The new ESEA, in a single table

The action is moving to the state level. It’s about time. Michael J. Petrilli

The action is moving to the state level. It’s about time. Michael J. Petrilli

As first reported by Alyson Klein at Education Week’s Politics K–12 blog, Capitol Hill staff reached an agreement last week on the much-belated reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. The conference committee is expected to meet today to give its assent (or, conceivably, to tweak the agreement further). Final language should be available soon after Thanksgiving, with votes in both chambers by mid-December. If all goes as planned, President Obama could sign a new ESEA into law before Christmas.

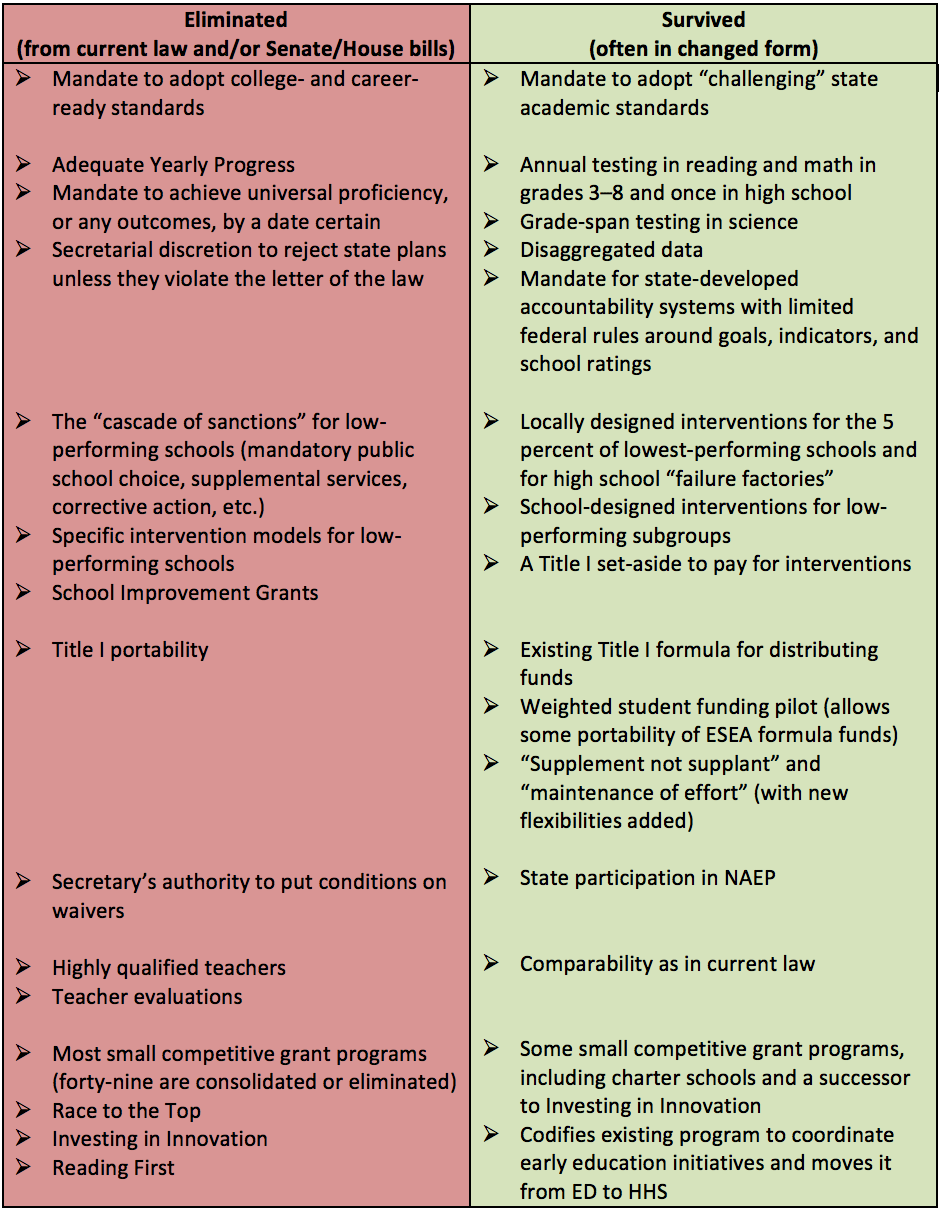

So what’s in the compromise? Here’s what I know, based on Education Week’s reporting and my conversations with Hill staffers. (There are plenty of details that remain elusive.) I’ll display it via a new version of my handy-dandy color-coded table. (Previous editions here, here, here, and here.)

The Staff Agreement Heading into Conference

Note: Some of these provisions aren’t in current law—some were in the stimulus bill (like Race to the Top), some are in Secretary Duncan’s conditional waivers (like teacher evaluations), and some were in one of the bills passed in July (like Title I portability).

There you have it. Readers (and especially Hill staff): Tell me if you think I got anything wrong, and I’ll fix it. And advocates at the state level: Get ready. It’s looking extremely likely that by January, states will find themselves with a whole lot more discretion over their accountability systems, interventions in low-performing schools, teacher evaluations, and much else. The action is finally moving out of Washington. In my view, it’s about time. But as Uncle Ben told Spider-Man, “With great power comes great responsibility.” Let’s make sure the states exercise that responsibility sensibly.

dkfielding/iStock/Thinkstock

The Achilles’ heel of the West, I read not long ago, is that many people struggle to find spiritual meaning in our secular, affluent society. How can we compete with the messianic messages streaming from the Islamic State and other purveyors of dystopian religious fundamentalism?

It made me reflect on my own life. How do I find meaning? Largely from my role as a father, a role I cherish and for which I feel deep gratitude. But ever since I lost faith in the Roman Catholic Church of my upbringing—not long after I nearly succumbed to cancer at age eighteen—much of my life’s meaning has come from my view of myself as an education reformer.

I suspect that I am not alone. We are drawn as humans to heroic quests, and those of us in education reform like to believe that we are engaged in one. We’re not just trying to improve the institution known as the American school; we see ourselves as literally saving lives, rescuing the American Dream, writing the next chapter of the civil rights movement.

When people speak of Arne Duncan with tears in their eyes—explaining earnestly that he has always put kids first—it is because he epitomizes the virtuous self-image of the education reform movement. He has been our Sir Galahad. Now that he’s stepping down, he will always be revered by some as St. Arne.

This near-religious fervor gives the reform movement much of its energy and its moral standing, so it should not be dismissed lightly. To the degree that it helps us continue to strive—for better schools and better policies and better outcomes for kids— it is worthy of celebration.

But there’s a dark side too. Like most religious legends, this one only works well as a struggle between good and evil. So if reformers are on the side of the angels, at least in our own minds, who gets cast as the devil? The unions, which protect incompetent, abusive, or racist teachers? Miserly legislators, who refuse to appropriate the necessary dollars to lift all children up? Well-off parents, who hoard educational opportunities for their own progeny?

Not surprisingly, these groups don’t enjoy being vilified. Nor, in most cases, do they deserve it. They are engaged in their own struggles, see themselves fighting for their own sacred causes, and are busy looking for meaning in their own imperfect lives. They might not totally disagree with reformers about the changes needed in K–12 education, but when we turn them into Judas or Mephistopheles, opportunities for common ground evaporate.

But that’s not all. What if our education challenges aren’t mostly political or moral in nature, but fundamentally technocratic instead? What if our education system is chockablock with people who also want to do right by kids, who also want to close opportunity gaps and rekindle upward mobility, but are working within badly designed systems or with far-from-perfect information? “We know what works, we just need the political will to do it”: That’s the foundational creed of today’s reform movement. But what if the truth is closer to “We are just beginning to learn what works to help poor kids escape poverty, but we still don’t know how to do it at scale”? It doesn’t make for an inspirational slogan, but it might be a better guide to where policy and practice need to go. To his credit, Bill Gates embraced such a humble approach in his big speech a few weeks ago.

In other words, what if the reform movement needs more “science” and less “religion”? More openness to trial and error and a greater commitment to using evidence to guide our decisions?

Consider one example. We know that many students continue to struggle to read by the end of the third grade, and some show ever-weaker comprehension as they move through elementary school and beyond. Cognitive science indicates that the cause is a lack of content knowledge being taught in the early grades. So why aren’t schools beefing up their instruction in social studies and science, or inserting such content into their daily reading blocks? There’s no devil here as far as I can tell–nobody is against getting more science and social studies into schools. But how can we figure out what’s keeping schools from performing better, and then try to find ways to fix it?

Humility is required

It’s been a great joy to be part of the education reform movement for the past twenty years. It has allowed me to form bonds and friendships with many amazing, committed, and super-smart colleagues. I understand why so many young people today—fresh from service in Teach For America or still plugging away in “no excuses” charter schools—want to sign up and join the cause. On the whole, this is a wholesome and worthy path.

But if this is really to be about “the kids” and not just our own search for meaning, we need to be careful not to lapse into morality plays. We need to be particularly mindful not to malign our opponents. And we need to be humble enough to acknowledge the technical challenges in what we’re trying to achieve.

We should also remember that millions of American educators are finding meaning in their lives in a different way—through direct service to children. This is at least as praiseworthy as taking up a great political cause or policy quest, and almost certainly more so. (It certainly appears to be more in line with Pope Francis’s calls for us to take care of the less fortunate around us.)

It’s always been a good idea for us to check our egos at the door. Let’s check our halos there, too.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form at the Hechinger Report.

supansa9/Thinkstock

Why reformers ought to check their halos at the door, ESEA's final stretch, Baltimore's high-achievers, and students' reactions to news of their AP potential. Featuring a guest appearance by the Ingenuity Project's Lisette Morris.

SOURCE: Naihobe Gonzalez, "Information Shocks about Ability and the Decision to Enroll in Advanced Placement: Evidence from the PSAT," Mathematica (October 2015).

Mike: Hello, this is your host Mike Petrilli at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net. Now, please welcome me in joining my special guest co-host, the Kirk Cousins of education policy, Lisette Morris.

Lisette: Hello, Mike.

Mike: So, Lisette is the executive director of The Ingenuity Project in Baltimore. We're going to hear all about that in a little bit, Lisette. The Kirk Cousins thing, it makes sense because here he is, he is a star quarterback now, for the Washington Redskins. We were having a surprisingly good season and yet he was not the starting quarterback at the beginning of the year. So, it's like you're coming out on the scene. You're coming off the bench into the big time. You have been a listener of the Education Gadfly Show for years. Now, here you are on the show itself.

Lisette: Right, and sitting in this incredible little recording studio you have here.

Mike: Thinking, "Wow, I thought it would be more impressive than this."

Lisette: Maybe, I'll go back to the image I had in my head.

Mike: Yeah, exactly. It doesn't really look like NPR. Does it? No.

Lisette: Really fancy.

Mike: Yeah, it doesn't look fancy at all. Well, it's great to have you here.

Lisette: Thank you.

Mike: Lisette and we are going to talk about your work that involves gifted and talented kids. But we are also going to talk about the weeks' news because of course there is a lot happening on that. So, Clara let's play Pardon the Gadfly.

Clara: Lisette, you work with high achieving students in Baltimore through your organization, The Ingenuity Project. What do you think is the most promising method for identifying gifted and talented students?

Mike: Lisette, we should say that this is an issue we care an awful lot about and Checker Finn and Brandon right here have a new book out and they'd struggle with this question that when you start talking about quote gifted kids or gifted and talented kids, huge controversies in who counts. Some people who want that to be a very strict definition, others who say every child is gifted in some way. Those people are probably not parents, just kidding. Or, maybe they are. But what do you think? Where do you come down on this?

Lisette: Wow, this has been an issue of debate in our program for a while. I stepped into this role a year and a half ago. Of course, that was a good opportunity for everybody to kind of revisit this idea of who do we identify.

Mike: What do you guys do? Tell us just a little bit about Ingenuity.

Lisette: Yes, we run a middle school and high school program for particularly STEM subjects. We recruit and identify students. We use multiple measures right now and we're in the process of changing what some of those measures are.

Mike: And this is Baltimore City?

Lisette: Yes, for Baltimore City.

Mike: So, mostly low income and minority kids?

Lisette: Well ...

Mike: Or a mix in Baltimore?

Lisette: Right, a mix. Very much a mix. Our program actually, I think, is probably one of the most integrated areas in the city where you will find students who have many options of going to private schools and sending their kids off because they have financial means. But decide to choose Baltimore City schools and you have students who are the first generation in their family to go to college, all in one learning environment.

Mike: A lot of people say, if you just look at test scores because we have this huge achievement gap, that inevitably, you're going to end up identifying relatively few low income kids or kids of color. Then that just perpetuates the gap in some ways. Yet, we also can see that if you have other ways of screening, there are plenty of low income and minority kids who, if given the chance, could excel in these kinds of programs. How do you find ... what else do you look at if it's not a test score?

Lisette: Our previous model for many of years included a teacher's recommendation. We had an ability and achievement test. We also looked at report card grades. We looked back, just this summer, at five years of our admissions data. Started to really look because we keep many of these students into the high school program. We looked at outcomes in their SAT, GPA, things like that. What we noticed is that there was no correlation between the teacher recommendation and the student's outcome and completion of the program.

Mike: Well, that's interesting because, I think it was just last week, Amber reported on a study where teachers tended to underestimate the talent of poor and minority kids at the high in of the achievement spectrum. That is clearly a big problem. So, that's good. So, you're going to get rid of those teacher recommendations. Sorry teachers, you're out of the picture.

Lisette: We value you're opinion but ...

Mike: But ... No. It's hard to standardize those things, of course as well.

Lisette: The other thing that we found is that the indicators in our admissions process that mostly reflected in the success of students later on, were the assessments that we measuring things that the students were going to do in the future. For example, for our high school program we give an algebra assessment. We're a pretty rigorous math and science program. Students who succeeded already in Algebra 1 had a very strong likelihood of being successful all the way through. So, what you measure and then what you're looking for and you know that they're going to need to do in the program is really important.

Mike: Excellent, okay. Claire, topic number two.

Lisette: Mike, your piece in the Hechinger Report suggested that ed reformers stop casting the debate in terms of good versus evil and that we should check our egos and our halos at the door. How come?

Mike: This is something I've been really struggling with for a long time. Some of this is a little bit of a mea culpa. I, certainly, over the years have been involved in these debates that sometimes get nasty. Calling the teacher unions evil in various ways or coming close to it. Saying, "Oh, they're nothing but these greedy union bosses who are just taking money from their members and stomping on the needs of kids. All that kind of rhetoric which I used to partake in. I guess as I've been in this now, I've gotten older. I'm getting ready to have a midlife crisis or something.

It just has become clear to me that very few people in this debate, if any, are out there for bad reasons or ulterior motives. Everybody is out there trying to make the system work better. A lot of the people that we view as our opponents in education reform are themselves stuck in a system that doesn't work and is broken and they are trying to fix it. So, I think it's just important for us to step back and think in any debate, particularly in America today, with our level of political polarization. It's just always a good idea to refrain from villainizing people that we disagree with.

I also, and Lisette be curious about this, I do think, of course there's a moral component to some of these things and the cause of making our system more fair and equitable. But there is also just a big technocratic challenge. Right? It's just hard to figure out what works, how to scale what works, how to make choices. Something like The Ingenuity Project for example, you have to struggle with these questions in terms of who gets into the program, how to help it be more successful. What are the methods that you use? Some of this comes down to values, and equity, and moral stuff. Some of it just comes down to how do we get good research and then apply it and get better at what we're doing and get better technically at the work at hand.

In other words, what I've been trying to say is it's not just like a religious fervor that we need in education reform, we also need a commitment to science.

Lisette: Yes, so my board is made up of several scientist and researchers from John Hopkins University. I am so honored to work with many of them because sometimes in the midst of what can be sometimes a very emotional and personal debate there are many of my board members that would step back and say let's look at the data. I appreciate that because you are so right that we always continue to have to go back and look at this because it can become very deeply personal for many of us and especially in the world of gifted education.

You got very personal in your article and having children of my own you realize that it is complex and you see the things you fight for, for your own children and then you see the things you fight for, for students who have different experiences and different home lives than our own children do. When we put all these labels on things I think that's when the debate starts to pro-charters, anti-charters, pro this. It does, it starts to polarize in a way that I think what we offer is a solid instructional program whether you want to call it gifted and talented or who you could put in the program. It does get very personal but we continue to go back and look at who's successful in the program to make those decisions.

Mike: More than anything else, I just want to banish from the conversation this phrase that we at least used to hear all the time, "We know what works, we just need the political will to do it." And you say, "Really? Really? No, we need more humility." We don't know what ... Yes, we can go into individual schools that are getting great results. We are learning about how to scale that up. KIPP now has scaled up to 120 schools. That's great! But that's still like 10,000, 20,000 kids. Do we know how to make the system work for 50,000,000 kids? No, and we have a lot yet to learn. Okay, topic number three.

Clara: Rumor has it that congress is closing in on a decision regarding ESEA re-authorization. What are the pros and cons about what we know so far?

Mike: Oh, it's not just a rumor Clara. As we record, the conference committee is getting started. It's pretty exciting. For all the signals is that this thing is pretty much baked. They've got a deal at the staff level. They are having a conference committee. I guess this almost never happened before and their opening comments. People like Barbara Bukowski was like, "I didn't think I was going to get to see another one of these before I left congress or before I died."

This is just ... They were just beside themselves having regular process here in congress. So, that's all very good. Look, we're feeling pretty good about this deal at Fordham. We think it is very much in line with what we've been calling for. Which is, scaling back the federal role, changing the role from being one that's very much heavy on quote accountability, and that's much more focused on quote transparency.

It says we keep the testing. We keep the data. We disaggregate. The state still has to turn all of that into some kind of rating for schools. Get that information out to parents. We think that is an appropriate thing for the federal government to require in return for 10 percent of the money. Which is what they provide but all the important decisions around, how the accountability system works, whether to do teacher evaluations, how to intervene in low performing schools. All of that goes back to the states and we think that's where it should be.

Lisette, do you agree? And you don't have to. It's more fun, frankly, if you disagree. So, even if you do agree, if you could disagree right now, I would really appreciate it.

Lisette: I will disagree on a few areas. I ... Right, do I even go the common core route? I'm like, "Oh, gosh." Having experienced and been a part of the ... from early conversations around common core before it had a label and now watching it in full implementation and for four years, being on the side of working in the district. The conversations that people were having around curriculum were different. They were tough but they were different.

I, no one will ever agree, think that everything in there is perfect. But, I do worry that when we scale back that many different states function at different levels. For the sake of allowing all students to have access to rigorous standards, I do worry that scaling back what type of standards a state uses is going to go back to producing some of the same results we did where you can see states that have very rigorous standards and very rigorous tests.

Mike: So, you are worried that some states will take the opportunity to, for example, ditch the common core or college and career ready standards or go back to their easier tests and their cheaper tests. That's all absolutely something that could happen and that's why now the fight has to shift to the state level. I am, for one, more optimistic that the education reformers ... people that believe in high standards and tougher tests and more transparent, honest information that we will be able to win these fights.

We certainly have more than an infrastructure at the state level than we did 10 years ago. Groups like MarylandCAN and others that wake up every day and try to fight these fights at the state level. So, I'm hopeful. But look, it's also on us. We have to be able to make the case to educators, to parents, to policy makers, that continuing with standards based reform with high standards with testing, with transparency, setting the bar high, all of that is working and that it's important not to back down. If we can't make that argument then shame on us. Right? This is the way democracy works.

Lisette: I was excited to see some of the efforts around accountability and paying more attention to the measuring of high achieving students and advanced students because for too long we have focused on the proficient and advanced and clustered that together as one measure when we've lost out on who are these high achieving kids. How are they progressing? How many from different areas of this country and of different income levels are in those pockets? That is really, really important to continue to monitor.

Mike: Yeah, and frankly that is another fight at the state level. Right, I think that states can make decisions with their accountability systems. Like, to use strong growth models or use tests that can measure those higher levels of achievement in order to create incentives for schools to pay attention to those high achievers. But, that doesn't mean they're necessarily going to do that. So, it's on us again to make that case.

All right, that is all the time we've got for Pardon the Gadfly. Now, it is time for everybody's favorite part of the show, including Lisette's.

Lisette: I can't wait to meet Amber.

Mike: It’s Amber's Research Minute. Amber, welcome back to the show.

Amber: Thank you, Mike.

Mike: So, Lisette is number 1, a huge fan of yours and number 2, a huge Redskins fan.

Amber: Woohoo!

Lisette: Married one, so I might've become one by marriage.

Amber: We just had to let go of RG3. It was hard. Wasn't it?

Lisette: No.

Amber: But I think it was the right decision.

Lisette: No, it was not.

Amber: It was totally right.

Lisette: And that wasn't hard for you? I really liked the guy.

Amber: I really liked the guy too.

Lisette: Yeah.

Mike: It's like closing down a charter school. It's hard but some day you've just got to rip off the band-aid and start fresh.

Lisette: Right, right.

Amber: That last game Cousins just wow. Wow!

Lisette: It was ... I was there and it was so ...

Amber: You were there? We just kept turning around and singing the song. I was like, "Now, I finally know all the words!"

Lisette: All of us Redskins fans ... it only takes one game for us to go, "Oh baby, we're back on top."

Amber: We're back on bored.

Mike: Feel the love people, feel the love. All right, this is not the Redskins' podcast here.

Amber: All right, we're going to talk about the study. All right, it examines whether information is ... and this is kind of wonky and I'm going to do my best, but whether information supplied about a student's ability will help inform that students' decision to enroll in AP classes. Okay? So, you're basically giving them a little bit a little more information about their ability. All right, just stick with me.

All right, the information signal is the AP potential message. So when they take the PSAT results and they get ... Lisette's shaking her head. She knows this. When they get their results back, the college board will put a little message on there. The message will say you basically meet a certain cut-point that they determine. The message will either say, "Congratulations, you're score shows you have potential for success in at least one AP course!" Or you get the message that says, "Be sure to talk to your counselor about how to increase your preparedness." So, you either get one, or you get the other.

All right, so [inaudible 00:15:59] looked at students in Oakland Technical High School who took the PSAT in 2013 and the sample comprised roughly 500 sophomores in this big, huge school in Oakland. Okay?

Mike: Okay.

Amber: The intervention was as follows. Right before and after they received their PSAT results, that included one of these messages I just told you about, they were given a pre-post survey that asked them how they perceived their academic abilities and their plans relative to attending college, the number of courses they planned to take, whether they were going to take the SAT, and whether they think they're going to pass the high school exit exam and graduate from high school. So, what do you think about your future? Okay?

They're asking them this right before they get their results, in the classroom. Then right after they get their results. So, it's not a big window of time here, which is a little bit problematic. Analysts found that they AP signal ... So this message contained information that led students to revise their beliefs about their ability and future academic plans just in that short amount of time of receiving this message.

Specifically, they find that the PSAT is a negative information shock, which is the word they used. A negative information shock on average, meaning students tended to adjust down their beliefs about their ability once they got the news. So, specifically students who got good news, increased their beliefs about their ability by .187 points on a 5 point scale. Those who got the bad news revised their beliefs down by .286 points. I think they read the tea leaves relative to talk to your counselor.

Expectations around AP course enrollment were most impacted by the new information. So, all those 5 things I said they asked them about, the thing that was most susceptible to change was their AP course enrollment. So, students who'd upwardly revise their expectations, enrolled in more AP classes compared to students who didn't revise their expectations. Finally, they did this regression discontinuity design where they found that those that received the signal that you had the potential caused those students at the margin to enroll in approximately one more AP class the following semester and pass it.

Then, they were more likely to take and pass more AP exams. So, it would kind of have a domino effect. But the non-surveyed students at the margins did not show those patterns. Suggesting that filling out the survey actually increased the salience of the information. So, it's kind of like it really ... when students had to fill this thing out it became more real to them. But the students near the margin that didn't get that nice, fuzzy message were discouraged from actually taking the AP courses. Even though, they were nearly identical in ability to the other kids who got the other message.

So, the bottom line is, there's both an upside and a downside to this news based on whether you get good news or bad news.

Mike: So, one answer is don't give the bad news? They get the score report but don't have a message on there.

Amber: Yeah, that's right.

Mike: But what else? Certainly ... Look, this is part of the college board and other organization's efforts to try to use those PSAT scores to try to identify kids who could succeed in AP and let them know about it. So, that's all good.

Amber: It's all good.

Mike: We want to do that. Absolutely. It's tricky. Do we want to let those other kids know the sobering news. On the one hand, maybe you do, right?

Amber: Yeah.

Mike: This is stuff. We get in these issues with remedial education in high school, in higher ed. Are we doing young people a favor when we encourage them to give it a try, even though we have good evidence that they're going to fail? They're going to fail because they're just way too far behind. One thing, if we could help them catch up. But if we're just ...

Amber: Yeah, I know. Of course, the old teacher in me is thinking, "Oh, how sad." They just get this message and now they fill out the same survey and they just thought they were going to do all of these great things and now they're like, "Eh, maybe not." My life is taking a different course.

Lisette: The school that my program is housed in, Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, was actually noticed as one of the higher performing students on the recent park results. But in terms of advanced placement courses the school is really persistent around trying to make sure that students who took AP courses were the right fit for those courses and used the AP potential as a strong indicator as to whether they put students in those courses.

It's been really successful. I think it's been able to help students be successful.

Amber: Do you think the kids who didn't get that lovely message were discouraged or you think they went ahead and tried it anyway?

Lisette: I didn't even know about the message. So, I'd be curious now to see if there were students that paid attention to that.

Mike: And it's tricky, right? Some people would say, maybe Jay Matthews would say, "Oh, that's too much gate keeping." "We shouldn't be keeping those marginal kids out." On the other hand, if they're not going to be successful, if there's potential that they might slow down the other kids who really have the better shot at being successful. But it does sound like the school certainly is trying to be aggressive about telling young people who are ready, "Hey, we want you in these AP classes." It can't be just a letter home. The survey was one way to get people to focus on it.

It makes me think, Amber. I would love for us to do a study. I've always been curious about how parents are responding to these test score results, if at all and to do something similar. Survey parents, what do you think about ... How do you think your child is doing? How are they on track for college and career? Take the survey, then hand them the results from Park and then do the survey again. How do they respond when they ...

Amber: They're probably going to be like, "This test stinks."

Mike: That's probably what they will say. That will be ... I think so. I'd be curious, right? But the thing is, just the act of having to do the survey would be different from in the real world where I think a lot of parents are going to get these things in the mail, maybe not even open them or open them and be totally perplexed by what it is and just not worry about it or go ask their kid's teacher and the teacher will say, "Oh, don't worry about it. It's just the first year." I don't know that it's going to succeed to overcome their belief.

If they believe their kid's doing fine, and they should. Why wouldn't they? They've been getting reports from the school for 10 years if their kid's doing great. Why are they going to believe this piece of paper telling them that they're not?

Amber: Tell us what was a little bit problematic about how the study was designed, right? Because just the act of filling out the survey is almost nudging the kids to alter ...

Lisette: They're thinking.

Amber: Yeah.

Lisette: Am I supposed to feel bad about myself now?

Amber: So, it's a little bit problematic and I don't know how you get around that. It could've been that the intervention itself was what was skewing the results.

Mike: See, I know how you get around this Amber. It's easy. You track the kids on social media and you evaluate the emotional content of their messages before and after the news. Okay? Nobody will have any problems with that kind of research design would they?

Amber: Not at all. It's amazing what you could find out in a minute if that was done. And social media is so scary, right? I was looking for a chandelier for my dining room the other day and all of a sudden I get all of these chandelier ads on Facebook because I was on these other websites. Nothing to do with Facebook.

Mike: We're never leave you alone.

Amber: But it's scary. Anyway, I digress.

Mike: All right, I'm telling you social media, Amber, someday we're going to crack this. We're going to figure this out.

Amber: We ...

Mike: As a research tool. So much potential.

Amber: I think it's so important that we do continue to identify those students and tell them that they are capable of advanced placement courses. I think all too often, a busy single mom/dad at home sometimes may not even realize that their child has high potential.

Mike: Yeah.

Amber: If it weren't for that report telling that child, they may not know.

Lisette: Good point.

Mike: That is a great way to end. Okay, now Lisette you've been listening. You know how we end this show. Let's see if you get this right. We say, "That is all the time we have for this week's Education Gadfly Show. 'Till next week ...

Lisette: I'm Lisette Morris.

Mike: And I'm Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Very nicely done. Signing off.

Welders, as Marco Rubio recently reminded us, sometimes earn more than philosophers. But neither of them earn as much as students who receive degrees in STEM subjects. So perhaps the most encouraging bit of data to emerge from the ACT’s “The Condition of STEM 2015” report is this: Of the nearly two million high school graduates who took the ACT in 2015, 49 percent had an interest in STEM.

Interest, however, does not necessarily translate into aptitude. For the first time this year, ACT has added a new “STEM score” to their report—an acknowledgement of recent research indicating that college success in science, technology, engineering, and math classes requires a higher level of preparedness than ACT’s previous benchmarks in math and science alone seemed to predict.

Based on this enhanced measure, a paltry 20 percent of the 2015 ACT test takers were deemed ready for first-year STEM college courses. For reference, readiness is defined as either 1) a 50 percent chance of earning a B or higher or 2) a 75 percent chance of earning a C or higher in freshman courses like calculus, biology, chemistry, and physics. Among students who say that they are interested in STEM majors or careers, readiness jumps to 26 percent. (OK, "jumps" might be something of an overstatement.) And for those whose interests and activities, according to ACT’s “interest inventory,” indicate that STEM is for them, readiness climbs “all the way up” to 33 percent. None of which inspires confidence that the next Bill Gates or Steve Wozniak is acing freshman math as we speak (assuming they haven’t already dropped out and set up shop in the garage).

The report also surfaces a bit of a vicious circle: Nearly half of the class of 2015 might say they’re interested in STEM majors, but few plan to teach these subjects to tomorrow’s STEM-minded pupils. “Less than 1 percent of all ACT-tested graduates expressed an interest in teaching math or science,” the report notes. "Despite a larger number of ACT-tested and STEM-interested students this year, the number interested in teaching math and science was lower than in 2014.” Given their demonstrated lack of proficiency, this might not be all bad.

No word on how many want to become welders.

SOURCE: “The Condition of STEM 2015,” ACT, Inc. (2015).

A new Social Science Research study examines racial differences in how teachers perceive students’ overall literacy skills. It asks whether there are differences in these perceptions and to what extent they might be a reflection of a difference in actual abilities. In other words: Are teacher perceptions accurate?

The study uses data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, specifically those students enrolled in first grade during spring 2000 who had literacy test scores from kindergarten and first grade (ECLS-K administers a literacy test). Teachers were also asked to evaluate students’ overall ability relative to other first-grade students on a scale that ranges from “far below average” to “far above average.” The analyst controls for a host of student, teacher, and classroom variables in the regression analysis, including parental income and education, teacher race, percentage of poor students in the school, and more.

The study finds that, per the average performers, teachers were mostly accurate in labeling them so; there are no statistically significant racial differences in teacher ratings here. But among lower performers, teachers tend to rate minorities (Asian, non-white Latino, and black students) more positively than their performance suggests, while low-performing white students were rated more negatively than their performance would warrant. More specifically, minorities are 4–6 percent less likely than their similarly performing white peers to be rated “far below average.” Among the higher performers, the reverse is true—meaning whites are rated more positively and minorities more negatively. Specifically, high-performing minority students are between seven and nine percentage points less likely to be rated far above average.

The author—also a sociologist—posits that increased awareness of equity issues may compel teachers to use “restraint” in using labels such as “far below average” when referring to low-achieving minority students. (Or, she says, teachers could be harder on white students who are low-performing if they tend to have higher expectations of white students in general.)

The race-based discrepancies on the high end are quite concerning at a time when all high-achievers, including minorities, tend to get overlooked as teachers focus on their struggling students. But there are implications to this mindset, one of which the author closes with: “If the cognitive abilities of high achieving minority students hold less value in teachers’ overall perceptions, they may also hold less value during decisions concerning academic placements, access to enrichment opportunities, and the distribution of resources and support.” Needless to say, that’s a very big problem.

SOURCE: Yasmiyn Irizarry, “Selling students short: Racial differences in teachers’ evaluations of high, average, and low performing students,” Social Science Research, Vol. 52 (July 2015).

All right, first things first: What do we mean when we use the phrase “Response to Intervention” (RtI)? Its utterly functional label—surely all interventions are designed to provoke a response—lends itself to a host of vague interpretations. Education Week has produced a useful overview of its growth and effects, and Fordham attempted the same in its 2011 exploration of trends in special education, but the general points are these: RtI emerged around the turn of the century as a way to identify kids with learning disabilities as early as possible, provide them with a series of gradually intensifying academic interventions, and monitor their progress throughout. Spurred in its expansion by the 2004 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (which permitted districts to use up to 15 percent of their Part B dollars on early intervention services), RtI supplanted IQ-focused “ability/achievement discrepancy” models of learning disability screenings, and it eventually came to be adopted as a general education framework. In the words of Alexa Posny, the DOE’s assistant secretary of special education and rehabilitative services, the approach “hasn’t changed special education. It has changed education and will continue to do so. It is where we need to head in the future.”

This extremely thorough study, published by MRDC in partnership with the Institute of Education Sciences, sets out to examine both the prevalence and effects of schools providing RtI interventions for students at risk of reading failure in elementary school. It differs from earlier assessments of RtI in a few critical respects. For one thing, it casts a broad net, measuring its results at the school level (rather than the district level) in thirteen states. It also compares two separate groups: One, an impact sample of 146 schools, was picked from those that had three or more years of experience in implementing RtI approaches for reading; the second was a reference sample comprising one hundred randomly selected schools from the same states. Finally, the study uses a regression discontinuity design to estimate impacts. What this means is that it focused on students just on either side of their respective reading grade levels, rather than students more broadly. As the authors put it, the study “does not assess whether the RtI framework as a whole is effective in improving student outcomes or whether reading interventions are effective for students well below grade-level standards.” It is up to others, then, to determine the impact of the method on the children who are furthest behind.

The results show that some 70 percent of districts in the thirteen states reported offering RtI services. No surprise there—the method has spread widely since the passage of No Child Left Behind and the 2004 IDEA update; the same figure was measured at 61 percent in 2010. Impact sample schools were more likely (97 percent versus 80 percent) to provide interventions like small group instruction for students somewhat below grade level at least three times per week; they were also more likely (67 percent versus 47 percent) to provide such interventions for students significantly below grade level at least five times per week. Schools in the impact sample were far more likely to conduct universal screening of students at least twice per year, and also to allocate extra staff to assist in reading instruction and data usage.

Most surprising by far are the results for RtI effectiveness. The study actually ascribes a negative effect to such interventions in the first grade—that is, for students either somewhat or significantly below grade-level reading, being engaged with RtI services like extra instructional time actually lowered their scores on assessments of both comprehensive reading and fluency decoding. Few could have anticipated such an outcome. Still, given the ubiquity of RtI and the acknowledged limitations of the study, more information is needed before drawing wider conclusions on the efficacy of the approach.

SOURCE: Rekha Balu et al., “Evaluation of Response to Intervention Practices for Elementary School Reading,” U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics (November 2015).