speaks to the complexity of poverty.”

In the zero-sum game of education policy debate, much of the above will be read as an indictment, even surrender—an argument that the battle is over and that ed reformers should fold their tents and go home. It’s not, for the reason suggested by Rouhanifard. There have been encouraging developments, notably networks of high-achieving urban charter schools serving tens of thousands of low-income black and brown children whose lives would be poorer without them. They are success stories that ed reform should defend (particularly as Democrats have all but abandoned charter schools and the parents who rely on them), but even the brightest stars in the charter school world are not compensation enough for the broader lack of gains. So much reform, so little to show for it.

Education reform’s reach has exceeded its grasp, but that’s not an invitation to sentimentalize a golden pre-reform era that never existed, nor to throw up one’s hands and quit the field of battle. Moreover, there’s a difference between a cynical anti-reform, just-send-more-money argument, and a thoughtful stance that is clear-eyed and humble, that holds on to its aspirations while recognizing its limitations. We don’t have permission either as educators, policymakers, or citizens to write off boxcar numbers of American children. But neither should we indulge ourselves, digging in our heels and continuing to advocate for policies that we know aren’t effective simply because we don’t want to show weakness publicly.

So where does this leave ed reformers other than chastened and humbled? If the decade to come is to be different than the one now drawing to close, it suggests more modest expectations, situating reform’s center of gravity closer to the ground (read: focusing on practice improvements, not mere structural reform) and in enhanced school choice with parental satisfaction at least as important a measure of success as test scores. Elsewhere in this issue, my optimistic colleague Dale Chu argues that the decade now drawing to a close, for all its Sturm und Drang, has been a good one for choice. He looks at the same sobering data Terry Moe cited above and sees one million more students in charter schools than in 2010, and an additional 400,000 participating in private school scholarships. That’s a long way from scale, or a rising tide lifting every child’s boat, but it’s not nothing—particularly for the low-income, black, and brown families who are its primary beneficiaries. I’m inclined to think that along with a focus on improved curriculum and pedagogical practice, defending and growing school choice in all its forms—not just the ones technocrats encourage and favor—is a more modest and appropriate focus of reform energy in the next decade.

And perhaps as good as it gets.