Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

“Less than 10 percent of the U.S. STEM workforce is Black or Hispanic,” says a recent study by Penn State’s Paul Morgan and colleagues, even though they make up 32 percent of the population. It rightly points out two reasons this is a problem: It reduces the country’s scientific innovation and economic competitiveness, and it lessens the earning potential of Black and Hispanic Americans, as the career income of those who major in STEM are 26–40 percent higher than comparable peers in other fields.

This is consistent with other research, including the work of Raj Chetty, an economist at Harvard. According to a 2019 study he did with Alex Bell and colleagues, “Drawing more low-income and minority children into science and innovation could increase their incomes—thereby reducing the persistence of inequality across generations—while stimulating growth by harnessing currently under-utilized talent.”

In another 2018 study Chetty and colleagues conducted, they found that, compared to White peers, Black and Hispanic Americans are significantly more likely to fall behind their parents economically, and are significantly less likely to exceed them. The situation is especially dire for Black children: When their families are in the top fifth of the income distribution, only 18 percent will remain there as adults; and when their families are in the bottom fifth, just 2.5 percent will make it to the top fifth. For White children, those figures are 41 percent and 10.6 percent, respectively.

This matters for schools, says Morgan et al., because “very high levels of STEM proficiency during adolescence are strongly related to STEM doctoral degree completion and knowledge production.” In other words, boosting the science and math proficiency of our young Black and Hispanic students would likely improve their economic mobility, as well as America’s scientific innovation and economic competitiveness. So, using the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–11, the research team set out to better understand these gaps in elementary school—in particular, when they emerge, how large they are, how stable they are throughout those six years, and how well twenty-two different student, family, and school factors explain them.

In short, they find that Black- and Hispanic-White disparities, defined as the percentage of students in each subgroup in the overall top 10 percent of science and math achievement: (1) already exist when students start kindergarten; (2) are sizable, between 9 and 11 percentage points; (3) are quite stable from grades K–5, all the years the study examines; and (4) are pretty well explained by those twenty-two factors.

It’s an important and interesting study, and you should read it in full, but I found three takeaways particularly noteworthy.

1. Those student, family, and school factors explain most of the Hispanic-White gap, but not the Black-White gap, and the researchers aren’t sure why.

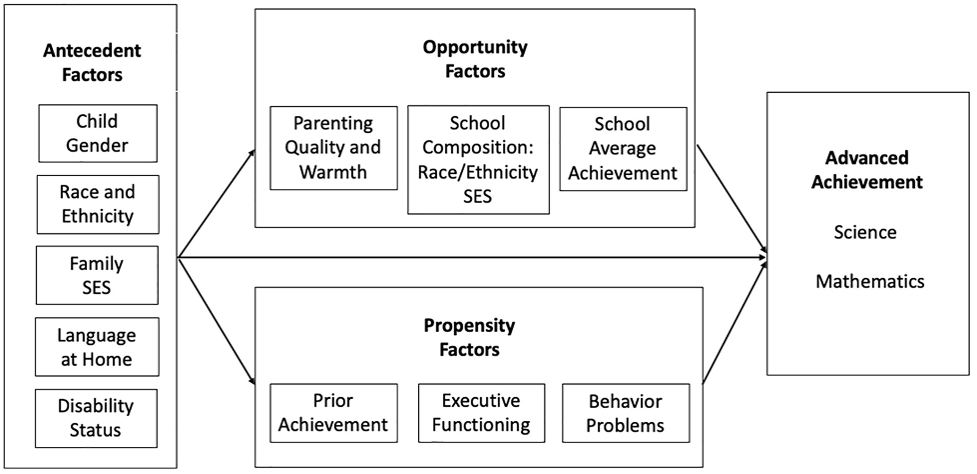

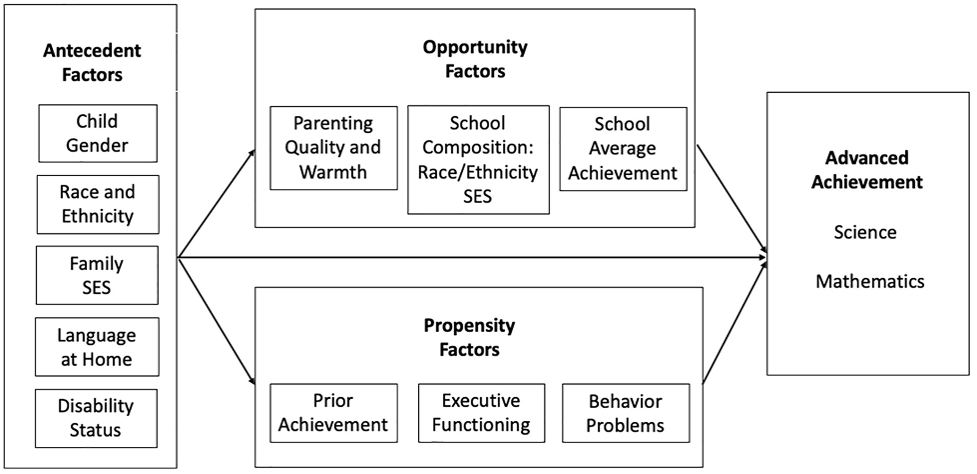

If the goal is to reduce these disparities in advanced achievement in math and science, we have to know why they exist. Is it family income? Prior achievement? School quality? Parent effects? Systemic racism? The team did this by looking at “antecedent, opportunity, and propensity factors influencing advanced achievement,” which they note is a “well-validated theory of achievement growth.” They illustrated the framework with the following figure:

They found that the factors “mostly explain” the Hispanic-White disparities, but that the Black-White disparities “were not fully explained and remained both practically and statistically significant.”

They note that this is consistent with other work, citing a 2004 study by Roland Fryer and Steven Levitt, which found that “Black- but not Hispanic-White achievement gaps in reading and mathematics among observationally similar kindergarten students increase over time.” Fryer and Levitt also weren’t sure why.

Morgan et al. say this needs to be studied further. And indeed it does.

2. Students who speak multiple languages at home were more likely to achieve at advanced levels in math and science.

The researchers found that “non-English-language use in the home repeatedly predicts a greater likelihood of displaying advanced science or mathematics achievement.” This is consistent with other work, including a 2014 study by Andrea Stocco and Chantel Prat and a 2018 study by Andree Hartanto, Hwajin Yang, and Sujin Yang.

Indeed, the 2018 study, which used two large U.S. datasets, found that “bilingualism positively predicted teacher-rated mathematical reasoning, emergent numeracy skills, and test scores on either mathematical word problems or standardized mathematical assessments.” The link persisted as children transitioned from kindergarten to first grade.

Morgan et al. hypothesize that “bilingualism may facilitate the learning of the complex rules and procedures integral to supporting advanced STEM achievement.” It does this, suggests the 2014 study, because of the “need to flexibly select and apply rules when speaking multiple languages.”

Perhaps this is why, as Morgan’s team points out, “Children who are English language learners have been reported to be more likely to be identified as gifted during elementary school,” citing a large-scale 2020 study.

3. Further support for the “big-fish-little-pond” theory.

This theory claims that students at schools with higher average math achievement “may adopt lower self-concepts, leading to lower effort and achievement in science and mathematics by the affected students,” according to Morgan et al. And this is consistent with what they found: Children attending elementary schools with higher math achievement were less likely themselves to be high achievers—objectively, not relative to their classmates—a sort of negative peer effect. The impact was as strong as attending a school with a high rate of poverty, as defined by the proportion of students eligible for free lunch. In fact, only race, ethnicity, and gender were more significant negative factors.

This is also consistent with a 2008 study by the University of Oxford’s Herbert Marsh and colleagues, which found that the big-fish-little-pond effect is “remarkably robust, generalizing over a wide variety of different individual student and contextual level characteristics, settings, countries, long-term follow-ups, and research designs.”

—

I’ve long argued that advanced education is important for two reasons. One, it helps maximize the potential of participating students, which is something every child deserves. And two, in better developing the talent of these advanced students, it supports America’s economic, scientific, and technological prowess in an increasingly competitive global market.

And for just as long, I’ve lamented how poorly American schools have done this for America’s low-income, Black, Hispanic, and Native American children—all of whom are less likely to participate in advanced education programs and achieve at advanced levels.

This research on science and math achievement and the STEM workforce starkly demonstrates all of this—the gaps, their causes, and their consequences. The good news is that such dire findings often serve as a call to action. And in better understanding why these disparities exist and persist, we’re better able to identify, develop, and test solutions.

———

QUOTE OF NOTE

“My analysis indicates that gifted and talented programs are a small or negligible contributor to racial segregation in U.S. elementary schools. Eliminating all gifted and talented programs nationally would have a minimal impact on standard measures of racial segregation, and the presence of a gifted and talented program does not appear to causally impact the racial composition of enrollments over time.”

—Owen Thompson, “Gifted and Talented Programs Don’t Cause School Segregation,” Education Next, January 31, 2023

———

THREE STUDIES TO STUDY

“Self-Regulated Learning and Motivation Among Gifted and High Achieving Students in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Disciplines: Examining Differences Between Students From Diverse Socioeconomic Levels,” by Nurit Paz-Baruch and Hnade Hazema, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, OnlineFirst, January 28, 2023

“Self-regulated learning (SRL) is an active process that assists students in managing their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to navigate their learning experiences successfully. The study examined the differences in motivation and SRL between gifted and high achievers (GHAs) and typical achievers (TAs) in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines by addressing the contribution of socioeconomic status (SES)… The results indicated that among GHAs, all motivation measures were significantly higher than those of TAs, especially among students from low-SES environments. GHA students reported using more SRL strategies than TA students regarding organization, metacognition, time and learning environment, peer learning, and effort regulation. Students from low-SES environments reported using more organization strategies than those from high-SES environments, whereas TA students surpassed their GHA counterparts in critical thinking.”

“Prospective Teachers’ Beliefs About Human Intelligence in a Turkish Sample,” by Fatih Kaya, M. Talha Kaya, and Sumeyye Kaya, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, OnlineFirst, January 27, 2023

“Research consistently reports a moderate to a strong relationship between intelligence and academic performance. For about a century, the concept of intelligence has often been used in the definition of giftedness and the identification of gifted students along with other data sources, although some experts are against it. An understanding of prospective teachers' beliefs about intelligence is important to unearth how they perceive intelligence and giftedness. We replicated Warne and Burton's (2020) study with 157 prospective Turkish teachers… Like the original study, the Turkish sample showed an understanding of the relationship between education and intelligence; however, the items about biological and genetic influences on intelligence, the plausible causes of group differences, the life outcomes of intelligence, and a cross-cultural comparison of intelligence had a low response uniformity in both studies…”

“‘You Are so Smart!’: The Role of Giftedness, Parental Feedback, and Parents’ Mindsets in Predicting Students’ Mindsets,” by Michiel Boncquet, Jeroen Lavrijsen, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Karine Verschueren, and Bart Soenens, Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 66, Issue 3, April 2022

“Although it has been hypothesized that gifted students are at risk for adopting a fixed mind-set, research revealed inconsistent results. We aimed to clarify this by differentiating between two operationalizations of giftedness (high cognitive ability and formal identification as gifted) and how these relate to students’ beliefs about intelligence and effort. Also, we examined the role of parental antecedents on students’ beliefs. Participants were 3,329 seventh-grade students and their parents. Only being labeled as gifted was related to adopting a fixed mind-set. Regarding parental antecedents, parents’ intelligence and effort beliefs were related to students’ corresponding beliefs. Furthermore, parental feedback was associated with students’ beliefs, which was most pronounced when student-reports of feedback were used. In particular, person-oriented feedback related positively to a fixed mind-set and negatively to students’ appreciation of the role of effort in academic performance, while process-oriented feedback showed the opposite pattern…”

———

WRITING WORTH READING

“Parents irked as Alpine School District cancels 3rd grade gifted program,” Daily Herald [Utah], Sarah Hunt, February 3, 2023

“Governor signs proclamation naming February as Gifted Education Month in Kentucky,” Kentucky Teacher, Joe Ragusa, February 2, 2023

“The College Board strips down its A.P. curriculum for African American Studies,” New York Times, Anemona Hartocollis and Eliza Fawcett, February 1, 2023

“NYC high school admissions is overwhelming. It rewards parents like me.” Chalkbeat New York, Bliss Broyard, January 30, 2023

“The emotional characteristics of gifted children,” Exploring Your Mind, José Padilla, January 30, 2023

“In memoriam: Marcia Gentry, scholar, friend, mentor, mother, and wife,” Gifted Child Quarterly, Sally Reis and Matt Fugate, January 27, 2023

“High expectations—and frustrations: Stories of twice exceptional students desperately seeking support,” ADDitude, ADDitude Editors, January 27, 2023

“Selective standards under scrutiny as NYC Council debates school admissions,” New York Daily News, Cayla Bamberger, January 25, 2023

“As my family found out, KY schools are denying services to gifted children,” Lexington Herald Leader, Barry Saturday, January 24, 2023

“Gifted Specialists fill broad needs of 20% of students,” Madison County [Alabama] Record, Gregg Parker, January 20, 2023