Author’s Update, August 5, 2022: Analysis of NAEP demographic data shows that retaining students was in fact not a major contributor to Mississippi’s improved fourth grade NAEP results in the last few years—at least not the way this article suggested. The average age of Mississippi’s fourth grade test-takers was almost identical in 2002 and 2017; increased retention should have raised the age. That suggests that Mississippi has long had a higher retention rate than most states, perhaps making its reading retention policy less controversial than in other places. For further thoughts on how the retention policy has impacted Mississippi’s NAEP results, see my related Fordham Institute post from January 2022: “Student retention and third-grade reading: It’s about the adults.”

One of the bright spots in an otherwise dreary 2019 NAEP report is Mississippi. A long-time cellar dweller in the NAEP rankings, Mississippi students have risen faster than anyone since 2013, particularly for fourth graders. In fourth grade reading results, Mississippi boosted its ranking from forty-ninth in 2013 to twenty-ninth in 2019; in math, they zoomed from fiftieth to twenty-third. Adjusted for demographics, Mississippi now ranks near the top in fourth grade reading and math according to the Urban Institute’s America’s Gradebook report.

So how have they done it? Education commentators have pointed to several possible causes: roll-out of early literacy programs and professional development (Cowen & Forte), faithful implementation of Common Core standards (Petrilli), and focus on the “science of reading” (State Superintendent Carey Wright).

But one key part of Mississippi’s formula has gotten less coverage: holding back low-performing students. In response to the legislature’s 2013 Literacy Based Promotion Act (LBPA), Mississippi schools retain a higher percentage of K–3 students than any other state. (Mississippi-based Bracey Harris of The Hechinger Report is one education writer who has reported on this topic.)

The LBPA created a “third grade gate,” making success on the reading exit exam a requirement for fourth grade promotion. This isn’t a new idea of course. Florida is widely credited with starting the trend in 2003, and now sixteen states plus the District of Columbia have a reading proficiency requirement to pass into fourth grade.

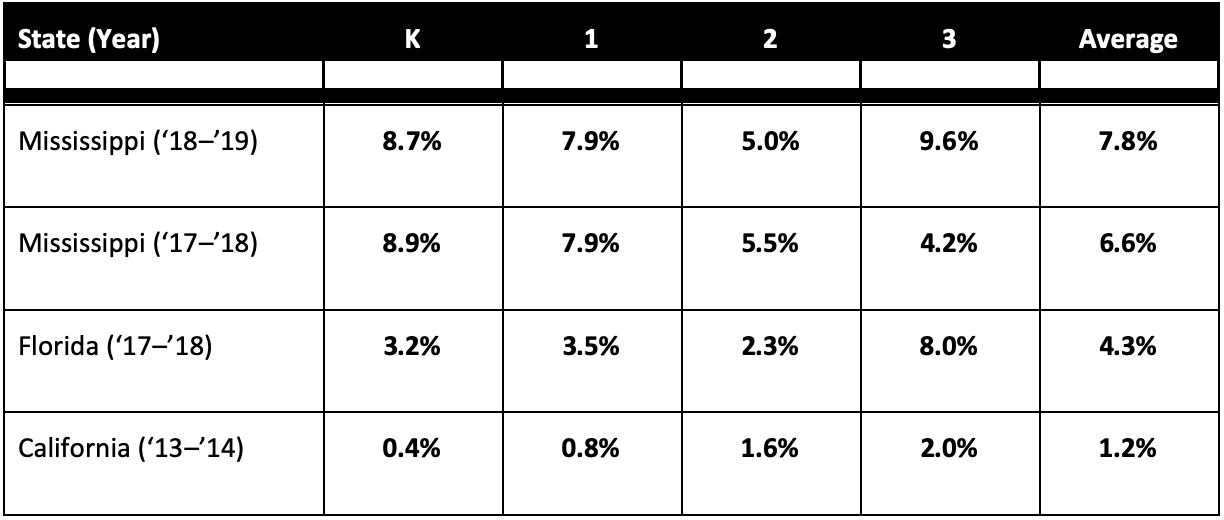

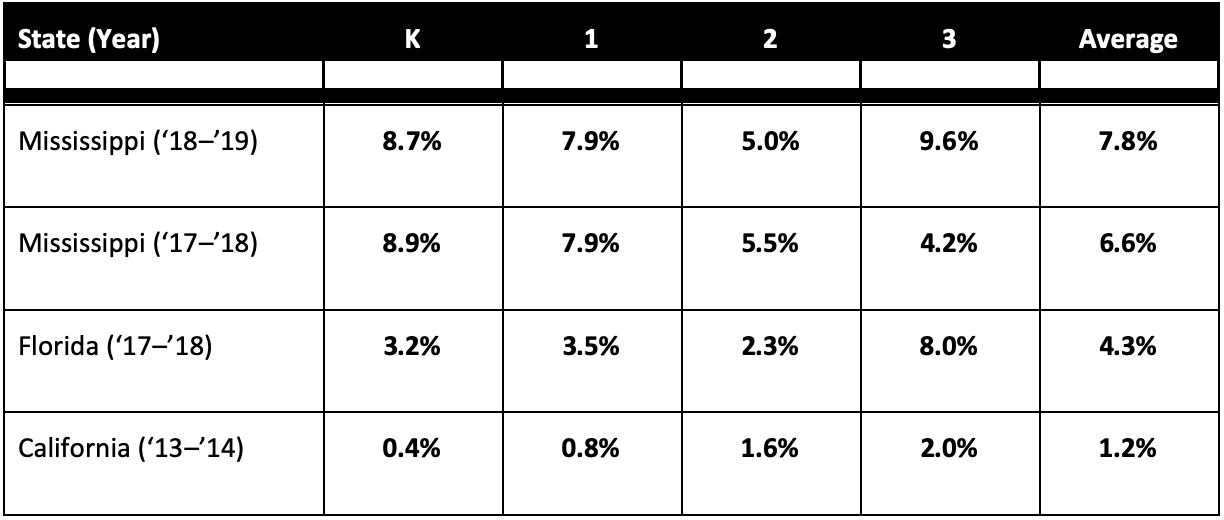

But Mississippi has taken the concept further than others, with a retention rate higher than any other state. In 2018–19, according to state department of education reports, 8 percent of all Mississippi K–3 students were held back (up from 6.6 percent the prior year). This implies that over the four grades, as many as 32 percent of all Mississippi students are held back; a more reasonable estimate is closer to 20 to 25 percent, allowing for some to be held back twice. (Mississippi's Department of Education does not report how many students are retained more than once.)

Table 1: Student retention rate for early grades, selected states

Sources: State reports, U.S. Department. of Education CRDC reports

These retention levels are much higher than other states. The closest are Oklahoma at 6 percent and Alabama at 5 percent. Florida, probably the most well-known example, today holds back 4 percent of its K–3 students, including 8 percent of third graders. When it first enacted its retention policy in 2003–04, Florida’s third grade retention rose as high as 14 percent before steadily declining; it has risen again in recent years. The average for all states is about 3 percent; many states have retention rates of 2 percent or less.

Among the flurry of literacy initiatives in Mississippi, how important is retention to its NAEP results? It’s hard to know for sure, especially without student-level data, but simple modeling suggests it may be a significant factor. Retained students are by definition the lowest performing readers, scoring in the bottom category of Mississippi’s third grade exam. As part of the LBPA, after being held back, they receive a variety of supports, including “intensive reading intervention” and being assigned to a high-performing teacher. Assuming that those policies improve their achievement, they should certainly score better once reaching fourth grade than they otherwise would have.

So is Mississippi’s lesson for educators that they should increase student retention? The traditional view of retaining students is strongly negative. In 2004, school psychology researcher Shane Jimerson famously labeled it “educational malpractice.” According to Stanford researcher Linda Darling-Hammond (now President of the California State Board of Education), “The findings are about as consistent as any findings are in education research: the use of [retention based on] testing is counterproductive, it does not improve achievement over the long run, but it does dramatically increase dropout rates.”

More recently, Martin West and others, looking at the results from Florida’s 2003 retention policy, have taken a more positive view of the impact of early-grade retention, like that practiced by Mississippi. They report that third-grade retention increases high school grade point average and leads to fewer remedial courses, though it does not increase graduation rates (or lower them). With the first Florida cohorts now in early adulthood, we may get a better view of retention’s long-term impact. While some have criticized Florida’s past NAEP score gains as “dubious” and “highly misleading” due to its retention policy, others claim they represent “genuine progress.”

In the meantime, Mississippi isn’t waiting. Buoyed by the perceived success of the 2013 standards, last year the legislature raised the third-grade exit bar even higher, leading to 14 percent of the state’s third-graders failing the test, and 10 percent being ultimately retained (in some counties, up to 45 percent failed and 40 percent were retained). While the long-term effects are uncertain, a very likely outcome will be continued growth in the NAEP fourth grade results, as the lowest performing students get an added year of instruction before the test.