Is the Friedrichs case an “existential threat” to the teachers' unions?

A Supreme Court defeat in the Friedrichs case would likely weaken unions—not end them. Michael J. Petrilli and Dara Zeehandelaar, Ph.D.

A Supreme Court defeat in the Friedrichs case would likely weaken unions—not end them. Michael J. Petrilli and Dara Zeehandelaar, Ph.D.

As you’ve probably heard by now, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear the Friedrichs vs. California case next year, giving it a chance to strike down union “agency fees” as unconstitutional abridgements of teachers’ First Amendment rights. (Read up on the case with some great posts from Joshua Dunn, Mike Antonucci, Stephen Sawchuk, and Andy Rotherham.)

Using these data, we ranked the relative strength of state-level teachers’ unions in the fifty states and Washington, D.C.

When we published the study, our measure of union strength included whether agency fees were legal or not as a part of the “scope-of-bargaining” area. We remove that variable from the calculation of strength below. Comparing strength to “right to work” status shows that union strength is clearly correlated with whether unions can collect agency fees. (All data are as of 2012.) Eighteen of the twenty strongest-union states allow the collection of agency fees; most of the twenty states where unions are weakest prohibit the practice, though there are a handful of exceptions (Washington, D.C., New Mexico, and Missouri, for example).

* Michigan and Wisconsin passed right-to-work laws in 2013 and 2015, respectively. These rankings were calculated in 2012.

Note: States in yellow prohibit the collection of agency fees.

It’s not hard to understand why agency fees are important; they allow unions to collect revenue from all teachers, not just union members, which can be used in turn to fund a variety of activities. However, it’s clear that unions in right-to-work states are still able to amass resources and exert authority using other channels of influence.

Alabama, for example, prohibits agency fees and is firmly in the anti-labor, socially conservative South, yet its union (as of 2012, at least) was the most politically active in the nation. Alabama had a high unionization rate, and therefore generated a significant amount of revenue per teacher through dues alone. Teachers’ unions in other right-to-work states, such as North Dakota, Nevada, Nebraska, and Iowa, have also managed to hold on to a significant degree of power.

So will a defeat in the Friedrichs case weaken teachers’ unions, especially in blue states like California, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Illinois? No doubt. But don’t consign them to the ash heap of history quite yet. Expect unions nationwide to spend the next twelve months studying up on Alabama and similar states to learn how they too can hold on to power in a post-Friedrichs world.

As I’ve previously written too many times to recall, for all its iconic status, the Head Start program has grave shortcomings. Although generously financed and decently targeted at needy, low-income preschoolers, it’s failed dismally at early childhood education. Additionally, because it’s run directly from Washington, it’s all but impossible for states to integrate into their own preschool and K–12 programs.

I could go on at length (and often do.) But you should also check out these earlier critiques, both by me and by the likes of Brookings’s Russ Whitehurst and AEI’s Katherine Stevens.

The reason this topic is again timely is because the Department of Health and Human Services recently released a massive set of proposed regulations designed to overhaul Head Start. These are summarized by Sara Mead, with her own distinctive spin.

What to make of them? Yin and yang.

On the upside: A mere seven years after Congress mandated this kind of rethinking, HHS is finally taking seriously the need to put educational content into the country’s largest early childhood program. These regulations would clap actual academic standards and curricular obligations onto the hundreds of Head Start contractors that answer directly to Uncle Sam. Head Start could begin to move—with much grunting and prevaricating to be expected from the contractors, as there has been from the executive branch—from its primordial function as a “child development” program (with no lasting effect on participants’ subsequent educational achievement) toward the kindergarten readiness program that it has long resisted becoming.

This is, to my eye, much the most important element of the regulatory shift. It’s worth actually quoting from the proposed regulations (if you want to see for yourself, track down Subpart C, particularly sections 1302.30, .31, and .32.):

Center-based and family child care programs must implement developmentally appropriate research-based early childhood curriculum…that is based on scientifically valid research and has standardized training procedures and curriculum materials to support implementation [and] is aligned with the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework and, as appropriate, state early learning and development standards; and includes an organized developmental scope and sequence and is sufficiently content-rich within the…Framework to promote measurable progress toward development outlined in such Framework.

Wow: “research-based curriculum”; “scientifically valid”; “possibly aligned with state standards”; “content-rich”; “measurable progress.” All great, and arguably revolutionary. (It’s also important to note that they’re not prescribing any specific curriculum. Operators can choose. If it were my Head Start center, though, I’d need about three seconds to reach for the Core Knowledge preschool sequence.)

This is what Head Start needs. But the proposed overhaul contains trouble, too. It’s a spectacular example of heavy-handed federal regulation, replete with both dubious concepts (“dosage levels” for preschool instruction, which appears to mean program intensity and duration) and bad ideas (making it harder for Head Start centers to shed disruptive kids). All of which follows inexorably from the fact that Head Start would remain a direct-from-Washington contract program, far beyond the purview of states wanting to integrate it into their own preschool efforts and harmonize its curriculum with their kindergarten expectations. Observe that Head Start contractors may align their curricula with state standards “if appropriate”—but they won’t be under any obligation to do so, nor are states given any jurisdiction.

To be clear, Head Start has been direct from Washington for half a century and is already heavily regulated. Indeed, Mead suggests that the new regulations are more coherent and a bit less burdensome than the tangle of red tape that has accumulated over the decades.

Still, it’s hard to think about this without considering Charles Murray’s recent report that the Code of Federal Regulations now runs to some 175,000 pages, and that all this federal overreach has been bad for America in various ways. Head Start is a sizable example of sound impulses gone missing into the jungles of governmental extravagance and bureaucracy.

The HHS-led overhaul may also collide with a slow-moving initiative by the House Education Committee to rewrite the Head Start legislation. Given the composition of that group, it’s fair to speculate that any such legislative revision will give states much greater say in how the program operates in the future.

Certainly Head Start needs a change in direction, and the (ridiculously belated) reforms proposed by HHS are a good first step. Kids might actually learn things that would prepare them to succeed in kindergarten and beyond. The enduring question is whether a massive new set of federal regulations is the best way to effect the needed overhaul, particularly when de-federalizing it is half the change that’s most needed.

ESEA reauthorization, the teachers’ union SCOTUS case, whether character matters, and the effectiveness of first-grade math instruction.

Amber's Research Minute

Michelle: Hello this is your host Michelle Lerner of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net. Now please join me in welcoming my co-host, the Carli Lloyd of education reform, Robert Pondiscio.

Robert: Goal!!!

Michelle: You have to say that three times I believe?

Robert: I think so.

Michelle: So that was one.

Robert: You're lucky you got that. What a game, right?

Michelle: What a game.

Robert: I was in a sports bar in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which I didn't even realize this at the time, six of the women are UNC grads so the place was packed and it was loud. It was so much fun. My daughter, who was an indifferent teenager, said, "I've never felt more American."

Michelle: Awesome. I loved it. I was at home with my husband watching the game and I was like, "This is awesome." I was also following Twitter because I'm slightly addicted and there was some good commentary. I enjoyed it was fun, it made me remember the days back in 1999, 1998, I forget ...

Robert: '99.

Michelle: '99. Mia Hamm. I was a little girl then.

Robert: Back when you were in middle school?

Michelle: Yeah, back when this was like ... Changing my world and here we are back. I love it, super inspiring, great to see women represent the U.S. and win.

Robert: You're speaking of the 99ers, there was a great piece I just saw this morning ... Sorry, we're supposed to talk about education, not sports.

Michelle: Wait, is that we do?

Robert: Something like that.

Michelle: Something like that.

Robert: It was ... I'm drawing a blank on her name, Julie Foudy I think, from the '99 team, started an email chain among all the '99 players, the 1999 players about in real time while they were watching the game, it's on ESPN. Read it, it's fabulous.

Michelle: That's awesome. I will definitely check that out. In the mean time, let's get to part in the Gadfly, welcoming our newest Gadfly reader, Clara Allen.

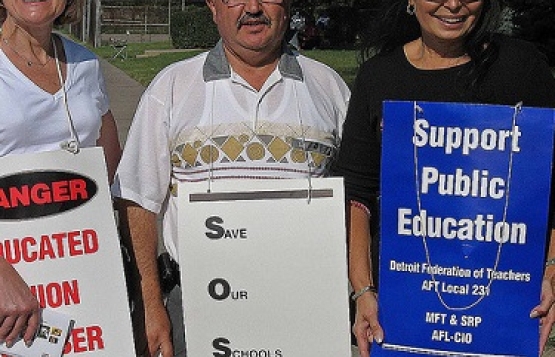

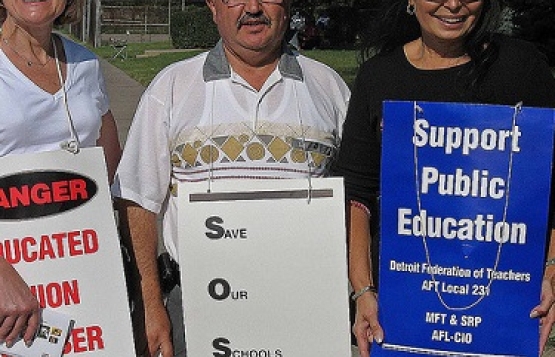

Clara: The upcoming Supreme Court case about mandatory union dues threatens to weaken teacher unions. Are they doomed if the court strikes down these fees?

Michelle: No. To take it a step back, what is this? The Supreme Court, which has been oh so active in the handing down rulings recently ...

Robert: And oh so not conservative by the way.

Michelle: True.

Robert: Just saying.

Michelle: They're going to take up this case that looks at agency fees and whether they are unconstitutional in regards to teachers' 1st Amendment rights. Teachers have the right to not join unions in several states. In non-right-to-work states, agency fees can be deducted from paychecks of teachers not in a union for non-political activity but rather for representative activity, so these includes collective bargaining agreements.

Robert: Right but the case turns on how you interpret non-political activities.

Michelle: Exactly.

Robert: Perhaps there's no such thing if you're a union.

Michelle: That's what many people believe. Back in 2012, slightly before my time here at Fordham, we did a study of looking at the power of teachers' unions in all fifty states. We did look at agency fees, they were a part of the measure of scope of bargaining, so not in the political activity measure. We found that a lot of states ... That there was the ability to collect agency fees is correlated with union strength but there are key exceptions.

Robert: Sure.

Michelle: Alabama being number one there, North Dakota, Nevada, Nebraska and Iowa. Is this constitutional? I have no idea, I'm not aware. But if it does get striked down, is the end of unions' power? No, there are workarounds here.

Robert: Right.

Michelle: But I do think this goes along with a trend that unions and not just teachers unions, that we are seeing smaller and smaller numbers, a lot of people have been reporting on this, so I don't know which way the Supreme Court is going to rule. What do you think?

Robert: I think the conventional wisdom is that they were looking for an excuse to take this case on, so the assumption is that they'll strike it down but what I do not know about the Supreme Court and its processes would fill volumes. Where's Brandon right where we need him?

Michelle: I think he's downstairs working on the Gadfly.

Robert: I'm sure he'll have something to say about this, so stay tuned.

Michelle: Stay tuned. All right, question number two ...

Clara: The Senate this week started a lengthy debate about ESEA. What should we expect?

Robert: A bill! Expect a bill!

Michelle: We have a bill. The question is do we have a law?

Robert: Touché. Thank you. OK. You've just shown me up and I'm supposed to be a civics guy. Good one.

Michelle: The Senate's debating this, exciting, that's not the real news here. The real news is that the House Rules Committee is looking at this. That suggests that they have the votes for this to go to the floor in the House and pass the House. You wouldn't bring something, well they already brought it to the floor once, but it was yanked. You wouldn't send something to the floor unless you are confident you have the votes.

Robert: Our long national nightmare is over.

Michelle: No because you still have to get it past the House, which if they bring it to the Rules, I think they probably have the votes, has to pass the Senate, has to be conferenced, which means if it's going to get through conference it has to move to the left so that they can keep Senate Democrats. Then it has to be signed into law.

There's a huge long hurdle here and you still have the political factors. Civil rights groups aren't happy with the accountability, tea partiers want to get rid of the high-stakes testing here, Andy Smarick had a really great piece.

Robert: I was just going to ask you if you read that.

Michelle: I did. Really great piece in National Review, giving a historical look of why we did what we did in No Child Left Behind and his point is the following: Yes, there was probably too many strings attached on the accountability in No Child Left Behind ...

Robert: Yep. Too much federal overreach.

Michelle: We cannot do the pendulum swings that are so sloppy and everywhere in that reform. We have got to have a middle-of-the-road. We cannot go back to the days where we are simply writing checks and we don't know what happened to them and we don't know how students are doing. We have to keep with accountability. Let's move slightly, let's not go back to the Wild, Wild West.

Robert: You don't go from race-to-the-top to race-to-the-trough.

Michelle: Yeah. Exactly. It's a great piece, I recommend you read it, and it's nice to see someone take a measured view on something. How rare in education reform and in policy.

Robert: Are you saying it's rare for Andy Smarik to take a measured ...

Michelle: You said that.

Robert: She doesn't mean it.

Michelle: I mean anyone in this debate. It's all one side or the other and I think ... If we go back to the union discussion, there's too often unions are the problem, unions are the big thing, no, no, no, unions are saving teaching. Like most issues, there are good and bad to everything. There are drawbacks, there are good policies, you just have to be measured and not make sure you swing to the other side.

Robert: There you go again being all reasonable and stuff.

Michelle: I try occasionally.

Robert: All right.

Michelle: Occasionally.

Robert: What's next?

Michelle: All right. Clara?

Clara: A recent Brookings Institution book asks whether character matters. Does it?

Robert: Yeah of course it does. First I'm embarrassed to admit that I missed this book, it came out in May and it was just brought to my attention just this week, so my apologies to Richard Reeves, I'm devouring it, it's fascinating.

Of course character matters. Everybody knows this. The problem is as a practical matter, what do you do about this in schools? A couple of the essays in this book that are particularly strong. James Hackman has the first one, and he lays out the debate and says, "Of course character skills matter at least as much as cognitive skills. We know that. What else do we know? We know that character is shaped early, not unlike literacy in that regard ..."

The question and I don't want to be unkind but I'm not sure the book ever quite wrestles fully with this issue is if we know that that non-cognitive skills can be shaped and they matter what's the appropriate agenda for public policy? That's a very tricky question to answer. One of the strongest ones if you care about education, there's a gentleman named Dominick Randolph who is the head of the Riverdale School in the Bronx, New York, near where I live, who points out that this is a heavy lift for schools and those are my words, not his, but one, character skills are very difficult to define ... We don't have an SAT so to speak, for character. There's not enough evidence to support how you shape it, in other words, what would the intervention look like ...

Then he makes the leap and he loses me honestly about this where he says that we need to truly come up with intervention standards if you like about character. I read this and I immediately thought, "OK. Good luck with that, Dr. Randolph."

Michelle: Take a look at Common Core and see if you want to go down that ... A triangle is a three-sided shape. That is not complicated.

Robert: Let's agree on that ...

Michelle: How we talk about morals and character in school? Oh gosh.

Robert: Can you imagine Common Core character standards. At that point I'm going to become a barley farmer before I take that on. Having said that, I don't want to be dismissive, obviously this matters a lot, at the risk of taking an obvious approach here, if you really want to get serious about this, I think all roads lead to choice. You really can't impose a character education regime or curriculum in a non-choice environment. That's my take, that's not the book's, but as I read it, I kept thinking that over and over again. This is really an argument for choice.

Michelle: Right. I don't think we can get everyone to agree that x characteristics are good to see in kids, that we need to cultivate and therefore all schools are going to do that.

Robert: You could but they'd be so benign ...

Michelle: Exactly.

Robert: As to be meaningless. Take turns, share. Nobody's going to disagree with that.

Michelle: Exactly.

Robert: Once you start to get into these so-called performance characteristics, like grit and perseverance, the closer you get to these very personal character traits, the more parents and I think not incorrectly so are going to say, "Wait a minute. That's my job."

Michelle: Not to go down Fordham's historical road of studies but we're going to do it now twice on this podcast ... In 2013 we put out a market research survey of parents on what parents want and it was on two aspects. What should schools do and it turned out all parents really wanted the same things. Good, high standards, which is good for the Common Core and then we did student characteristics on the other side of the questions and a lot of the parents agreed on things but we did see these niches of some folks wanted a strong civics education, some people were strivers and they really wanted their kids to go to these top-notch colleges, we had test-score hawks, parents who really cared about how their school and their students performed on assessments, we had multiculturalists, parents who really wanted diversity in their school. I think we can build a really strong character in systems of choice, but even then, it's really difficult to teach.

Robert: Absolutely ...

Michelle: Because what do we know that works?

Robert: I'm not an expert on this. My gut tells me it's easier to create the conditions that valorize the character traits that you want than to teach or impart them directly.

Michelle: To me this goes in the bucket of, "You don't join education for an easy job." If you want a, "Oh, we've got the solution, we're just going to do it, go home at 5:00 at night," you're in the wrong profession. I think these issues go to the core of it is really difficult, it is really political and it is really near and dear to people's hearts that we do this and how we do it and that we do it correctly and no one has the answers.

Robert: Can't add to that. I agree with you completely.

Michelle: All right, thank you. Clara, that's all the time we have for part in the Gadfly. Up next is everyone's favorite, Amber's Research Minute.

Michelle: Welcome to the show, Amber

Amber: Thank you, Michelle.

Michelle: So did you watch the best soccer game in all of history?

Amber: I did and I'm not even a soccer person but how exciting was that.

Michelle: Yeah. I think you have to watch the soccer game.

Amber: Yes. You're un-American if you do not watch the World Cup ...

Michelle: Even if for some reason you weren't, once you hear that they scored four goals in the first fifteen minutes ...

Amber: Yes, I was watching with my mother and some other family members and my mom kept saying, "I'm so happy they wear ponytails. I just want them to look feminine," So many of them have ponytails.

Michelle: Wow. I think she might be the only one who said that.

Amber: They do have ponytails.

Michelle: Though I have to say I wasn't a fan of the neon green socks. It's not tied to our colors.

Amber: It's a little much.

Michelle: All right, but it was a good game, nice to see our ladies on top again ...

Amber: Yes.

Michelle: What do you have for us today?

Amber: I have a new study out by Penn State researchers and they examined which type of instructional strategies are most effective with first grade math students. These are kids both with and without mathematical difficulties, which they call MD, I'll tell you how they measure that in a second. They analyze survey responses from roughly 3,600 teachers and data from over 13,000 kindergarten children in the class of 1998-99 in a database known as the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study or ECLS. Most folks are familiar with ECLS. They controlled for students' prior math and reading achievement, family, income and a host of other things. MD by the way, you're wonky about this, was defined as falling in the bottom 15% of the score distribution on the ECLS Kindergarten math test.

Key findings, in first grade classrooms with higher percentages of students with MD or math difficulty, teachers were more likely to use practices not associated with greater math achievement by the students. I wish Robert was here because he'd find this interesting. These non-effective practices included using manipulatives, calculators, movement and music to learn math. They were also non-effective with kids without math difficulties. Some of these progressive teacher strategies that teachers were taught including me, not so effective with these little kids that have math issues, yet more frequent use of teacher directed instructional processes was consistently associated with gains in math achievement of first graders with these difficulties. More specifically, the most effective instructional practice teachers can use with these struggling youngsters is, what do you think?

Michelle: I don't know.

Amber: It is drill and kill as we call it.

Michelle: Checker would be so thrilled.

Amber: It is routine practice and drill. Just going over and over and over ... Lots of chalkboard instruction, traditional textbook instruction and worksheets that go over the math skills and the concepts again were also effective with these kids. For students without math difficulties, same thing. The teacher directed instruction was really effective for them, was also associated with the gains, but for the kids that didn't struggle with math, some of the student-centered instructional activities was also pretty effective for them and they defined that as things like working on a problem that has several solutions, peer tutoring, doing real life math problems which you hear about a lot ... Those things actually work with the kids who don't struggle. The kids who don't struggle, they can do both the teacher-directed and the student-centered and excel in both ways.

Michelle: That makes sense.

Amber: Researchers concluded at the end, this is troubling because the kids that need this type of instruction the most aren't getting it.

Michelle: Yeah, that is troubling. I have to say, as you were talking, I remember back to the day when I got a cassette that was a math multiplying table rap, so I could learn my multiplication table.

Amber: Wow. Did it help you?

Michelle: It might've helped me. I was good at math, I have to say, so I didn't have any struggles, but math is boring so I can understand that teachers want to make it interesting but the problem with math is it's built on itself. If you don't get a concept, you're just done. You're not going to get Algebra I, you're not going to get Algebra II, you're not going to get Calculus ...

Amber: You are making me thing of Mr. Van Orden, my Algebra II teacher, and every day, I hated the class, but every day he got up there for forty-five straight minutes and worked math problems for us on the board, just worked them, one after another after another ... Then at the very end we'd come up and maybe work one and he would walk us through it. That's all we did the whole entire time was work math problems on the board every day for us and I learned so much ... Same thing, it's not your favorite teacher that's the one who teaches you the most often.

Michelle: Yeah.

Amber: It's the one that you just dread going into their classroom, but honestly I did great in that class, just because he showed us, teacher-directed instruction, every single day.

Michelle: It's just required for this subject, I'm thinking I took an economics class last semester for a graduate school so here I am, hopefully never taking math again and here I am back in micro and I'm taking derivatives and re-remembering calculus from very long ago. The professor pointed out that you first learn these skills when you're taking the slope of a line back in fifth grade. Everything builds upon ourselves.

I do think we could do more to make connections to the real world. I remember being in Algebra I and Geometry and Calculus and all these classes ... What does this even mean and if someone had stopped and said, "This is how it is actually used in economics or in building bridges and all of these things and a lot with our computer technology now," I think you could get more people interested but in the end, you got to know how to do it.

Amber: Yes.

Michelle: If you don't know how to take a slope of a line, you're just done.

Amber: Just to say, maybe music, it can't hurt.

Michelle: I still remember the cassette tape.

Amber: We get into all this learning style stuff where the kids move their body in the direction of the math problem, I don't know ... Teachers think of this crazy stuff with kinesthetic learning, anyway ... Bottom line is, in this study, it didn't work for the kids who just need some instruction.

Michelle: You know, I'm not surprised by that unfortunately. All right, thanks so much, Amber.

Amber: You're welcome.

Michelle: That's all the time we have for this week's Gadfly Show. Till next week.

Robert: I'm Robert Pondiscio

Michelle: And I'm Michelle Lerner for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, signing off.

So-called “turnaround school districts,” inspired by Louisiana’s Recovery School District and its near-clone in Tennessee, have been gathering steam, with policymakers calling for them in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and other states scattered from coast to coast. But just how promising are these state-run districts as a strategy to bring about governance reform and school renewal? What lessons can we take away from those districts with the most experience? Can their most effective features be replicated in other states? Should they be? What are ideal conditions for success? And why has Michigan’s version of this reform struggled so?

The title of this slim, engaging book of essays tees up a question about which there is very little disagreement. Of course character matters. “Character skills matter at least as much as cognitive skills,” writes Nobel laureate James Heckman in the lead essay, summarizing the literature. “If anything, character matters more.” Since cognitive and non-cognitive skills can be shaped and changed, particularly in early childhood, he writes, “this suggests new and productive avenues for public policy.” It may indeed. But the journey from good idea to good policy is a minefield for both parties, as Third Way policy analyst Lanae Erickson Hatalsky notes in her essay. If Democrats talk about character, “it runs the risk of sounding like apostasy, blaming poor children for their own situation in life and chiding them to simply have more grit and pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” (Likewise, the Left dares not invoke the miasma of family structure.) Character talk may feel more at home in Republican talking points, but it carries the risk of foot-in-mouth disease, “setting the stage for politicians to inadvertently say something that sounds patronizing to the poor, demeaning to single women, or offensive to African Americans (or all three).” Just so.

Educators will be particularly interested in the essay contributed by Dominic A.A. Randolph, the head of the elite Riverdale Country School in New York City. He is almost certainly correct that countries like Singapore, which dramatically outperform us in math, may do so precisely because “strengths like self-control and perseverance may be cultivated more intentionally, and more successfully, in cultures other than ours.” But his solution, a “comprehensive international effort in institutions and in governments to develop intellectual, character and community standards of growth that can be embedded in the ‘curricula’ of schools, universities, workplaces” will surely bring gales of laughter from those battered and bruised in fights over Common Core. As Randolph himself acknowledges, “While measuring math skills seems a viable objective public pursuit, measuring character seems a personal, subjective, and private endeavor.”

Non-cognitive character skills may “lie at the very center of human flourishing,” in Heckman’s phrase, but one of the volume’s few disappointments is its failure to include an essay on school choice as a means of giving educators permission to focus on character development. When parents are voting with their feet or their tuition dollars, an explicit effort to build character can be one more reason to choose a school like Randolph’s or KIPP, which has for years worshipped at the altar of “grit” as the key to student success. For K–12 education at large, the pitfalls of education for character development are surely insurmountable. Brookings’s Stuart Butler observes that discussions of character and virtue tend to fall on critics’ ears “as a moral judgment about poor people.” He prefers the term “culture,” which connotes “a web of influences in a neighborhood.” (Psst: “Culture” is even more of a fighting word than “character.”) UCLA’s Mike Rose sums up the difficulty of making character development an explicit, measurable goal of public education anytime soon. “As a matter of public policy, it would be counterproductive, and ultimately cruel, to focus on individual characteristics without also considering the economic and social terrain on which those characteristics play out,” he writes. Allow me to translate: The “fix schools” versus “fix poverty” debate, as it pertained to cognitive skills, has been exhausting and unsatisfying. In non-cognitive domains, it’s unthinkable. Don’t expect Common Core character standards any time soon.

SOURCE: Richard V. Reeves, ed., Does Character Matter?: Essays on Opportunity and the American Dream (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2015).

Career and technical education (CTE) is the reform de jour. And the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB), created following the Second World War to improve social and economic life for sixteen southern states, has taken notice. In an April report, the commission outlines the career and technical pathways that can help job seekers find employment and improve struggling economies.

Advanced credentials and CTE programs could be a game-changer in the South. Among the sixteen SREB states, at least a quarter of adults fail to complete any form of education after high school. In West Virginia and Arkansas, those numbers are as high as 40 percent and 34 percent respectively. An additional 20 percent of adults in each of the states complete some postsecondary work but receive no credential. And this lack of credentialing doesn’t just hurt working class adults. The report notes that “even youth born to middle-income families are as likely to move down the economic ladder as they are to move up.”

To reverse this dismal trend, the report calls for increasing the percentage of students who leave high school academically prepared for college and career to 80 percent (authors repeatedly call for higher and more rigorous standards, though they never mention “Common Core” by name) and doubling the proportion of adults who earn a postsecondary credential by age twenty-five.

The report lays out eight action items for states and districts to adopt in order to strengthen the connection between high schools and postsecondary institutions. They include creating relevant career pathways, providing CTE teachers with professional development to meet technical standards, and restructuring underperforming schools around rigorous career pathways. These are all, of course, noble pursuits in struggling economies. But whether states can turn this framework into implementable policy remains to be seen.

SOURCE: “Credentials for All: An Imperative for SREB States,” Southern Regional Education Board (April 2015).

When thinking about innovation in America, our thoughts typically turn to tech-driven creative capitals like New York City and San Francisco. Yet this report from the Rural Opportunities Consortium, which argues that rural education is primed for innovation, demonstrates that change can also be bred outside of cities.

Author Terry Ryan, president of the Idaho Charter School Network and a former member of the Thomas B. Fordham team, focuses on three main advancements that rural schools have adopted: expanding school choice through charter schools, introducing new online technologies, and increasing collaboration between charter schools and local districts. All three give rural schools and districts greater autonomy and freedom to experiment with new programs and concepts.

To prove that rural areas can successfully implement these changes, Ryan profiles districts that have instituted them. For example, the Dublin City School District in southeast Georgia has followed in the footsteps of big cities like New Orleans and Washington, D.C. by embracing charter-driven school choice. Dublin’s increased administrative flexibility has allowed them to pilot new ideas, develop more direct lines of accountability, and ultimately raise high school graduation rates. Another example, the Vail School District in Arizona, created Beyond Textbooks, an online tool that serves schools and districts in Arizona, Wyoming, and Idaho by facilitating the exchange of lesson plans and resources among its roughly ten thousand members. It offers partner schools digital access to Vail’s fully standards-aligned curriculum and lesson materials, providing them with a low-cost alternative to purchasing traditional textbooks. And Idaho’s Upper Carmen Charter School has partnered with two neighboring school districts to share blended learning and early literacy programs that would be too difficult or costly to maintain independently. Sharing services has been a critical factor in the schools’ ability to provide a broad range of education choices to their students.

Using these case studies as models, the report recommends that policymakers break down the barriers to continued innovation by endorsing more school choice, relaxing administrative restrictions, and giving rural districts and charters the freedom to test new technologies. "Large chunks of the country’s interior are aging and seeing their younger residents migrate to population centers for employment," Terry notes. "The health of a rural community is intimately connected to the quality and availability of jobs, and to the effectiveness of the local schools....Business needs strong schools to prepare its workforce, and education needs business to employ its graduates." Quite right. And this report can serve as a worthy guide.

SOURCE: Terry Ryan, “Rural innovators in education: How can we build on what they are doing?,” Rural Opportunities Consortium of Idaho (May 2015).