Trust, but verify

The era of judging New York City Schools on academics is over. Robert Pondiscio

The era of judging New York City Schools on academics is over. Robert Pondiscio

With little fanfare, the New York City Department of Education (DOE) last month released a draft of its new “School Quality Snapshot”—Chancellor Carmen Fariña’s bid to evaluate each of Gotham’s more than 1,800 schools based on “multiple measures.” The DOE’s website invites public comment on the new reports until May 8. Here’s mine:

I confess I wasn’t the biggest fan of the single-letter-grade school report cards of the Bloomberg-Klein era. But as a signaling device to schools and teachers about what mattered to the higher-ups at the DOE’s Tweed Courthouse headquarters, they were clear and unambiguous: Raise test scores, but most importantly raise everyone’s test scores. With 85 percent of a school’s grade based on test scores—and 60 percent of the total based on test score growth—the report cards, for good or for ill, left little room for doubt that testing was king. Valorizing growth was an earnest attempt to measure schools’ contributions to student learning, not merely demographics or zip code.

Fariña, whose contempt for data I’ve remarked upon previously, values “trust.” You may worry if your child can’t read or do math. So does Chancellor Fariña, sort of. But she deeply cares if “teachers trust the principal at his or her word,” whether “teachers trust each other,” if students say teachers treat them with respect, and if parents say that a school’s staff “works hard to build a trusting relationship with parents.” The signal feature of the new report cards is the warm, enveloping embrace of the circle of trust.

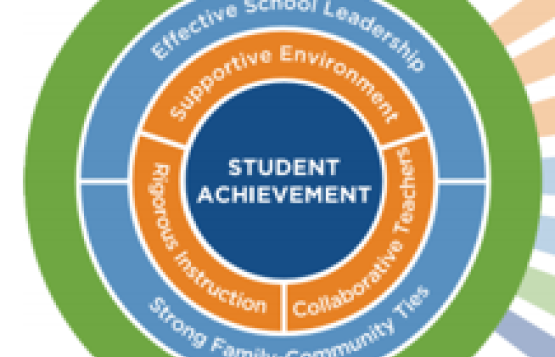

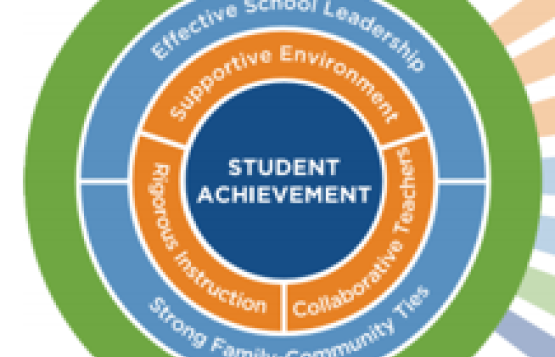

Other elements of the draft Snapshot are equally warm and fuzzy. Sure, “rigorous instruction” is on top, but “student achievement,” like the proverbial pony, is buried beneath a pile of collaborative teachers, supportive environments, and strong family-community ties. In short, this document feels driven more by philosophy than data, relying on qualitative measures of uncertain value while strongly de-emphasizing student achievement in general and student growth specifically.

When she announced her intention to overhaul the school report cards last year, Fariña promised “the first balanced picture of a school’s quality,” one that “reflects our promise to stop judging students and schools based on a single, summative grade.” To be fair, it was widely acknowledged even in the pre-Fariña DOE that the reductive nature of the school report cards was having unintended ill effects. A 2013 white paper noted that the existing progress reports’ overreliance on state tests meant that “some educators have felt pressure to engage in test prep, narrowing the curriculum,” and that “finding the right balance of multiple measures is critical.” Even top-performing schools were anxious about their letter grades.

However, there are a couple of serious problems with this offering. Like a driver overcorrecting and losing control, the new reports go from focusing almost exclusively on student achievement to making it one of seven areas of reporting. And where 85 percent of a school’s value was based on test scores in the past, no weighting is given to any area of evaluation in the new reports. The biggest and potentially most troubling change is the removal of a coherent growth methodology by which schools are measured. The risk in de-emphasizing growth is that it might push schools and teachers back to focusing on how many kids pass the tests, which incentivizes focusing on “bubble kids” at or near the passing line. If a school’s going to be successful, everyone needs to improve.

If test data isn’t driving the new Snapshot, what is? Most of the information comes from the NYC School Survey administered annually to parents, teachers, and students, or else from a school’s “quality review”—ostensibly an extensive school visit in which an experienced educator observes classrooms, interviews school leaders, and evaluates how well the enterprise supports student achievement. Curriculum, teaching, assessments, school culture, and teacher collaboration are among the areas scrutinized during each school’s review.

In theory, it’s a robust and useful lens through which to view a school. At present, though, not every New York City school is reviewed every year (it’s been three years since some schools have been reviewed). Worse, there are reports that what used to be a rigorous three-day inspection is now being performed in as little as half a day—little more than a drive-by. (A DOE spokesperson has not responded to a request for comment on the number or duration of reviews performed or scheduled this year). Meanwhile, charter schools are not subject to quality review at all, which will render the Snapshots virtually meaningless (many growth-focused charters, it should be noted, benefitted mightily from the single-letter-grade report cards).

A former DOE official lamented to me privately that nearly everyone with data expertise was driven out of Tweed when Fariña took over. Thus, perhaps the greatest concern is not even the new Snapshots’ favoring qualitative measures over student achievement, but Tweed’s capacity to gather meaningful, high-quality data even on the things it prizes.

In sum, balancing achievement data with a quality review makes good sense; it was the direction in which the DOE was headed even before Fariña . But devaluing test data—combined with infrequent or cursory reviews—risks making what should be a dynamic and useful report to parents and teachers either static or a mere exercise in confirmation bias. At heart, New York City’s School Quality Snapshot feels like a political text. It is not hard to foresee it casting a warm glow on the kinds of schools Fariña likes, whether or not student achievement is robust.

Having worked in a DOE school for several years, I can attest that schools focus on gestures from Tweed as if they were smoke signals from the Sistine Chapel when a new pope is chosen. Thus, the most important function these reports serve is to indicate what matters to schools and teachers. The draft School Quality Snapshot says clearly and unambiguously that the days of measuring a school by academic performance in New York City are over.

In early April, I wrote that school choice is the highest form of fairness because it rewards positive behavior and aligns the interests of parents, children, and schools. Some disagree, arguing that school choice disadvantages the non-choosers. It is admirable to want to protect the most vulnerable students—the children of parents who do not or cannot engage effectively. But we must not do this at the expense of families who are engaged and do make good decisions for their kids.

As we parents often remind our children, two wrongs don’t make a right.

By encouraging parents to make choices, we also send an important message to students about our values. For the kindergartners at my school, a choice might be as simple as how to share the wooden blocks with a new friend. This simple and safe experience helps them practice the larger and more consequential decisions they will face.

Across the income spectrum, the parents I’ve met are concerned with our failure in both schools and civil society to inculcate critical values in our children. Research affirms the importance of persistence, delaying gratification, and other “gritty” non-academic values. If we ignore parent behaviors in the name of fairness, how can we expect children to appreciate those values?

A recent episode of This American Life underscored this dilemma. The reporter followed students from University Heights High School in the Bronx, a school whose poverty is inversely proportional to its proximity to Fieldston, one of New York’s famously wealthy private schools. The two schools operated an exchange program that allowed the largely underprivileged students from University Heights to glimpse the incredible opportunities available to those at Fieldston.

Speaking of her freshman year, a University Heights student named Melanie recalled the first few days. “This has got to be a joke…They don’t offer any AP classes….We didn't have a library, and I love books….We’re really in a poor part of the Bronx where we’re not being considered.”

Despite starting at a deep disadvantage, Melanie quickly emerged as one of the kids who would make it to college. Nominated for a prestigious (and highly competitive) Posse scholarship, her teachers and peers could all see her at Middlebury. But when she was dropped in the final round, Melanie lost her way completely.

Tracked down a decade later at the grocery store where she is now employed, Melanie acknowledged that she does the work she’d always hoped to escape: “wearing the uniform, servicing these people.” She meant the ones who'd gone to Fieldston.

But she knew that she was the one to blame: “I just grew angry at myself for making that choice of saying, ‘Well, I’m going to accept this,’ instead of fighting against it.” Melanie saw that losing out on the scholarship didn’t have to be the end of her dream. By failing to respond to the many teachers, both at University Heights and Fieldson, who reached out to her and wanted to support her, she let that happen.

The same reporter spent time with Jonathan Gonzalez and Raquel Hardy, classmates of Melanie’s who’d won scholarships to two esteemed colleges. Their paths were not much easier. Hardy told the reporter, “In the beginning, I struggled too. My first year, I got C-pluses and B-minuses. It was devastating to me because I was an A-plus student in high school, and we both were like, ‘This is a lot. This is crazy. I wasn't expecting this.’”

Her boyfriend Jonathan could not afford to buy textbooks and, embarrassed by his poverty, started skipping classes and hiding in his dorm room. Raquel, who faced the same struggle at her own school but knew to ask for help, told Jonathan to go to the university library.

I run a Brooklyn charter school, and I discussed this story with our Director of Operations, Ferrugia Sonthonax. “Oh,” Ferrugia told me, “I applied for a Posse too.“ Like Melanie, she did not win. But like Raquel and Jonathan, she knew to keep trying.

For Ferrugia, college was only a question of where, not if. Like generations of immigrant children before her, she attended the City University of New York and continued down the path her Haitian-born parents had always expected for her.

Critics of choice point to the Melanies and ask, “What if someone had tried harder to help her?” Speaking for myself, I wonder, “What if we helped to foster more Raquels, Jonathans, and Ferrugias?

The trolley problem is a thought experiment that asks if it is acceptable to harm one person to save five from a runaway train. Throw the switch and one person will be crushed; don’t, and five others will. The ways we respond to this ethical dilemma underscore our humanity.

Life is all about choices. Before critics denounce parents who look for alternatives to schools that routinely fail to prepare their students for meaningful participation in civil society, let’s hope they acknowledge the moral choice we are making for them.

Matthew Levey is the executive director of the International Charter School, a Brooklyn elementary school opening this fall. His three children attend New York City public schools.

Standardized tests, rural education reforms, social mobility, and teacher turnover.

Amber's Research Minute

Alyssa: Thank you. Thank you. That's quite the aspirational title, Michelle. Please do not ask me to sing for your own sake.

Michelle: Oh we're going to. We're going to get acapella in here.

Alyssa: Should we do the cups?

Michelle: Yes.

Alyssa: Michelle, you're as excited as I am I take it about the release next week of Pitch Perfect 2?

Michelle: It's true. I do feel we have to explain this to the podcast listeners.

Alyssa: I think it's probably deserving of some background.

Michelle: Pitch Perfect 1 came out. Not very popular in the theaters, but it's a cult classic and I actually did say to my husband, I get to be a fan of a real cult classic for the first time.

Alyssa: Not a Wet Hot American summer fan or anything?

Michelle: Yes, no. None of that, but the second one is coming out next week. I am ready. I was actually working out at the gym listening to the Pitch Perfect 1 soundtrack and the preview for Pitch Perfect 2 came on and I felt like it was just one of those moments where the world comes together.

Alyssa: Where just everything aligns, yes.

Michelle: Exactly. We're very excited, but we also don't sing here mostly because my parents told me I could be anything that I wanted to when I grew up except for a singer.

Alyssa: We dance. We do not sing.

Michelle: We do dance. I almost forgot about that. Maybe one day soon we'll get together and do another music video. Dancing only.

Alyssa: Dancing only.

Michelle: On that note. Ellen let's play parting the Gadfly.

Ellen: On Sunday, John Oliver used a segment of his HBO show Last Week Tonight to criticize standardized testing. Thoughts?

Michelle: I feel like a lot of people have talked about this, but we're going to add onto the bandwagon here and do our take. First, a few facts that I think we must go over.

Alyssa: The facts.

Michelle: John Oliver is funny.

Alyssa: John Oliver is hilarious.

Michelle: He's hilarious, and I knew at some point he would take about education reform. I thought it would either be that all the failing schools in cities have been failing forever and no matter what the unions want they're still failing. More money, [crosstalk 00:02:31].

Alyssa: They could have cited out school closure report in that case.

Michelle: That would have made my day.

Alyssa: I could have gone home.

Michelle: I mean, if John Oliver cites a Fordham study I'm going home or it was going to be standardized testing unfortunately.

Alyssa: Standardized testing it was.

Michelle: Here are a few things, school videos music videos are strange. I mean I know we just talked about our music videos, but I was a little freaked out and I know you guys.

Alyssa: Yes, would you like me to tell that.

Michelle: I would.

Alyssa: When I was teaching I had kindergartners and we had to go to the test prep rally just like everyone else to let the kids know that this exciting thing was in their future, which when you're five is like half of your lifetime away literally, but it was coming down the pike. We got there and the song that they made up, I think it was to Black and Yellow. The eighth graders were in charge. It was spring of 2012. It was an entirely different time. It was just so much that we ended up having to leave because some of the questions I was getting from the five year olds led me to realize this was not something I wanted to discuss with their parent's on the phone later that night. We actually had to leave our test prep rally before they got to the dancing teachers part, but I heard that happened.

Michelle: All right, so I'm just going to say the school music videos are a little weird.

Alyssa: They are, yes.

Michelle: Pearson and other testing companies they have been a problem forever. Everyone in the Ed Reform world knows this. Robert has been right on the drumbeat and I think the talking pineapple example shows-

Alyssa: That has been around for a long time.

Michelle: Has it? I'd never heard of it.

Alyssa: I think so. It's been definitely at least a year.

Michelle: I mean, Robert has been talking and writing and opining and many other things about how you have to have reading passages that are based on information that all kids have access to and that's why they should be knowledge based. Oliver's French kid impression is my favorite thing, period.

Alyssa: I mean most of his impressions are my favorite thing, period, but that one was something definitely very special.

Michelle: My big critique of the segment is that he strings together a lot of different things-

Alyssa: So many strange arguments-

Michelle: That aren't necessarily connected. We've got Common Core. We've got the assessments linked. We've got NTLB. We've got Pearson and other testing companies. We've got teacher evaluation.

Alyssa: All in the same chain of effect.

Michelle: What do you think he got right, and what did he get wrong?

Alyssa: I think he definitely pointed out a lot of problems with implementation and things that if you've been in the ed reform space you've know about of a long time. I noticed he didn't say ... He made a comment about the CCSS logo, but he never said that-

Michelle: Which will never be looked at the same way again.

Alyssa: Yes, but he never said this idea of common high standards is bad. I think it fact he said it was in theory a good idea, but the devil's always in the details, and when tests and evaluations and assessments are not measuring what the kids need to know and not measuring it well then we have problems. We've talked a lot about whether or not testing should be used in teachers evaluations. That's been something that we've been discussing for a very long time and so I think he was generally not wrong about a lot of things I just don't think he strung it together in a very effective way, and whenever comedians take on an issue that I care about and I know a lot about I'm like I spend my all my day doing education reform and then they come out with these out-of-left-field to me opinions, I wonder if he was also wrong on the NCAA and all these other issues.

Michelle: That would be the biggest crisis if he was wrong on college basketball.

Alyssa: What if all these other things that I've listened to him on and be like yeah you know I've agreed. He did a great segment last year. It’s probably his segment that I think about the most. Whether or not all these scholarship dollars from like the Miss America Beauty Pageants are actually reaching students. We'll get to there. Then he made what I felt are really great points and then to me it always calls into question how much should we be using no comedians for our news, and it's something that I think our generation in particular does quite a bit of.

Michelle: I'm just the practical person who says, yes John Oliver got a lot of this wrong and yes some people don't like that comedians are the ones delivering news, but that is also the reality. We, people who are interested in policy no matter if its education or anything else have to be cognizant of this.

Alyssa: Yes. He points out that we have ... and there are things that we're aware of, but there are things that need to be fixed and there are things that we need to work on. We're working on them.

Michelle: Sadly, we can't spend the entire pod cast or our entire day talking about John Oliver.

Alyssa: Much as we would like.

Michelle: Let's go to question number two. Ellen?

Ellen: A recent New York Times article argues that the place of birth significantly effects lifetime earnings. Are you convinced and if so what does it mean for education?

Alyssa: This was kind of a follow-up based on Raj Chetty's earlier research and he came out with another report looking at just the effects of place on upward mobility for students. He found some really interesting results. I thought there are obviously some neighborhoods where kids have much better outcomes than in other neighborhoods. He also found that neighborhoods have a much bigger impact on young boys than they do on young girls, which I thought was a very interesting finding.

Michelle: On that finding, Baltimore of course is pointed out as one of places where it is the hardest to get out of poverty. What I found interesting there is a few months ago for work I read the "Long Shadow" which followed 800 kids in Baltimore over 20 or 30 years I forget now. What it found was that the black children did not do as well as the white children. The people who fared the best were white men and then white women and then black men and actually black women fared the worst because they were often ... They didn't have a partner that could help them economically

Alyssa: Trust and help them out.

Michelle: Then they often had children that they had to take care of and so they suffered the most. I found that it was interesting that this study ... I don't think that it contradicts. It's just a different-

Alyssa: Prism. Yes. I did find essentially the findings came down to look there are like five things, low segregation, lower inequality, better schools, lower crime, and higher rates of marriage and long-term partnership that do lead to an area creating upward mobility for its students and having an impact on rich kids in the area and having an impact on the poor kids in the area and they're not necessarily the area that we think. Fairfax county did really, really well on the findings. I will point out that my home county where I was born, DuPage County Illinois had the best rates of any county in the study so [mic drop 00:09:30].

Michelle: Really.

Alyssa: Really, I just did that.

Michelle: Okay. On that note, no. I think the study is super fascinating, and props to Up Shot for displaying it-

Alyssa: Covering it so well.

Michelle: In such a facilitating way, and I think a way that people spent more time looking at the info-graphic and reading the article than they otherwise might. Props to them. Nothing in here is that surprising. One of the things that was in my mind was we hear over and over again how voters are segregating themselves, and I just think that across issues housing, ed reform, whatever it's not a good idea when different people whatever those differences are, are not living together, not communicating or never running into each other. I think that is how we are going to run into more and more of these problems and these issues.

Andy Smarick emailed about this to me and I just feel that he should get a little bit of credit. What he said was that these are really tricky results and new findings, but what turns out is that good schools, married parents, small income gaps are all good. Something for all political stripes to like. He has a point there, but I also think it's going to be really difficult to change this reality.

Alyssa: Behaviors, and housing patterns, and it's a hard road to reverse.

Michelle: Absolutely. Okay on that note, Ellen question number three.

Ellen: A new Education Next article argues that better charter schools and career in technical education would improve education in rural America. Do you agree?

Michelle: Well before I go there, I'm going to assume that really everyone saw the John Oliver clip, and a lot of people probably saw the Upshot article and this research. I'm going to guess that this one people might have missed. Read this article. It's highly recommended.

Alyssa: Highly recommended.

Michelle: Rural education I think is not only critical and falling behind, but it's not addressed by ed reform and given the stats that the article mentioned are sobering and worth mentioning. One-fifth of students live in rural areas, and we can't just ignore one-fifth of our students. One in four rural kids live in poverty, and of the fifty counties with the highest child poverty rates, forty-eight of them are rural. Don't ask me which of the two are urban because I didn't look it up. We need to stop ... I think this is the perfect argument that we can't have one size fits all. That we do need local because what is easy in urban America to fix or to have a solution for doesn't translate to the rural. You're from a rural place.

Alyssa: Yes, I'm from rural America. Real America. Whatever we want to call it. Yes, I grew up after I moved out of DuPage county I grew up and spent most of my childhood in a small town in Iowa, and a lot of the problems that we have been able to fix at scale in large cities are not problems that we are able to fix necessarily in smaller areas. I did Teach for America and when I was asked which cities I would like to go to D.C. was my first choice for a lot of reasons, and I didn't preference anything in rural America because I didn't necessarily want to live in a rural area.

Michelle: Even education aside, had you even not done the TFA route you'd live in an urban area. You were not going to stay in Iowa.

Alyssa: Yes, and I mean he talks, Stan Fishman the author of the article, talks a lot about the rural brain drain, and when you're from a rural area and you're doing well in school and you're taking advantage of opportunities and you have good grades and you have parents who want you to do well and succeed in life it's very hard for your parents to say, please come back to this town even they've been there, even if they have this life here because they look around and even if you know you live where I live like Minneapolis and Chicago are not that far away and they have such a plethora of opportunities. It kind of perpetuates this cycle. There was a really great book a couple of years ago called, "Hollowing out the Middle" that really addressed that and that really resonated with my experiences growing up in rural America.

You know there are these scale issues and capacity issues and how do you not only ... And talent issues ... And how do you not only just give kids the good education, but how do you support teachers? Things like digital learning definitely do hold a lot of promise. Online charter schools. When I was in ninth grade I was not impressed with the US history course that I was taking and the teacher actually told my mother she could probably do well in a college class. I teach in the college. My mom's like okay I think maybe then we need to get her into a harder class, but there wasn't one so we found like an AP online academy and I took that.

Michelle: Not to now tell your entire childhood on the podcast, but your senior year you also took almost all online courses.

Alyssa: Yes, I was taking about ... I was taking two classes in the school. I was then also taking bio 2 because I didn't want to take physics because I was scared. I'm sorry STEM. Then I was taking everything else online to earn some cred with colleges that I was applying to not even the college credit, but just showing that I was a competitive applicant.

Michelle: I think that this article really lays out the issues and one of the most shocking things in the article is how the two federal grant programs that are sort of either targeted or heavily applied to by rural areas don't really even help the rural areas. They don't address all of these issues and-

Alyssa: Applying for a grant is hard work and if they don't have that capacity.

Michelle: Do you know something about that?

Alyssa: I can talk a little bit about that, but that's for another time.

Michelle: Even when I was active with the DC Young Education professionals in DC, which is obviously an urban thing. The blog post that got that got the most attention. The blog post that lead to re-posting other places were all about rural education and what do we do. How can we have charter schools when even your public school could be many, many miles away. I think we would be wise, for the whole ed reform movement to really pay attention to rural education for two reason. One being way more important than the other. The first, these kids. Then many steps behind that at least a thousand is many of the politicians who do not support ed reform or charter school or choice are rural legislators of both parties because they don't see our current reforms that are being presented as helpful to their constituencies and if we want to make change happen we A have to make sure that all kids have options and I'm not referring to choice in this instance I'm saying ed reforms, and B that they can actually help these kids.

Alyssa: I think that really making sure that whatever options we are presenting align not only for the kids who do want to like me leave and go to college two-year or four-year, but then also for the kids who want to stay and maybe have a career. Like that's something that the rural areas are really well positioned to address and we do have to for their own sake and for their economies sake to create viable partnerships so those economies can continue to regenerate.

Michelle: Absolutely. Okay that's all the time we have for parting the Gadfly. Thank you Ellen. Up next is everyone's favorite Amber's research minute.

Welcome to the show David.

David: Glad to be here Michelle.

Michelle: Notice I did not say Amber's name. Filling in for Amber today is David Griffith. It's his first time on the podcast.

Alyssa: Very first podcast.

Michelle: Welcome.

David: Thank you.

Michelle: We still call it Amber's research minute even though you're covering it.

David: That's okay.

Michelle: Before we get to research, which may or may not be important. Are you a Pitch Perfect fan?

Alyssa: Most important question you'll be asked all week.

David: Um, I am. Guilty.

Michelle: Yes.

Alyssa: Good.

Michelle: I knew you fit into Fordham.

David: I'm excited for the sequel too.

Alyssa: There was somebody on staff they sent out a little email when the trailer came out. Somebody emailed me back, I'm sorry I really don't get it. He or she shall remain nameless, but-

Michelle: Victoria Sears?

Alyssa: Actually, yes. I wasn't going to throw her under a bus, but if you're putting her there I'll just-

Michelle: She's actually is a singer so.

Alyssa: She does acapella or did acapella.

Michelle: That aside, David what do you have for us today?

David: Okay, thanks Michelle. Today, we have a new report from the Institute of Education of Sciences entitled, "Public School Teacher Attrition and Mobility in the First Five Years" which was prepared by Lucinda Gray and Soheyla Taie of Westat and Isaiah O’Rear of the National Center for Education Statistics. The report presents new data from a national survey of teachers which is part of something called, The Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study which is exactly what it sounds like. A longitudinal study of public school teachers who began teaching sometime between 2007-2008 and 2011-2012. What do these new data reveal about teacher mobility and attrition?

Well, there are a lot of findings, but let's just talk about a few that stand out. First, during their second year seventy-four percent of beginning teachers taught in the same school as the previous year, sixteen percent taught in a different school and ten percent were not teaching at all. By year five, seventeen percent of teachers had left teaching. Second, the percentage of beginning teachers who continued to teach after the first year varied by first year salary level. Surprise, surprise. For example, ninety-seven percent of beginning teachers whose first year base salary was $40,000 or more were still teaching in year two of the study whereas only eighty-seven percent of those with a first year salary less than $40,000 taught for a second year.

Third, teachers who started teaching with a master's degree weren't anymore likely to to continue teaching than teachers who started with just a bachelors degree. Fourth, beginning teachers were more likely to continue teaching if there were assigned a first year mentor. Finally, the percentage of teachers who left the profession who did so involuntarily ranged from twenty percent to thirty-six percent depending on the year. Similarly of the teachers who switched schools between their first and second years, twenty-one percent did so involuntary. however, among the teachers who switched schools between their fourth and fifth years, forty percent switched involuntarily.

So what should be make of all of this? Well the report confirms several things that we already know. Many, many beginning teachers leave the school they are working at in their first five years either because they moved to a new school or because they leave the profession entirely. Most teachers who leave the profession do so voluntarily because they're dissatisfied. If we want to keep more of these teachers this study suggests there are a couple of ways to do this.

We could pay them more or we could assign them mentors in their first year of teaching, which seems like common sense given that more than half of the teachers who leave the profession do so after their first year. However, making teachers get a master's degree before they start teaching isn't likely to help. Finally, one statistic that stood out to me was that forty percent of fifth year teachers who changed schools did so involuntarily. I think it's worth asking how many of these folks are good teachers who were laid off and how many are bad teachers who are just being shuffled from one school to another, but unfortunately this report doesn't tell us that.

Michelle: Wow, there's a lot to unpack there.

David: Yes.

Michelle: I can see Alyssa scribbling notes.

Alyssa: I’m scribbling my notes trying to catch all these numbers.

Michelle: Alyssa, what's your big takeaway as a former teacher? You switched in your teaching career.

Alyssa: Because of the earthquake my school closed, but I was kept within the same charter network. My administration changed. My building changed, classroom changed et cetera. Not sure I would necessarily fall into this study, but the finding to me didn't surprise me. It's definitely in line with the kind of research I've seen, my experiences. I have a lot of friends who are now entering or are about to end their fifth year of teaching and why they've left schools or why they transferred schools definitely jives with what these findings are.

David: Yes, I agree. I'm one of those first year teachers who left after one year of teaching. I did not have a mentor. I could definitely have used one.

Alyssa: Oh yes.

Michelle: I think the mentor option seems like one of these reform, like why aren't we doing this?

Alyssa: Low hanging fruit.

Michelle: Low hanging fruit. In critical, in fact it doesn't matter what you're doing professionally teaching or not. First job you've got a lot to learn. I can't imaging the first year of teaching you're alone. You're in a classroom it's very overwhelming no matter what. How can we not have mentors this just seem like ... not low hanging fruit. This is fruit already on the ground.

Alyssa: That easy to pick up

David: I think the last thing I would say is that this study doesn't really highlight or get at the fact that there's a great deal of variation from school to school. These are just macro-level national statistics, but of course we all know that this problem is much, much worse at some school than at others.

Michelle: That's for sure.

Alyssa: Nothing super surprising stands out. I would love to know a little bit more about why teachers are leaving involuntarily if this is them being excessed because of school trends because they are victims of last-in first-out or if this is they're being fired for performance reasons.

David: I suspect that data exists somewhere, but they didn't choose to highlight it.

Michelle: Yes, and i would actually imagine that it's both. Right? I image they are just saying all teachers who left the classroom fit into the study. It could be budgetary issues. It could be low attendance or low number of students per grade. All of that. Who knows, but David excellent “Amber's research minute.”

David: Thank you so much.

Alyssa: You survived the two of us.

David: I survived both of you yes. As I do every day.

Michelle: Ouch.

Alyssa: Well.

David: Okay later guys.

Michelle: And that's all the time we have for this week’s Gadfly show. Till next week.

Alyssa: I'm Alyssa Schwenk.

Michelle: And I'm Michelle Learner for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute signing off.

Report release event for School Closures and Student Achievement study. Held in Columbus on April 28, 2015. Dr. Stephane Lavertu of the Ohio State University presented the findings and a distinguished panel discussed the implications. Panelists: Dr. Deven Carlson (University of Oklahoma, co-researcher), The Honorable Nan Whaley (Mayor of Dayton), Tracie Craft (Black Alliance for Educational Options), Stephanie Groce (former member Columbus City Schools Board of Education), Piet van Lier (Cleveland Transformation Alliance). Moderator: Chad Aldis (Fordham's VP for Ohio Policy and Advocacy).

Jack Jennings was the most influential education policy staffer on the Democratic side of Congress—probably on both sides—for the past half century. He served on the House Education Committee team for some twenty-seven years, then founded and led a well-regarded quasi-think tank called the Center on Education Policy, which continues to issue useful studies.

His new book, timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, is forceful, opinionated, informative, and sometimes quite wrong. (A simple example: He several times attaches my own stint in the Education Department to the wrong president. More importantly, he misstates Richard Nixon’s K–12 proposals and incorrectly describes their handling by Congress.) As Andy Rotherham says on the back cover, “If you agree with everything in this book, you probably didn’t read it closely.”

But there’s much useful history and perceptive analysis here, as well as some pie-in-the-sky recommendations for the future. Particularly interesting to me was how Jennings traced the onset of federal involvement with results-based accountability to the 1988 Title I amendments shaped by Committee Chairman Augustus Hawkins. Those revisions, he writes, “marked a change in attitude among congressional leaders, characterized by increased demands on educators to show academic results as a consequence of receiving federal aid. These leaders no longer believed…that the problem was simply a lack of money. Rather, the belief was growing that schools receiving federal funds should demonstrate that their students were making greater academic progress.”

This is an important addition to the usual account, which leaps from A Nation at Risk in 1983 to the Charlottesville summit in 1990, then to Goals 2000 and IASA four years later.

Jennings acknowledges that these ever-greater demands for results and tighter federal strings were products not just of worrisome education mediocrity, but also decades of cumulative evidence that simply handing out money via programs like Title I wasn’t accomplishing much. He deserves credit for not glossing over such failings, as well as credit for some keen insights into what does and doesn’t work in the federal education policy sphere.

But he does not, in my view, deserve credit for the suite of federal policies he proposes for the future, which comprises a radical increase in spending (to be financed from—where else?—cutting defense and homeland security), a major tightening of the screws on states to force them to make all the changes that Jennings believes would benefit kids, and, finally, either a Supreme Court decision or constitutional amendment to turn educational equity (and funding) into a federal obligation. Opinions will differ as to whether any of this has merit in the abstract. But I can’t picture any scenario under which it would actually happen for as far into the future as I can peer.

SOURCE: Jack Jennings, Presidents, Congress, and the Public Schools: The Politics of Education Reform (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2015).

ACT’s new report is based on a survey it administered to graduating high school seniors who took its college entrance exam, a cohort that now comprises 57 percent of the nation’s graduates. The report analyzes data on the self-reported career interests of nearly 1.85 million students, compared to those who took the ACT in the previous four years; it focuses particularly on those who expressed an interest in education as a profession. This includes survey respondents who planned to major in administration/student services, general teacher education, the teaching of special populations (e.g., early childhood, special education), and the teaching of specific subject areas like math or a foreign language.

The researchers found that between 2010 and 2015, the total number of graduates who planned to work in education decreased more than 16 percent—even though the number of ACT test takers rose 18 percent. Similarly, the percentage of all test takers planning to walk that career path decreased from 7 percent in 2010 to 5 percent in 2016. These students also achieve lower ACT scores than the national average in math, science, and reading—something that was also true in 2010. And the cohort is less diverse than some might prefer: 72 percent of those indicating interest in education were white, which was 16 percentage points higher than the proportion of all test takers.

All in all, it’s a grim snapshot. The individuals who will teach our kids in the future should outperform the national average, not the other way around. When will we heed the call to reform the teaching profession?

SOURCE: “The Condition of Future Educators 2014,” ACT, Inc. (April 2015).

A new report from the Institute of Education Sciences presents new data from a national survey of teachers, which is part of a longitudinal study of public school teachers who began teaching sometime between the school years 2007–2008 and 2011–2012. Of the many findings, six stand out.

So what should we make of all this? Well, the study confirms several things that we already know: Many beginning teachers leave the school they are working at either because they move to a new school or because they leave the profession entirely, and most teachers who leave the profession do so voluntarily (because they’re dissatisfied).

If we want to retain more of these teachers, the study suggests that there are a couple ways to go about it. We could pay them more, or we could assign them mentors in their first year of teaching (which seems like common sense given that more than half of the teachers who leave the profession do so after their first year).

Finally, one statistic that stood out to me was that 40 percent of fifth-year teachers who changed schools did so involuntarily. I think it’s worth asking how many of these folks are good teachers who were laid off and how many are bad teachers who are just being shuffled from one school to another. Unfortunately, this report doesn’t tell us that.

SOURCE: Lucinda Gray, Soheyla Taie, and Isaiah O’Rear, “Public School Teacher Attrition and Mobility in the First Five Years: Results From the First Through Fifth Waves of the 2007–08 Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (April 2015).