Texas is home to a fifth of the country’s English learners, as well as the state where the number of them has quintupled over the past decade. Recently, we published Charter Schools and English Learners in the Lone Star State, written by Deven Carlson with David Griffith. The study used nearly two decades of student-level data to examine how charter school enrollment is related to Texas English learners’ achievement, attainment, and earnings. You can read about all of the results here.

Jennifer Acevedo and Starlee Coleman are Data and Research Analyst and Chief Executive Officer at the Texas Public Charter Schools Association, respectively. The organization’s mission is to strengthen the policy and regulatory climate in Texas, such that every student has access to high-quality public school options. Given their key roles in the Texas charter landscape, we wanted their take on the report’s findings and how policies might be improved to support the education of English learners enrolled in charter schools. Here’s what they had to say on a quartet of questions.

1. What’s your overall reaction to the report? Was there anything that surprised you?

We are incredibly proud of, but not surprised by, the results of the report. These findings are consistent with data for the past several years showing that English learners in Texas public charter schools are outperforming on our state assessment and also on NAEP.

The finding that English learners from charter schools earn more money in the post-college years was especially exciting to see. There are quite a few charter schools in Texas that have created models focused on preparing students for both college and careers. For example, the School of Science and Technology offers pathways in engineering, biomedical sciences, and computer science that empower students to solve real-world challenges through engaging and hands-on learning projects. It is clear from test scores that English learners are being well-served by Texas charter schools during their K–12 years, but the findings regarding earnings shows that they are also receiving a strong foundation that leads them to lifelong success. This is the type of success we hope to see for all students.

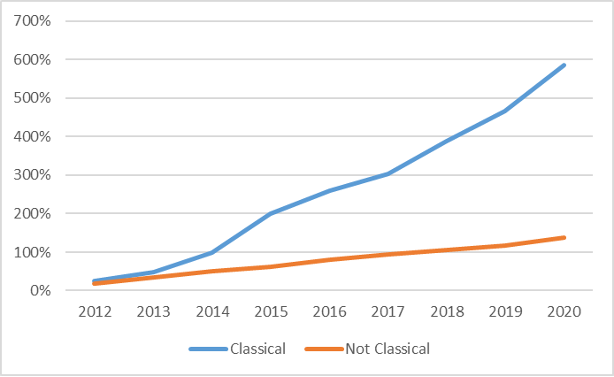

2. One question the report doesn’t answer is why English learners are increasingly overrepresented in Texas’s charter schools. What do you think might explain this trend?

We think this trend is potentially attributable to many factors, but let us highlight three.

First, many charter schools are founded with a specific mission to serve underserved communities, English learners included. When a school’s mission is to make students (and their families) with specific educational needs feel welcome and puts their needs front and center, it’s no surprise families are attracted to those school communities.

Second, success begets success. As Texas charter schools have proven their value in communities across the state, the waitlist for seats in high-performing campuses has grown (and now stands at approximately 66,000 students). Often, these families find out about a charter school by word of mouth.

Finally, in addition to serving more Hispanic students than traditional school districts (30 percent versus 21 percent), charter schools have more Hispanic teachers (37 percent versus 29 percent). And considerable research suggests that students of color who are assigned to teachers of the same race or ethnicity tend to have more positive experiences.

3. One point that came through very clearly in the interviews with practitioners was the almost universal demand for more bilingual educators, even in schools that don’t have an official bilingual program. The shortage of bilingual educators isn’t a new problem, of course, but is there anything to be done now, policy-wise, to address the problem? And if so, how can charter schools be part of that solution?

As always, there is no silver bullet. However, there are promising practices and policies that can make a difference.

One is to increase the number of pathways and training programs to become a certified bilingual educator. For example, quite a few charter schools in Texas have created “grow your own” teacher programs focused on identifying and developing prospective teachers to serve in hard-to-staff areas like bilingual education. Some of these programs provide high school students opportunities to explore the teaching profession, others provide support for paraprofessionals seeking certification, and still others are for teachers who want to pursue a graduate degree or a more specialized education certification. But regardless of their design, the goal is to capture and support talented educators who may not otherwise pursue the career.

Additionally, there is a longstanding disconnect between what it takes to complete a certain exam or certification requirement and what it takes to be a strong bilingual educator, especially in a dual-language teaching environment (where the teacher is typically speaking a lot of conversational Spanish). Most likely, the forms of assessment and certification can be modified to better capture the skills and knowledge needed to be a successful bilingual educator. (For example, instead of taking a standardized exam, teachers could present a sample lesson.) And charter schools can and should be advocates for this sort of flexibility.

4. Suppose you could make one policy change that you think would benefit English learners in Texas’s charter schools. What would it be?

While Texas is a leader when it comes to strong statewide policies for serving English learners in schools, there is always room to improve. One change that would be great to see is related to dual-language immersion programs. Though Texas recognizes the value of dual-language immersion programs for English learners and provides an additional bump in funding for schools operating those programs, that funding is dependent on teachers being fully certified as bilingual educators. As discussed before, there is a nationwide shortage of bilingual educators, and this is not a problem that will be quickly or easily solved. However, an uncertified teacher does not automatically mean that these are not high-quality dual-language programs achieving great outcomes for students, especially as seen from results of this study. Providing schools with the funding needed to continue to operate dual-language programs, regardless of teacher certification status, should be a priority. There was recent legislation aimed at addressing this, but time ran out before it could pass into law. We will continue to advocate on this issue in the future.

Jennifer Acevedo is the Data and Research Analyst at the Texas Public Charter Schools Association and a former bilingual educator in Texas charter schools.

Starlee Coleman is the CEO of the Texas Public Charter Schools Association and has twenty years of experience turning public policy ideas into laws.