Staying on the shelf: Why rigorous new curricula aren’t being used

I want that quiet rapture again. I want to feel the same powerful, nameless urge that I used to feel when I turned to my books.

I want that quiet rapture again. I want to feel the same powerful, nameless urge that I used to feel when I turned to my books.

I want that quiet rapture again. I want to feel the same powerful, nameless urge that I used to feel when I turned to my books. The breath of desire that then arose from the coloured backs of the books, shall fill me again, melt the heavy, dead lump of lead that lies somewhere in me and waken again the impatience of the future, the quick joy in the world of thought, it shall bring back again the lost eagerness of my youth. I sit and wait. —Excerpt from All Quiet on the Western Front.

It’s Wednesday morning, first period, eighth grade English language arts. Ms. Jackson faces her twenty-five students[1] in Urban Center USA. She has fourteen years of teaching experience. Three months earlier, her principal had announced that the curriculum she had been using—more or less—for the last eight years would be replaced by a “high-quality, standards-aligned, EdReports green-labeled” curriculum.[2] Prior to the start of the semester, Ms. Jackson had received a day of professional learning on the new materials, followed up by an additional hour of “PD” a month ago.[3] In those sessions, she had been admonished by the district’s curriculum director to dig in and be sure to stay on pace with the new curriculum.

She was determined to try. But her challenges were considerable: Seventh grade assessment results told her that on average, her students were more than two years below grade level in reading. Ms. Jackson was reassured to find that, based on its Lexile level (a measure of difficulty), All Quiet on the Western Front was at the very low end of difficulty for the grade. But it would still be uphill work.

Today was to be a “Reveal,” meaning that “Students [should] go deeper into the text, explore the author’s craft and word choices, analyze the text’s structure and its implicit meaning.” She stared at the paragraph before them: rapture and reading, desire and lead, memory and futurity, the mental universe, the lead inside, figuratively, symbolically, literally?

She would start with the figurative language. She looked at the curriculum guide again—very minimal help there for her challenge.[4] An internet source from the Massachusetts Department of Education told Ms. Jackson the obvious: “Strategically plan instruction that incorporates previous standards into the lesson, for example: how to distinguish literal from figurative language.” Easy to say, but how to do it?

To add to her problems, today was observation day. Ms. Jackson’s principal was going to evaluate her teaching using the Charlotte Danielson framework. Ms. Jackson knew that her principal, a one-time math teacher, would plough through the list—“engaging students in learning,” “using questioning and discussion techniques,” “demonstrating flexibility and responsiveness.” There was nothing about actually teaching All Quiet on the Western Front. Neither would Ms. Jackson be given any credit in her evaluation for attempting to remediate her students’ lack of understanding of literary symbolism in the text in front of them.

What would be on the principal’s mind, however, were the results of a computerized Interim Assessment from the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) that her eighth graders had recently taken. Ms. Jackson recalled that among the many, many skills on which her students struggled was “8.L.5 Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.” Of course, the interim test had contained no reference to her curriculum material. Not one of her students would be tested on their understanding the “breath of desire” or the “dead lump of lead.” She had no idea if spending a class session on this specific language would or would not translate into her students’ successfully deciphering figurative language in some unrelated chunk of text used in the next curriculum-agnostic assessment—or the all-important summative assessment at the end of the term.

Ms. Jackson recalled the warning in the Common Core State Standards that “The Standards set grade-specific standards but do not define the intervention methods or materials necessary to support students who are well below…grade-level expectations.”[5] She knew the usual trajectory for such students: Send them to RTI (Response to Intervention)—a label given to the effort in thousands of schools to support students with learning challenges. Many of Ms. Jackson’s students were already receiving “Tier 2” support[6]—structured, assessed lessons on isolated vocabulary and skills such as “fluency stems” using “fluency strips.” Ms. Jackson knew that once subject to extensive RTI treatment, all attention to All Quiet on the Western Front would melt away, but maybe her students just needed to get back to the basic skills?

Ms. Jackson’s recalled her teacher preparation program and induction. Nothing she had been provided with had prepared her to translate a demanding text—this text in this curriculum—into teachable strategies that could be used to support her students’ as they struggled today. She was on her own, and had a choice to make.

Those “breaths of desire”—and the hope of deep, thoughtful engagement with great works of literature that inspired her district to adopt its “high-quality, standards-aligned, EdReports green-labeled” curriculum in the first place—would just have to wait.

—

When I and my New York State Education Department colleagues launched EngageNY in 2010, I could not have guessed that the materials would be used in some fashion by up to a third of math and a quarter of ELA teachers. EdReports, citing RAND data, indicates that “36 percent [of teachers] indicated they used EdReports “to identify, select, and implement instructional materials.” The Council for Chief State School Officers is several years into an eight-state project to support state education leaders in supporting their school districts’ transition to the use of High-Quality Instructional Materials.[7]

But any celebration is utterly misplaced. Availability isn’t usage, and usage “in some fashion” isn’t going to move the needle on student outcomes. Ms. Jackson’s story is going on across the United States, and it is negating efforts to implement high caliber curriculum across the country.

Ed Reports puts the matter succinctly:

Unfortunately, even as materials have improved, a significant challenge remains in ensuring districts are using the quality materials that are available. Our analysis shows that only a small fraction of students (22 percent in math and 15 percent in ELA) are exposed to aligned curriculum at least once a week.

Common sense suggests, and data confirms, that this isn’t going to achieve anything.

I predict that in the coming months, we will see more such findings to the effect that new high-quality curricula aren’t achieving much of anything for our less prepared students—and the critics are already vocal. My Johns Hopkins University colleague Bob Slavin holds nothing back: “Actual meaningful increases in achievement compared to a control group using the old curriculum? This hardly ever happens…. I am unaware of any curriculum, textbook, or set of standards that is proven to reduce gaps. Why should they?” Instead, he points to research on the positive effect of tutoring, which, as he points out, is curriculum agnostic.

Bob Slavin is an education research scientist: He looks at a single intervention, measures its impact, and reports. Marc Tucker, by contrast, is a systems thinker: He looks at the American education system, finds it deeply flawed, and argues that single interventions such as adopting a high-quality curriculum are likely to prove next to useless until enough of the entire system has been rendered coherent. In words that could have been explicitly addressed to high-quality curriculum interventions, Tucker writes:

The key levers of top performance in the countries with the best education systems don’t work in this country because they are not supported in this country by the other elements of policy that make them work in the top- performing countries.

It won’t surprise readers that the OECD finds that Singapore has some of the strongest curricula in the world. As the report makes clear, Singapore takes curriculum very seriously indeed: What you teach matters in Singapore. But that’s because teacher preparation, curriculum, and examinations, to mention but three key elements, work together so that strong curricular content can have the impact it should.

Our sobering tale of Ms. Jackson reveals that in the United States we have built a system that not only fails to support the sustained use of demanding curriculum—but actively produces powerful disincentives to its use. In what school of education are teachers prepared to teach powerful and demanding works of literature to students who are two or three grade levels below the level required to make real sense of those texts? (I know of none, but would like to be mistaken.) Is there a high-quality ELA curriculum that includes materials for teachers whose students are below grade level? In how many districts are principal evaluation tools supplemented by curriculum-specific rubrics? Beyond the quizzes and curriculum-embedded assessments, how many standalone interim assessments actually measure students’ knowledge of what their curriculum asks them to read? How many summative assessments do the same? Where can we find RTI models that are integrated with specific curriculum?

One state—Louisiana—is in the early stages of providing positive answers to some of these questions. Taking advantage of ESSA’s Federal Pilot Assessment Authority, the state is developing a combined interim and summative assessment grounded in its widely used ELA “Guidebooks” curriculum.[8] The state is starting—just starting—to focus on the implementation challenges of teaching this demanding, high-quality curriculum.

Elsewhere, not so much, or none at all. As TNTP’s recent report resoundingly reaffirms, “Students spent more than 500 hours per school year on assignments that weren’t appropriate for their grade and with instruction that didn’t ask enough of them—the equivalent of six months of wasted class time in each core subject.” And that’s on average: “Classrooms that served predominantly students from higher-income backgrounds spent twice as much time on grade-appropriate assignments and five times as much time with strong instruction, compared to classrooms with predominantly students from low-income backgrounds.”

Given these multiple, mutually reinforcing disincentives to teaching rigorous, grade-level materials profiled above, is it any surprise that over 95 percent of America’s teachers use multiple, self-curated internet materials mixed together in an utterly eclectic and incoherent fashion with their district’s curriculum?[9]

In the last decade, a few states, hundreds of school districts, and thousands of schools have taken seriously the responsibility to provide their students with challenging content that is worth learning, and thus worth teaching. But these pioneers are rowing upstream. Our policies must change to help, not hinder, them:

What we teach, and how well we teach it, are the core of any and every school learning experience, no matter the method used. Unless we incentivize teachers to teach demanding material well, most especially to underprivileged students, we will lose this vital opportunity to close achievement gaps and raise learning outcomes. We cannot afford to prove the obvious to ourselves one more time: that implementing an essential aspect of learning is a wasted effort in an incoherent education system.

[1] The average size of an American public middle school classroom.

[2] EdReports is a non-profit organization that evaluates curricula for their alignment with national standards. Green is the color they give to a curriculum that has a high degree of alignment. https://www.edreports.org

[3] Tom Kane and his colleagues found that on average, teachers receive 1.1 days of Professional Development on new instructional materials. https://cepr.harvard.edu/curriculum-press-release

[4] For example, the “Teacher’s Note” for Grade 8, Module 2, Lesson 32 suggests that “If students need a reminder about what constitutes figurative language, ask students to list types of figurative language and write their responses on the board.”

[5] “What is not covered by the standards.” http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/introduction/key-design-consideration/

[6] Tier 2 support is essentially a set of interventions for students who are not able to undertake grade level work despite some “supplemental instruction.” http://www.rtinetwork.org/learn/what/whatisrti

[7] Disclosure: The author is an advisor to this initiative.

[8] NWEA, Curriculum Associates, the National Center for Assessment, and my colleagues and I at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy are working with the Louisiana Department of Education to design and implement this assessment, currently at the middle school level.

[9] As Kathleen Porter-Magee wrote in Education Next in 2017, “A RAND study revised last April found that 98 percent of secondary school teachers and 99 percent of elementary school teachers draw upon ‘materials I developed and/or selected myself’ in teaching English language arts. And those materials are most often pulled from Google (96 percent) and Pinterest (74.5 percent). The results were similar for math.”

[10] In addition to NWEA’s work in Louisiana, Centerpoint recently announced that it was going to create interim assessments for Illustrative Math and EL (what used to be called Expeditionary Learning when it was first part of EngageNY).

All children deserve to attend schools that educate them to the maximum of their ability and open as many opportunities as possible for them. Poor or rich, black or white, high or low achieving, this is a goal we often hear espoused but seldom see achieved. The victims of this dereliction are broad and many, but the results of the 2019 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) give us good reason to focus once again on high achievers. They offer a bright spot on a generally gloomy horizon.

Most everyone has read by now about the dismal scores on our Nation’s Report Card, which again measured how fourth and eighth graders did in math and reading. Aside from fourth grade math, marks were generally flat or down, especially for our lowest-performing children.

The dismayed responses that followed were mostly justified. For those of us who spend our days striving to improve the achievement of young Americans, it was truly disheartening.

Yet a few bright spots emerged. In these pages, for example, my colleague Mike Petrilli and Chiefs for Change CEO Mike Magee detailed the heartening results in Washington, D.C., Mississippi, and Louisiana. Florida also posted some praiseworthy gains. All good, as far as it goes, but why is nobody remarking on the exceptionally strong performance of high-achieving children? Why are they yet again being ignored—and worse?

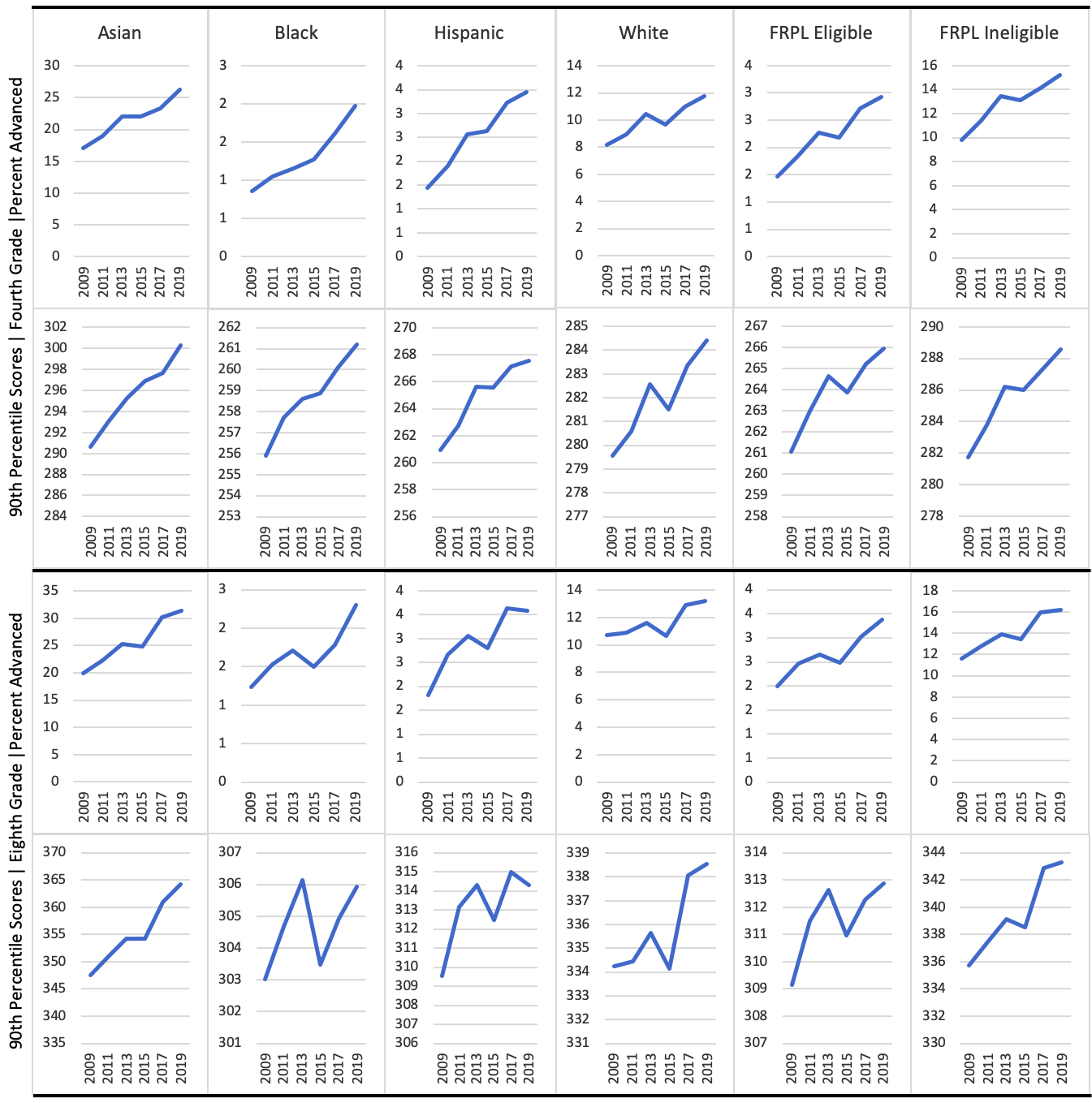

Check out figures 1 and 2, showing gains over the past decade by top-decile students and in the percentages of students attaining NAEP’s “advanced” level, which is legitimately thought of as “world class.”

The math picture, figure 1, is brightest. Notice how the trendlines, both shorter- and longer-term, are generally positive for children from all races and ethnicities, and regardless of economic status. That’s good. Period. It represents hundreds of thousands of students who are receiving a better mathematics education than they were in previous years.

Figure 1. Results of the 2019 NAEP, percentage of students achieving at advanced level and 90th percentile scores in math, by race and eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch

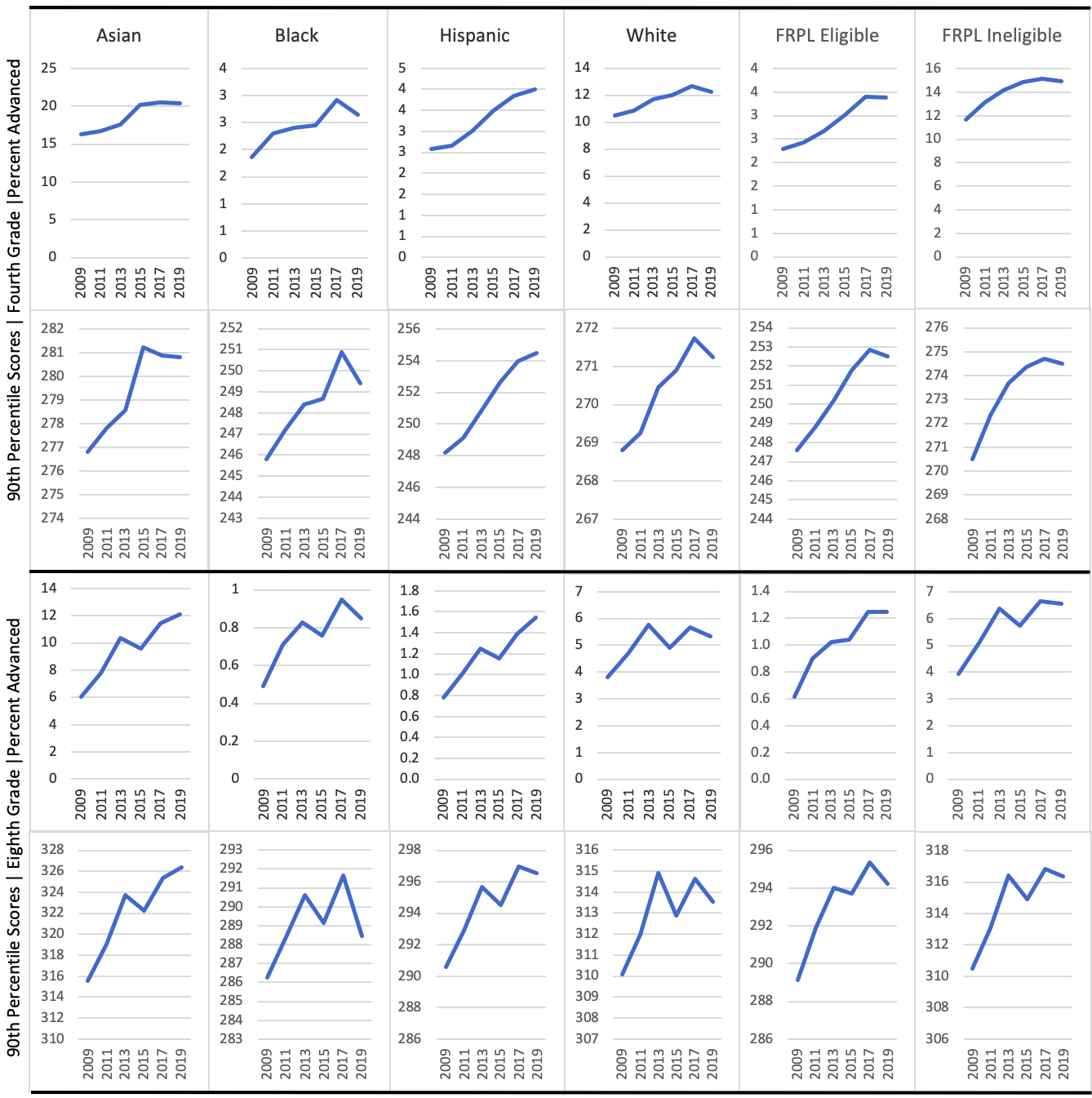

The results aren’t as positive in reading, especially in the short term, but figure 2 shows that there are bright spots there, too, notably among some disadvantaged groups.

Figure 2. Results of the 2019 NAEP, percentage of students achieving at advanced level and 90th percentile scores in reading, by race and eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch

Bear in mind that the black, Hispanic, and low-income students shown here are mostly disadvantaged, and are generally placed on the deficit side of achievement gap calculations. They’re usually among the have-nots when we talk about the haves. As such, they rely more than their advantaged peers on school to give them the skills, knowledge, and wherewithal to succeed in school, work, and life. Their gains should be applauded, the more so because they contrast with so many other of the NAEP results.

Yet that’s not been happening. Instead, they’ve been widely disregarded and sometimes even characterized as a bad thing. Consider this opening paragraph of a piece written by the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board lamenting the NAEP results: “The highest-achieving students are doing better and the lowest are doing worse than a decade ago. That’s one depressing revelation from the latest Nation’s Report Card that details how America’s union-run public schools are flunking.”

Sure, the faltering scores of low performers are a big and dire problem, especially in a land that yearns to narrow its achievement gaps. But it is unequivocally not depressing that our highest achievers are doing better. Nor should we consider the two outcomes—one positive and one negative—to necessarily be “flunking.” If a young student was improving in one subject but losing ground in another, would she be flunking school? I hope not. Success deserves praise and encouragement, while deficiency deserves attention and solutions. That holds, too, for our schools.

We must, of course, dig deeper into the unsatisfactory gains for some groups, even at the highest levels, and why many other groups are static or declining. Petrilli has theorized that “shifting academic standards dramatically higher, making the tests tougher, and pushing schools to adopt curriculum aligned to those standards and tests may have inadvertently left behind the lowest performing kids.” There are always tradeoffs. In the days of No Child Left Behind, almost all of the focus was on struggling students, and that harmed higher achievers. We may or may not have overcorrected. Some other constellation of policies and factors could be influencing the NAEP results more than we know. I encourage researchers and analysts across the country to search for answers.

Whatever the causes, however, the most recent NAEP results suggest at least two outcomes are clearly established. One is that we have far too many children achieving below their grade level, and we must intensify our efforts to change that. The other is that many schools are doing something right for their high-achieving students, and it’s benefiting kids from all races, ethnicities, and economic backgrounds. The first is a problem we must solve. The second is a good outcome that deserves praise and acknowledgment.

With less than a year to go until the 2020 presidential election, Elizabeth Warren’s ascendancy to ostensible Democratic frontrunner, and the release of her voluminously noxious education proposal, I fell into a fever dream of the same strain that afflicted AEI’s Rick Hess earlier this fall: I imagined President-elect Warren shaking hands with Randi Weingarten in the White House Rose Garden followed by an exchange between a glum reformer and a long-time union apparatchik who was giddy about the coming four years. Here’s the gist of the conversation:

Glum reformer: As a pro-reform Democrat, I’ve always been a fan of Elizabeth Warren. I didn’t care too much for her education plan, but I figured it was more about virtue signaling than actual policy. My hope was that after she became president, she would moderate her tone on education policy issues. Plus I thought DeVos was deplorable. But Randi Weingarten? Seriously?

Cheery unionist: What an acceptance speech! And a fiery one at that:

No more billionaire privatizers, no more school choice segregationists, no more corporate deforms, no more assaults on public education! Teachers are the heroes of our country, and your voices have been heard loud and clear. As Secretary of Education, I promise to work with the president-elect to make sure teachers are paid what they deserve, to end federal funding for charter schools, to eliminate the ability of states to pass right-to-work laws, and to stop the fixation on testing. The decades of top-down edicts and mass school closures are finally over.

Glum reformer: What about nominating someone with real teaching experience?

Cheery unionist: Promise kept! Randi’s a former high school history teacher. She mobilized teachers into Warren’s camp, and getting this nomination is just deserts.

Glum reformer: She still has to be confirmed though.

Cheery unionist: Shouldn’t be an issue now that we have control of both the House and the Senate. Did you hear that Randi has already called for a reauthorization of ESEA that does away with the requirement for annual testing?

Glum reformer: Ugh. You realize she’s also hellbent on putting the kibosh on charter schools, right?

Cheery unionist: I’ll let you in on a little secret. As someone who has an inside track into what the Warren administration is planning, they know there’s a limit to what they can accomplish legislatively, even with the federal government trifecta. Instead, Randi’s planning a death-by-a-thousand-cuts approach. Publicly profess large and lofty policy aims, but inside focus like a laser on mischief-making and gumming up the works.

Glum reformer: What do you mean?

Cheery unionist: Take the federal charter school grants program application. How many pages is it? To follow her new boss’s lead, Randi could push to quadruple its length and make the thing virtually unworkable. Yes, they’ll seek to dismantle it legislatively too, but it’s all hands on deck in the new administration to think creatively about pushing their regulatory authority. Here’s another potential target: charter authorizers. What’s the average length of a charter contract? Is there a way they can compel states to lower that time period? Create as much disincentive as possible to renew a charter contract, let alone open a new school. They could also promulgate guidance around fiscal impact—or something vapidly analogous—to provide more reasons for rejecting charter applications. Wrap all of this in rolls of red tape, and top it off with a bright, burdensome bow.

Glum reformer: In principle, I’m with Randi on a bunch of things like school discipline reform and LGBTQ students. But going after charters and choice is misguided.

Cheery unionist: You don’t get it, do you? Education reformers will never have enough manpower and political muscle to either protect or advance policies as long as you’re at each other’s throats. And now that we control the White House, the war of attrition is going to set you back even further. We’ll win by continuing to milk public opinion—the media eats up our homilies to underpaid teachers, teacher shortages, and low job satisfaction—and by working slowly and surreptitiously under the cover of regulatory darkness.

Glum reformer: And I thought things couldn’t get any worse.

Cheery unionist: The fox is in the henhouse. You’ve made your bed. I suggest you lie in it!

—

My delirium was shaken off after a sip of coffee, and an email appearing in my inbox with the subject line “Oneirophobia.” If Warren does end up winning the nomination, the sensible thing to do would be to return from the fringes and tack back towards the center. In which case, there’s little need to worry about my fever dream becoming anything more than just that.

A new study published in AERA Open investigates whether and to what extent racial discipline gaps are associated with racial achievement gaps in grades three through eight in school districts across the U.S. It also examines if these relationships persist after accounting for differences across districts.

The researchers combined data from the Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA), which contains achievement gap information for about 2,000 school districts nationwide, and the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC). They gathered achievement data from the SEDA and disciplinary data from the CRDC for the 2011–12 and 2013–14 school years, since these were the only two years for which a CRDC census of all U.S. public schools overlapped available SEDA data. They measured racial achievement gaps as district-level disparities between Hispanic and black students and their white counterparts, based on states’ math and English language arts standardized-test-score data. They used suspension counts by race for public schools that include any grade from third to eighth to measure the difference in out-of-school suspension rates between minority and white students.

Their key finding is that discipline and achievement data are indeed positively correlated for black and white students. A 1 percentage point increase in the black-white discipline gap is associated with a 0.01 standard deviation increase in the black-white achievement gap, and a 1 standard deviation increase in the achievement gap is associated with a 2.2 percentage point increase in the discipline gap. Put simply, districts with larger black-white discipline gaps have larger black-white achievement gaps, and vice versa.

Socioeconomic differences between black and white students could serve as one possible explanation for this result. That is, in districts where black students are much poorer than white students, on average, black students have both lower test scores and higher suspension rates. Although the authors do control for district-level racial disparities in the percentage of students who receive free and reduced-price lunch, it is doubtful that the socioeconomic data they had at their disposal could fully account for differences in family income by race.

Furthermore, the association between the black-white achievement and discipline gaps is partly explained by the tight coupling of achievement and discipline for black students specifically, who experience higher suspension rates in districts with larger achievement gaps and experience higher achievement in districts that suspend them less frequently. Because this tight coupling is absent among white students, the authors suspect that the mechanisms connecting achievement and discipline—e.g., teacher biases, peer effects, feelings of belonging—are more salient for black than white students.

While there is some evidence that Hispanic-white discipline gaps are positively related to Hispanic-white achievement gaps, this correlation did not hold after the inclusion of community-level characteristics (e.g., unemployment rate, college degrees held, median income) and district-level characteristics (e.g., percentage of English language learners, racial segregation, gifted and talented racial gap). In other words, the fact that the Hispanic-white achievement gap is wider in districts with bigger Hispanic-white discipline gaps is not due to the racial discipline gap, but rather to other differences between school districts.

This is the first rigorous empirical study to explicitly examine the relation between the racial achievement gap and the racial discipline gap on a national scale. Of course, the finding that there is an association between the achievement and discipline gaps for black and white students but not Hispanic and white students is purely descriptive, not causal. And because the analyses rely on data spanning grades three through eight, the results cannot be generalized to earlier or later grades. Still, the study sheds light on these racial intersections and offers hope in its implication that interventions aimed to close one black-white gap may have the potential to influence the other.

SOURCE: Francis A. Pearman II, F. Chris Curran, Benjamin Fisher, and Joseph Gardella, “Are Achievement Gaps Related to Discipline Gaps? Evidence From National Data,” AERA Open (October–December 2019).

A recent working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research looks at the effectiveness of two methods typically used to boost preschool quality—an infusion of funding and an increase in pedagogical supports—and surfaces some eye-opening results.

A group of international researchers studied the rollout of a nationwide program to improve the quality of education in hogares infantiles (HI), the public preschool system in Colombia. The HI program is the oldest public center-based childcare program in the country. It is targeted at families with working parents and enrolled an average of 125,000 children per year in the most recent decade. In 2011, the Colombian government announced a plan to upgrade HI program quality with a cash infusion representing a 30 percent increase in per child expenditures per year. The funding was to be used to purchase learning materials (books, toys, etc.) and to hire more staff, specifically classroom assistants, nutrition or health professionals, and professionals in child social-emotional development. The government provided some guidance for the proportions in which the money was to be spent, but HIs had some discretion within these guidelines. About two-thirds of the funding went to hire new staff.

In 2013, Colombian National University and NGO Fundacion Exito (FE) joined the effort by providing free education courses for HI teachers, including “technical guidelines for early childhood services; child development courses; nutrition; brain development; cognitive development; early literacy; the use of art, music, photography and body language for child development; mathematical concepts during early childhood; and pedagogical strategies during early childhood.” These courses were not mandatory, and HIs were free to participate as they wished.

Researchers were able to take advantage of the rollout structure for the new funding amounts and the free education courses to create three study groups—forty HIs that received only the government money (referred to as HIM), forty HIs that took advantage of the teacher education component and the government money (called HIM+FE), and a control group of forty HIs whose participation in either effort was delayed and thus continued business as usual over the study period.

Baseline data were obtained in mid-2013 from a sample of 1,987 children evenly distributed among the three study groups. Students were tested again eighteen months later, in late 2014. Researchers were able to assess nearly 92 percent of the students at both beginning and end, and the vast majority of those had persisted in the same HI center throughout the study period. Data were gathered in various areas of child development, such as cognitive and language skills, school readiness, and pre-literacy skills, as well as preschool quality and the quality of the home environment.

Compared to the control group, the HIMs saw no additional improvements in their students’ cognitive and social-emotional development despite the sizeable influx of cash. Some of the children in HIMs even lost ground as compared to their HI peers, especially in vital pre-literacy skills. However, in the HIM+FE centers, students realized statistically significant gains as compared to both of the other groups. Students from the poorest families notched the largest gains.

While it stands to reason that more funding and more teacher training would produce noticeable gains over the status quo, the question of how more funding by itself could produce negative results vexed researchers. After digging into teacher surveys, however, it became apparent that the new hires and “learning toys” were supplanting rather than supplementing HIM teachers’ interactions with children, leading to a decrease in actual teaching and learning.

These findings provide important evidence that education systems must spend money thoughtfully and strategically if true benefit is to accrue to the children in their care. Simply getting more funding with few strings attached can be counterproductive to the goal. But even more clear is that effective teacher training and professional development matters a whole lot in any setting.

SOURCE: Alison Andrew, et. al., “Preschool Quality and Child Development,” NBER Working Papers (August, 2019).

On this week’s podcast, Marty West, a Harvard professor of education, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to talk about last week’s NAEP results and their relationship to the Great Recession. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines how graduation requirements affect arrest rates.

Matthew F. Larsen, “High Bars or Behind Bars? The Effect of Graduation Requirements on Arrest Rates,” Education Finance and Policy (October 2019).