Editor’s note: This is the first edition of “Advance,” a new newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute that will be written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on either the Fordham Institute website or the newsletter’s Substack.

The case for gifted education—or advanced education, honors education, or whatever one decides to call it—is simple. Every student deserves educational experiences that help them reach their full potential. Some children, due to high achievement, ability, or potential, require something more than can be provided in the average classroom geared toward the average student. Schools should therefore offer distinctive and high-quality advanced programs and services for those who would benefit from them. These students come from every racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic background, so for American education to fail in this regard is to fail some of the country’s most marginalized children.

Yet failure has tended to be the norm for decades, most notably for those very children. One-third of schools don’t devote any time or effort, during school, after school, or on the weekend, to their gifted students. Among those that do, “programs” may be nothing more than meager supplements that are unlikely to make much of a difference to achievement. In schools that manage to offer more robust programming, the staff often consists of teachers who have not been trained to educate these students. And regardless of whether schools avoid all the preceding pitfalls, virtually all under-identify and therefore under-serve low-income, Black, Hispanic, and Native American children.

But glimmers of hope are appearing on the gifted horizon. Through self-reflection, high-quality research, external pressure, and on-the-ground work, the field is improving. And that ongoing progress—tracking it, celebrating it, examining it, critiquing it when it runs afoul—is what this new newsletter is about.

Future issues, to be published every other week, will also be shaped by my experiences in the field. I’ve been writing about and researching gifted education for a decade, including a 2016 book coauthored with Chester Finn, a handful of reports for the Fordham Institute, and scores of editorials and policy articles in newspapers and education outlets. I’m also a consumer. As a child, I participated in a substantial—and, as I know now, very rare—full-time pullout program between fourth and eighth grade, wherein I was grouped with other advanced students for almost all instruction, complete with different teachers, specialized curricula, and faster and deeper instruction. This program was especially formative for me, in many good and a few bad ways, and it prompted my lasting interest in this realm of K–12 education.

All this experience solidified in me two simple truths about gifted education: It is a clear and substantial good, and it can be much better than it is in most places and has been for decades. Two recent developments have given me hope that many others are coming to believe this, too. They suggest that high-quality advanced programs will persist in America and, just as importantly, that they will serve more of the children who would benefit from them—and deserve to benefit from them—especially kids from underserved backgrounds. The first development happened in San Francisco last month. The second took place over Zoom last week.

During the pandemic, San Francisco’s school board voted to suspend merit-based admissions at Lowell High School, the area’s most prestigious institution, and install a lottery-based system that was open to all students. Many residents, especially Asian-American voters, were incensed by the decision. And earlier this year, driven in no small part by the Lowell reform, the city overwhelmingly voted to recall three school board members, with more than 70 percent supporting each member’s ouster.

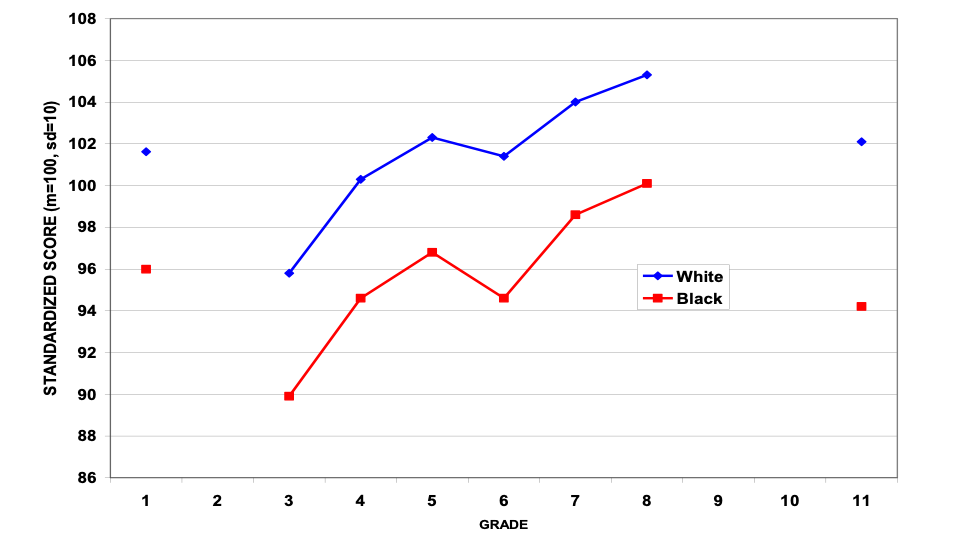

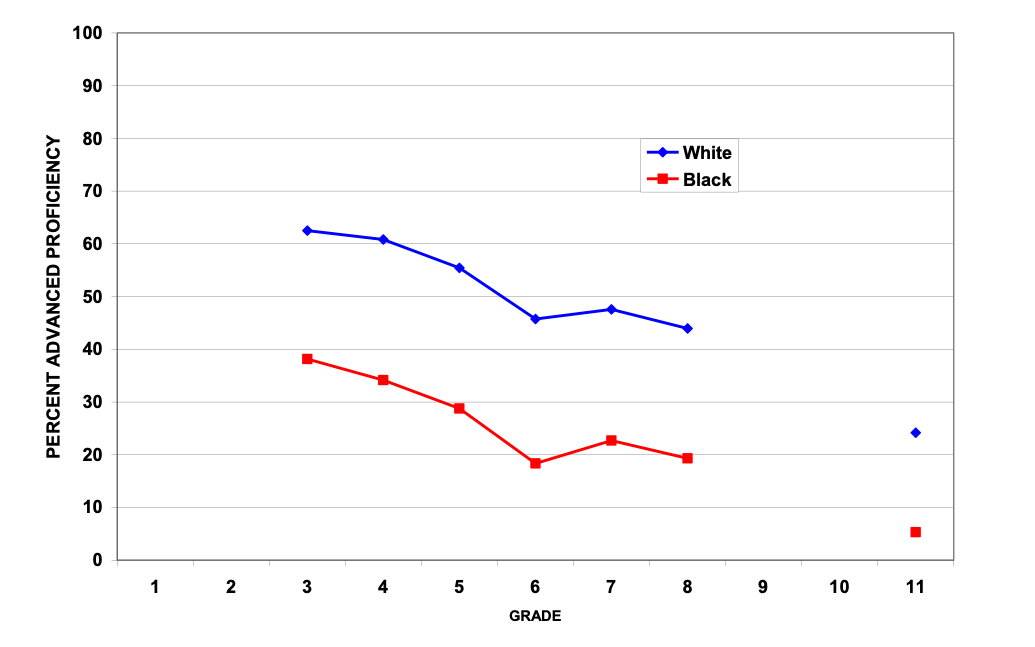

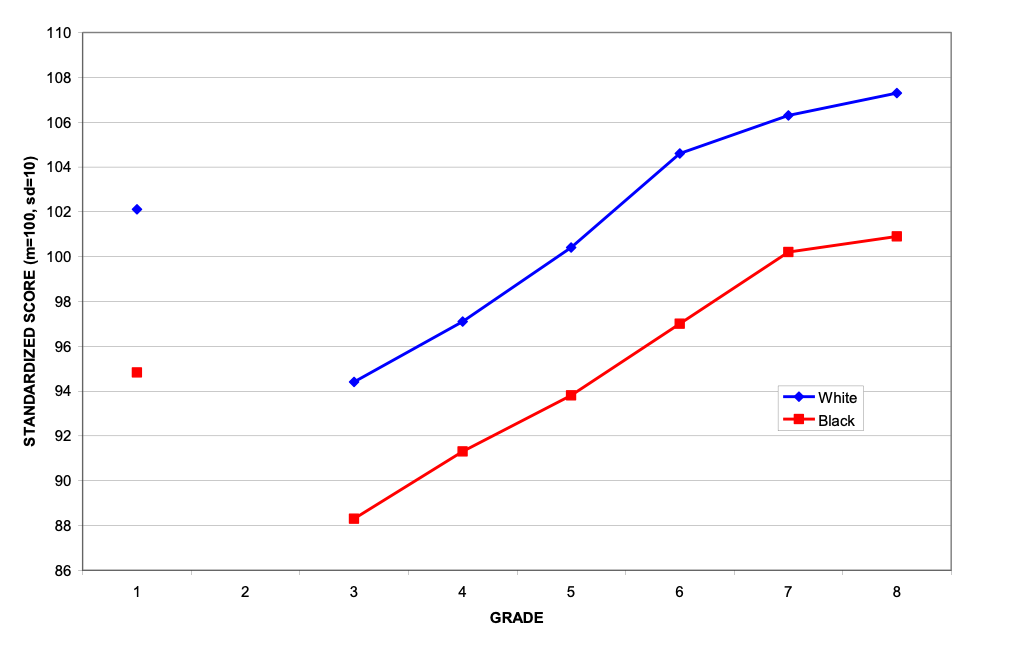

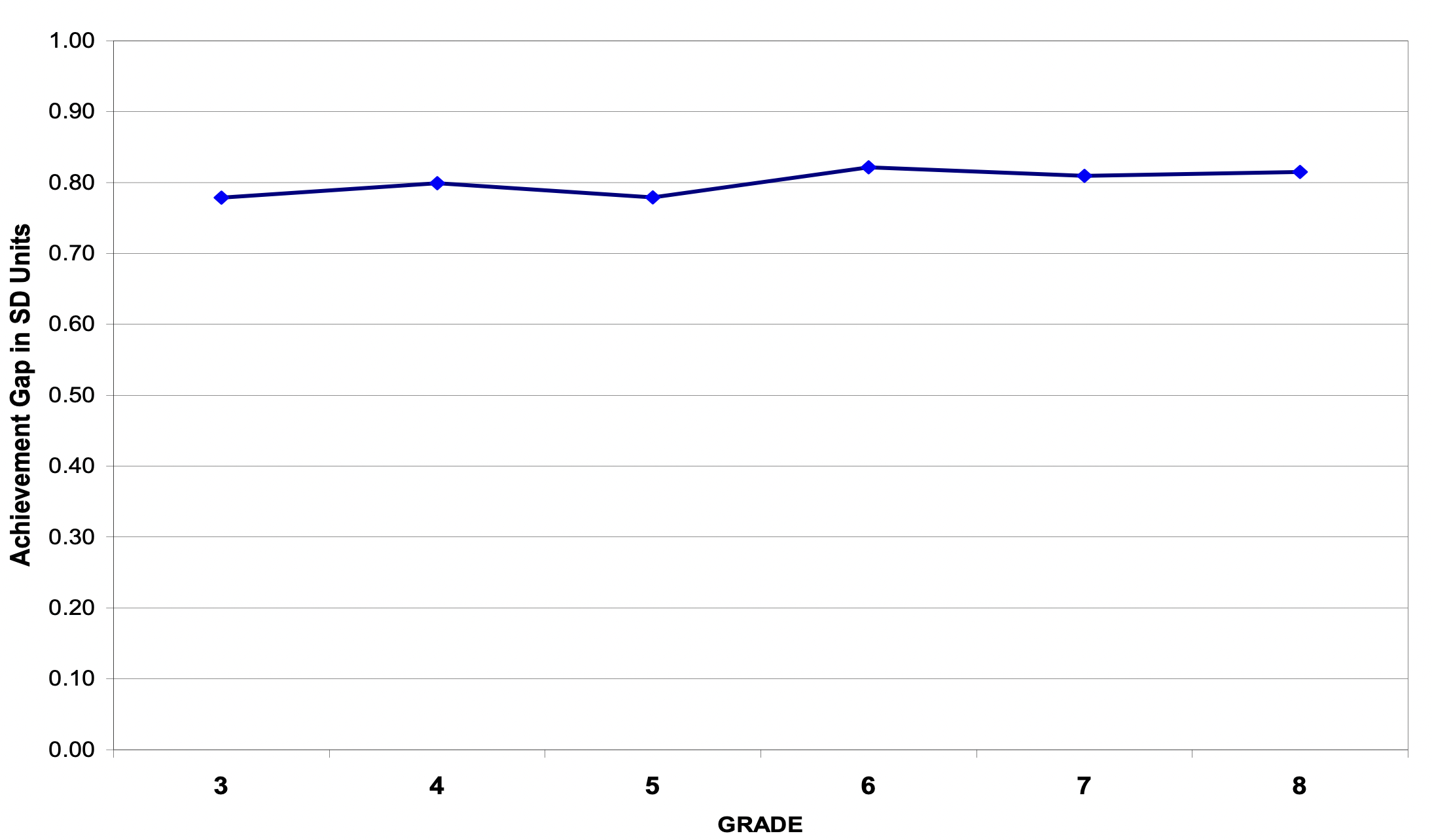

Last month, those efforts bore fruit when the board voted 4-3 to reinstate the school’s merit-based system, meaning entry will again be determined by applicants’ grades and test scores. Important, too, was the board majority’s commitment to, as the San Francisco Chronicle reported, “confront the real equity problems in the district while also supporting academic excellence.” Hispanic and Black students make up 12 percent and 2 percent of Lowell students, respectively, despite those figures being 28 percent and 6 percent citywide. So leaders have significant work to do in identifying many more of the marginalized students who would benefit from what Lowell has to offer—even if a majority of its present pupils are Asian-Americans, a marginalized population in its own right. For this to succeed, they should start well before it’s time to apply to Lowell. As my colleague Mike Petrilli has shown, the achievement and instructional gaps that lead to discrepancies in these programs open as early as kindergarten, and the more they widen the harder they are to overcome.

The second development, which occurred over Zoom, was the second meeting of the National Working Group on Advanced Education. There’s twenty of us, including academics, practitioners, and advocates, and we’re truly diverse in terms of ideology, race, gender, and geography. In this second of four gatherings, we covered four topics: supports for advanced students who are Black, Hispanic, and/or low-income; support for educators of advanced students; high-quality instructional materials; and how best to use ability or achievement grouping. (A full summary will soon be published on Fordham’s website.)

For a very long time, gifted education has been both excessively standardized and exclusive. It has generally erred in considering “giftedness” to be an inherent trait that a student either has or doesn’t, and it has treated it as applying to virtually all academic subjects, regardless of each child’s unique strengths and weaknesses. This has caused at least two significant problems. One is that students who are advanced in a given subject but aren’t, according to the school, “gifted” have been excluded from whatever passes for gifted programming in that subject. The second is that schools and their identification procedures for these offerings have been, almost everywhere, plagued by bias against students who are Black, Hispanic, low-income, and come from other underserved backgrounds. Many children from these populations who could and should enjoy the benefits of these programs have therefore been excluded—or at least never been sought out and included.

Everyone in our group agreed that these are problems that need to be solved. But members also offered ample evidence that efforts are already underway to chip away at them. They talked, for example, of a push toward a personalized “continuum of services” that replaces binary “gifted or not” thinking. This attempts to give individual students what they need in each academic subject. As the National Association for Gifted Children explains, these services range from students receiving services in regular classrooms, to learning in a mix of regular classes and some advanced ones, to being grouped most of the time with other advanced students, to skipping grades entirely.

Other members also summarized fantastic work in transforming gifted education so it better supports, identifies, and retains students from underserved backgrounds. For example, one member explained how he and colleagues had taken an off-the-shelf program for advanced students and made it culturally relevant. In a low-performing school that predominately served Black students from a low-income community, they took an afterschool math program and paired it with basketball, which they designed specifically for Black males. Combining the activities in this manner helped the school increase the number of Black students identified as gifted from four to thirty-five in just four years.

The working group member said this worked, in part, because early success helped alleviate teachers’ “gifted referral fatigue.” This is a term coined by Dr. Tarek Grantham, a professor at the University of Georgia and a member of that working group, that represents his observations of teacher referral patterns. For years, educators had seen potential in many of their Black male students and referred them to gifted programming, but they kept being rejected, so the referrals ceased. It also helped students who started the program stick with it because it offset the effects of “stereotype threat.” This is where a person’s performance in a given situation is hindered by negative stereotypes about the abilities of that person’s groups. Black males, the member said, were worried about how they’d perform or what their peers would think of them. The work done by the program leaders to ease these concerns helped them retain more students and ensure that they kept receiving its benefits.

It's wonderful and striking that, in America as we pass Independence Day 2022, such a diverse group can agree on a unified way to accomplish so many things: getting more schools to adopt more gifted education services, especially those that educate marginalized populations; ensuring that such services are high quality and flexible and meet individual student needs; making those services more inclusive by offering them to every child who may realistically benefit; communicating all of this in a manner that emphasizes the benefits for those from underserved backgrounds; and implementing culturally responsive adaptations so as to much better prepare, identify, retain, and support marginalized students in advanced programs.

Gifted education is a fine thing when done well. For far too long, it hasn’t been. But with support for maintaining it in places as progressive as San Francisco, as well as a bipartisan vision for doing it better everywhere and for students of all backgrounds, there is hope that the progress already underway will continue.

Future editions of the newsletter will give updates on how that progress is going, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. If you have any ideas, leads, questions, or concerns, please email me at [email protected]. My hope is that we can help advance this field together.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“‘[Success] doesn’t make us unhappy,’ Dr. Lubinski said. ‘People who choose to be highly successful in their careers shouldn’t worry that they’re putting themselves at risk for medical or psychological harm.’ This might sound intuitive to anyone other than Freud. Of course success doesn’t make us unhappy! But what’s remarkable is how counterintuitive it happens to be.”

—“The happiness data that wrecks a Freudian theory.” The Wall Street Journal, Ben Cohen, June 30, 2022.

—

THREE RECENT STUDIES TO STUDY

- “The Challenges of Achieving Equity Within Public School Gifted and Talented Programs,” by Scott J. Peters. Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 66, Issue 2, 2022.

“K–12 gifted and talented programs have struggled with racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, native language, and disability inequity since their inception... The purpose of this article is to outline why such inequity exists and why common efforts to combat it have been unsuccessful. In the end, poorly designed identification systems combined with larger issues of societal inequality and systemic, institutionalized racism are the most likely culprits.”

- “Reflections on Experiences at a Residential Science and Math High School: An Alumni Survey,” by Hope E. Wilson. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, Volume 44, Issue 4, 2021.

“This study examines the results of a retrospective survey from one [residential science high school that focuses on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics], including alumni for more than 20 years after graduation. The results indicate that the alumni have high levels of educational attainment and careers in STEM fields. In addition, the alumni perceive their experiences at the RSHS to have been positive, and that the RSHS prepared them for their educational pursuits, careers, social experiences, and future leadership positions.”

- “Psychological Well-Being of Intellectually and Academically Gifted Students in Self-Contained and Pull-Out Gifted Programs,” by Trent N. Cash and Tzu-Jung Lin. Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 66, Issue 3, 2022.

“This study examined the psychological well-being of students enrolled in two gifted programs with different service delivery models. Students...reported different patterns of psychological well-being when compared with students in the no gifted services control group.”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

- “Johns Hopkins summer programs canceled as some students are en route.” The Washington Post, Donna St. George, June 27, 2022.

- “Helping gifted students get through summer.” The Washington Post, Letters to the Editor in response to news of cancelled Johns Hopkins summer programs, July 1, 2022.

- “The happiness data that wrecks a freudian theory.” The Wall Street Journal, Ben Cohen, June 30, 2022.

- “NYC’s specialized high schools continue to admit few Black, Latino students, 2022 data shows.” Chalkbeat, Christina Veiga, June 15, 2022.

- “3 Out of 4 Gifted Black Students Never Get Identified. Here’s How to Find Them.” Education Week, Sarah D. Sparks, June 03, 2022.

- “How to narrow the excellence gap in early elementary school.” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Michael J. Petrilli, June 2, 2022.

—

FYI

NAGC22 registration is now open

Happening in Indianapolis from November 17–20, this will be the National Association of Gifted Children’s 69th Annual Convention. Each year, it’s the largest gathering devoted to gifted and talented education. As its prospectus notes, the “convention will bring 2,000+ attendees in person from around the world who are dedicated to supporting the needs of high-ability children.” Learn more.