National achievement trends to watch when new NAEP scores are released next month (complete with 35 charts!)

By Michael J. Petrilli and Nicholas Munyan-Penney

By Michael J. Petrilli and Nicholas Munyan-Penney

This post is the second in a series of articles leading up to the release of new NAEP results on April 10. See the first post here. Future posts will examine state and local trends and identify the key questions that new NAEP scores will potentially answer.

The 2017 NAEP results will be released in April and will provide policymakers and analysts important data with which to track America’s academic progress or lack thereof.

To help us prepare, here’s a look at recent national trends, sliced and diced several different ways. In our view, the most helpful analyses:

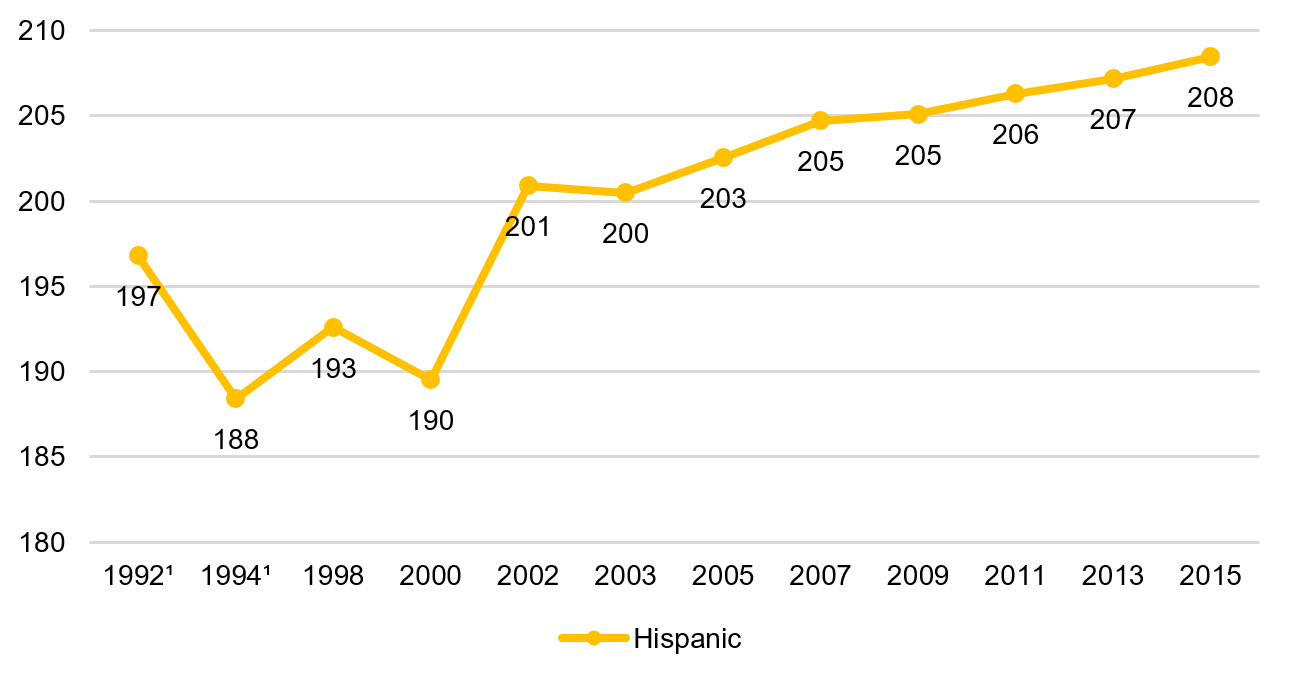

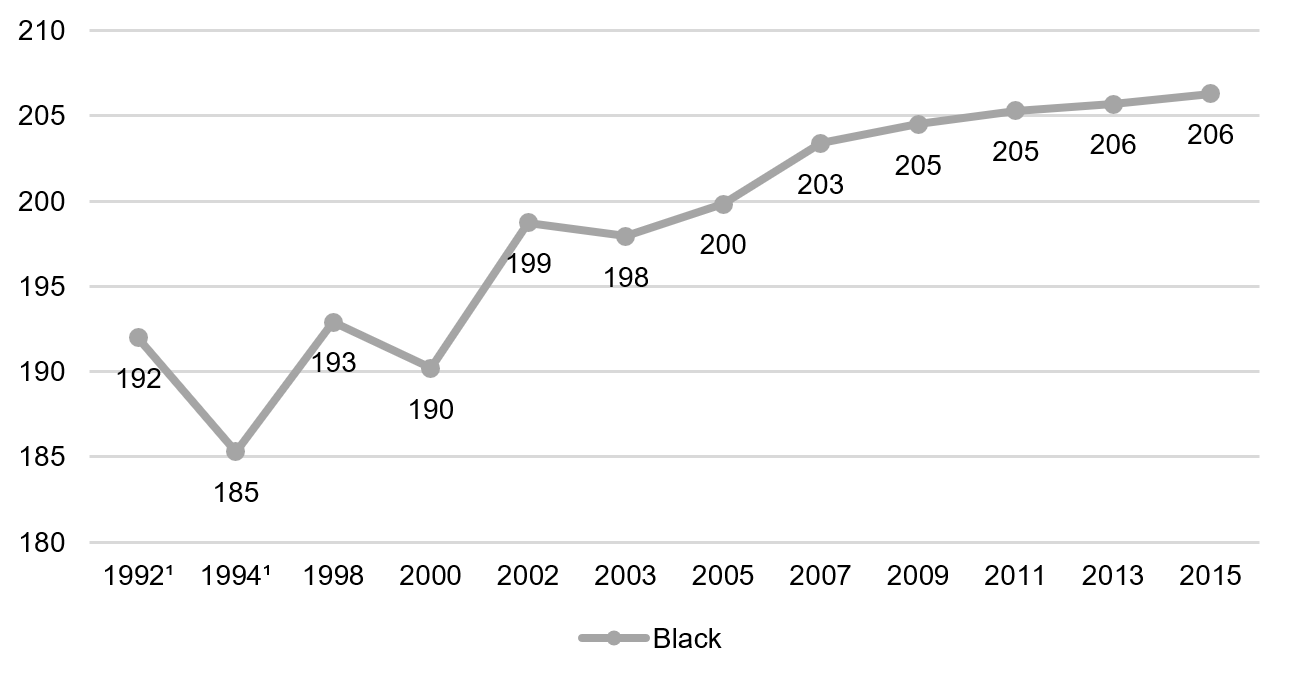

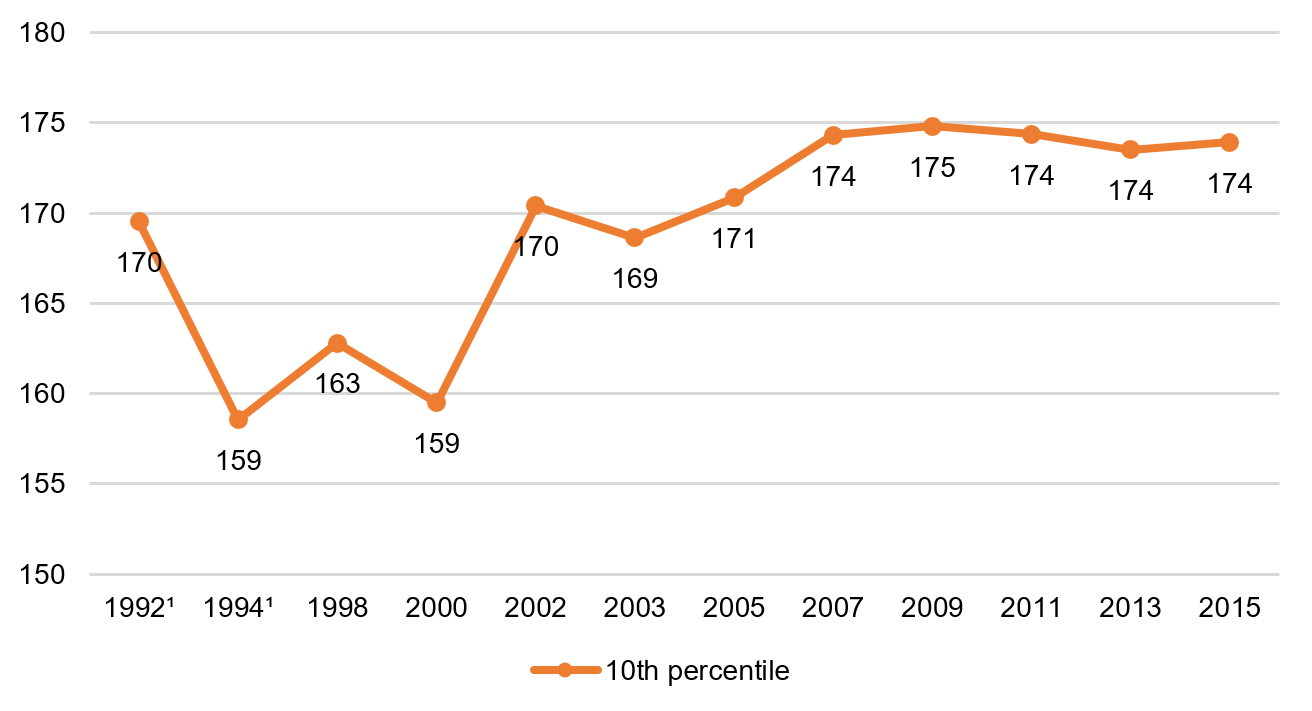

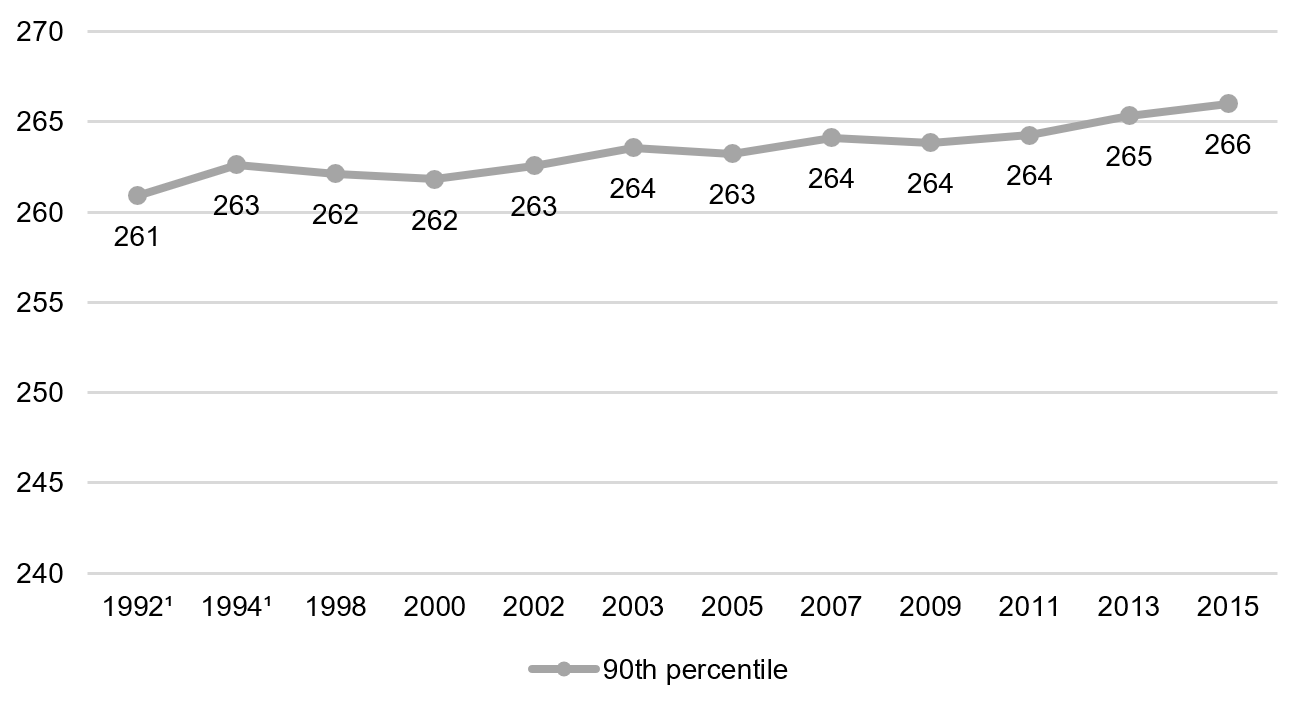

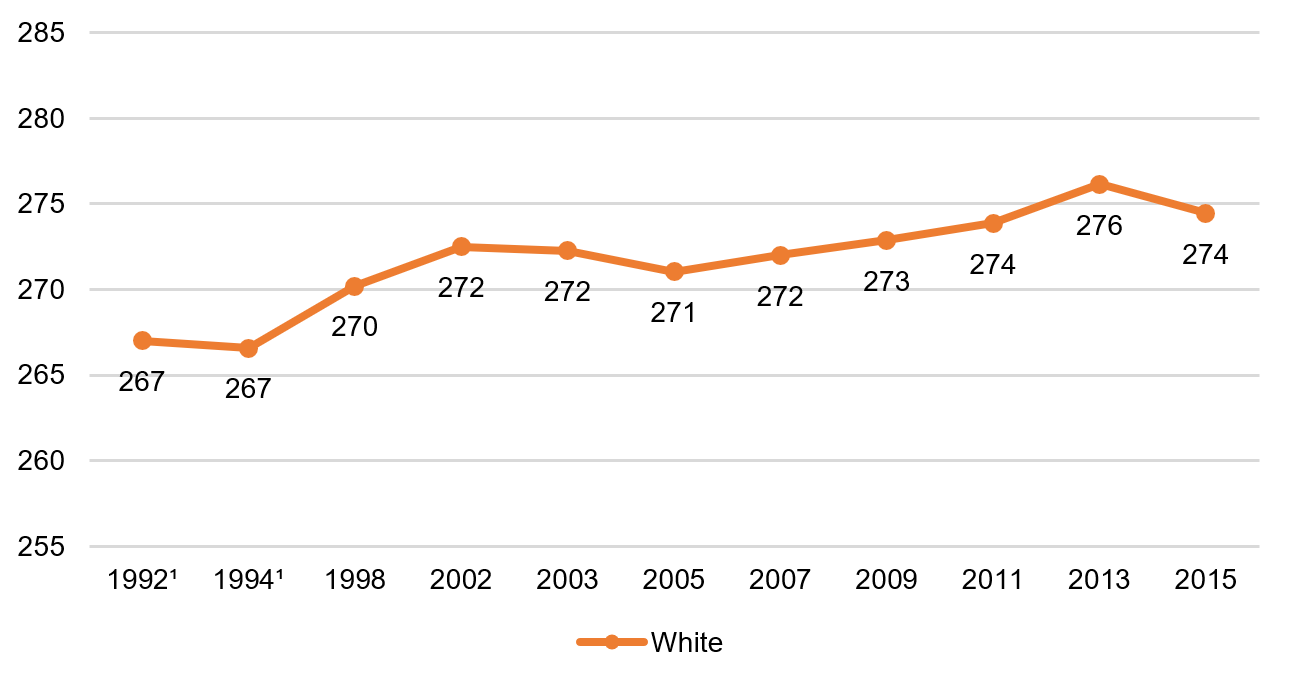

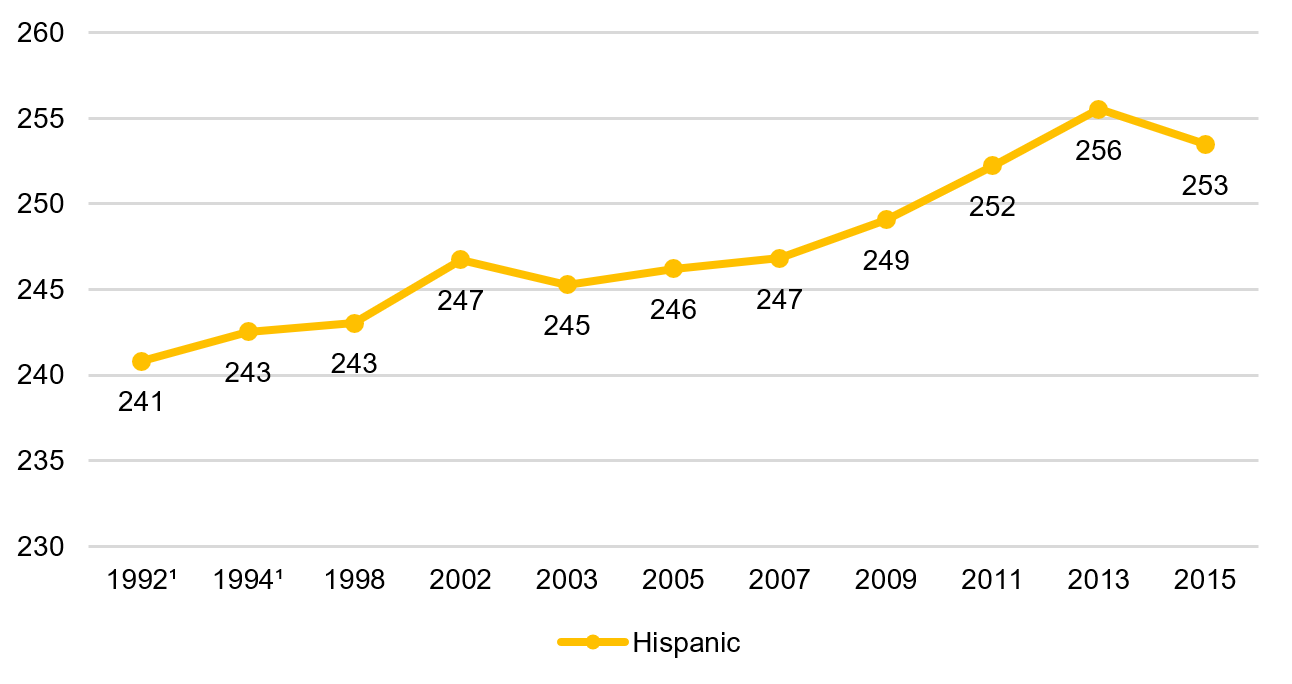

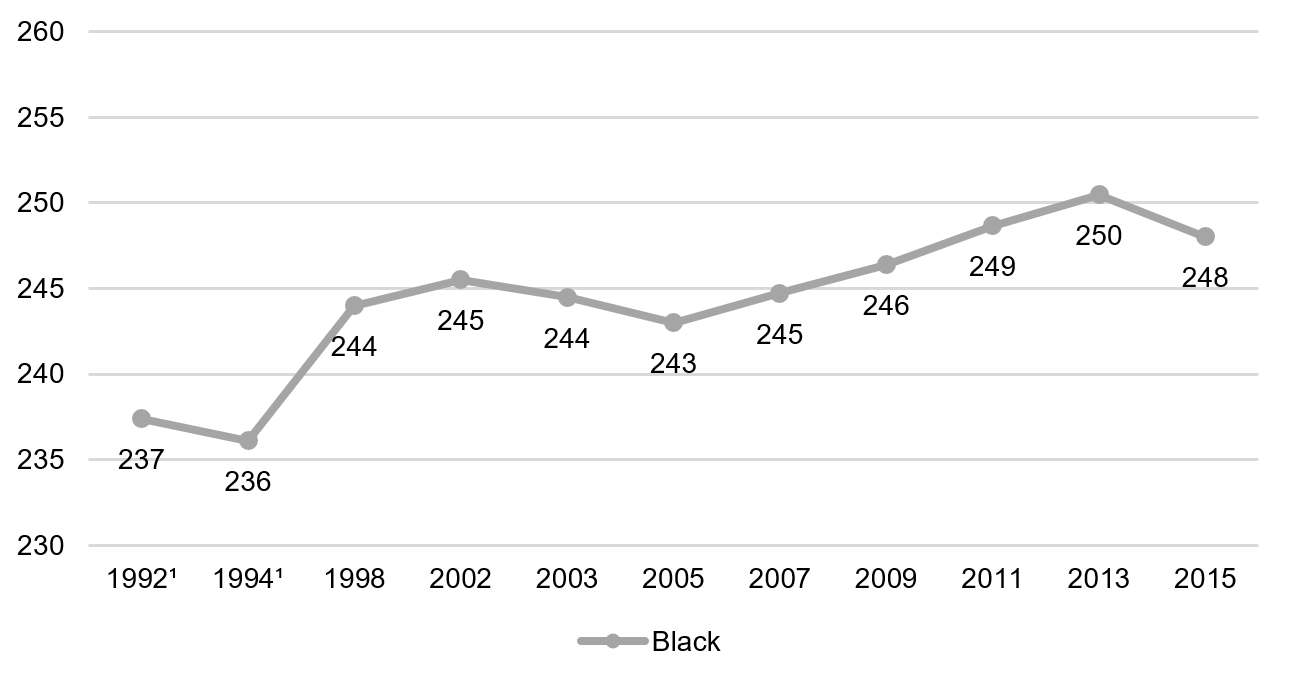

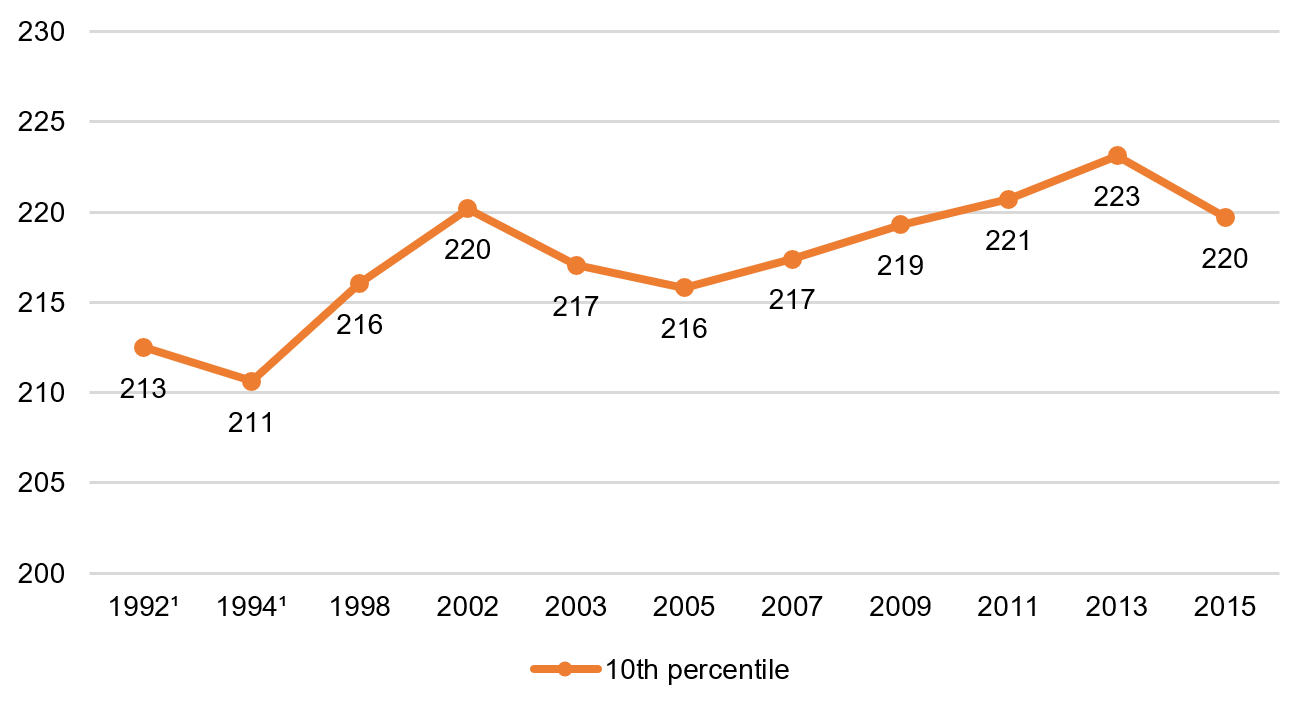

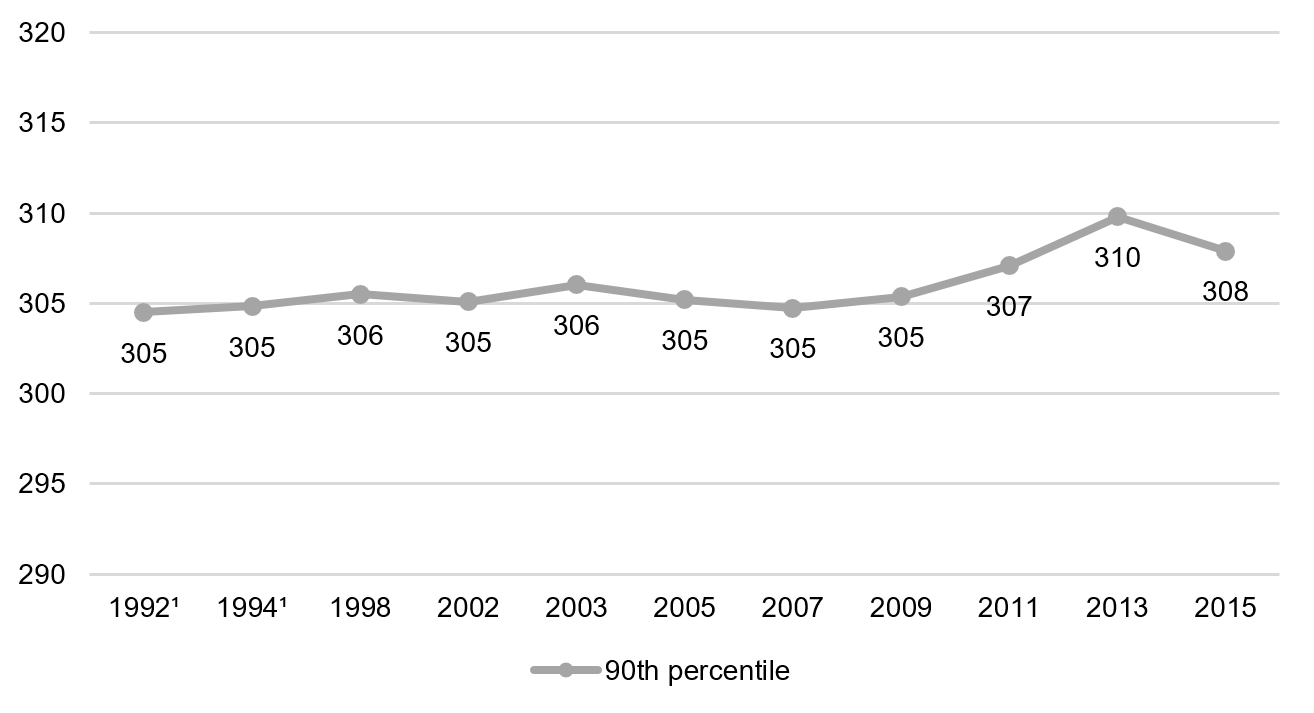

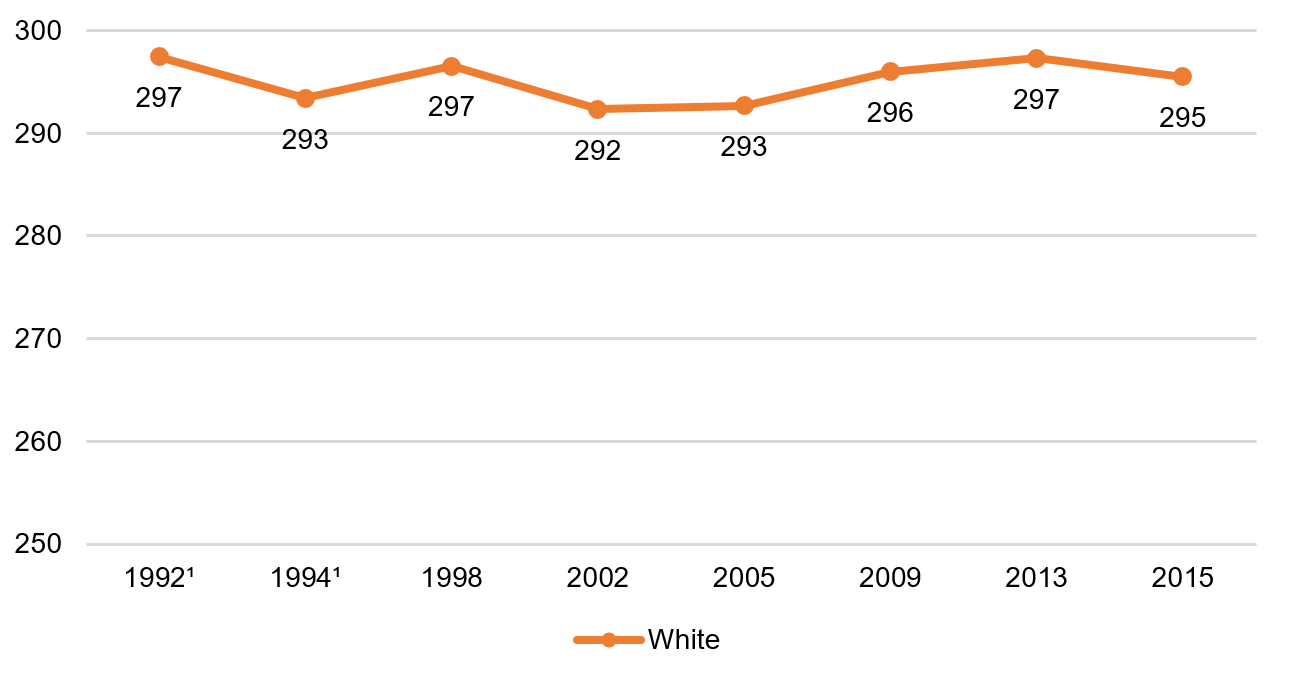

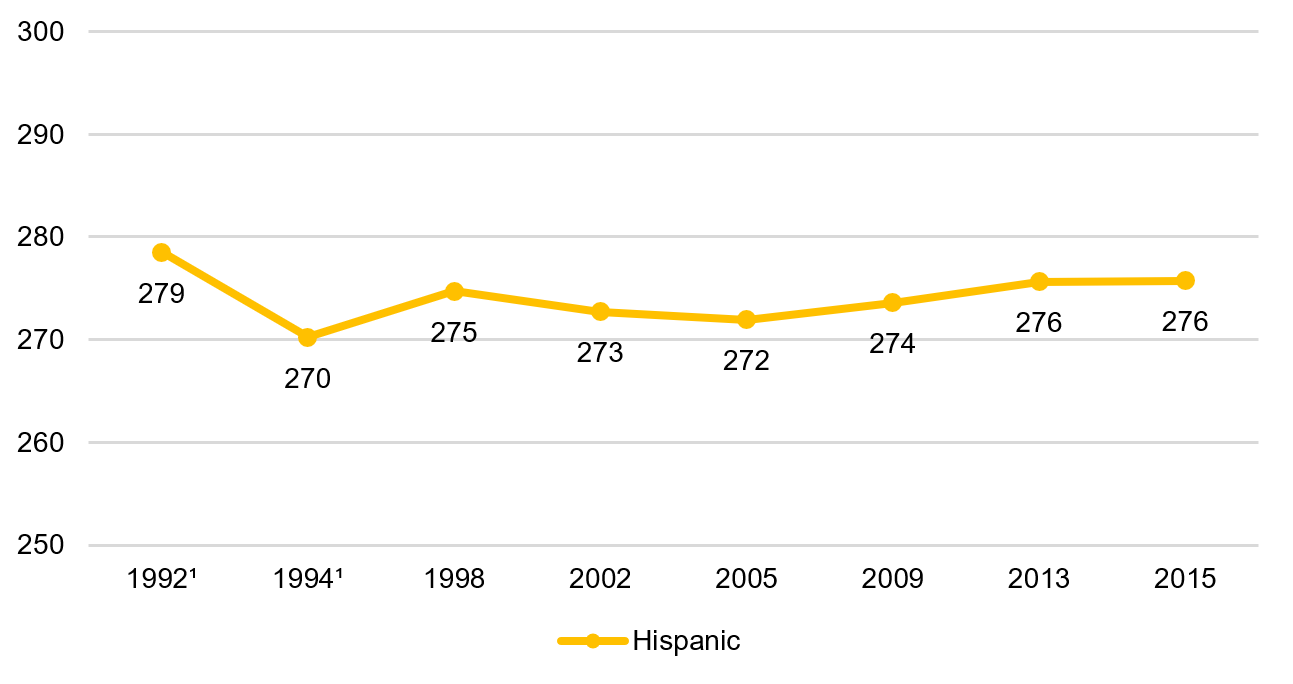

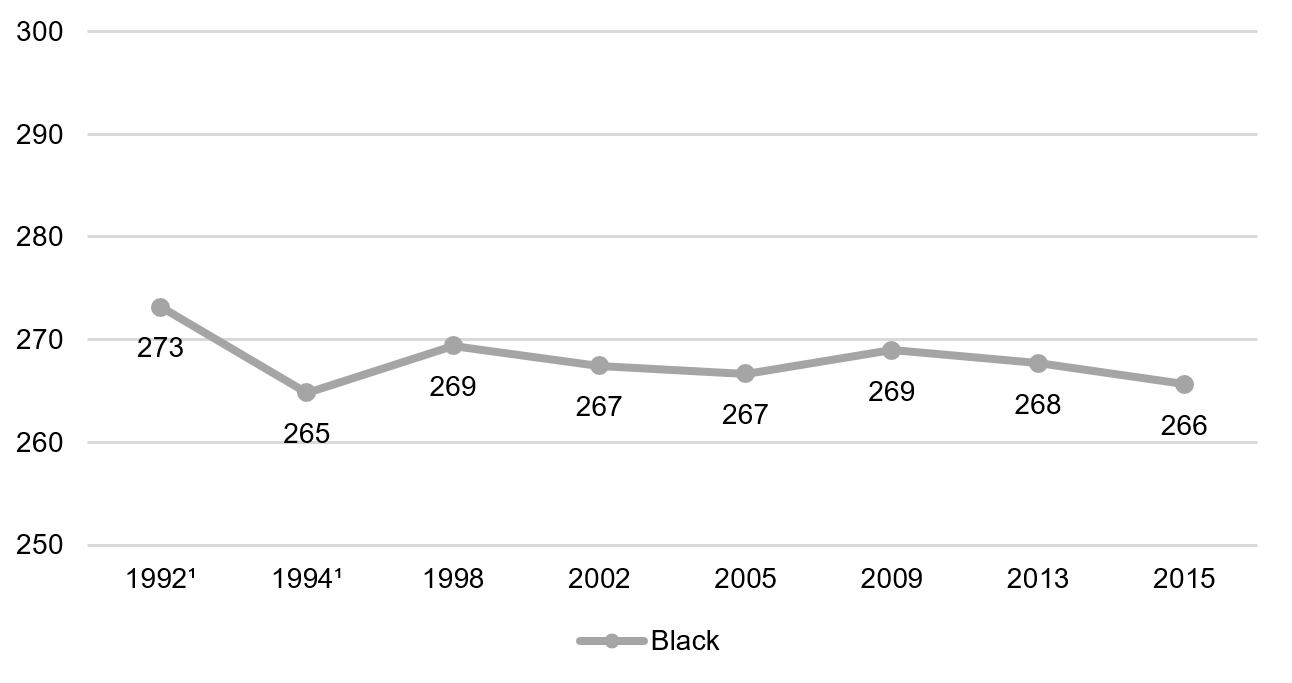

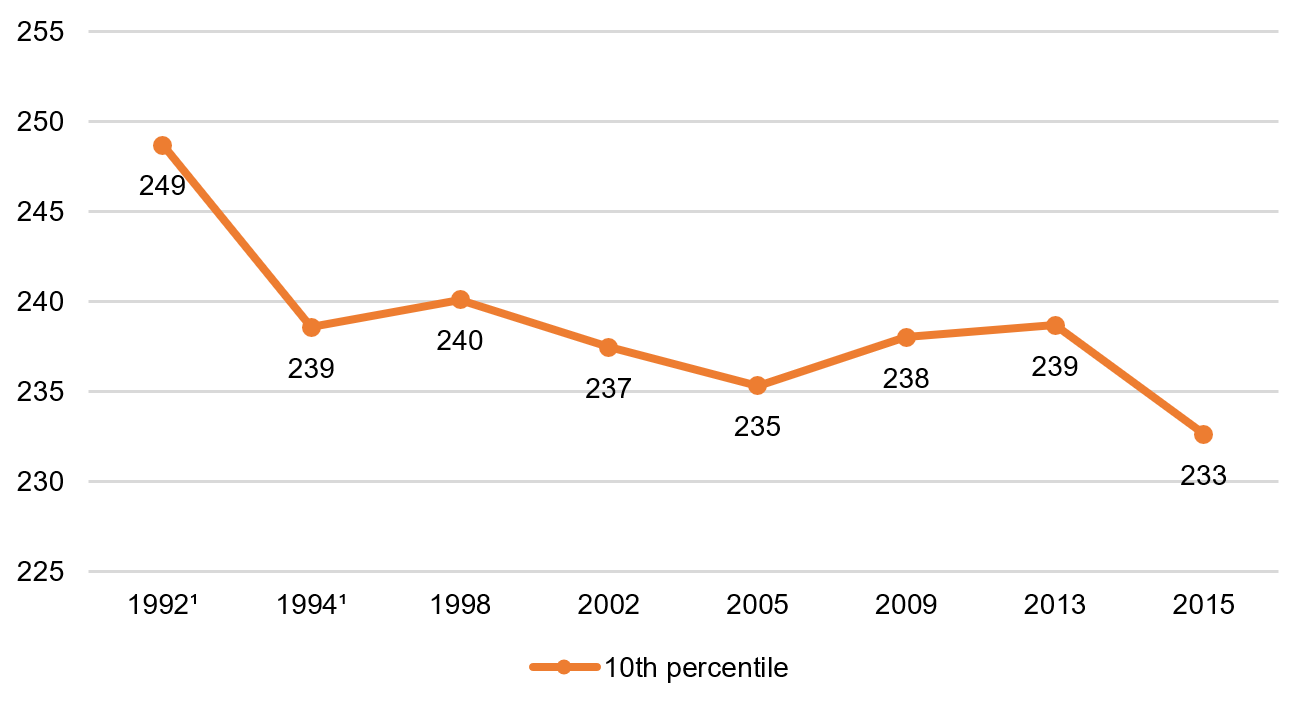

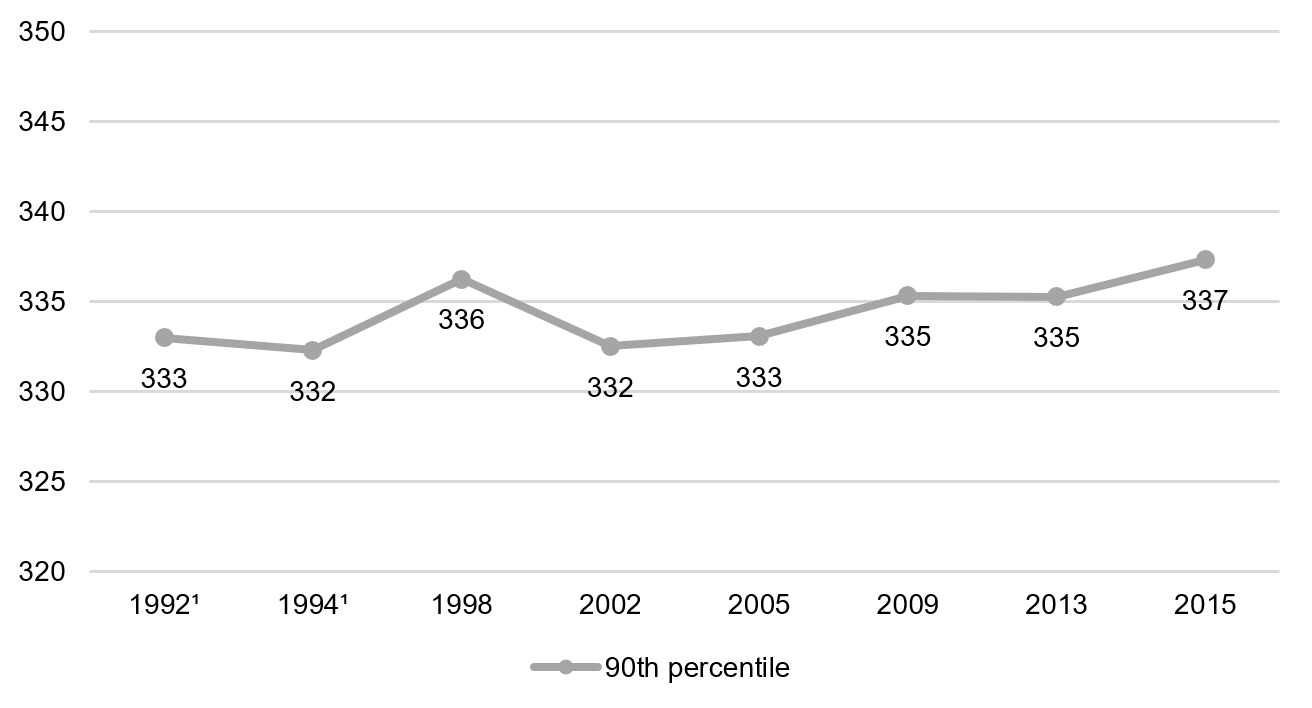

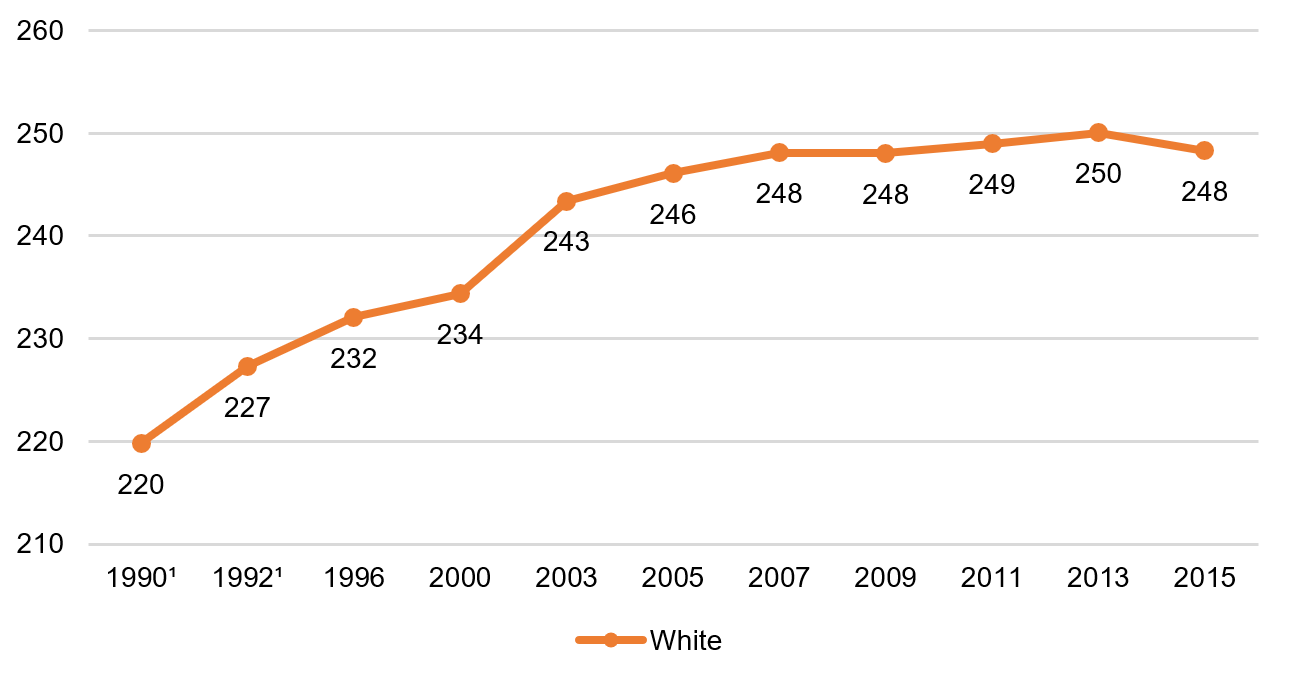

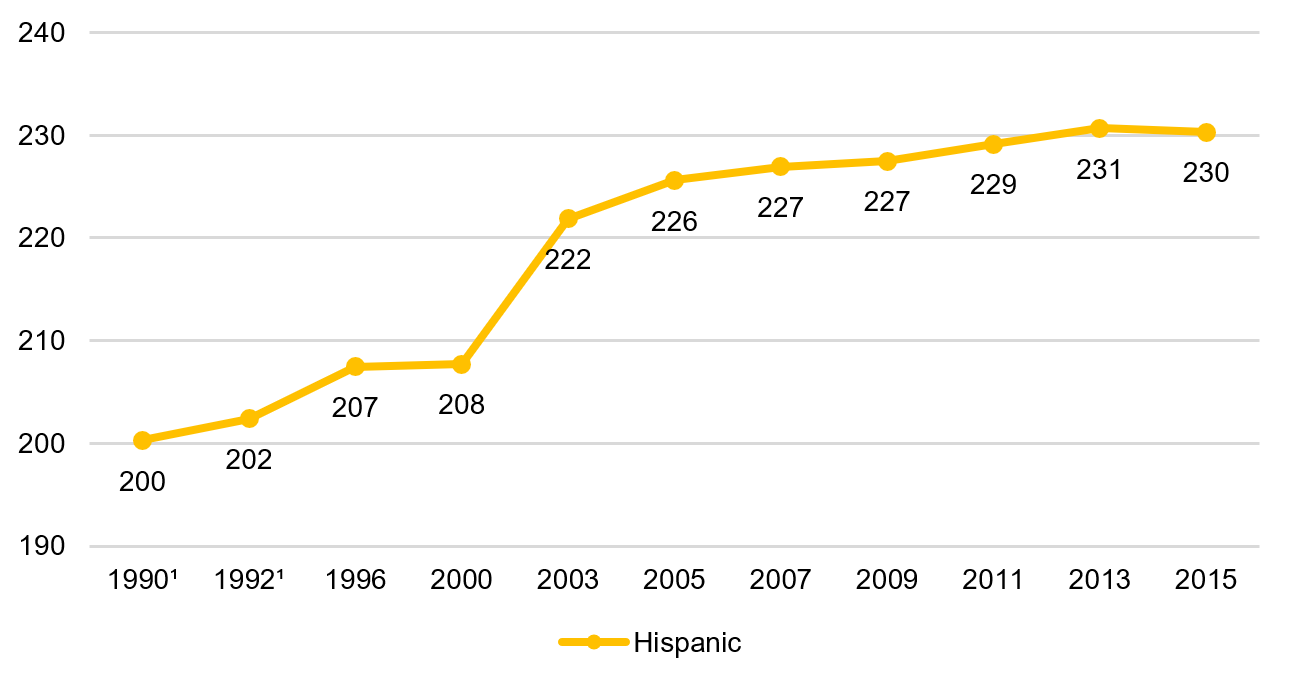

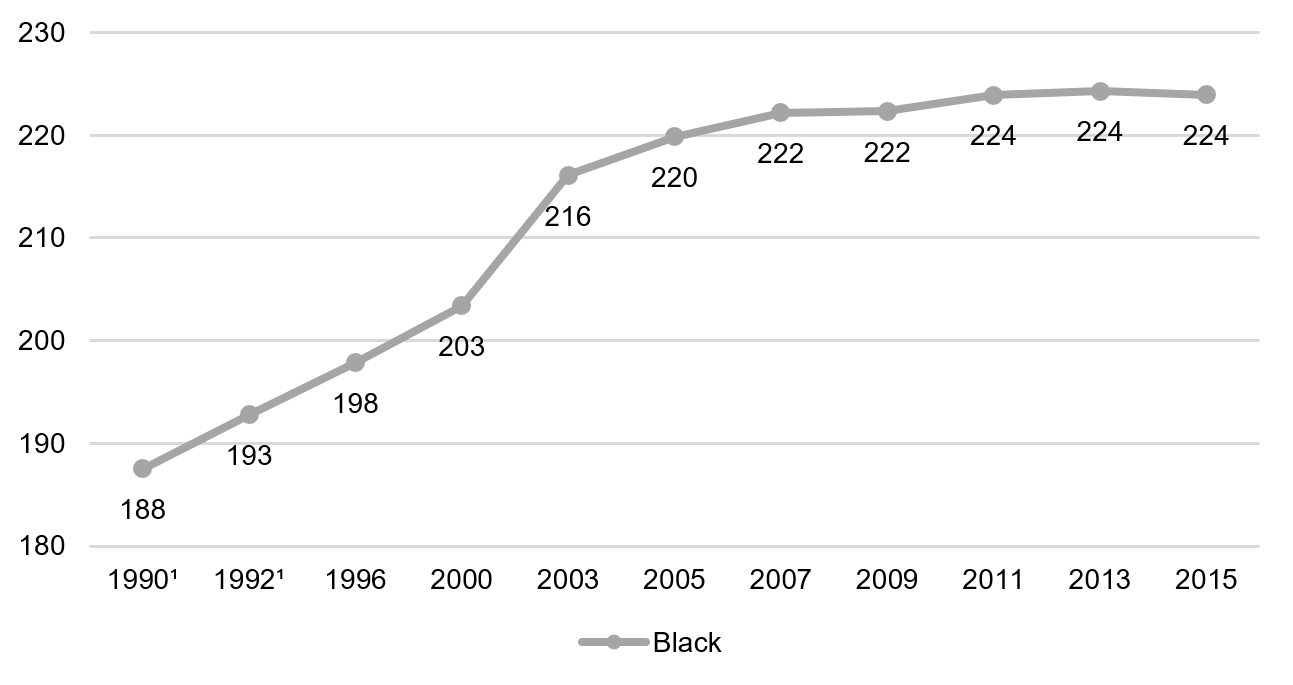

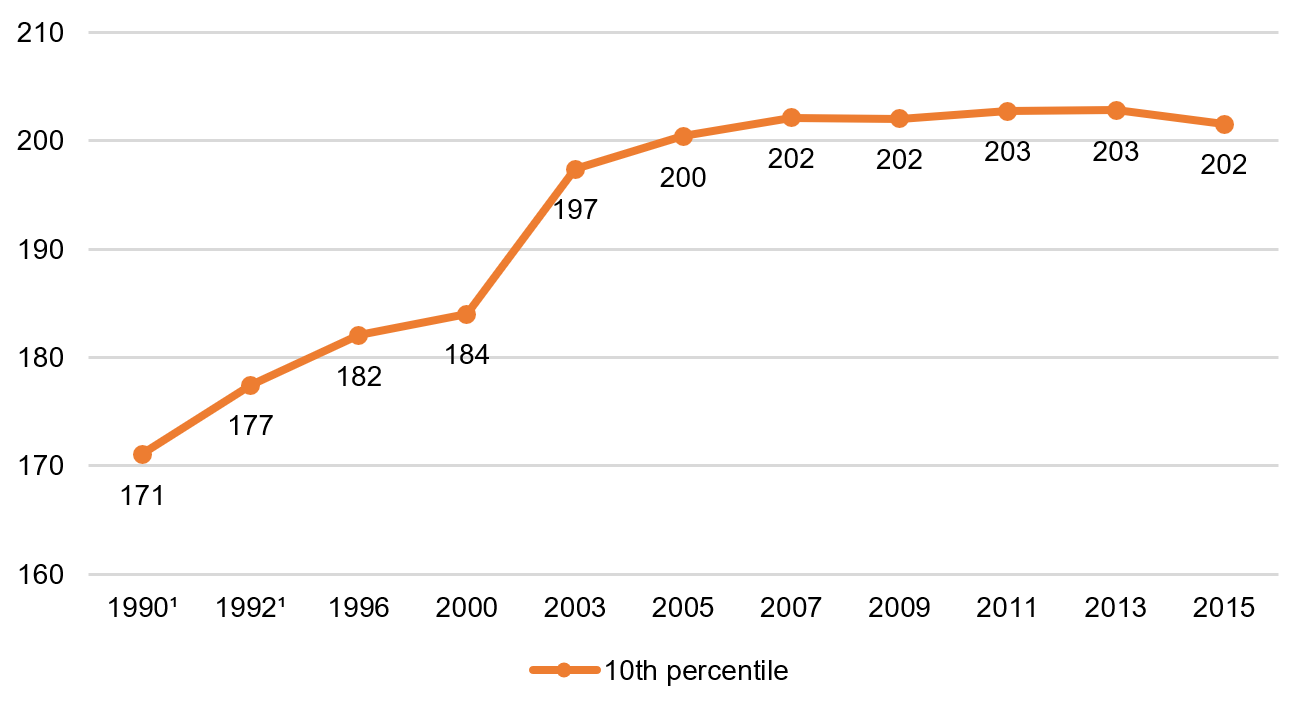

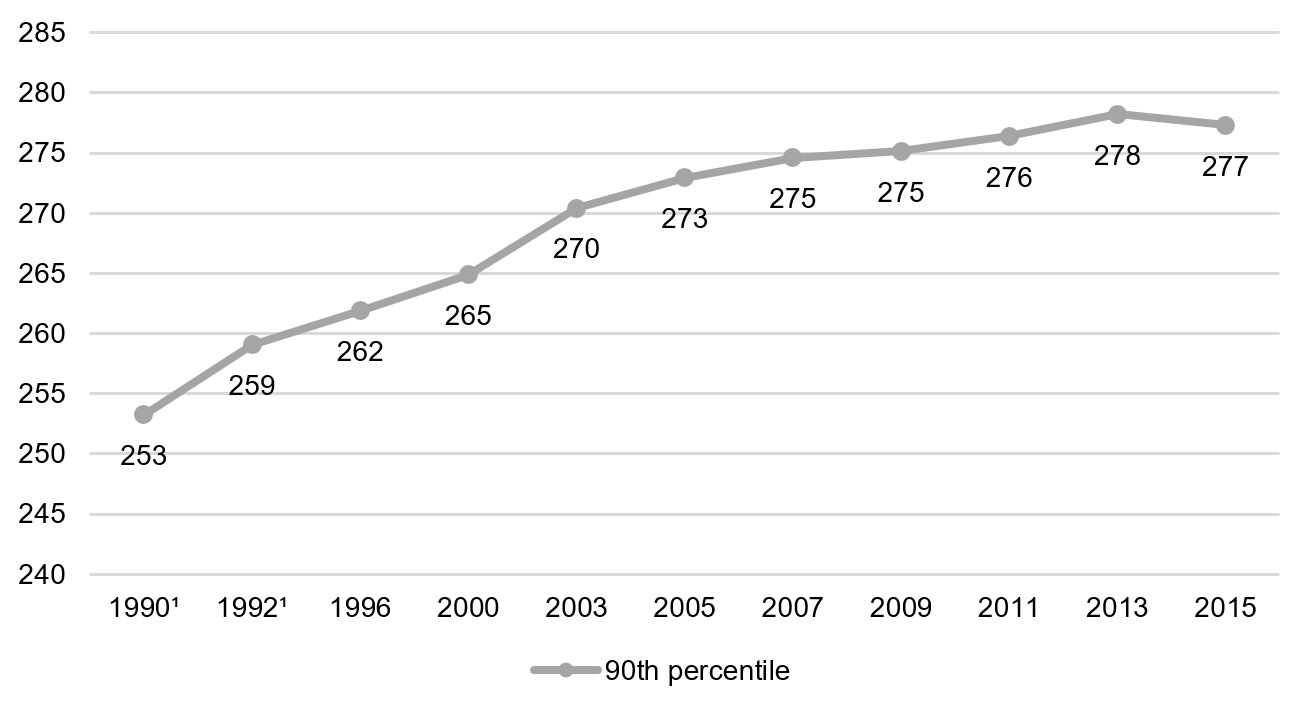

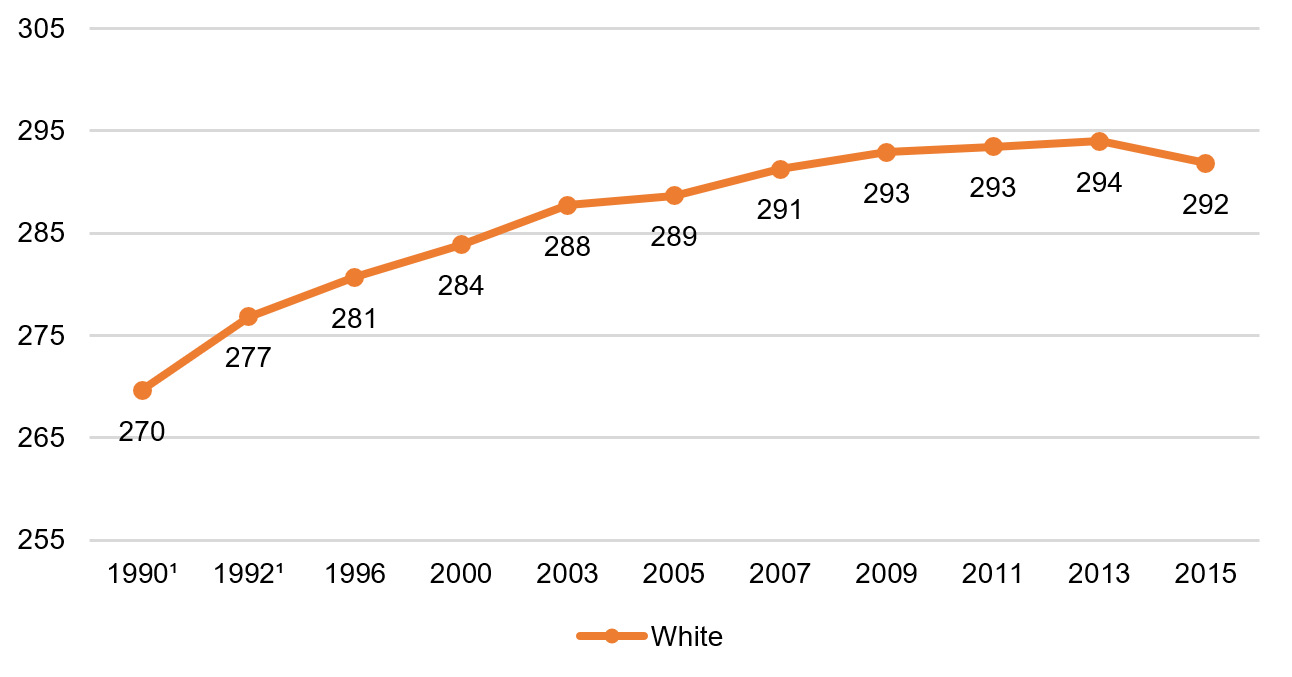

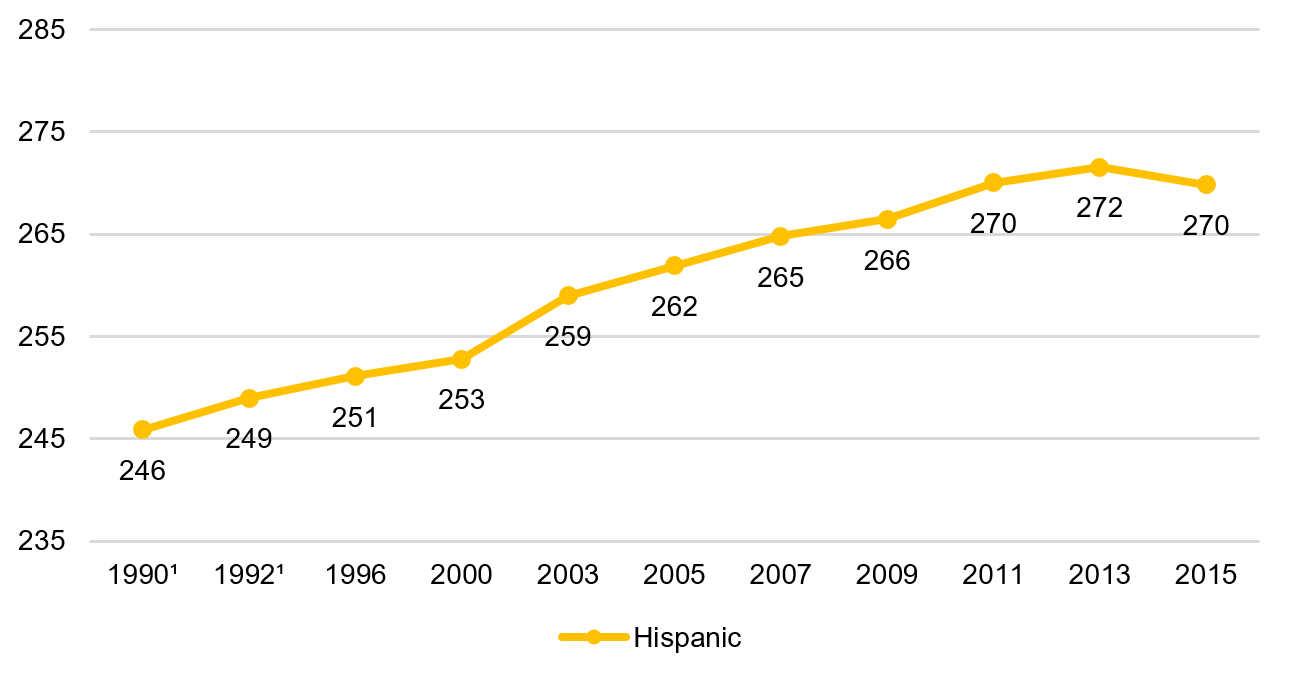

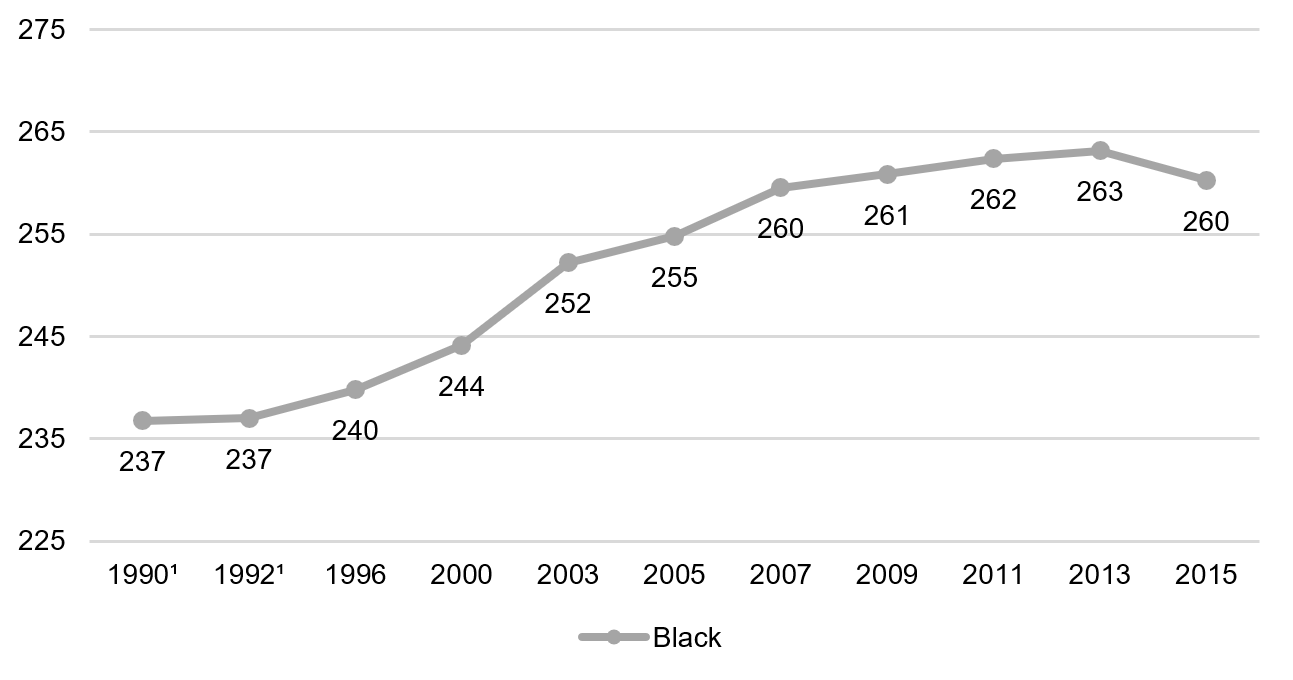

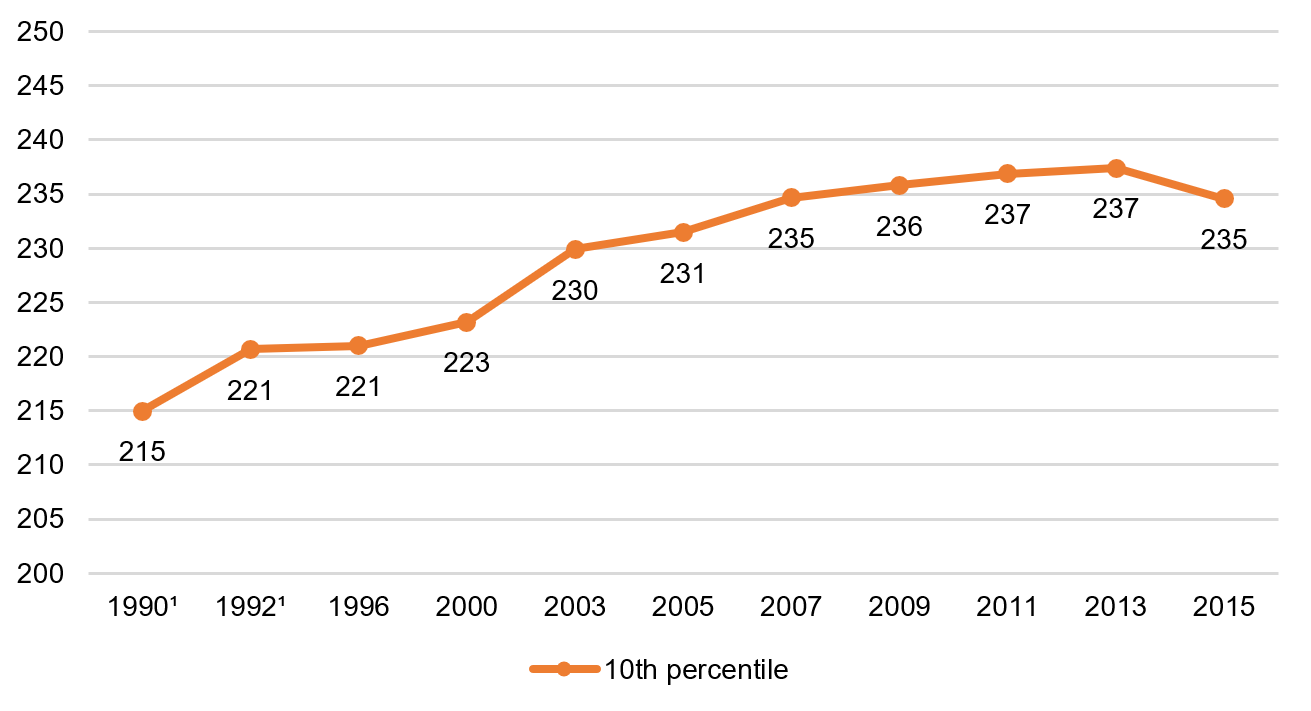

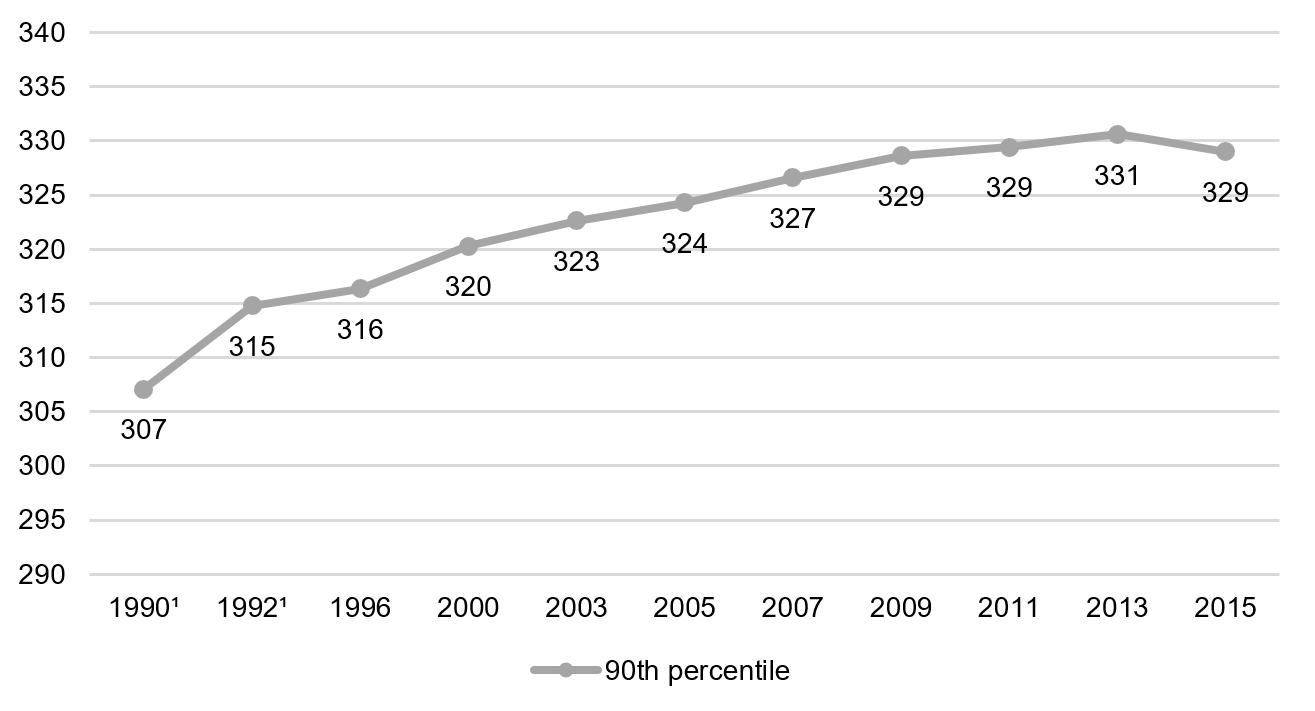

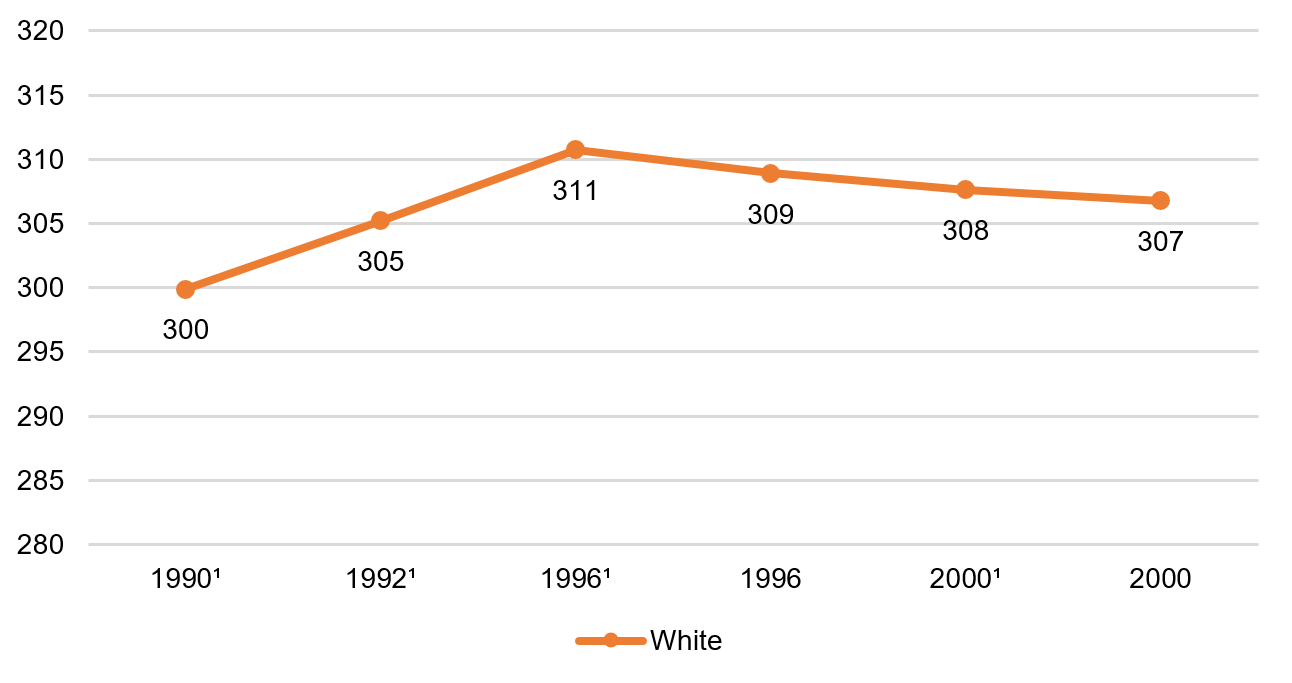

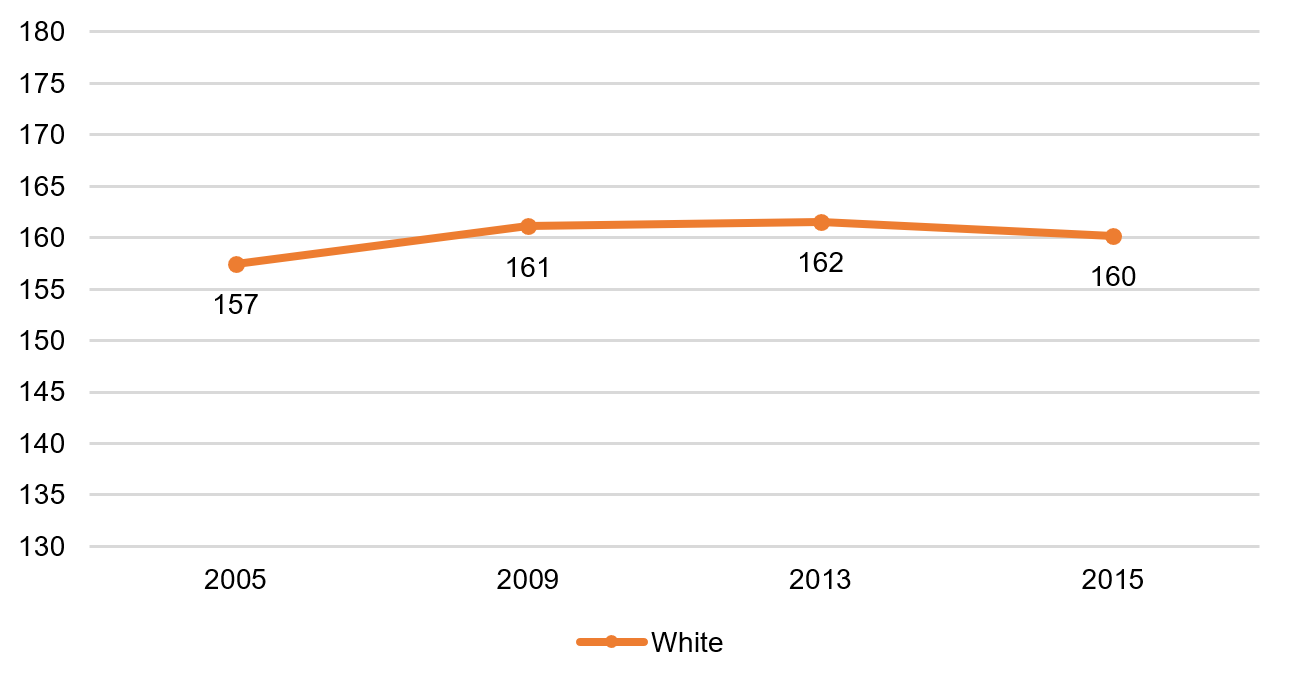

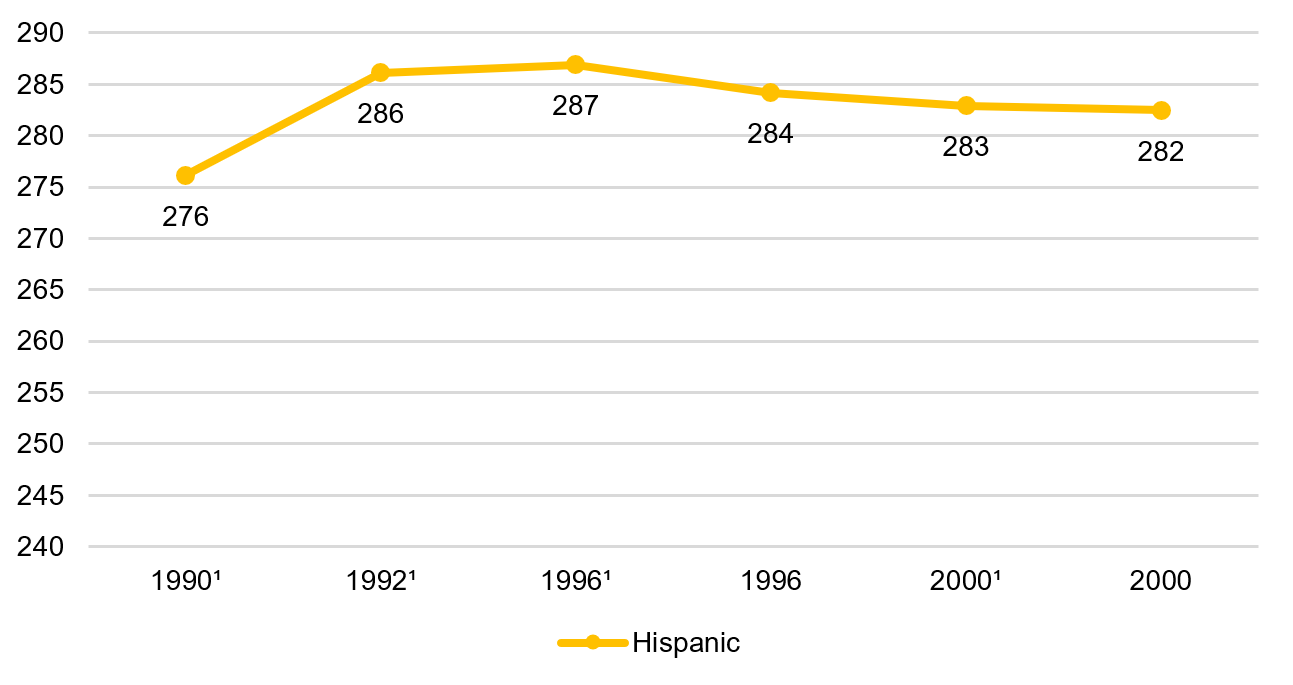

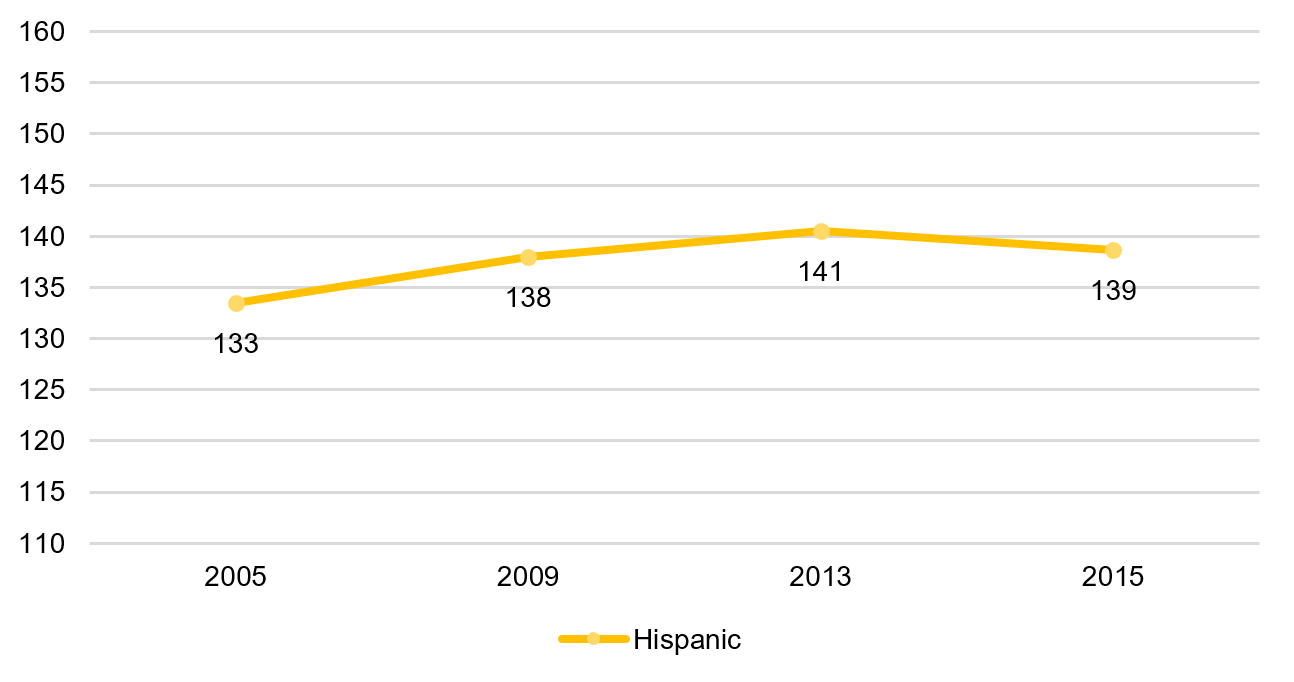

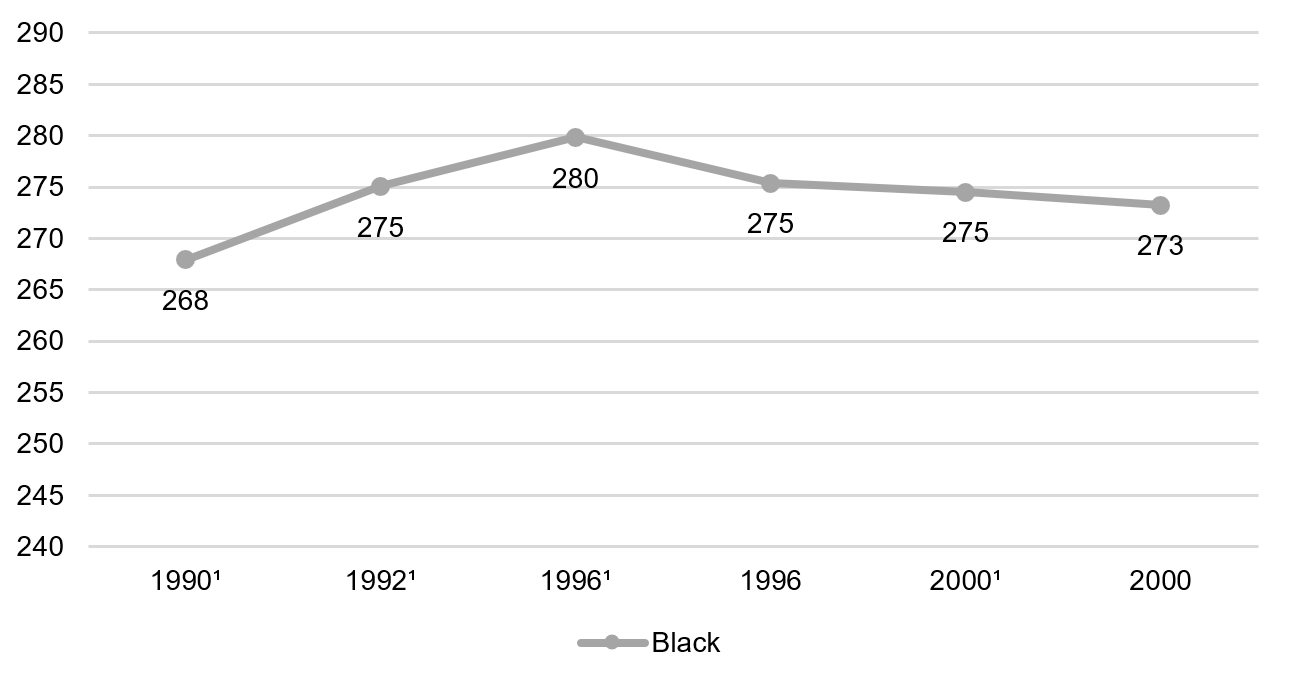

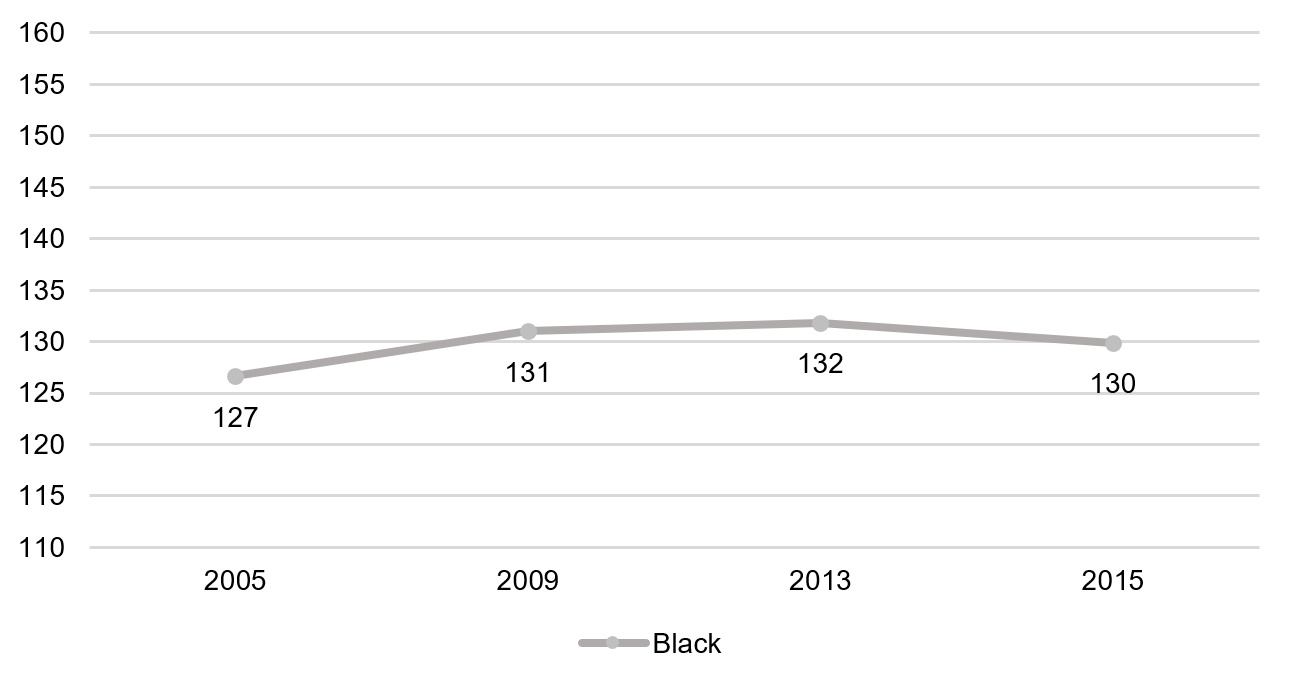

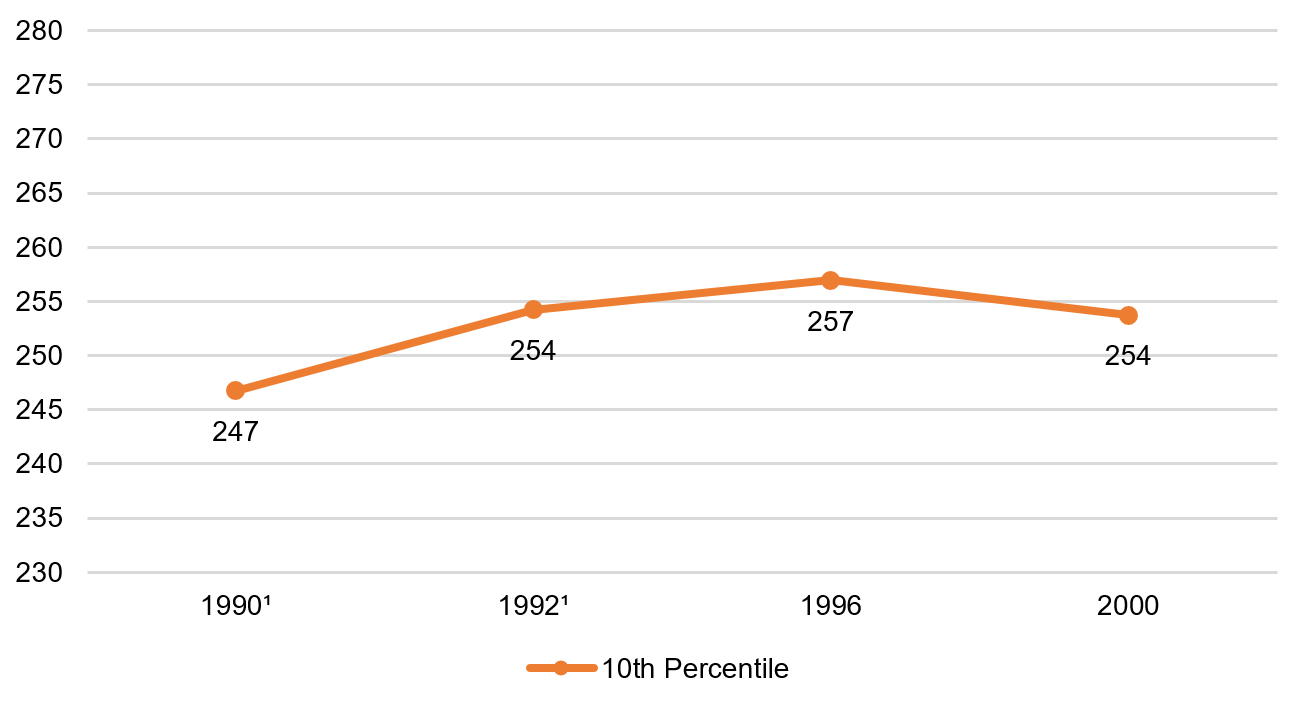

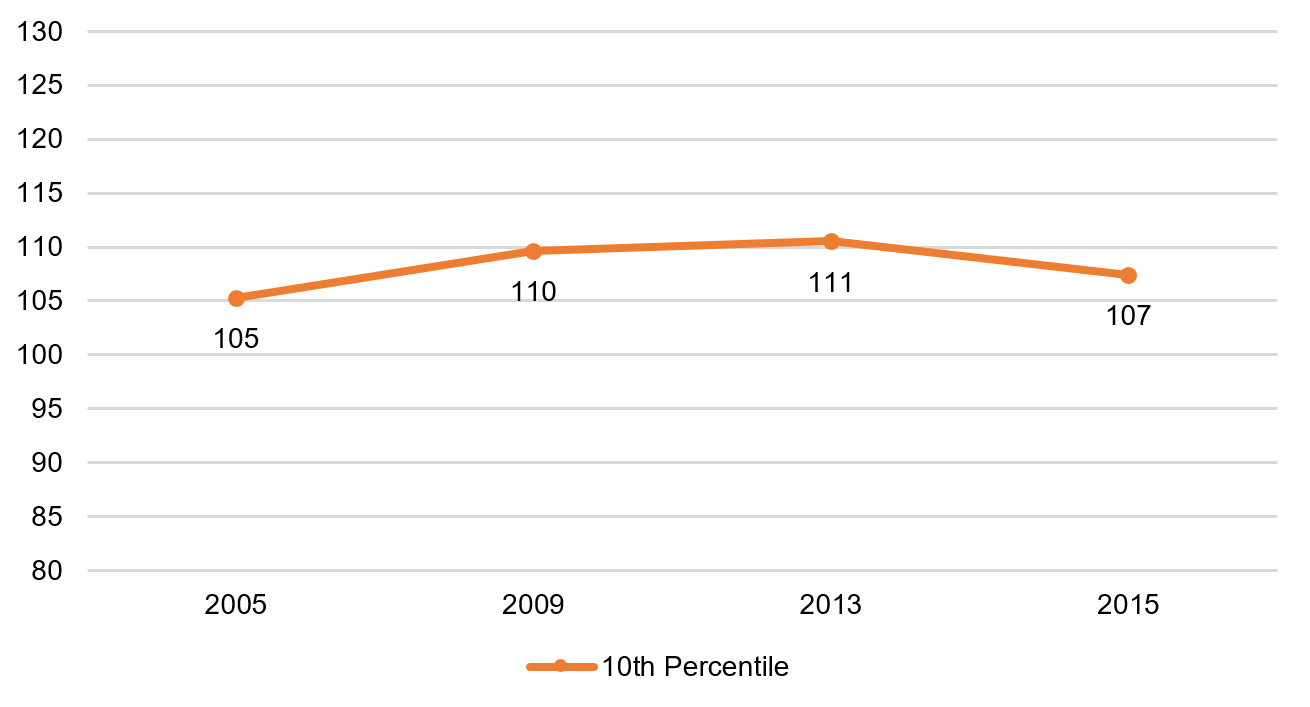

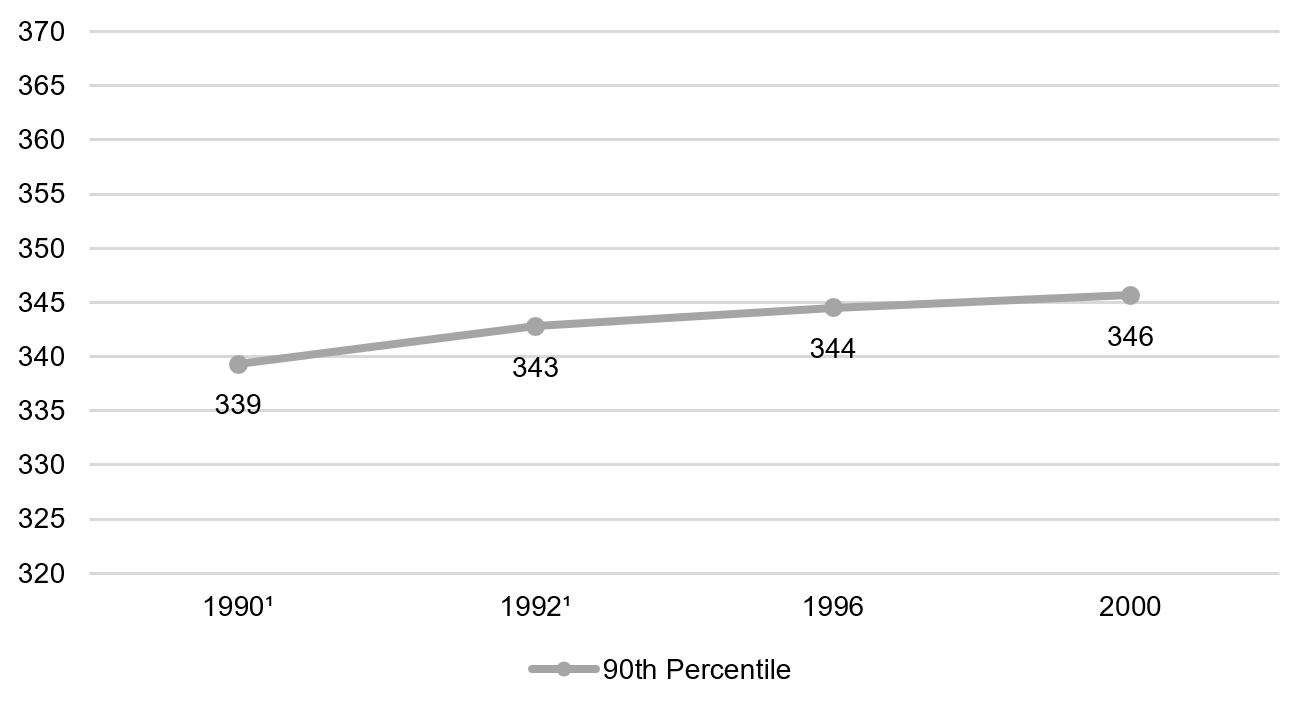

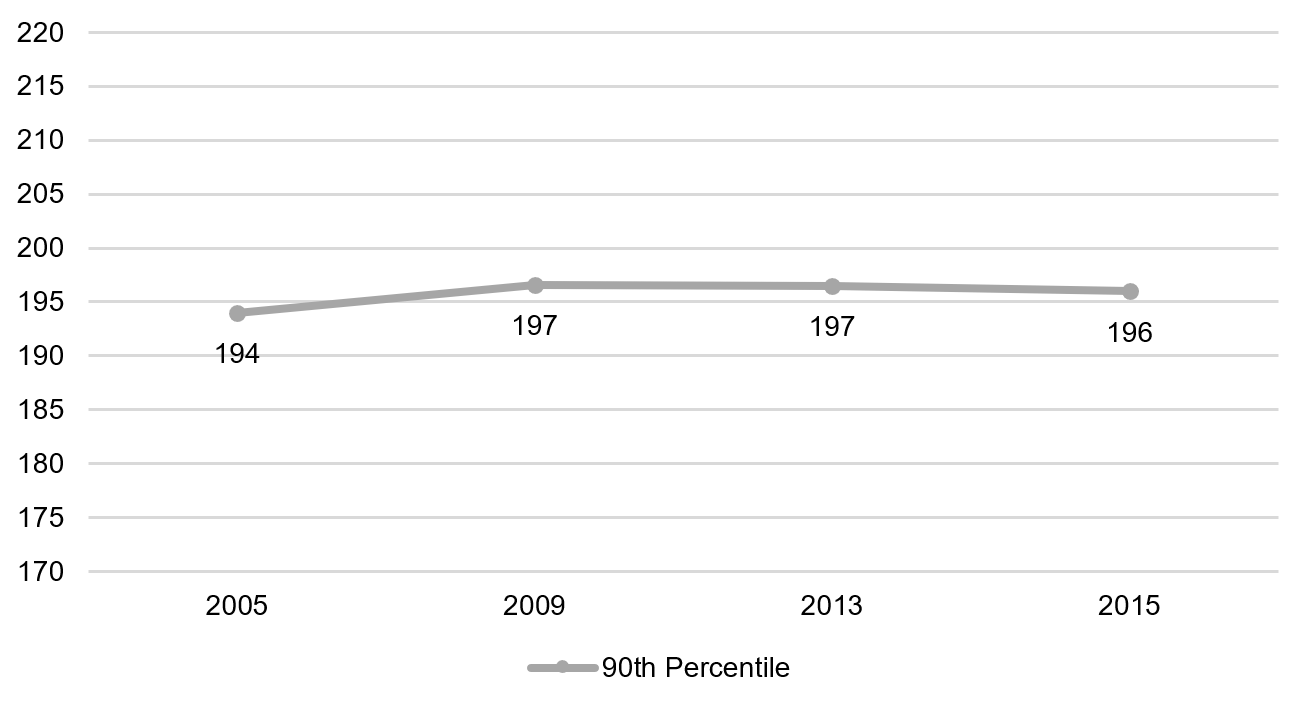

With these principles in mind, let’s see how U.S. students have performed over the past twenty-five years on the “regular” (versus “long term”) NAEP. That’s the one that will soon be updated with 2017 scores.

We relied on the NAEP Data Explorer to generate our charts, and we used NAEP’s national sample, which includes public and private schools. For subgroup data, we used NAEP’s “major reporting group” which, prior to 2002, was based on student-reported information. Since then, however, the Education Department uses school-reported data supplemented with student-reported data. And all of the trend lines are unbroken except for twelfth grade math, which introduced a new framework in 2005 that analyses found made comparisons with earlier results impossible.

Key findings:

Those are our takeaways. Scroll through the pictures below and see if you agree. And keep in mind that not every bump up or down is statistically significant.

Reading

Math

“You can’t handle the truth.” I’m beginning to think there was great wisdom in these five words uttered by Colonel Jessup, the character played by Jack Nicholson in the 1992 film “A Few Good Men.” While he was totally wrong in the context of the film, his words seem quite right when applied to America in 2018. Our politics have become so polarized that people avoid asking all the hard questions about the Parkland shooting, unwilling to accept that even a small part of the truth may not align with their preferred narrative.

The powerful pro-gun lobby, with the NRA as its leader, has done everything in its power to shut down research on gun violence for fear that it may lead to increased gun control. But how can we have an honest debate about gun violence if we can’t even study the issue?

Similarly, since 2013, schools have been under enormous pressure—for good reason—to lower their suspension, expulsion, and student arrest numbers. Broward County was part of the PROMISE program (Preventing Recidivism through Opportunities, Mentoring, Interventions, Supports & Education), which was intended, according to the website, “to safeguard the student from entering the judicial system.” Sounds good to me.

But now we know that school resource officers never arrested Cruz, despite repeated violent behavior. Local outlets like The Sunshine State News and even Jake Tapper of CNN are asking very fair, and much-needed, questions about the possibility that the policy changes around school discipline made it too easy for Cruz to fly under the FBI’s radar, even when he was popping up constantly on the school district’s radar, including for what appear to be committed felonies.

Former school resource officer Robert Martinez claimed that he and others were instructed not to arrest students and that the pressure to keep arrest numbers down meant that even very serious—and violent—offenses were handled in-house instead of being turned over to police.

“We are the laughing stock of the world right now.”

Recently retired @browardsheriff school resource officer speaks out because he says current officers are afraid to. Says there is a shortage of SROs, and pressure not to arrest troubled students like Nikolas Cruz. @wsvn

— Brian Entin (@BrianEntin)

Maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not. But it seems like a no brainer that we should at least find out.

It is undeniable that suspensions and expulsions in the United States disproportionately affect students of color. The same infraction is often handled totally differently based on the demographics of the school as well as the presence—or lack—of law enforcement on campus.

Time and time again we have seen students of color, often poor, get tangled up in the criminal-justice system because a minor infraction at school landed them in handcuffs. In general, students of color are far more likely than their peers to be arrested for disruptive behavior. A student from South Carolina, for example, was ripped from her desk, tossed across the room, and subsequently arrested for defiance. As one Georgia judge described the situation, kids are being prosecuted because they “made an adult mad.” White suburban students make adults mad too but they don’t get arrested for it at school. Add to the arrest the subsequent inability to afford bail or quality counsel and black youth find themselves in the grip of the juvenile justice system.

But have we moved so far into our partisan corners that we refuse to admit that we can go too far in efforts to eliminate arrests that should never happen and end up eliminating ones that should? Do we equate a student who is defiant with one who brings ammunition to school, cyberstalks, and sends threatening messages online? Dear God, I hope not.

I pray I will never personally know the pain the parents of Stoneman Douglas High School now feel and will have to endure for the remainder of their lives. But when, as best as I can, I try to put myself in their position, I would want to know everything that should have been done differently by my elected leaders, the Sheriff’s office, the FBI, and yes, the school department.

While it is tempting to try to identify one sole cause of what happened in Parkland, it is rarely ever that simple. The families of those lost deserve all the answers, not just some. We do not know everything that happened in the lead up to the Parkland shooting; no one does. But one thing seems certain: A number of factors contributed to that tragic outcome—some far worse than others, some more avoidable than others. To pretend the reason is simple or singular is to choose politics over truth, and that is a lousy way to honor the memory of those we lost.

Editor’s note: This essay was original published by Real Clear Education.

Editor's note: This post is a submission to Fordham's 2018 Wonkathon. We asked assorted education policy experts whether our graduation requirements need to change, in light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere. Other entries can be found here.

In light of the graduation scandals in D.C. Public Schools, Maryland, and other places, we have a new chance to ask ourselves an old question: What do we want to do differently?

How do we address the pressure school and district leaders feel to graduate kids that aren’t meeting requirements? (Finger-wagging and firing people certainly isn’t a complete solution.) And, most importantly, what do we want high school graduation to mean anyway?

This last question is essential if we’re going to get at what graduation requirements should be, so let me start there.

Here’s a multiple-choice question to kick it off: What does a high school diploma signify to you?

There’s no wrong answer here. The point is we don’t all agree on what a diploma actually means (Twitter agrees with me), or even what it should mean. Many of us want it to mean “all of the above.” We want it to signal that students have the academic chops to move on to college or the technical skills to start down a career path. Some are even proposing we raise the standards for (and the integrity of) high school graduation by denying diplomas to those who can’t pass grade-level tests in required subjects.

For many others, “earning a diploma” means little more than that students completed a required program they probably found irrelevant, uninspiring, and monotonous. In one Twitter response, Robert Pondiscio took it a step lower and suggested receiving a diploma merely means that a student is at or near the age of eighteen (#SadButTrue, @rpondiscio, particularly when school leaders game the system.)

The problem is that each of these achievement goals—completion, college-ready, and skill-certified—are too different from each other to have one diploma representing each level. As such, the high school diploma ends up taking on the meaning of the lowest common denominator: completion.

We should differentiate diplomas

If our purpose in measuring graduation rates is to help as many students as possible become as successful as possible in adulthood, then continuing a system in which nearly everyone essentially gets a certificate of completion isn’t going to cut it. It’s true that there are other signals for college readiness (e.g., ACT/SAT scores, GPA, college application essays, etc.), but graduation should be one that joins with these other indicators to give people a more complete picture.

Denying diplomas to students who pass their classes (even if barely) and stick it out to the end also falls short of our goal. In that case, students who finish are treated the same as dropouts, which can lead to an undeserved feeling of defeat and limited opportunities because they don’t have anything to show for their effort.

By offering different diplomas depending on what the high school student has actually accomplished, we can bring honesty and clarity to graduation practices, and at the same time help children become as successful as they can be.

These designations should be simple and easy to interpret: 1. Finisher; 2. Academically Ready; 3. Skill Certified.

Finisher

Everybody who meets the minimum standard gets a diploma. This isn’t too far from what we have now, it’s just that nobody actually goes around and says “your kid’s diploma is essentially just a certificate of completion. It doesn’t certify that he actually learned anything.” Nobody tells you that all it signifies is that he or she showed up for enough of their classes and, one way or another, passed them.

Though some may dismiss this idea as lowering the bar or devaluing the diploma, I would argue that it only lowers the bar if this is the only bar. Besides, it’s actually not lowering any bar; it’s simply acknowledging how low it already is. I would also contend that there’s value in just showing up, barely passing, and sticking it out to the end. James Heckman, acclaimed researcher at the University of Chicago, proved as much. Students who stick it out and pass, even if they struggle, deserve something that recognizes that work—something that distinguishes them from the dropout. The standards for receiving that diploma can essentially stay the same as they are in many states: Don’t miss too many days of school, pass your classes, and make up work if needed.

Academically Ready

This designation can be added to the base-level diploma similar to the way an honors designation is added in many existing systems. But the difference is that it will be based on students meeting proficiency levels on academic standards. In other words, they are actually competent in the required areas. Earning a high GPA and getting an “honors” designation is pretty subjective. Depending on the class, teacher, school, or district, you can have a lot of variation in terms of getting those grades. Scoring proficient on a standardized test is by no means a perfect measure, but it at least gives consistency across a state and thereby is a more meaningful measure of academic achievement.

Skill Certified

Kids who choose the career and technical education route can get the base-level diploma with an added CTE stamp for achieving certain technical skills in health-care, construction, programming, culinary arts, or whatever they choose. If states haven’t already defined high school certification levels, they can easily do so. Each specific area of certification can be noted on or with their diploma.

Acknowledging differences in a diploma will take some of the pressure off school leaders to cheat. It signals that, although we want all students to achieve at high levels academically or technically, there’s room for the reality that all kids won’t get there right away, and that there is value in getting kids across the finish line with integrity.

Make it meaningful

New Hampshire and Louisiana have started awarding differentiated diplomas in ways similar to what I’ve suggested. New York has been differentiating for decades. But they have so many designations, many of which are way too wonky, that most people don’t understand the difference or even bother keeping track. If the system for awarding diplomas is too complex, it loses meaning for those intended to benefit from it. As parents and students, it’s easy to grasp three levels and aim for your goal. But having a dozen different diplomas, like they do in the Empire state, muddles the meaning of each diploma and weakens accountability.

As parents, we want our children to move out someday, establish their own families, and be able to take care of themselves and others. As a society, we want people who work (adding to the economy and tax base), create, solve problems, volunteer, vote, inspire, build our nation, and serve the world. Getting a diploma doesn’t guarantee any of that, but if we are honest about how we award them and clear about what a diploma means, graduating high school can be an indicator of how well we’re reaching those goals.

On this week’s podcast, Aimee Rogstad Guidera, president and CEO of the Data Quality Campaign, joins Alyssa Schwenk and Brandon Wright to discuss what ed reform’s decades of progress portend for the future. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines career-tech’s effect on human capital accumulation.

Shaun M. Dougherty, “The Effect of Career and Technical Education on Human Capital Accumulation: Causal Evidence from Massachusetts,” Education Finance and Policy (forthcoming).

Liberal arts degrees get a bad rap. They’ve been called worthless and inferior, and some have even suggested that it may be wiser to get no college degree at all. Yet do not fear, all you liberal arts graduates, there’s welcome news for you in Mark Schneider’s and Matthew Sigelman’s latest report, Saving the Liberal Arts: Making the Bachelor’s Degree a Better Path to Labor Market Success. The duo from the American Institutes for Research examines whether students graduating with liberal arts degrees are getting a good return on their investment, and how they might maximize those degrees by incorporating other skills.

They use data from Burning Glass Technologies, which, according to their website, is an analytics software company that is “powered by the world’s largest and most sophisticated database of jobs and talent, [delivering] real-time data and breakthrough planning tools that inform careers, define academic programs, and shape workforces.” The BGT database has over 150 million unique job postings dating back to 2007, and over 78 million resumes. Their technology extracts information from roughly 50,000 online job boards, newspapers, and employer websites daily. They claim to capture, at minimum, 80–90 percent of job postings that organizations post online. BGT then codes the data to extract granular information from postings about labor market trends and new and emerging skills needed for various jobs, then supplements those data with information from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Specifically for this report, job posting data are pulled for a twelve-month period from December 2016 to November 2017.

Using data from a supplemental source, Schneider and Sigelman first find that the median earnings by age thirty for those in liberal arts and the humanities is $36,683, which is lower than almost a dozen other major fields of study. They also find that, from 2007–16, there’s been a 4 percent decline in the number of bachelor’s degrees conferred in liberal arts and the humanities; contrast that to the 55 percent increase in biology and life sciences. Next the AIR researchers identify a set of occupations that represent “entry-level opportunities” for all college graduates (meaning you need a college degree, including associates, and less than five years of experience), and then take out jobs that require advanced and specialized degrees. They are left with 1.4 million unique entry-level postings over the last year for which liberal arts degree holders could qualify. The researchers then group related occupations with similar skills together into ten career clusters (examples below) because they presumably “offer opportunities to build transferable skills, and provide sustainable employment and advancement opportunities.”

Schneider and Sigelman find that, relative to the highest proportion of entry level openings, the top five industries are business administration, data analysis/data management, human resources, IT and networking, and sales. Yet when one looks at the share of entry-level jobs filled by liberal arts graduates, data show that these candidates fill 83 percent of the openings in “media and communication”—jobs like writers, editors and reporters. In the other two industries most likely to be filled by liberal arts graduates, they fill 54 percent of design positions (jobs like graphic and industrial designers) and 50 percent of openings in and marketing and PR. Yet, according to BLS, these are also the two industries that have the least projected amount of employment growth. The AIR analysts find that sectors like business administration, data analysis and management, and programming and software development have higher projected employment growth, but smaller shares of entry level jobs held by liberal arts graduates.

Finally, Schneider and Sigelman identify workers with liberal arts degrees who started in one career cluster, and then calculate the percentage who ended up in another five years later, as well as their likelihood of doing so. They find that many career clusters open to liberal arts grads offer early- and mid-career salaries comparable to those attainable by all bachelor’s graduates and even STEM grads. For instance, the average STEM graduate has an expected five-year salary of $76,500, which is similar to what marketing and PR grads make at five years—50 percent of whom are liberal arts grads. The report includes example “pathways” for liberal arts graduates relative to career clusters that award them with progressively more responsibility and higher pay. The idea is that these graduates can propel themselves faster and further if they attain particular skills (listed in the report) and experience in different clusters.

The bottom line is that liberal arts degree holders are not doomed. Like everyone else, they can make the most of their job prospects if they attain the right combination of skills, talents, and knowledge along the way.

SOURCE: Mark Schneider and Matthew Sigelman, “Saving the Liberal Arts: Making the Bachelor’s Degree a Better Path to Labor Market Success,” American Enterprise Institute (February 2018).

A January study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) examines academic “resilience”—the capacity of disadvantaged students to succeed despite adverse circumstances—in more than seventy education systems that participated in the 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2015 iterations of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Authors sought to determine the role that school environment and academic resources play in resiliency, and examined differences in rates of resilience in participating countries over time.

The study defines “resilient students” as those in the lowest socioeconomic quartile in their own country who achieve at or above Level 3 (out of 6) on all of PISA’s three subjects—reading, math, and science. “Level 3 corresponds, in each subject, to the highest level achieved by at least 50 percent of students across OECD countries on average,” explain the authors. They characterized school environment using the OECD’s survey data on truancy—how many students skipped a whole day in the last two weeks—and the frequency of classroom disruptions—insubordination, excess noise, etc. And the study measured school resources with an index comprising three variables: the availability of computers per student, the number of extracurricular activities offered, and the average class size of each school.

The study’s main finding was that, after controlling for the socioeconomic status of schools’ student bodies, school environment and academic resources explain, on average, about one-third of the variation in the number of resilient students between schools in a given country. But the effect of these variables differed between nations. In all but nine countries, for example, school environment has a statistically significant, positively associated effect on resilience. But for extracurricular activities—a component of researchers’ academic resources index—that was only true in a dozen nations. Moreover, a school’s environment was far more significant than its resources. “Attending orderly classes in which students can focus and teachers provide well-paced instruction is beneficial for all students, but particularly so for the most vulnerable students,” concluded the authors. And “resilience is only weakly related to the amount of human and material resources.”

The study also found that several countries, including Germany, Israel, Japan, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain, saw their proportion of resilient students increase over time. But it dropped in many other places, like Finland, South Korea, New Zealand, Austria, Canada, Hungary, Iceland, Sweden, and Slovakia. Based on the main finding, this likely has something to do with changes in environment and resources. But the authors also found that student- and school-level socioeconomic status has a significant effect on rates of resiliency (hence SES being controlled for), so fluctuations in countries’ economies probably also play a sizable role.

The study does, however, have some limitations. Most importantly, all of these data are based on answers given by students, teachers, and schools on questionnaires that OECD includes as part of its PISA administration. It also doesn’t look at student growth over time.

Nevertheless, with the ed reform community perpetually abuzz about achievement gaps and discipline policies, this study provides valuable insight into contributing factors. It suggests that less disruptive classrooms may boost disadvantaged students’ achievement, and provides some evidence that school resources can help too.

SOURCE: Agasisti, T., et al. "Academic resilience: What schools and countries do to help disadvantaged students succeed in PISA", OECD Education Working Papers. (January 2018).