Differentiated to death

It’s the Holy Grail! If only we could figure out what it is. David Griffith

It’s the Holy Grail! If only we could figure out what it is. David Griffith

Imagine you are a first-year social studies teacher in a low-performing urban high school. You are hired on Thursday and expected to teach three different courses starting Monday. For the first two weeks, you barely eat or sleep, and you lose fifteen pounds you didn’t know were yours to lose. For the first two months, your every waking minute is consumed by lesson prep and the intense anxiety associated with trying to manage students whose conception of “school” is foreign to you. But you survive the first semester (as many have done) because you have to and because these kids depend on you. You think you are through the worst of it. You begin to believe that you can do this. Then, the second semester begins…

Your sixth-period class is a nightmare, full of students with behavior problems that would challenge any teacher. But as hard as sixth period is, your third-period class is the most frustrating and depressing, because (for reasons only they are privy to) the Powers That Be have seen fit to place every type of student imaginable into the same classroom: seniors, juniors, sophomores, freshmen, kids with behavior issues, kids with attention issues, kids with senioritis, kids who have taken the class before and passed it but are taking it again because the registrar’s office is incompetent. And, of course, a few kind, sweet, innocent kids. Who. Cannot. Read.

This is impossible.

Or so you tell the Powers That Be. Your seniors can do the worksheets you assign them in twenty minutes, or roughly the time it takes your slower kids to write their names. Your high flyers already know who the Romans and the Greeks were, but the rest of the class is lost. How can you possibly teach all these kids at the same time?

Differentiate your instruction, young man.

Or so say the Powers That Be, who play the education game far better than you. So you try.

Hello! Rocketship Education? Can you send me thirty-one laptops with the latest research-based adaptive learning programs?

No dice.

Hi there! Ms. Granger? Would you mind lending me your Time-Turner so I can teach each of my classes thirty-one times and make sure each of my students gets the lesson he or she would most benefit from receiving? HUGE fan of yours, by the way, Ms. Granger.

Differentiation. The solution to all problems. The Holy Grail of effective practice! What is it, exactly? Mixed group work? Harder worksheets for the more advanced kids? Optional diorama projects? All of the above?

According to Carol Tomlinson, differentiated instruction is “an approach to teaching that advocates active planning for student differences in classrooms.” But what differences? Any differences? All differences?

No matter. Regardless of what it means to differentiate, doing so has clear benefits, say the Powers That Be:

Then again, perhaps you have misunderstood somehow. Perhaps differentiation is really just a fancy way of saying that you should know your students and try to design interesting lessons that meet them halfway. Which is arguably just a roundabout way of saying you should be a good teacher. Which, coming from the Powers That Be, is really just a slightly devious and politically correct way of saying you should just deal with it already, OK?

But if that’s all it means to differentiate, shouldn’t someone say so? After all, it would be one thing if there were research showing that different children really do have different learning styles. Or that struggling readers benefit from being given easier reading assignments than their more advanced peers. Or that stone-faced teachers have historically made a habit of ignoring their students’ individual needs and quirks.

But since no such research actually exists, perhaps you would be better off just teaching the best lesson you can to as many kids as you can coerce coax into paying attention. Perhaps, instead of flirting with multiple-personality disorder by attempting to be all things to all children, you should do what seems sensible and reasonable under the circumstances. Perhaps you should do what works for you, since anything that doesn’t is highly unlikely to work for the kids. And perhaps you’d have a fighting chance of actually finding something that works if the Powers that Be, or the parents they so cunningly placate, made some minimal effort to differentiate kids before they entered the classroom.

The author was unceremoniously laid off after his first year of teaching. He now plays the role of education gadfly, a far easier task than teaching well.

Almost every article and column written about the nascent GOP presidential campaign mentions Tea Party opposition to immigration reform and the Common Core—and most candidates’ efforts to align themselves with the Republican base on these two issues. (A Google News search turns up more than 11,000 hits for “Common Core” and “immigration” and “Republican.”)

When it comes to immigration reform, it’s easy to understand what the hard-right candidates oppose: any form of amnesty for people who entered the country illegally.

But what does it mean when Ted Cruz, or Rand Paul, or Bobby Jindal says he “opposes” the Common Core? Reporters* might ask them:

* These are good questions to ask Republican senators, too, who will almost surely rail against the Common Core when the Elementary and Secondary Education act comes to the Senate floor later this year.

Obama’s budget, a bad book about testing, differentiation difficulties, and the high cost of empty buildings.Institute for Law & Liberty (January 2015).

SOURCE: Rick Esenberg, CJ Szafir, and Martin F. Lueken, Ph.D., "Kids in Crisis, Cobwebs in Classrooms," Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty (January 2015).

Aylssa: Hello, this is your host Alyssa Schwenk of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, here at the Education Gadfly Show and Online at edexcellence.net. Now, please join me in welcoming my co-host, the right shark of educational reform, Robert Pondiscio.

Robert: How nice.

Aylssa: Thank you.

Robert: Can I be the Marshawn Lynch of education reform?

Aylssa: I think as long as you're not the Pete Carroll of education reform, you're in good standing.

Robert: I just want to say that I'm only here so I don't get fined.

Aylssa: Not to dance at all?

Robert: Not to dance, and not to call a bad play in the line of scrimmage. Let's hope.

Aylssa: I actually cannot follow this part of the conversation because I was one of those people watching the Super Bowl exclusively for the half-time show-

Robert: Right.

Aylssa: And the commercials, but I do know that that was a bad call.

Robert: Okay. The football game, that's the part that wasn't the commercials or the half-time show. With the guys in the helmets, that was-

Aylssa: You mean when I went to go get food?

Robert: Exactly.

Aylssa: Okay.

Robert: Right.

Aylssa: All right. Moving on to education reform let's hop right into Pardon the Gadfly. Ellen, what's our first question today?

Ellen: President Obama's budget was released this week and has been heavily panned by Republicans. Is it worth analyzing or is it just a bargaining chip?

Aylssa: All right. President Obama on Monday released the first on-time budget of his administration, always an accomplishment. It had about $71 billion, slightly less than that, dedicated to education funding. It was a pie in the sky list of every initiative that he and Arne Duncan really want to get across in the next year or in the last two years of their administration. It included $750 million for pre-K funding, increases in charter school funding, increases in formula funding, but a lot of people are saying that it's just a political maneuver. Robert, what are your thoughts?

Robert: A budget is by definition a political maneuver, is it not? It's a wish list.

Aylssa: That is true. You measure what you treasure.

Robert: Very nicely put.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Is that original?

Aylssa: I think it is actually ... No.

Robert: I like it.

Aylssa: Thank you.

Robert: I would refer people to Andy Smarick's post on this-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: That he put up on our blog earlier this week. Andy is a veteran political observer-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: And he makes exactly that point. It's a political document. He points out that the chickens have come home to roost, that some of these incentive-based grant programs-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: That used to be very popular are suddenly unpopular. He also points out that the things you would expect to be popular with Congress will remain so-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: It's Title 1-

Aylssa: Title 1.

Robert: Funding and what not.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Mike Petrilli, our other Fordham colleague, says basically what you said, "Dead on arrival. Why are we even talking about this."

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, I do think I agree that it is dead on arrival. I think it is a fairly ambitious list and we've also seen a more muscular ready-to-fight president than we've seen in the last couple of years. The State of the Union was almost cocky and very, very aggressive in some ways.

Robert: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Aylssa: Some might say confident, some might say aggressive. I do think that this budget is in a way kind of is a harbinger. Harbinger?

Robert: A harbinger? A harbinger.

Aylssa: A harbinger of what might be a more aggressive fight than people are expecting.

Robert: It's easy to say that when you have both houses of Congress on your side which, of course, the President, remind me-

Aylssa: That is.

Robert: Does-

Aylssa: Does ... Not.

Robert: Does ... Not. Right? Okay.

Aylssa: No, he doesn't.

Robert: Again, why are we talking about this?

Aylssa: Fair point. Question 2?

Ellen: Robert, this week you penned a negative review of a new book on testing by Anya Kamenetz. Will you elaborate?

Robert: Do I have to? I don't know Ms. Kamenetz. I listen to her reports on National Public Radio. She seems like a good and diligent and dutiful education reporter. Here's the thing, okay. I wanted so much to love this book. I have slightly unorthodox views about testing for somebody who is in the ed reform community. As a former teacher, I would say my relationship with testing is complicated. The problem is Anya Kamenetz's take on testing is kind of uncomplicated. She just really doesn't like it and she makes that clear right from the very, very-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Start. I was disposed to find things to agree with because, again, I have this relationship that testing, like she would say, "The testing has become the tail that wags the dog," but she's just in spots so stridently anti-testing that I'm finding myself hard-pressed to agree with very much in the book at all. One piece in particular that really raised my hackles is she raises the idea that testing almost by birth from its historical roots a century ago, there was something intrinsically racist, my words not hers, about standardized testing, but it completely overlooks the fact that testing has really done a lot for the cause-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Of equity in our-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Country. In fact, a week or so ago, there was a letter penned by some 19 or 20 different civil rights groups who are basically among the most stalwart proponents of testing-

Aylssa: Yeah.

Robert: But Ms. Kamenetz does not seem to be down with that argument.

Aylssa: Yeah. It's kind of an unpopular view as a former teacher to take, but I liked testing or rather I liked assessment. I think the purposes and the value in it are frequently overlooked. It's something to keep your students on track. It's something that, as the civil rights leaders pointed out in their letters, to ensure that equity is being met, that students are making progress. It completely-

Robert: Sure.

Aylssa: Reshapes the landscape of schools since the 1960s forward. Has it created some perverse incentives? Yes. Has it at some schools, the one that I taught at was a very high-stress environment, particularly-

Robert: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Aylssa: Around testing time. Yes, absolutely. Those things need to be rectified. I do feel that there is value in testing, that this book, I haven't read it-

Robert: Sure. Yeah.

Aylssa: But it does apparently overlook.

Robert: How could there not be.

Aylssa: Right.

Robert: None of us want to go to the battle days before-

Aylssa: Right.

Robert: We knew who was struggling and why. Another frustration with this book, at the end, she's all but advising parents to opt out of testing-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: I just wish somebody would go about this the following way. Rather than just say, "No more testing, we're not gonna do it," because look-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Parents are absolutely right to be concerned that there is too much testing. I would love to see some savvy group of parents go to a school and say, "Okay, Mr. Principal, Ms. Principal, here's the deal. We're inclined to opt out but we're going to give you a chance first.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Keep the test prep away, the books away. No more practice tests. The second you turn schooling into test prep, our kids are going to opt out, so you teach, our kids will come for the test."

Aylssa: You think that'll be effective?

Robert: I do think it would be more effective because it would give parents what they want, a rich educational-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Experience. Would let teachers do what they want, to teach the-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Curriculum, not to the test. The irony, of course, would be if that happens and then the test scores come back looking poorly. Then, it'll be interesting to see if opt-out parents are as aggressive about wanting to opt out as they are now.

Aylssa: That would be a fair point. I do think that looking ahead I know her daughter is quite young-

Robert: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Aylssa: And that was the genesis of writing this book. I often wonder will these parents opt out of the SAT when suddenly it has very steep consequences for their child.

Robert: Testing been very, very good to those-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Of us who went to fine colleges, right?

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Amen. All right. Question 3.

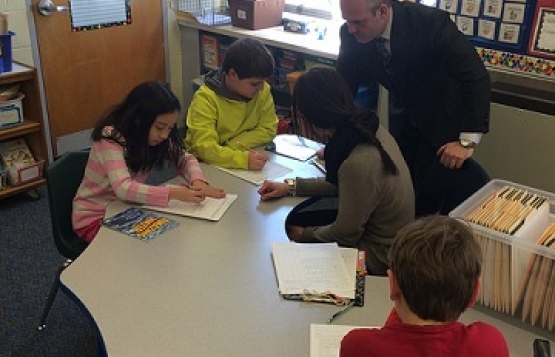

Ellen: Fordham colleague, David Griffith, recently wrote about his disastrous experience with differentiated instruction. You two were teachers, what do you think of this method?

Robert: What do you think of it?

Aylssa: My question back at you is what is differentiation?

Robert: Great question.

Aylssa: David, I think in his piece, which is out in today's Gadfly, addresses that paradox of, how do we define differentiation? It's like the elephant that six blind men are feeling, and sometimes it's a tree trunk, and sometimes it's a rope, but what is it actually?

Robert: Yes.

Aylssa: I have my own definition as a former teacher, and you're still teaching, Robert. What's your definition?

Robert: First of all, I think differentiation is one of those things that more honored in the breach than the observance. Everybody talks about it, but very few people actually do it. You're exactly right.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: In order to say do you like it, do you like it. The first question is what do you mean by differentiation.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative). You know when you see it.

Robert: Yeah, you know when you see it ... Or when you do it. In other words, for me, what does differentiation look like in my classroom. It means when I read two different student's papers, I'm looking for different things based on-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: How I think I can add value to them in terms of the feedback. If that's what you mean by differentiation, fine. If it means, I'm going to ask a different question of different kids in classroom discussion based on what I perceive to be their level of readiness-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: That's okay. If it means 24 kids doing 24 different things? No. That's a recipe for just frustration.

Aylssa: I'm curious. I taught kindergarten and second grade, and my experiences is with differentiation and how it was perceived were very different with those two grade levels. When I was teaching kindergarten teaching small group or instructing in small groups, was considered geno-appropriate. People would come in and be, why are these kids working on this lesson and these kids working on this. I would be, it's developmentally appropriate. There's no such thing as silent or passive disengagement-

Robert: Right.

Aylssa: From a 5-year-old if they're not liking the lesson.

Robert: They let you know.

Aylssa: They're doing somersaults-

Robert: Yeah.

Aylssa: Quite literally doing somersaults, but I recognize that it's much different with older students.

Robert: Sure.

Aylssa: Are you when you're teaching high schoolers breaking out into small groups? Is that differentiation to you?

Robert: Very, very rarely-

Aylssa: Okay.

Robert: I think it just doesn't work at the high school level. One other thing about differentiation that I think is worth noting. People have very strong opinions about this.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: People will say, "Well, there's no evidence that it works, but, you know, there's no evidence that it doesn't." The thing that always occurs to me is that, look, we've got 3.7 million teachers-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: In this country with a range of effectiveness and proficiency. If the literature is mixed and we're not sure that these are effective-

Aylssa: Right.

Robert: Strategies, why are we needlessly complicating the job?

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: I bang on this drum mercilessly, but we've got to make teaching a job that mere mortals of average sentience can do, to a fairly high degree of proficiency.

Aylssa: That's a ringing endorsement.

Robert: I don't mean to be arch or ironic-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: At all when I say that. The job is hard enough. Why would you go and jump through hoops to make it immensely difficult if you're not absolutely sure there's benefits.

Aylssa: That's true. I do think at the end of the day, teachers need to do what works best for them and their classroom and their kids, in conjunction with the administration, in conjunction with parents when appropriate. If it works for them, great, at what they're doing. They need to be doing something, I feel like they should be allowed to do that too.

Robert: Amen.

Aylssa: All right. I think that's all of the time that we have today for Pardon the Gadfly. Thanks so much, Ellen. Next up, Amber's Research Minute. Welcome to the show, Amber. How are you?

Amber: Thank you, Aylssa, doing great.

Aylssa: All right.

Amber: Doing well.

Aylssa: Earlier today, Robert was running touchdown dances around me with his football knowledge. I was watching the Super Bowl on Sunday night for Katy Perry and Left Shark and Right Shark-

Amber: Oh. Right.

Aylssa: And the commercials. Robert was, I don't know why you were watching it. You were trying to explain it to me, but it involves-

Robert: Something about a football game.

Aylssa: Touchdowns.

Robert: Yes.

Aylssa: Okay.

Robert: It involved touchdowns.

Amber: Great game.

Robert: It really was, right?

Amber: It was a great game.

Aylssa: You we're watching?

Robert: Yeah.

Amber: Of course. That was just a terrible play. I was rooting for the Sea Hawks, just very, very depressed at that last play. Come on, what's he thinking that coach?

Aylssa: Why he throw it?

Amber: Why he throw it?

Aylssa: All right.

Amber: I'm preaching to the choir. Everybody knows this.

Aylssa: Well, I was rooting for the Sea Hawks. I'm not sure you're-

Robert: I was rooting for the Patriots. I have to say I-

Aylssa: I was going to say you're from [inaudible 00:11:34] Northeast Corridor.

Robert: I'm a Buffalo Bills fan, so the Patriots are in our division.

Aylssa: I guess that's a good enough reason. I'm clearly not remotely qualified to judge. Amber, what do you have for us today?

Amber: Let's switch gears and talk about a new study by the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty. We don't cover a lot of their stuff, but this was a neat little study. They examined the facility challenge in Milwaukie. Basically the story in Milwaukie is you've got abundance of choice, both in charters and private school choice. Families are leaving these district for the charter and private schools, and they basically looked at the utilization rates, so how utilized are each of the public school buildings in Milwaukie. All right. Five quick findings. Number 1, there are 27 buildings that are operating at below 60% capacity.

Robert: Hmm.

Amber: Of these, 13 are operating below 50% capacity. Many of these schools are the most at risk schools in the city. They have declining enrollments, they're the lowest performing, yaddie-yadda. They have twice as many 911 phone calls per student, which I thought was interesting little factoid.

Aylssa: That's a heartening finding.

Amber: Yes. Higher absentee rate than other public schools. Number 2, there are currently, and this blows my mind. There are currently 17 Milwaukie public school buildings that are completely vacant, and they have been for an average of guess how many years.

Robert: 5 years.

Aylssa: 2.

Amber: 7. 7 years.

Robert: Out of-

Aylssa: [inaudible 00:12:59].

Robert: Good. Out of many buildings?

Amber: 7 years. Let me see if I had wrote that done. It cost the taxpayers about 1.6 million in utilities-

Robert: Wait a minute-

Amber: Just in utilities.

Robert: 1.6 million to keep-

Amber: Since 2012.

Robert: 7 buildings.

Amber: 17.

Robert: 17. Sorry.

Amber: 17.

Robert: Open.

Amber: Right.

Robert: Empty.

Aylssa: For 7 years.

Robert: Wow.

Amber: For 7 years, just utilities. Who knows what other costs we're talking about. Number 3, 80% of the under-utilized schools, 22 in total, received either an F or D on their most recent state report cards. Again, just reiterating these are low performing schools that are under-utilized.

Robert: How did the empty ones do?

Amber: Under-utilized schools are more likely to experience enrollment decline. That's circular logic but that's true.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Amber: The concern is that they're eventually going to be vacant. These kids are just going to keep leaving. Number 5, last one, is severe shortage of quality public schools exist in the vicinity of the under-utilized schools, so that makes sense, right? Out of 52 closest schools of those schools that are under-utilized, only 7 scored a C or better. They're surrounded by-

Robert: Mediocrity.

Amber: Yes.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: At best.

Amber: So the authors, obviously, no surprise, they recommend that private schools, the choice program, the charter schools and-

Robert: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Amber: Be allowed to expand into these unused and under-utilized buildings. They said they could either take over the buildings-

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Amber: If they're high performing charter. They can lease out the space. They can consolidate the MPS schools and lease the leftover part of the building.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Umm.

Amber: There's all different kinds of options here, is the point.

Aylssa: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Right.

Robert: Yeah.

Amber: All of which-

Robert: They can't do that now, I assume-

Aylssa: Yeah. What's stopping them?

Amber: The district is not real keen on-

Robert: They're not playing ball.

Aylssa: [crosstalk 00:14:35] do any of this stuff.

Robert: Yeah.

Amber: Mm-hmm (affirmative). For reasons that we probably know.

Robert: Sure.

Amber: So the taxpayers are getting sucked to them.

Robert: Yeah.

Amber: Yeah. Milwaukie public officials are doing nothing. The author's saying can the state actually do something about this problem?

Robert: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Aylssa: That's fascinating. I know I taught in D.C. and obviously the co, what do they call it?

Robert: Co-locations. It's a big problem in New York.

Aylssa: Co-locations, in New York is a big problem as well.

Robert: Yeah.

Aylssa: In D.C., it's very expensive just because of legislation for charter schools to take over public school buildings.

Robert: Right. So this-

Aylssa: I think it's gotten easier but that's not even what's happening here.

Robert: This isn't even co-location.

Amber: Right.

Robert: This is empty real estate that somebody could putting to good use.

Amber: Empty real estate. Yeah, and they're just putting up a road block.

Robert: Wow.

Amber: They're not playing nicely.

Robert: No bueno.

Amber: In D.C., they have Building Hope.

Aylssa: Right.

Amber: Which is an organization that helps to fund some of these charter facilities, help them finance them. There's no organization like that in Milwaukie, which they desperately need.

Aylssa: Yeah.

Robert: Right. So this report is basically try to stir up some outrage to say-

Amber: Kicking up some dust-

Aylssa: That's a terrible problem and I hope it's able to stir up some necessary outrage to get the ball rolling there.

Amber: Yes. We like to create outrage around here.

Robert: I don't know what you're talking about.

Aylssa: They don't call us the Education Gadfly for nothing.

Amber: That's right.

Aylssa: All right. That's all of the time that we have for this week's Gadfly Show until next week.

Robert: I'm Robert Pondiscio.

Aylssa: And I'm Aylssa Schwenk for The Thomas B. Fordham Institute signing off.

Speaker 1: The Education Gadfly Show is a production of The Thomas B. Fordham Institute located in Washington D.C. For more information, visit us online at edexcellence.net.

No one disputes that great teachers are essential. But how do we get more of them—do we find them or make them? In this book, an elaboration of her New York Times Magazine cover story, Chalkbeat’s Elizabeth Green roundly refutes the narrative that the teaching ability is like a “gene,” contending instead that teaching skills can be taught. The author retraces the history of pedagogical research—from education psychologist Nate Gage through math pedagogy expert Deborah Ball—to illustrate the institutional resistance to instruction-centered reforms. Though scholars, policy makers, and educators are obsessed with quality teaching, the myth of the teaching gene silences efforts to study and improve teachers’ techniques. New instructors, working in isolation, continually reinvent the wheel, with little success. But perhaps that’s starting to change. Some researchers are beginning to systematically observe and record teachers’ methods, allowing successful approaches to emerge. (For instance: Lemov’s taxonomy and Ball’s “This Kind of Teaching.”) This book bears good news for the American education community: if effective pedagogy can be learned, we needn’t wait for great teachers to come to the profession—we can start improving the ones we have.

SOURCE: Elizabeth Green, Building a Better Teacher: How Teaching Works (and How to Teach It to Everyone) (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, July 2014).

Education governance puts most people to sleep. The topic is arcane, sort of boring and, above all, seemingly immutable. If you can’t do anything about a problem, why agonize over it, or even spend time on it?

Of course, some people don’t even see it as a problem. They just take it for granted, like the air surrounding them, the sun rising in the morning, and the Mississippi flowing south. It just is what it is.

That’s wrong-headed. The governance mess is a large part of the reason that so many education problems are impossible to solve. As Mike Petrilli and I wrote three years ago about “our flawed, archaic, and inefficient system for organizing and operating public schools”:

[America’s] approach to school management is a confused and tangled web, involving the federal government, the states, and local school districts—each with ill-defined responsibilities and often conflicting interests. As a result, over the past fifty years, obsolescence, clumsiness, and misalignment have come to define the governance of public education. This development is not anyone’s fault, per se: It is simply what happens when opportunities and needs change, but structures don’t. The system of schooling we have today is the legacy of the nineteenth century—and hopelessly outmoded in the twenty-first.

Perhaps the foremost failing of that system is its fragmented and multi-polar decision making; too many cooks in the education kitchen and nobody really in charge. We bow to the mantra of “local control” yet in fact nearly every major decision affecting the education of our children is shaped (and mis-shaped) by at least four separate levels of governance: Washington, the state capitol, the local district, and the individual school building itself. And that’s without even considering intermediate units (such as the regional education-service centers seen in Texas, New York, Ohio and elsewhere), the courts (which exert enormous influence on our schools), or parents and guardians, and the degree to which all of their decisions influence the nature and quality of a child’s schooling.

At Fordham, we’ve done our best to call attention to the governance problem and suggest possible solutions, but we’ve never had a comprehensive answer to the legitimate question, “If you don’t like the current governance arrangement, what exactly would you do instead if you could?”

Now riding in from the far northwest with a coherent and compelling alternative are Paul Hill and Ashley Jochim, whose new book, A Democratic Constitution for Public Education, is timely, elegant, and systematic.

Their central insight is that education governance needs a proper constitution, much as the American colonies did, and that it’s time to replace a messy, failed, de facto arrangement with a clear sorting-out of duties, powers, limits—and checks and balances.

Their main focus is at the community level, where they preserve and revitalize the concept of local control while both freeing educators to do their best and holding them to account for their results. One might say they get “tight-loose” right. School boards as we know them are replaced by locally elected “Civic Education Councils” with clearly delineated responsibilities (and limits), and the “central office” as we know it is replaced by a CEO arrangement that oversees but does not run a network of more or less autonomous schools. In fact, schools get a “bill of rights” so that their autonomy doesn’t gradually get sapped by an overweening CEO or meddlesome council.

Hill and Jochim also take pains to recast both state and federal roles. Following the principle that everyone should be accountable to someone, the state’s main job, besides setting standards and learning objectives, is to monitor the performance of the local councils and intervene (or replace them or take schools away from them) when they mess up. (States, having sovereign constitutional responsibility for education, are accountable to their citizens and voters, not to Uncle Sam.)

As for the feds, the Department of Education becomes “a provider of ideas, examples, data, and research, not a prescriptive national ministry.” Regulation-heavy categorical programs are replaced by “backpack” funding of needy kids whose education costs Washington helps to bear.

The whole arrangement is designed to meet five criteria that the authors deem essential for a viable K–12 governance system. It must be “efficient, equitable, transparent, accountable and democratic.”

What about feasible? They’re not naïve. They understand that changing education governance is a “long, bumpy road” and don’t expect it to happen in one fell swoop. They usefully point to partial examples of these kinds of changes already being made in various parts of the country. They cite the reworking of school governance in half a dozen cities (e.g., New York) the emergence of a couple of “recovery” districts, portfolio districts, and a bit more. The authors do a swell job of describing obstacles, possible transition stages, and ways that the new arrangement, once enacted, could backslide (as some would say the U.S. Constitution has done!). It has to be said that one doesn’t end the book with a high level of confidence that Hill and Jochim’s “democratic constitution” can be put into place and sustained. But one ends it thoroughly persuaded that it should be. So please awaken from the governance slumber and read it!

SOURCE: Paul T. Hill and Ashley E. Jochim, A Democratic Constitution for Public Education (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014).

I’m no testing hawk. I’ve written plenty at Fordham and elsewhere that’s critical of test-driven ed-reform orthodoxy. Accountability is a sacred principal to me, but testing? It’s complicated—as a science, a policy, and a reform lever. Anya Kamenetz’s new book The Test is not complicated. She strikes a strident anti-testing tone right from the start. “Tests are stunting children’s spirits, adding stress to family life, demoralizing teachers, undermining schools, paralyzing the education debate, and gutting our country’s future competitiveness,” writes Kamenetz, an education reporter for National Public Radio. If you’re looking for the good, the bad, and the ugly on testing, well, two out of three ain’t bad.

Part cri de couer, part parenting manual (she may hate testing, but Kamenetz still wants her daughter—and your kids—to do well) The Test is particularly tendentious on the history of standardized tests. “Why so many racists in psychometrics?” she asks (her prose is often glib and always self-assured). “I’m not saying anyone involved in testing today is, de facto, racist. But it’s hard to ignore the shadow of history.”

What is easy for Kamenetz to ignore almost entirely is that some of the strongest support for testing comes from civil rights activists who have used test scores to dramatically alter the education landscape and highlight achievement gaps, all in the name of equality. But this runs counter to her argument that testing “penalizes diversity.” Kati Haycock may have once led affirmative-action programs for the University of California system, but her Education Trust is a “conservative-funded advocacy group in DC.” The Heritage Foundation’s Samuel Casey Carter offers “a mishmash of anecdotal evidence and conservative faith,” yet The Test is larded with Kamenetz’s own mishmash of anecdotal evidence and liberal homilies. A story from her own mother-in-law about a culturally biased test question is “possibly apocryphal,” Kamenetz admits. But she still offers it as “a great illustration of what bias looks like on a test.”

Kamenetz offers lots of advice on opting out of tests for parents who are, I think, quite reasonably concerned about the deleterious effect of testing on their children’s schooling. Here’s the advice I wish she’d offered: March into the principal’s office with a simple demand. “Don’t waste a minute on test prep. Just teach our kids. The second you turn learning time into test prep, our kids are staying home!” Imagine if Kamenetz and her fellow progressive Brooklyn public school parents did exactly that—teachers and parents could have the hands-on, play-based, child-centered schools of their dreams, and test day would be just another day at school. Unless, of course, the test scores came back weak. Then Kamenetz might write another, more complicated book. And that’s the one I want to read.

SOURCE: Anya Kamenetz, The Test: Why Our Schools are Obsessed with Standardized Testing–But You Don’t Have to Be (New York: PublicAffairs, 2015).

How do we get new and better private schools of choice? That’s the question AEI’s Michael McShane and a cadre of researchers and practitioners dive into in this new edited volume. The book and a corresponding conference acknowledge that “better is not good enough.” Indeed, for far too long, supporters of school choice have been content with merely providing alternatives to district school options on the assumption that choice was a sufficient guarantor of quality. Instead, this book calls for a “nimble, agile, and market-driven” system of schools. Among the high points is Andy Smarick’s look at what has worked in chartering: incubation (leadership pipelines, start-up capital, strategic support, and political advocacy) and network building. He also reprises his call for “authorizers” to oversee publicly funded private schools. McShane agrees that this model could “provide oversight without stifling the set of options available for school choice.” Perhaps. But private schools, from Catholic schools to those providing alternative curriculum, often see themselves as working toward ends that are more than academic. Could they maintain their distinctive flavor in a marketplace that could devalue their mission? New and Better Schools is a smart look forward in private school choice programs and a thoughtful critique of how and where these programs have not thrived.

SOURCE: Michael Q. McShane, New and Better Schools: The Supply Side of School Choice (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).