This summer, President Trump signed the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act into law. The legislation, often referred to as Perkins V, is the long-awaited reauthorization of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006. It governs how states implement and expand access to career and technical education (CTE) programs and provides over a billion dollars in federal funding.

Perkins V included a variety of changes and additions to previous law. (Check out this brief from the Alliance for Excellent Education for a detailed overview.) These changes include new requirements regarding what must be included in state plans submitted to the feds for approval. Last week, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education released for public comment its first official guidance on state plans. The public comment window closes on December 24, and finalized guidance will likely be released after the start of 2019.

Within his introduction to the guidance, Assistant Secretary Scott Stump shared his hope that states would use implementation of the new law as an opportunity to “rethink” CTE. He offered a variety of suggestions for doing so, including a call for states to examine “how to make work-based learning, including ‘earn and learn’ programs such as apprenticeships, be the rule and not the exception.”

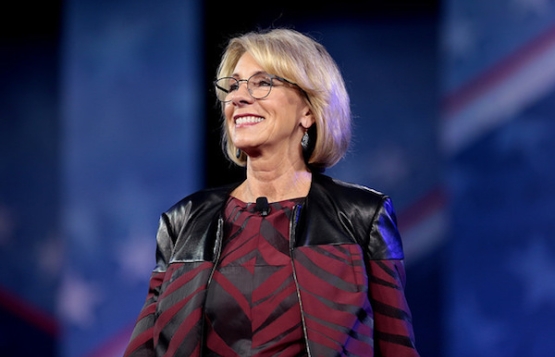

This suggestion should come as no surprise. Secretary DeVos has expressed her admiration of the apprenticeship system in Switzerland, and the president signed an executive order for worker training that includes a focus on expanding apprenticeship programs. The apprenticeship model and CTE in general enjoy broadly bipartisan support. And most importantly, apprenticeships have value: A 2012 Mathematica study found that those who participated in registered apprenticeships had substantially higher earnings than nonparticipants, and that the social benefits were much larger than the costs.

But touting apprenticeships from the bully pulpit is different than creating, funding, and implementing high quality apprenticeship programs at the state and local level. And apprenticeships aren’t the only form of work-based learning out there. Perkins V defines work-based learning as “sustained interactions with industry or community professionals in real workplace settings...or simulated environments at an educational institution that foster in-depth, firsthand engagement with the tasks required in a given career field.” There are all kinds of models that fit this description.

Nevertheless, Assistant Secretary Stump is right that the new Perkins law is a great opportunity for states to invest in work-based learning programs. Here are a few ideas on how interested states could make it work.

Follow the lead of other states

There are plenty of states that have already invested considerable time, talent, and money into work-based learning programs. For instance, PrepareRI is an initiative of the Rhode Island state government that operates in partnership with businesses, schools, universities, and non-profits throughout the state. It is based on a strategic plan with eight priorities aimed at improving career readiness, and work-based learning is one of them. Specifically, PrepareRI calls for all high school students to have access to work-based learning at school by 2020. The state recognizes multiple varieties—including internships, service learning, and industry projects—and has published detailed guidance about each.

Another great example is Delaware, where the Delaware Pathways program provides high school and postsecondary students with work-based learning opportunities for in-demand careers. The program recently received a $3.25 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to, among other things, expand the Office of Work-Based Learning at Delaware Technical Community College.

Wisconsin is also doing good work. The Badger State has established a youth apprenticeship program as part of its statewide school-to-work initiative. It is designed specifically for high school students and integrates school-based and work-based learning within local programs in a variety of career fields.

Focus on partnerships and cross-sector collaboration

Perkins V allows states to use certain funds to establish statewide partnerships between middle and high schools, higher education institutions, employers, and other partners. In states like Rhode Island and Delaware, these partnerships already exist. But in places where they don’t, states should take advantage of the law’s flexibility and funding to establish them.

Take advantage of resources and tools

Whether states are looking to create new programs and frameworks or simply build on what already exists, there’s no need to start from scratch. Jobs for the Future, a national nonprofit that focuses on reforming both education and the workforce, has created a work-based learning framework and has published reports and a host of other resources through its Center for Apprenticeship and Work-Based Learning. New America recently examined the link between college and work-based learning and published eight recommendations for how to more effectively tie together apprenticeships and higher education. And this summer, the American Enterprise Institute released a report that examines how community colleges could play a more active role in growing apprenticeship opportunities.

In 2017, the National Center for Innovation in Career and Technical Education created a Work-Based Learning Tool Kit for state and local program administrators. It’s a treasure trove of data and information, including summaries of how work-based learning fits into federal legislation like Perkins, ESSA, and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act; recommendations for engaging employers, collecting data, and scaling programs; and links and resources from states that are leading the charge in work-based learning, such as North Carolina and Tennessee.

Incentivize businesses to participate

It’s a no-brainer that to make work-based learning viable, businesses will have to be involved. There are plenty of business that will jump at the chance to partner with schools and programs, but others may need additional enticement. That’s why states should consider creating a tax-credit program that would allow employers to reduce their state tax liabilities based on the number of students who complete work-based learning opportunities with their organization. By doing so, states could recruit new business and corporations to participate and help employers bear the costs of training and supervision, as well as wages in the case of apprenticeships.

***

Obviously, the information outlined here is not exhaustive. There are plenty of other resources out there and plenty of programs and partnerships that are already doing great work. But the most important thing to keep in mind is why work-based learning deserves to be a priority in every state: It provides students with meaningful opportunities to develop academic and career skills, it unites a broad range of partners—businesses, secondary and postsecondary education institutions, and community partners—in achieving a shared goal, and it has the potential to improve the state’s bottom line, as well as those of participants. Sounds like a win-win to me.