The bright children left behind

We mustn’t let other countries surpass us in producing tomorrow’s inventors, entrepreneurs, artists, and scientists. Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Brandon L. Wright

We mustn’t let other countries surpass us in producing tomorrow’s inventors, entrepreneurs, artists, and scientists. Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Brandon L. Wright

A great problem in U.S. education is that gifted students are rarely pushed to achieve their full potential. It is no secret that American students overall lag their international peers. Among the thirty-four countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development whose students took the PISA exams in 2012, the United States ranked seventeenth in reading, twentieth in science, and twenty-seventh in math.

Less well known is how few young Americans—particularly the poor and minorities—reach the top ranks on such measures. The PISA test breaks students into six levels of math literacy, and only 9 percent of American fifteen-year-olds reached the top two tiers. Compare that with 16 percent in Canada, 17 percent in Germany, and 40 percent in Singapore.

Among the handful of American high-achievers, eight times as many kids come from the top socioeconomic quartile as from the bottom. That ratio is four to one in Canada, five to one in Australia, and three to one in Singapore.

What has gone wrong? Thanks to No Child Left Behind and its antecedents, U.S. education policy for decades has focused on boosting weak students to minimum proficiency while neglecting the children who have already cleared that low bar. When parents of “gifted” youngsters complained, they were accused of elitism. It is rich that today’s policies purport to advance equality, yet harm the smartest kids from disadvantaged circumstances.

High achievers were taken more seriously during the Sputnik era. The National Association for Gifted Children was founded in 1954, the same year as the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. As the country concerned itself with educational equity, Carnegie Corporation president (and future U.S. secretary of health, education, and welfare) John W. Gardner posed a provocative question in his seminal 1961 book, Excellence: Can We Be Equal and Excellent Too?

The year 1983 brought “A Nation at Risk,” the celebrated report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, which declared that poor schools were contributing to national weakness: “Our once unchallenged pre-eminence in commerce, industry, science, and technological innovation is being overtaken by competitors throughout the world.” Five years later, Congress passed the sole federal program to focus specifically on gifted students, which intermittently provides a modest $9 million a year for them.

Poor test scores show that gifted American children still aren’t reaching the heights they are capable of. How do other nations achieve better results? We set out to examine eleven of them—four in Asia, four in Europe, and three that speak English—for our book, Failing Our Brightest Kids: The Global Challenge of Educating High-Ability Students.

Unsurprisingly, we found that culture, values, and attitudes matter a great deal. Parents in Korea, Japan, and Taiwan push their kids to excel and often pay for outside tutors and cram schools. So costly has this become, and so taxing for parents whose children come home at night exhausted, that families are apt to have only a single child—unwittingly contributing to their nations’ demographic crashes.

Finland is a different story. Equity and inclusion are the bywords, and teachers are supposed to “differentiate” instruction to meet the unique needs of every child. Elitism is taboo, and competition frowned upon. Yet Helsinki boasts an underground of specialized elementary schools that parents jockey to get their children into. Most Finnish high schools practice selective admission, including more than fifty that, as a local education expert told us, “can just as well be called schools for the gifted and talented.”

In Germany and Switzerland too, the high schools (“gymnasiums”) that prepare students for university are mostly selective. A handful also have intensive tracks with extra courses for uncommonly able youngsters.

Western Australia, like Singapore, screens all schoolchildren in third or fourth grade to see which of them show particular academic promise. Those who excel can choose to enter specialized classrooms or after-school enrichment programs. Both countries also boast super-selective public high schools akin to Boston Latin School or the Bronx High School of Science.

Both Ontario and Taiwan treat gifted children as eligible for “special education,” much like disabled students. This gives them access to additional resources, but these students are also squashed under cumbersome procedures. For instance, a committee must review their progress annually, and they may generally not transfer out of the school that the bureaucracy assigns them to.

What lessons can the United States take from this research on how to raise the academic ceiling while also lifting the floor? States could screen all their students and offer top scorers extra challenges. They could encourage smart kids to accelerate through school or even allow every child to move through the curriculum at his own pace. Why must every eleven-year-old be in fifth grade? Technology eases such individualization, but this change would also require agile teachers and major revisions to academic standards, curricula, and tests that now assume every child should progress through one grade each year. Schools would have to ensure that extracurricular and social activities remain more or less based on age. But liberating fast learners to surge forward academically would do them—and society—a world of good.

If and when Congress finishes reauthorizing No Child Left Behind, it should encourage states to track and report not only progress by low-achievers, but also academic gains by gifted students (as Ohio already does). Lawmakers should direct the Education Department to gather far better data on strong students than are available today.

For their part, states and school districts need to offer better options for high-ability pupils. One possibility would be schools that admit on the basis of academic potential, the way that New York’s Stuyvesant High School does. This model should be extended to middle and elementary school. Gifted poor children, in particular, need that kind of academic support from the start.

If we cannot bring ourselves to push smart kids as far as they can go, we will watch and eventually weep as other countries surpass us in producing tomorrow’s inventors, entrepreneurs, artists, and scientists.

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared in a slightly different form in the Wall Street Journal.

What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all its children. – John Dewey

The intuitive appeal of this oft-quoted maxim is obvious. It speaks to the conviction that all of the children in a community or a country are “our kids” and that we should want the very best for them just as we do for our own flesh and blood.

Taken literally, however, it is also problematic, for it equates “sameness” with “equity.” That’s an error in part because what “the best and wisest parents” want varies—some seek traditional schools, others favor progressive ones, etc.

But it’s also a mistake because children’s needs vary. Kids growing up in poverty and fragile families, and dysfunctional communities need a whole lot more than kids living with affluence and stability. And when it comes to their schools, poor kids may need something a whole lot different. That’s why I’m a big fan of No Excuses charter schools, which are showing great promise for low-income children—even if they might not be a good fit for many of their upper-middle class peers.

All of that’s been on my mind of late as I ponder the plight of the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) outside of Washington, D.C. (My second-grade son is one of its 155,000 students.)

MCPS, to its credit, is a system that’s long been publicly committed to equity. Especially under the decade-long tenure of Jerry Weast, its hard-charging superintendent throughout the 2000s, the district, its schools, and its board were obsessed with addressing achievement gaps. It poured additional resources into its poorest schools—aimed particularly at pre-school programs and smaller classes—earning it plaudits from reform organizations and equity hawks alike.

Yet beyond these targeted investments, the MCPS strategy has been one of Deweyesque sameness. Schools throughout the County use the same curriculum and enjoy the same quality of teachers—teachers who participate in the same professional development experiences.

What’s not the same, however, are the outcomes.

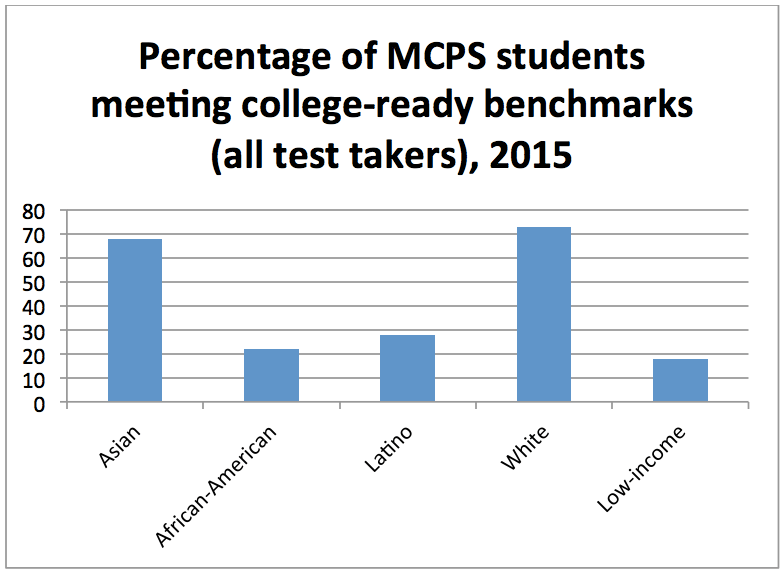

Let’s allow the pictures to speak for themselves. The chart below shows the percentage of MCPS students who met the district's “college ready” benchmark on either the SAT or ACT this past year. Note that the denominator here represents those students who took at least one of those college-entrance exams.

Source: Table C1, Montgomery County Public Schools, Office of Shared Accountability, SAT Participation and Performance and the Attainment of College Readiness Benchmark Scores for the Class of 2015.

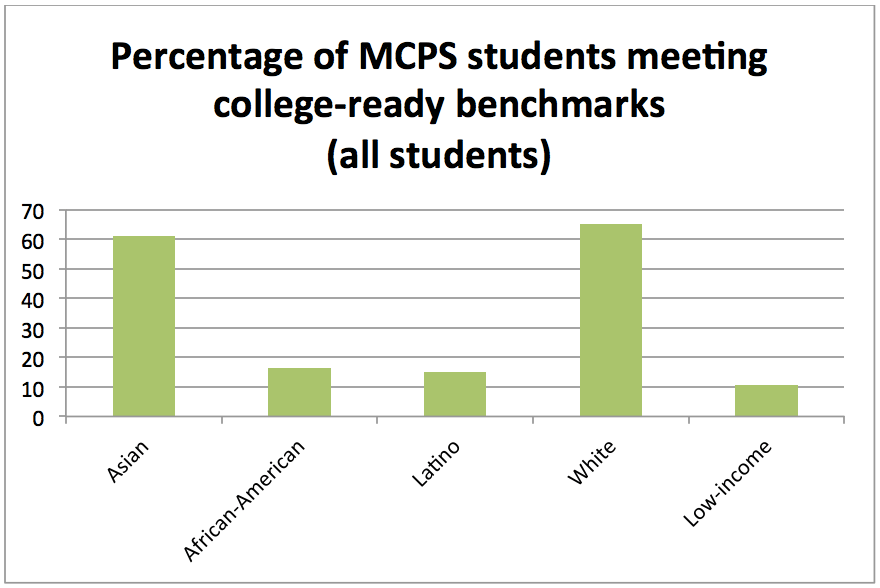

Those proportions—and gaps—are devastating enough. But not all MCPS students take the SAT or ACT; in fact, participation rates vary significantly between racial and income groups. Now let’s look at the proportions using all students as the denominator. (I’m assuming here that everyone who skipped the tests would likely fail to reach “college readiness” benchmarks. That’s probably mostly right, though not totally right. Keep that in mind.)

Source: Table C1, Montgomery County Public Schools, Office of Shared Accountability, SAT Participation and Performance and the Attainment of College Readiness Benchmark Scores for the Class of 2015.

Yes, you are reading that right. Montgomery County is getting just 11 percent of its low-income students to the college-ready level, and fewer than one in five of its minority students. (Low-income students make up about a third of MCPS’s enrollment.) After all of the efforts of Jerry Weast and Joshua Starr. After spending hundreds of millions of extra dollars on pre-school, smaller classes, and all the rest. Eleven percent.

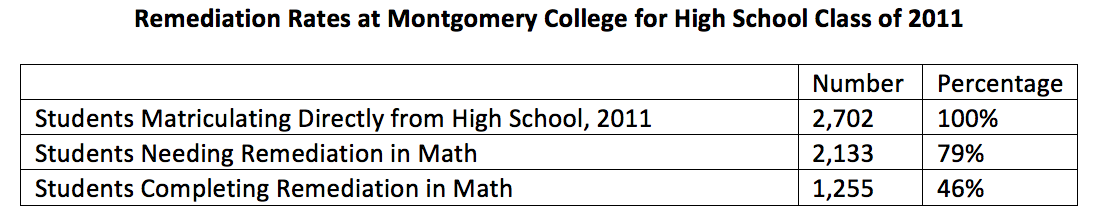

This surely explains the heart-breaking situation at Montgomery College, the county’s enterprising and generally well-regarded community college, where almost 80 percent of students coming straight from high school must take remedial math—and where more than half of students never make it past remediation.

Source: Tables A-13 and A-14, Developmental Education at Montgomery County, Office of Legislative Oversight.

To be sure, “college ready” is a high standard. The SAT, ACT, and NAEP all find that just 30–40 percent of high school graduates nationally meet that mark. And in fairness, MCPS sets an even higher standard for college readiness than the testing organizations do (1650 on the SAT versus 1550, and a 24 on the ACT).

Still, these numbers ought to be causing serious soul-searching on the MCPS school board. They ought to be dominating conversations about who should replace Starr as the next superintendent. They ought to be plastered across the Washington Post’s metro section.

The next superintendent should look at these numbers and develop an urgent and aggressive plan. He or she might start by asking: Is MCPS’s “curriculum 2.0” strong enough? Truly aligned to the Common Core? Might we learn something from the District of Columbia Public Schools and its efforts to create a robust, knowledge-rich curriculum in grades K–12? Might the county get off its high horse and invite D.C.’s best charter schools to set up shop in Langley Park or Wheaton or Gaithersburg? Are we doing enough to provide career- and technical-education opportunities to our young people, especially since we’re not doing enough to get everyone ready for college?

The search committee for the next superintendent might ask themselves: Why not try to poach Kaya Henderson from DCPS? Or Susan Schaeffler from KIPP DC? Or consider experienced reformer Jean-Claude Brizard, who lives just across the line in Northwest, D.C.?

The one thing they—and we—shouldn’t do is remain complacent.

***

Montgomery County deserves credit for making these data public and for its willingness to wrestle with its achievement gaps. That’s more than can be said about many suburban districts. Now it needs to take the next step and acknowledge that its low-income students may need something strikingly different than its affluent children do. It needs to reject “sameness” and strive for real equity instead. That is, of course, if it believes that many more low-income students than 11 percent could be—and should be—ready for college after thirteen years in its highly-lauded schools.

eternalsphere25/iStock/Thinkstock

SOURCE: "School Composition and the Black-White Achievement Gap," U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (September 2015).

Robert : Hello, this is your host Robert Pondiscio of The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, here at The Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net.

Now, please join me in welcoming my co-host making his podcast debut, the Lin-Manuel Miranda of education reform, Kevin Mahnken.

Kevin: Thank you very much Robert, it's nice to be here.

Robert : You say that now.

Kevin: Yeah, we'll see how this goes. I have no experience in any audio format to this point, so it could very well go off the rail very quickly.

Robert : I'm going to count on that. Speaking of Lin-Manuel Miranda, the reason I evoked him, do you know why?

Kevin: Tell my Robert.

Robert : He just was named a MacArthur Genius Grantee, right? Well deserved.

Kevin: Yeah, he has now been officially designated a Genius. That debate has now been squared away. The keepers of our culture have now elevated him to that status, and I appreciate it because I like his work.

Robert : I like his work, I loved Hamilton. If you haven't seen it, see Hamilton. Mortgage or keep your children's lunch money, save whatever you have to, go see it. It's great.

Did you look at the list of the other ... because you're not on it this year, neither am I. Again.

Kevin: No, I got it in 2012. They don't double up. It's considered wasteful. No, you see the top line winners who would be Miranda and I think this year it's Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Robert : Correct.

Kevin: Then ...

Robert : Twenty-two people I've never heard of.

Kevin: Yeah, as we've discussed, fairly obscure but brilliant people who have dedicated their lives advancing some cause that they're now being remunerated for.

Robert : Handsomely.

Kevin: Yeah, to the tune of, what like, $700,000?

Robert : A lot of money and they continue doing it and we can continue not having heard of them.

Kevin: Yeah indeed, and in the case of Miranda, it means maybe he will seek it to consecrate some other unjustly ignored founding father.

Robert : Benjamin Rush, The Musical.

Kevin: Yeah. Dudley Wigglesworth, The Sage of Concord. I would love to see it.

Robert : Good. Get on that Mr. Miranda.

All right let's play, Pardon The Gadfly. Clara, take it away.

Clara: The achievement gap in suburban school districts does not get much attention. Why should stake holders be concerned that districts, like Montgomery County, are getting only 11% of their low income students college ready?

Robert : What a fascinating ... Did you read the speech by our good friend, brother Mike Petrilli?

Kevin: I did. Yes. I read all his work.

Robert : Okay, of course you do.

Kevin: I prefer his early work.

Robert : Pre 2012.

Kevin: Yeah.

Robert : He sends his sons to the Montgomery County Schools and he came up with this remarkable piece of data, that shows a well regarded suburban school district. When you look at it by sub groups, only 11% of the kids of color, low income kids of color, in Montgomery County are college ready as determined by SAT and ACT scores. I was kind of surprised by that.

How about you?

Kevin: I was surprised of the two figures that he shows in his piece that's the more striking one of kids who have taken, I think it's the ACT/SAT, you see higher figures for black and Latinos. It's somewhere a little bit closer to 20%, but of course you want to take a broader numbers.

It is surprise, what makes them stark I think, is that you've got these huge scat's of white and Asian students who are being deemed college ready, according to these metrics, and the gap is therefore much, much wider and it cuts against what we would normally think of a somewhat affluent district like Montgomery County.

Robert : The point is a good one I think, and one that I think we think of ourselves as education reformers, we tend to focus on urban schools, right? Some of the same population that we focus on are in these suburban schools, and guess what? They're doing just as badly here or there as they are in the intercity. It's kind of fascinating.

He starts out, Mike's piece, I was going to call it my favorite quote from John Dewey but I mean that archly or ironically, this business about, "What the best and why does this parent want, so should every parent want for his/her child and I think less is un-levelly and undemocratic."

I've referred to that before, you see this all the time where good ideas, and I'm making air quotes around good ideas, that work pedagogically for affluent kids we say, "Hey it worked so well in the Upper East Side." Let's take it to the inner city where it crashes and burns. This is the same phenomena within a district. What's working well for affluent kids in a place like Montgomery County, it may not be working so well for low income kids. Mike's point, and I think its a good one is, do we need to rethink the instruction program to differentiate it more to give kids what they need just not what they think what we think they should have?

Kevin: Even access to, in a case of low income kids, resources that have been earmarked for then but have not been delivered. You may have seen, there was a new report released by essentially a small think tank associated with the county, research that says something like, "50 million out of about 128 million in funds from the state for low income students didn't go directly to programs benefiting low income students. It went to general operating budgets."

That may be. That's certainty legal and since the district saw a huge amount of funding cuts on the wake of the recession, the cut a lot of positions, that may even be the right thing to do but it makes you think you're seeing these fast gaps in the income levels. Perhaps if low income kids had the resources that they were meant to have in the first place, would it be different?

Robert : Good question. I'd love to see this same data run done for suburban school districts across the county I think we would learn quite a lot.

Number 2 Clara.

Clara: In the book Split Screen Strategy, Ted Kolderie suggests that some students could benefit from graduating much earlier. Do you think rethinking the high school graduation age is a healthy or productive way to rethink the traditional education model?

Robert : Boy, oh boy, oh boy. I'm going to say something I've probably said a thousand times on this podcast which is, "It's complicated." I know that this is a very, "Which vain of ore to mine." A lot of people think, "We should have competency based classes. Why are having this lock, step, march, k-12, 13 grades and then you graduate. Let's let students proceed at their own pace, etc, etc."

I get it. I'm sympathetic to it. The only counter argument that I would like to hear more of is, kind of the cultural orientation of school. I'm guessing all of us at this table, all of us listening to this, had that classic k-12 experience and yes we can see ways to improve it, but that's just the way we do school. Am I being fussy by just saying, "Well that's just the way we do school?" There's some intrinsic value to that. Let's be very, very careful about messing with that?

Kevin: I guess this makes you the Edmund Burke of the educational reform.

Robert : That's right.

Kevin: Educational reform has been pointed out by a contributor like Andy Smarick. It is sort of inherently seemingly bias toward change. Toward shacking up the status-quo. I think that's probably to it's benefit. The status-quo exists for a reason, of course.

In the case of Kolderie's book, there is something persuasive about this case to me. He makes sort of a broader claim, and perhaps a indefensible claim, it's quoted in our review in this weeks Gadfly by Kate Stringer, that he reckons that with the number, I'm paraphrasing, with the number of restrictions that are in place, basically on the freedoms and the freedoms of movement and opportunity on adolescents, that they are the most discriminate against segment of people in our society.

Robert : Come on, that's a little bit of over statement.

Kevin: Yeah, he's making sweeping claims. I see some truth in it. By 16 it seems to me, at least some high school students ought to be able to choose their own path.

Robert : Sure.

Kevin: If that own path includes seeking employment outside of school. In high school I didn't even have the option of seeking part time employment.

Robert : Okay, I did. Name a fast food restaurant? I worked there.

Kevin: How long did you stay, though? That's the question.

Robert : Longer than I should have perhaps. Maybe the job is still open.

I don't want to over argue the case because I think there really is some wisdom, and he's Ted Kolderie, and who am I? I just get very, very nervous when we suggest just blowing up these models that are not merely academic. I'm bias here, my daughter's an athlete okay for example, it had been a very great big part of her schooling. I was involved in theatrical productions when I was in high school.

We have schools for things other than academics. There's civic institutions. There are cultural places. They're athletic institutions for our kids. You can't pull one of these levers without disrupting some of the other ones. Do I think that there should be more high school models that allow the kinds of kids Ted is referring to to be better served? Of course. Do I want to upset the entire the apple cart and say, "Let's change the way we do high school in America?" I'm not quite there yet.

Speaking of which, this is kind of related. Number 3 Clara.

Clara: Dartmouth economist have suggested that the boom of the fracking industry has increased high school dropout rates. Are students being forced to chose between work and school?

Robert : I don't know if they're being forced to choose, but this data that's kinda fascinating says that they are choosing. Guess which one is losing?

Kevin: It's school.

Robert : Right. It's kind of interesting. I know 1 or 2 young people who actually went out to North Dakota a few summer ago to work in the fracking fields and made a boat load of money, and they were real happy about that. This piece of research, I believe was from Dartmouth, suggested I think there was a 1 1/2% or 2% decline in graduation rates because they're linking this with job opportunities in fracking, which is kind of fascinating.

Kevin: Yeah. It's actually even more stark than that. I think I saw 1.5% to 2.5% increase in the drop out rate for each percentage point increase in employment in the oil and natural gas fields. That's pretty striking.

Robert : It sure is.

Kevin: It could very well be that this is another area that's impacted by the recession. Jobs are hard to come by and you have extraordinarily high paying jobs for extraordinarily low skilled workers.

Robert : Yup.

Kevin: Perhaps it's only logical that they should seek employment outside of school, but there's a down side to that because these fields, which arise basically out of nowhere, often end up turn in to ghosts towns. Since it's peak in December of 2014, the national oil and gas industry has shed 8% of it's jobs.

Robert : Peek fracking.

Kevin: Peek fracking. We may still see yet another spike at some point, but right now we got depressed fuel prices and that's leading to a lot of these places being shut down. While it makes perhaps short term sense, I think this case probably argues against my point from the previous segment.

Robert : Pick one Kevin.

Kevin: Yeah, exactly. Let a 17 year old choose and he may choose $15 an hour in a fracking facility, but that could not be a good decision for long.

Robert : Aaron Churchill, our colleague, reviewed this report for The Gadfly and makes the point I think is the good and obvious and correct one, which is students should not have to choose. This perhaps reinforces Kolderie's point in the previous segment. If we want kids struggling, there's an interest in seeing them being upwardly mobile so that $15 hour job, yeah it's hard to say no to that, and let's applaud the initiative. That's great, but we don't want them dropping out of school. Is there a way, is there an educational school model that will allow them to do both. That will allow them to take advantage of short term economic opportunities, while continuing to matriculate. I don't know what that model is but maybe Ted Kolderie could get to work on that for us.

Kevin: More over, I think it's just as a final point it's worth pointing out, that fracking is not necessary solely to blame for this. You see this in a lot of parts of the country where all of a sudden, employment opportunities blossom for folks without a lot of job skills. Construction would be a great example of the housing boom. If a 16 year old is sitting board in pre-calculus and he knows that he can be making oodles of money, literally 10's of dollars an hour working a low skill job, then they're going to be doing it regardless of whether it's fracking or another field. It's probably something we should keep in mind.

Robert : Yeah, exactly. Fracking is the current phenomenon, but there will be other opportunities like this. If you want to rethink high school, that's not a bad way to start is by looking at the economic opportunities that exist in making it possible for kids to take advantage of both their academic trajectory and the short term opportunities. Why not? Makes all the sense in the world.

That's all the time we have for Pardon The Gadfly, and now it's time for Amber's Research Minute.

How are you doing today Amber?

Amber: Doing great. Just tired of the rain already and this thing has turned into a hurricane I hear.

Robert : Really?

Amber: Yeah. Category 1, that's what I heard on the news this morning.

Robert : I did not know that. I was just going to ask you if you made the short list for The MacArthur Genius because Kevin won in 2012, which I didn't know until this morning.

Kevin: This was a couple years ago. It was for my musical about James Otis.

Amber: I did not know that.

Kevin: Yeah.

Amber: They have Geniuses of all different stripes, right? You can be a Genius in all different things, as I recall when I looked at it last time.

Robert : Indigo child theory of genius? We're all Geniuses.

Amber: We're all Geniuses in some way. Yes.

Robert : I get that. I'm revealing myself to be completely unsophisticated with the exception Ta-Nehisi Coates and Lin-Manuel Miranda, there were 22 people I could not have picked out at a police line up.

Amber: Right.

Robert : Not that I expect to.

Amber: Right. They're artists and musicians and thought leaders.

Robert : Right, but nobody from the world of education.

Amber: Philosophers, yes. Right.

Robert : Right, so maybe next year.

Amber: Maybe next year.

Robert : You and me. What do you got for us?

Amber: All right. We got a new study out by NCES called School Composition and The Black-White Achievement Gap. We spend a lot of time talking about this achievement gap, don't we?

Robert : We do indeed.

Amber: Uses data from the 2011 NAEP Grade 8 Math Assessment to examine the black-white achievement gap in light of the make up of the school. Specifically, how does the gap look in schools where the density of black students is high or low, which is simply the percentage again, of black students in a school. They use this density word which is a little off putting to me and maybe I'm just being overly sensitive here, but anyway, we talk about density of the school. That just is code word for how many black kids are in that school. Okay?

Robert : Okay.

Amber: Key findings on average nationally, white students attended schools that were 9% black, while black students attended schools that were 48% black.

Robert : In the averages. Makes you wonder.

Amber: On average nationally.

Robert : Okay.

Amber: No surprise here, but the highest density schools were mostly in the south. Okay, we know that, and in cities. Low density schools were mostly in rural areas. All right, so that's no big surprise.

Robert : Right.

Amber: Three-quarters of of public schools, that about 77%, are the lowest density, meaning 0% to 20% black students and 10% are highest density, which is 60% to 100% black students. Okay. That's all the descriptive stuff.

Then they do another annalists where they control for factors such as social economic status and all these varies school and teacher and student characteristics. Then they apply all of these controls.

Then they find that 1 white student achievement in the highest density categories, I mean highest density schools, did not differ from white student achievement in the lowest density schools. The white student achievement stayed static.

Robert : Regardless of ...

Amber: Relative of whether you're in high density or low density. Yes.

Number 2 for black students overall and especially black males, here we go with our black males again, achievement was lower in the highest density schools then in the lowest density schools. The black male kids had lower achievement in the higher density schools then in the lower density schools. Okay?

Number 3, this is kind of interesting, there were no significant difference between the percentage of black student in a school in achievement for females. Whether the female was black or white, we didn't see statistically significant differences for the females.

Again for the males, the black-white achievement gap was greater in the high density schools by about 25 points of a gap. In the lower density schools to was only 17 points with the gap. One thing to keep in mind, because it's descriptive, it's not causal, is that they can control first off things like family income, teacher credentials and all this other stuff but you still have a self selection bias. Your not going to wipe out that self selection bias no matter how many controls you try to throw in there. What we're saying is, there's something about parental motivation, for instance right, that we just can't measure. We've got to concede that students in these mostly, I'll use the word, "Segregated schools," right if you will, are going to be different then those who are in integrated schools in ways that we can't really measure. Okay?

In the end I was just thinking to myself, the fact remains whatever you think about the study, it's mostly descriptive, it's correlational. We fret a lot about whether schools are segregated or not and what to do about them. I think this study is light on the answer to that because it's obvious a very complicated problem.

Robert : Sure.

Amber: It's good descriptive information but I think that they really short change the fact that these kids are still different in fundamental ways that we can't measure.

Robert : The answer is, we need to know more?

Amber: Yeah. I think we need to know more and I think that we need to concede that we can talk about these gaps and we can talk about how many black kids are in a school and how that impacts achievement and correlational away, but we can't be real definitive about these differences that we're seeing because we're not able to really figure out how these kids are fundamentally different.

There's something going on here that these models can't capture. I was just saying, let's not die on the toward relative to these research finding's in particular. I think, and you guys know this more then anyone, in the school choice world right? Some of these no excuses schools are being sort of beat up on because they're not caring so much about integration. They're setting up schools in these inner-cities where these kids are and some folks are beating them up for that. I think this kind of research is trying to speak to that problem of what do we still do about these schools where you just don't have a lot of diversity?

Robert : Right. Great question and it's not going to go away anytime soon. Thank you Amber. That's all the time we have for this weeks Gadfly Show. Until next week.

Kevin: I'm Kevin.

Robert : I'm Robert Pondiscio from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, signing off.

Nearly ten years ago, Congress established the Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF). A total $1.8 billion has been disbursed since then by the U.S. Department of Education to districts to accomplish four tasks: overhaul their teacher evaluation systems, create merit pay bonuses based on them, give educators opportunities to take on additional responsibility for more money, and offer professional development to support teachers in their efforts to hit these higher marks.

Under the TIF program, bonuses are supposed to be “substantial, differentiated, challenging to earn, and based solely on educators’ effectiveness.” Since this evaluation shows that 60 percent of teachers received a bonus in a subgroup of districts studied, it’s fair to wonder just how challenging to earn they really were. Moreover, understanding of the program still seems sub-optimal. In the second year of implementation, more teachers understood their eligibility for bonuses and how they were being evaluated than in the first year. “Yet more than one-third [38 percent] of teachers still did not understand they were eligible for a bonus,” the report notes. “And teachers continued to underestimate the potential size of the bonuses, believing that the largest bonuses were only about two-fifths the size of the actual maximum bonuses awarded.”

These disconnects make it hard to know whether or not the program is achieving its main goal of improving student performance, which in any event is rather modest: gains in reading achievement of a single percentile point, and gains in math that were “similar in magnitude but not statistically significant.”

“Full implementation of TIF continues to be a challenge,” the report notes with understatement, “although districts’ implementation from the first to the second year improved somewhat.” While 90 percent of TIF districts were implementing three of the four required components for teachers in year two of the program, only about half were implementing all four. And while the vast majority of participating districts put in place achievement growth measures of effectiveness based on all students in the school, only about two-thirds of districts reported evaluating teachers based on the achievement growth of only the students in their classrooms. Whether this was a deliberate decision or a reflection of the confusion over the program’s aims, it calls into question the entire theory of change underlying the TIF program.

The bottom line is that neither those who favor merit pay nor those who abhor it will find the Mathematica report particularly satisfying. It suggests that merit kinda, sorta might work if teachers understand how it works. The better takeaway might be what’s written between the lines: Want to devise a merit pay program that has a measurable impact on student achievement? Keep it simple, stupid.

SOURCE: Hanley Chiang et al., “Implementation and Impacts of Pay-for-Performance: The 2010 Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF) Grantees After Two Years,” Mathematica Policy Research (September 2015).

In Eastern Ohio and elsewhere across the nation, fracking has had a profound effect on economic activity and labor markets. But has it had an impact on education? According to a new study by Dartmouth economists, the answer is yes: The proliferation of fracking has increased high-school dropout rates— among adolescent males specifically, and not surprisingly. They estimate that each percentage-point increase in local oil and gas employment—an indicator of fracking intensity—increased the dropout rates of teenage males by 1.5–2.5 percentage points.

The analysts identify 553 local labor markets—“commuter zones,” or CZs—in states with fracking activity, including Ohio. For each CZ, they overlay Census data spanning from 2000 to 2013 on employment and high-school dropouts (i.e., 15–18 year olds not enrolled and without a diploma). The study then exploits the “shock” of fracking—it picked up significantly in 2006—while also analyzing the trend in dropouts. Prior to 2006, dropout rates were falling for both males and females; post-2006, dropout rates for males shot up in CZs with greater fracking activity. (Female dropout rates continued to decline.) Using statistical analyses, the researchers tie the increase in male dropout rates directly to the fracking boom.

This study raises important issues about the work-school decisions that some teenagers face. In the case of fracking, a fair number have opted into the full-time labor market—arguably a rational decision, at least in the short-run. (For such teens, attending school represents a considerable opportunity cost in light of decent wages.) But what if jobs in the oil-and-gas fields dry up—what are their options then? Have they sacrificed the longer-term benefits of an education for a short-lived windfall?

Perhaps adolescents shouldn’t have to make a premature choice between school and work. Why can’t they have both? Vocational tracks and specialized schools—like the Utica Shale Academy charter school in CITY, Ohio—offer students an opportunity to gain hands-on experience while earning their diploma. For those with an immediate need of a paycheck, policymakers should consider ways to boost paid apprenticeships or promote part-time employment. However accomplished, young people deserve every opportunity to explore the world of work, without sacrificing academics, during their teenage years.

Source: Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ayushi Narayan, Who Needs a Fracking Education? The Educational Response to Low-Skill Biased Technological Change (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2015).

There’s a classic puzzle that requires connecting a square of nine dots with four lines; the problem appears impossible until the solver realizes that she can extend the lines outside the box. Ted Kolderie does just that in his new book arguing for a bevy of bold yet sensible reforms that would upend today’s education model.

Some suggestions are not so revelatory, such as increasing student motivation and personalized learning. But as Kolderie continues, he makes his way to recommendations that would shake up everything from age-based student grouping to how we think about achievement and teacher leadership. To be sure, none of his ideas are meant for every district in every state. “‘America’ does not have schools…Massachusetts has schools, Texas has schools, California has schools,” Kolderie writes. Each state, he believes, should adopt and its own reforms to fit its unique needs.

Kolderie’s most compelling argument is that U.S. schools require too many years of attendance. Some young people are ready for responsibility sooner than our system allows. So by requiring everyone to stay in school until age eighteen, we’re preventing millions of people from reaching their full potential. “The restrictions built into the institution of adolescence have made young people arguably the most-discriminated-against class of people in our society,” Kolderie says, adding that these discriminations lead to disruptive behavior and unmotivated teens. As recently as the early twentieth century, nearly half of all sixteen-year-olds worked full-time, while the other half attended school. And even today, there are young people who do amazing things in spite of these misplaced restrictions: a thirteen-year-old who sailed around the world, a fifteen-year-old who developed an algorithm for diagnosing bladder cancer, and teen twins who started a computer software business. Kolderie also notes that reducing the number of years of mandatory schooling would save states billions of dollars—never a bad thing.

Above all, Kolderie wants to break free of the confines of the age-level, one-room traditional classroom that he insists cannot possibly juggle the needs of twenty-five students on its own. He acknowledges that such a shift could take a long time and would require changing how society perceives youth, how we allocate resources, and how we structure school days. Specifically, schools should start providing students with career training, internships, and apprenticeships. As Fordham has argued, a four-year degree isn’t the only path to professional success. There are faster, less-expensive ways to gainful employment. Let’s embrace those too.

SOURCE: Ted Kolderie, The Split Screen Strategy: How to Turn Education Into a Self-Improving System (Minnesota: Beaver’s Pond Press Inc., 2015).