It pays to increase your word power

Education for upward mobility starts with building low-income students’ vocabulary. Robert Pondiscio

Education for upward mobility starts with building low-income students’ vocabulary. Robert Pondiscio

To grow up as the child of well-educated parents in an affluent American home is to hit the verbal lottery. From their earliest days, these children reap the benefits of parents who speak in complete sentences, engage them in rich dinner table conversation, and read them to sleep at bedtime. Verbal parents chatter incessantly, offering a running commentary on vegetable options in the produce aisle, pointing out letters and words in storefronts and street signs. Parents proceed, as Ginia Bellafante of the New York Times once put it, “in a near constant mode of annotation.”

In sharp contrast, early disadvantages in language among low-income children—both the low volume of words they hear and the way in which they are employed—establish a verbal inertia that is immensely difficult to address or reverse. Schools will spend every moment trying to make up for the verbal gaps kids come to school with on Day One, which usually grow wider year after year.

When it comes to vocabulary, size matters. E.D. Hirsch, Jr. observed that vocabulary “is a convenient proxy for a whole range of educational attainments and abilities.” It signals competence in reading and writing and correlates with SAT success—which, in turn, predicts the likelihood of college attendance, graduation, and the associated wage premium that has been fetishized by education reformers and driven their agenda for decades.

But vocabulary is important even for kids whose pathway to the middle class does not include college. Studies of the Armed Forces Qualification Test show that the test predicts job-performance and income gains most accurately when you double the verbal score and add it to the math score. In short, those old Reader’s Digest vocabulary quizzes had it exactly right. It really does pay to increase your word power.

What’s the best way to build vocabulary? If you went to college, there was probably a point during your junior or senior year of high school when you devoted many tedious hours to rote memorization of “SAT words.” Perhaps some of them found their way into your repertoire—assiduous, enervating, perfidious—and you use them to this day. However, the overwhelming majority of words you know and use were not learned through memorization, but by repeated exposure to unfamiliar words in context until they became part of your working vocabulary

Among educators, vocabulary is often described as “tiered.” Tier-one words include basic words that most native speakers come to school with regardless of upbringing: baby, dog, run, chair, happy. Tier three represents specialized vocabulary associated with specialized domains of knowledge and rarely heard elsewhere, such as isotope or exposition. The sweet spot for vocabulary growth and language proficiency are tier-two words, which occur in a variety of domains. Words like verify, superior, and negligent are common to sophisticated adult speech and reading; we perceive them as ordinary, not specialized language. Tier-two words are essential to reading comprehension and undergird more subtle and precise use of language, both receptive (reading, hearing) and expressive (writing, speaking).

Consider how a child might come to encounter the tier-two word “durable.” She would need multiple exposures to the word—not memorization. Here are some potential uses of the word “durable” she might encounter culled from children’s books, websites, and advertisements:

“The Egyptians learned how to make durable sheets of parchment from the papyrus plant.”

“With this lightweight and durable telescope, young scientists can explore the natural wonders of the earth or the craters of the moon and beyond.”

“Many durable ancient Roman concrete buildings are still in use after more than 2,000 years.”

“Instead of having to find caves or create makeshift shelters for protection from the weather, man started to look for more durable materials with which to build long-lasting dwellings”

In order for the vocabulary-building process to work, she must understand the gist of what she hears or reads and be able to contextualize the unfamiliar new word in each exposure. In the examples above, terms like “Egyptians,” “parchment,” “papyrus,” “makeshift shelters,” and “concrete” lend sense and meaning to the word “durable.” Without the enabling context, the word “durable” is one among many in the sentence or utterance she is unfamiliar with, and language growth stalls. This is the Matthew Effect in action: Those who have the broadest general knowledge, whether acquired at home, school, or elsewhere in their lives, are most likely to possess the “schema” necessary to intuit the meaning of the word in context and ultimately incorporate the new word into their vocabulary; those who do not fall further behind. The language-rich grow richer; the poor get poorer.

Seen through this lens, it is immediately and abundantly clear that the key to language growth is the broadest possible knowledge base—the context-creating engine of language growth. And it proceeds from this that the best way to ensure language growth is a primary education that is as rich and varied as possible. In short, schools that hope to educate for upward mobility should be doing all they can to make children as rich as possible in knowledge and language—so that they can grow richer still. To be avoided at all costs is any impulse to narrow curriculum to an ill-conceived regimen of reading skills and strategies at the expense of a well-defined curriculum constructed around coherent, sequential, and rich domain-based content. Low-income children most specifically need more, science, social studies, art, and music to build the necessary “schema” that drive comprehension and language growth.

It goes firmly against the grain of current pedagogical fashion and political tradition, but regardless of where one attends school—for reasons of language development, skills development, and civic engagement—there should be far more similarities than differences in the content of K–8 education in America. The promise of preparing children for academic achievement and upward mobility depends upon a base level of language proficiency. Elementary and middle school education should set the stage for independent exploration. It should not be independent exploration. Insisting on hyper-local choice and encouraging wild variation in content within and across schools, districts, and states makes no more sense than insisting on a local alphabet.

To put the matter bluntly, language cares little about education homilies about child-centered schools and culturally relevant pedagogy. Language cares even less about local control of curriculum. There is a language of upward mobility in America. It has an expansive and nuanced vocabulary that it employs to nimbly navigate the world of organizations, institutions, and opportunities.

Without a common body of knowledge and its associated gains in vocabulary and language proficiency as a first purpose of American education, the achievement gap will remain a permanent fixture of American society, and the odds of upward mobility—already depressingly long—will become nearly insurmountable.

This essay was adapted from a longer paper released at the "Education for Upward Mobility" conference on December 2 and will be featured in a book to be released in 2015.

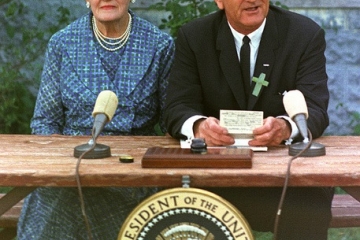

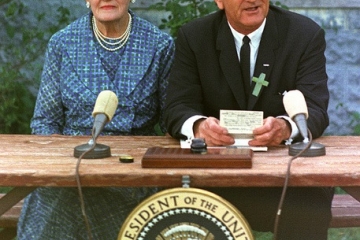

If you stop and listen, you can hear it: The country yearning, praying, hoping for some sign that our political leaders can get their acts together and get something done, something constructive that will solve real problems and move the country forward again. In 2001, in the wake of 9/11, that something was the No Child Left Behind Act, which was the umpteenth renewal of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). A reauthorization of the ESEA (on its fiftieth anniversary no less) could play the same role again: showing America that bipartisan governance is possible, even in Washington.

Thankfully, both incoming chairmen of the relevant Senate and House committees—Lamar Alexander and John Kline—have indicated that passing an ESEA reauthorization is job number one. And friends in the Obama administration tell me that Secretary Duncan is ready to roll up his sleeves and get to work on something the president could sign. So far, so good.

So what should a new ESEA entail? And could it both pass Congress and be signed by President Obama? Let me take a crack at something that could.

First, let’s set the context. For at least six years, we at the Fordham Institute have talked about “reform realism” in the context of federal education policy—recommending that Washington’s posture should be reform-minded, but also realistic about what can be accomplished from the shores of the Potomac (and cognizant of how easy it is for good intentions to go awry). While Secretary Duncan gave early, encouraging indications that he supported such an approach, in recent years, regrettably, his department has moved ahead with an aggressive, constitutionally questionable policy of conditional waivers, leading to a fierce backlash against federal overreach. (Of course, his actions and statements on Common Core haven’t helped, either.)

So it’s even more important than it was six years ago, both politically and substantively, that a reauthorized ESEA pay heed to the “realism” part of reform realism. Put another way, no ESEA will be supported by the next Congress—at least by its Republican majority—unless it shortens Uncle Sam’s leash. If you don’t believe that the federal role should be smaller than it is today, then you can’t claim to be serious about wanting ESEA to be reauthorized. Not in the 114th Congress.

That doesn’t mean that Washington must foreswear reform. To devolve everything to the states would be much like saying, “Here’s fifteen billion dollars in Title I money a year—do whatever you want with it.” The federal government may be a minority investor, but it still has a duty to demand something constructive in return. (Call it accountability for the taxpayer’s dollar.)

The challenge, then, is to find the right spot on the continuum between today’s coercive, micromanaging federal role and “leaving the money on the stump”—a spot that is realistic about Washington’s proper role (and capacity) in the education cosmos, but that still nudges the system in a reform direction.

The elements of a new ESEA

In my view, that means a big focus on transparency, both around student achievement (disaggregated every which way) and around spending (at the school level). And that’s it.

In particular, it would mean:

Everything else will be left on the cutting room floor—specific requirements about interventions in failing schools; mandates around teacher evaluations or “highly qualified teachers”; competitive grant programs a la Race to the Top. This new ESEA will be lean and clean.

I could picture such a bill passing both chambers of Congress, probably with a fair number of Democrats voting aye. And if the president wants to disentangle the education reform movement from today’s vitriolic debates over the federal role, he would be smart to sign it.

Will that actually happen? Who knows? But it sure would be a great way to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of the ESEA.

The importance of vocabulary, ESEA reauthorization efforts, school discipline, and how school environment affects teacher effectiveness.

Amber's Research Minute

Matthew A. Kraft and John P. Papay, “Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 36, No. 4 (December 2014).

A core assumption of the education-reform movement is that excellent schools can be engines of upward mobility. But what kind of schools? And to what end?

In tandem with the release of several papers, this path-breaking conference will consider thorny questions, including: Is “college for all” the right goal? (And what do we mean by “college”?) Do young people mostly need a strong foundation in academics? What can schools do to develop so-called “non-cognitive” skills? Should technical education be a central part of the reform agenda? How about apprenticeships? What can we learn from the military’s success in working with disadvantaged youth?

Keynote Address: Hugh Price, Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution “What the Military Can Teach Us About How Young People Learn and Grow”

It’s been nearly fifty years since the publication of “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” remembered by history simply as “the Moynihan Report” after its author, future United States Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who in 1965 was an assistant labor secretary. The report detailed the decay of the black two-parent family and the concomitant social and economic problems. In this article in Education Next, the first in an entire issue dedicated to the Moynihan Report, Princeton professor Sara McLanahan and Christopher Jencks of Harvard’s Kennedy School ask, “Was Moynihan right? What happens to the children of unmarried mothers?” Note the race-neutral formulation. The authors aren’t attempting to avoid an inflammatory question. Rather, they’re addressing a problem now far more widespread than it was when Moynihan wrote. The rate of unmarried births among whites today is considerably higher than the 1965 rate among blacks, which troubled Moynihan enough to issue his bombshell report. Indeed, an estimated half of all children in the United States live with a single mother at some point before they turn eighteen. This portends many different outcomes, none of them good. The authors cite a recent review of forty-five studies using quasi-experimental methods, which find that growing up apart from one’s father reduces a child’s chances of graduating from high school by about 40 percent. Interestingly, the absence of a biological father has not been shown to affect verbal and math test scores. The disconnect seems to be attributable to another ill effect of a fatherless childhood: an increase in antisocial behavior such as aggression, rule breaking, delinquency, and illegal drug use. “Thus it appear that a father’s absence lowers children’s educational attainment not by altering their scores on cognitive tests but by disrupting their social and emotional adjustment and reducing their ability or willingness to exercise self-control,” McLanahan and Jencks note. These effects are larger for boys, which means the increase in single-parent families may also be contributing to widening gender gaps in college attendance and completion. Would these kids be better off if their biological parents were married? Not necessarily. Children with unmarried mothers are more likely to have a biological father who is in prison, beats his partner, or cannot find or hold a job. So what can be done? There’s no really satisfactory answer, though the authors assert that a good starting point is to give girls and women a good reason to postpone motherhood. “But, we also need to improve the economic prospects of their prospective husbands,” they add, “especially those with no more than a high school diploma.” Pretty much what Moynihan said fifty years ago.

SOURCE: Sara McLanahan and Christopher Jencks, “Was Moynihan Right?,” Education Next, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Spring 2015).

This study examines the impact of peer pressure on academic decisions. Analysts Leonardo Bursztyn and Robert Jensen conducted an experiment in four large, low-performing, low-income Los Angeles high schools whereby eleventh-grade students were offered complimentary access to a popular online SAT prep course. Over 800 students participated. Analysts used two sign-up sheets, which they randomly varied. One told students that their decision to enroll would be public, meaning their classmates would know they signed up; the other told them it would be kept private. The key finding is that, in non-honors courses, sign-up was 11 percentage points lower when students believed others in the class would know whether they agreed to participate, compared to those who were told it would be kept private—suggesting that these adolescents believe there is a social cost to looking smart. In honors classes, there was no difference in sign-up rates under the two conditions. Because students in honors and non-honors classes obviously differ, to help mitigate selection bias, Bursztyn and Jansen then examined results only from students who took two honors classes—some of whom would be sitting in honors classes when they were offered the decision to participate and some of whom would be sitting in non-honors courses. They found that making the decision to enroll "public" rather than private decreases sign up rates by 25 percentage points when the “two-honors-class” students are in one of their non-honors classes. Yet when students are in one of their honors courses, making the decision public increases sign up rates by 25 percentage points. Moreover, based on student surveys, students in non-honors classes who say it is important to be popular are less likely to sign up when the decision is public rather than private, whereas students who say it is not important are not affected at all. Changing cultural norms is obviously a difficult thing to do, but we need to recognize that, when actions are observable, some kids may act counter to their best interests.

SOURCE: Leonardo Bursztyn and Robert Jensen, "How Does Peer Pressure Affect Educational Investments?," National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 20714 (November 2014).

Most of us have known students who struggle with non-cognitive skills. Teachers have labored heroically to keep a reserved pupil engaged in group projects; parents have cajoled a discouraged child to keep working through a multi-step equation; even a few education writers, in our misguided youths, put off a term paper or two until the night before the end of the semester (I’m sure it got lost in your inbox, Professor Kaiser). Melissa Tooley and Laura Bornfreund’s new study for the New America Foundation looks at how high-quality early-education programs impart critical, non-content-oriented traits like work ethic, curiosity, teamwork, and empathy—abilities they label “skills for success” and thereafter, somewhat gratingly, refer to as “SFS”—and how those approaches can be replicated and expanded at the K–12 level. Their findings represent a worthwhile and informative new entry into a debate that’s suddenly grown hot. For their part, the authors are quickly forced to address one obvious pitfall: the difficulty of quantitatively determining a student’s progress in attaining better emotional and behavioral habits, other than perhaps locking a four-year-old in a room with a marshmallow and telling him to exercise grit. “It may not currently be possible to assess certain skills well at all,” they concede. What can be assessed, however, are classroom and school environments, which research suggests have an outsized effect on students’ development of skills for success. Using surveys like the Comprehensive School Climate Inventory (CSCI) and Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), it is possible to measure and compare schools’ safety profiles, interpersonal relationships, and institutional supports for students and staff—all of which can impact how effectively students learn (and teachers teach) lessons on multiplication tables and geography. Among the usual calls for more research and better communication from state and local authorities, Tooley and Bornfreund’s most compelling recommendation is that these assessment results be made transparent and widely available, just like standardized test scores and spending data. It’s a smart take on a complex topic—just like my junior year paper on Thomas Mann would have been, if I’d had a little more grit.

SOURCE: Melissa Tooley and Laura Bornfreund, “Skills for Success: Supporting and Assessing Key Habits, Mindsets, and Skills in PreK–12,” New America (November 2014).